Maia Sauer: I have been thinking about collage. I’m learning that leading a creative life requires tending to a shifting patchwork of jobs and interests and relationships, and this patchwork necessarily feeds into what I want to make and how I move my body.

Charline Davis-Alicea: Okay, this is something I’ve been thinking about a lot. I’m thinking about how it feels like we’re in a time where we recognize that we can’t create anything in a vacuum.

I think what we can bring to the table is a new way to orient, or relate, our unique set of influences. That’s where collage, mosaic, patchwork comes in. It feels like a good way to describe where we’re at. I don’t know who “we” are, but I think that it feels fitting to embrace the patchwork right now.

MS: Collage feels really linked to the internet to me. I’ve been thinking about this in “Lullaby Machine,” a piece I produced a draft of in May with five friends. Living online, in such close proximity to the digital-verse, informs that patchwork way of seeing the world and seeing myself in relation to my peers. It’s impossible to ignore a collage-like way of relating to each other.

We explored the bizarre comfort of certain spaces online, and how quickly that comfort of scrolling turns to chaos and fragmentation of self and relationships. We created a live collage, with my friend Sylvia Ke live-coding visuals that included snippets of different videos from YouTube’s first few years. These wacky ASMR videos, Zendaya’s first YouTube video, Emma Chamberlain’s first vlog, and all of these images. There was a Lo Fi Beats video in there. Each performer worked with different scores. One duet explored the performative nature of relationships online, this desire to be seen by an audience and also a genuine yearning for connection.

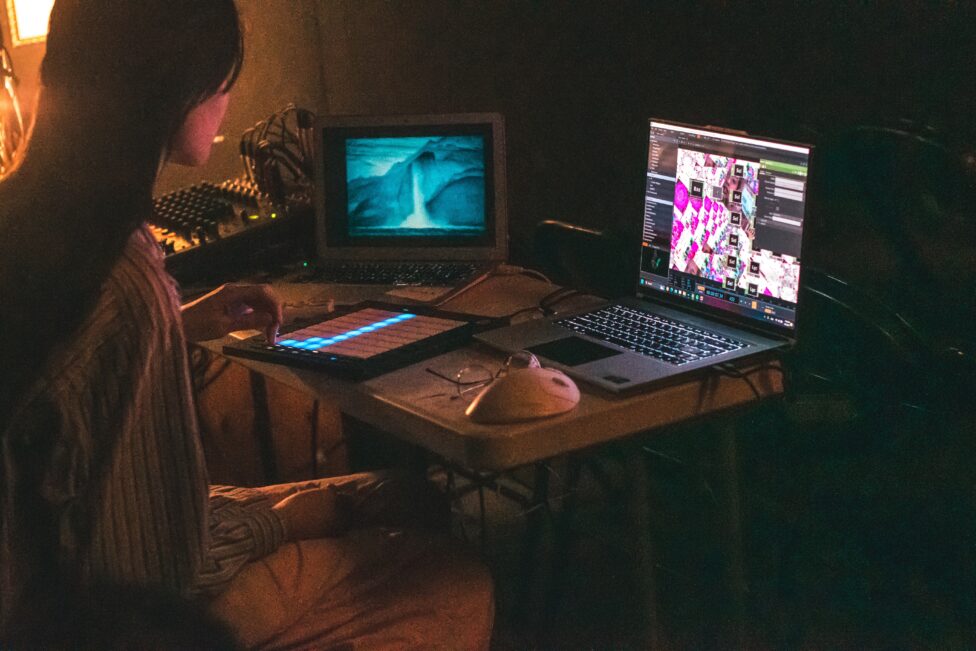

Photo by Alexis Welch

[ID: Sylvia sits in a dark room during “Lullaby Machine,” between two brightly-colored computer screens. They assemble pieces of a digital collage.]

CDA: I had this moment when the Metaverse was gaining traction, where I deleted every single post that I’d ever posted, removed every follower, and unfollowed everyone. My Instagram had gotten increasingly more personal, while I was also growing aware that I had this unseeable audience and that I was a digital subject. What do you do with that? I made this post referring to my followers as “Panopt-Icons” and shared that everything feels contrived, and I don’t know how to deal with this digital personhood. It was incredibly too personal for Instagram.

MS: But there’s no line anymore! What’s earnest is meme-able and a nuanced tone is entirely blown out.

CDA: I was thinking about what you were thinking about, about audience. My ego doesn’t like the idea that I am seeking attention through the internet, or curating my life for an audience.

