I fell backwards into dramaturgy. I was an intern for Young Jean Lee on Lear, though she gave me the title “Assistant Director” – a rather meaningful act of care. Through Lear I met choreographer Dean Moss. It was a time in downtown NY theater when every play had a dance break. I worked with Dean to help the actors to realize a minor dance in Lee’s otherwise epic adaptation of Shakespeare’s story of losing your/the father. From there Dean began inviting me into his rehearsals as a dramaturg. Simultaneously, I wrote an essay on Neil Greenberg, Jeremy Wade, and Jack Ferver while at NYU starting my PhD. Jack and I became friends and, knowing that I was interested in getting back on stage, he told me Ishmael Houston-Jones was preparing for a revival of Them. I signed up to audition and told my advisor, José Muñoz, who, much to my surprise, offered disapprovingly that research, not rehearsals, would have to be my priority as a PhD candidate. I withdrew from the audition and took Jack up on his invitation to be his dramaturg on Rumble Ghost.

That was almost fifteen years ago and since then, I have fallen in with dance dramaturgy, and with the philosophical questions dance dramaturgy asks one to consider: How close can one get to an artistic process without being one of its agents? Who is the work’s author and what does authorship mean? How does one navigate the intimacy of collaboration and what does it teach us about power and control? Am I part of the work or apart from it knowing that, as the dramaturg, I will always have arrived late and left early from the process? In short, no matter what the credits say, the dramaturg’s work remains invisible. Dancing at this threshold is the closest thing I have to an artistic practice – not because it takes creativity, but because it requires me to constantly face the unknown.

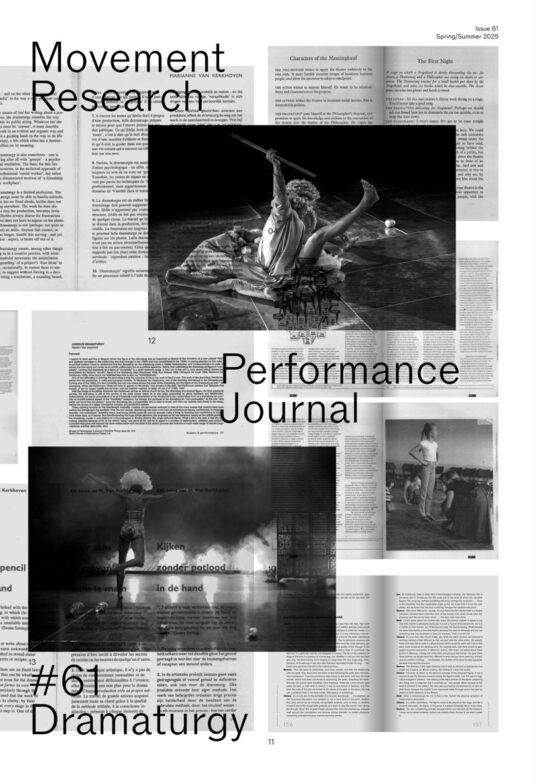

Theories of dance dramaturgy can be found in a growing body of literature on the field (see the cover of this issue). But for Issue #61 of the Movement Research Performance Journal the editors decided stay in the not-knowing by inviting contributions from those whose work touches on dance dramaturgy with curiosity, anxiety, anarchy, as well as a conviction for the intimacy it requires and a resistance to its history of institutional/state authority. At the heart of the issue is a special section by Contributing Editor Ligia Lewis. Across Lewis’ works there are not only a range of dramaturgs, but the role of dramaturgy shifts and morphs across projects and over time. The reinvention of the dramaturg that Lewis’ work articulates is something that has proliferated throughout the field of contemporary dance. The rest of the issue includes a range of texts, some from practicing dramaturgs, others from those who have reluctantly accepted this title, and still more who reject the role outright, all exploring a simple question: why has there been an explosion of interest in dramaturgs in contemporary dance? The explosion I’m thinking of is not about a growing professionalization of dance dramaturgy (though that is certainly happening). I mean simply that more dance and performance artists are including dramaturgs as part of their process, and at the same time seem to be continually reinventing what the dramaturg is meant to do. What can we make of the desire for the dramaturg as well as the desire to continually reinvent this figure and its function?

Issue #61 doesn’t answer these questions, but it does find concert with questions I hear echoing across the field, one that I think expresses a certain urgent need to invent new ways of working together. This urgency without resolve is partly what fueled a series of gatherings André Lepecki and I have hosted, called “Dramaturgy Support Group.” By way of concluding, I offer a short excerpt from one of these meetings.

– Joshua Lubin-Levy