MS: I would be lying, though, if I said that this didn’t inform how I think about myself as a “capital A” Artist. Visibility is definitely tied to my feelings of validity as a creative person. Even if the content I’m posting has nothing to do with an actual, tangible creative practice, it doesn’t matter, because I think the internet makes my creative practice inextricable from “me.”

CDA: Because of the internet, you are also selling your self as an artist. People are buying into you as a person. And so you do have to curate some kind of…

MS: …digital personhood, yeah.

It can be difficult to feel like I’m being true to what my creative impulses are. I’ve had these moments where I wonder if my creative impulses have sort of subconsciously morphed into the more marketable version of them. This is a lot of what draws me, frankly, away from a packed schedule of daily dance classes and getting my face out into the Hashtag Big Dance world. My hesitation is that I will lose some of the true motivations for what I’m making. I keep arriving at the realization that production was actually never what it was about. And I am trying to commit more to daily practices of creative ritual or habit that have nothing to do with making something that other people see.

CD: I’m still forming this thought. You know how people say “the girls who get it get it? And the girls who don’t don’t.” Then there’s women being so feminine that it’s camp.

There’s something exciting about leaning fully into the fact that you’re performing to an audience and saying: I don’t give a fuck. Okay, there is an audience and you’re watching me. What are you going to do about it, huh? Is it so bad that I want attention sometimes? Or, is it so bad that there’s a part of me that’s not authentic all of the time?

We’re living with such confusing expectations to balance digital and “real” self-expression, and it creates this disorienting funhouse of mirrors. Why do I expect myself to be this angel of an authentic person? What does that even mean? What would that even look like? I am changing all the time. I could make a caricature out of myself on the internet. I could play around with the audience. I don’t have to put so much pressure on myself to be earnest and be authentic. Part of me wants to protect myself, but I also want to be earnest.

MS: It’s a double edged sword. It’s impossible not to fall to either end of those spectrums. When I’m devoting brain space to thinking about how I occupy space online, the repetition and the visibility and the false universality of the platform mean that my earnestness is at the same time a performance of myself. Both are true.

CDA: Having an audience on the internet for whom you’re curating an image amplifies this thing that’s already happening in your real life. It feels like drag or like gender, in a way.

Sometimes I have thoughts, like: “Let people think I’m a woman. I don’t give a fuck, I’m gonna be so womanly it’s unreal!” And then another part of me is like: “I just want to be beautiful in a not-really-specifically-gendered way!” It does feel like part of me says everything’s drag. Another part of me is tired of performing.

MS: There’s no off-button. And that’s the terrifying end result of a lot of these spirals of conversations—that I love having, by the way. It’s this overwhelming feeling of fragility and helplessness despite how foundational the internet now is to ourselves. Whether I am actively participating in it or not, it is now so ingrained in how selfhood is reproduced that there’s no escaping it fully.

CDA: I don’t want to be seen. But I want to be earnest. And I can’t see my life without performance. I guess it’s just one big rock-up-the-hill. You know what I’m talking about?

MS: Sisyphus? Oh, I know him. We’re close.

CDA: The Internet does feel like a chamber of mirrors. It’s created some partly good but terrifying shifts to humans’ connectedness.

MS: I wonder if that chamber of mirrors translates to a sort of echo chamber in the “real world.” The internet has been part of this feeling I’ve been having with some dance performances I’ve experienced in this city. I’ll go to multiple shows that I expect will be quite different from one another. Instead, I end up having a sense of déja vu, of feeling like: “Hold on, I’ve seen this before.” I’ve seen the way that this person is moving, this technique of audience interaction, this familiar title in all lowercase letters. Then, I’ll connect the dots through the internet and realize: “Oh, these performers went to the same school and trained with the same person and were in the same company. And oh, they had the same residencies and mentors and work history in New York.” And I have this feeling of repetition, with these iterations reflecting back at each other, faster and faster. The internet seems to fuel this.

I’m not quite sure what to do with that feeling. I’m fairly new to New York, so I look at this place and see a more stark reality than is probably accurate. I’m unaware of countless corners of the dance world that would probably shift my perspective of the “scene” as an echo chamber at all. At the same time, I feel skeptical of finding a rootedness, if I’m interested in being disconnected from the internet’s hold. And I’m curious what the alternative is.

CDA: I think that touches on marketability. I say this as someone who is still very much on the outside, looking in. It does feel like many movement artists assimilate similar movement styles and aesthetics that they know will get the job, or the grant, or the audience. And those aesthetics are typically white and postmodern. If you want to incorporate social dance, improvised forms, or anything outside of a white postmodern aesthetic, it seems harder to get these already scarce opportunities for jobs and funding in dance. I think that has a lot to do with the New York echo chamber, too. Maybe the proscenium stage isn’t the ultimate legitimizing platform of your art anyway. But artists do need to make a living somehow.

MS: And when I think about my personal artmaking, the experiences that have been most meaningful have been things like improvised dance and music shows in parking lots, of all places. I do credit the supposed limitations of going to school in a rural place and partially during the pandemic with highlighting for me some alternatives to the Ultimate Proscenium Stage Dream.

CDA: I’m new to New York, but I am finding there seem to be many back alleys here that aren’t so obvious for dance. I’m just not in it enough to see. I’m super interested in making the rounds at all of the must-see performances, and also seeing what’s beyond the most prominent stuff.

MS: And time is important for cultivating relationship to creative community. It’s easy as newcomers to spell out things that are wrong and limiting about a place we’ve just arrived to. But that’s definitely a question for me, too: Is there a particular feeling of connection to creative community that I should be anticipating? I don’t want to say it’s arbitrary, but on some level, I recognize that connection comes from a commitment to doing the work, to co-creating what I want to see.

I have relationships with both a rural creative community in Vermont and here in New York. They’re not entirely separate, but there are huge distinctions between how people have to approach artmaking in those places. I’m curious to see how my own practice aligns with the necessities of cultivating a creative life in those different environments.

CDA: Yeah, sometimes New York does feel like the end-all be-all of dance or performance, but it really isn’t. I went to school in Wisconsin, and there’s great arts funding happening in the Midwest, a really interesting DIY performance scene in Philly, and all sorts of cool pockets of artmaking that I’ve yet to tune into. It’s good to remember that New York is one part of the web. I’m trying to be less critical and just to take it all in. I think part of being critical is just being self-conscious. There’s that audience again.

Test 6

Wilmer Wilson IV, Study, Portrait with Hydrogen Peroxide Strips (2014). Photo: courtesy of the artist.

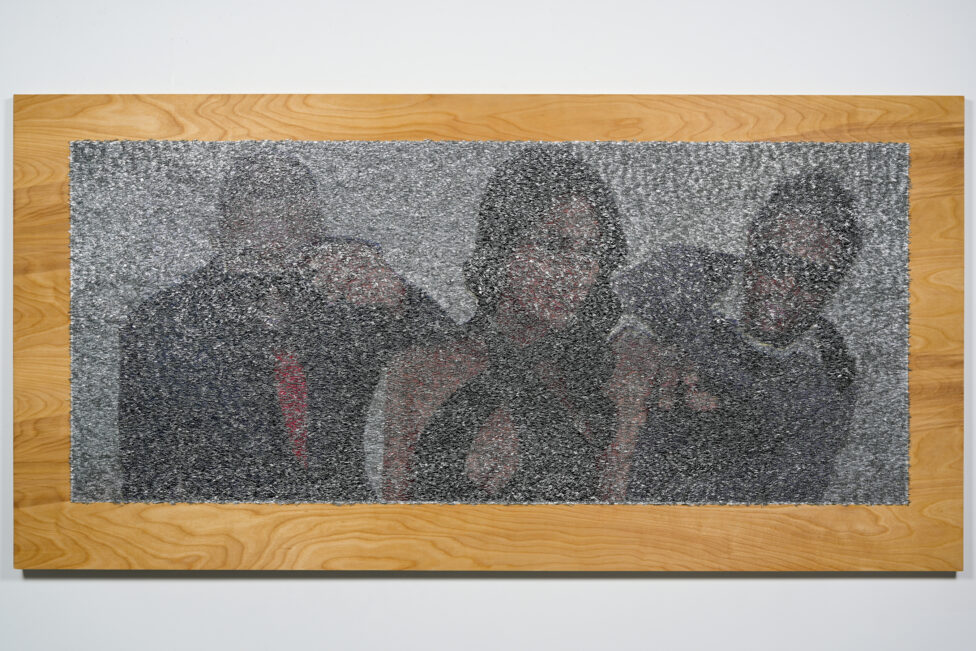

Wilmer Wilson IV, RID UM (2018). Photo: courtesy of the artist.