The academic relationship between a student and a teacher is a very distinctive phenomena. As a student, engaging with and learning from a teacher who deeply connects with you, will carry on as you move on with your career. As a teacher, you get to guide collegiate journeys of brilliant young minds while simultaneously learning from the students’ ever-inspiring ways of thinking. Each relationship has its own unique dynamic, and the one between emerging movement artist Tatiana Borchetta and artist and professor Catherine Cabeen is no different. Based on a relationship Tatiana and Cabeen cultivated at Marymount Manhattan College for the last three years, this conversation beautifully captures the spirit of mutual respect, critical curiosity, and mentorship.

— Takahiro Yamamoto, CC Co-editor

This conversation has been edited for the purpose of publication.

Tatiana Borchetta

I view dancers as being no different than any other worker, which is why I am interested in the theme of commodification. Not only are dancers themselves commodified as in their bodies, but so is their work: the fruits of their labor. If you’re a woman, then that commodification is twofold. I thought we could maybe contrast you being a seasoned professional—you’ve danced for a very long time, you’re now a professor and a choreographer—and myself being a fresh college graduate. I’ve heard you and other people talk about how the industry has changed, and how back then you guys used to dance with a company or a choreographer forty weeks out of the year. That’s become a very rare occurrence now. It’s all short-term contracts. What are your opinions on it? From my point of view, the dance world is undergoing a crisis.

Catherine Cabeen

I think it’s a crisis that has been a long time coming, and that it is necessary to shift us into a place of more equitable economic compensation for the immense amount of labor that goes into dance production, practice, community engagement, and protests. All of the different ways in which dance is engaged require a huge amount of labor that should definitely be compensated. That labor is oftentimes in conjunction with a great deal of expertise. Even if you are a community organizer who is organizing non-trained bodies, community organization is a skill. I will say that 40-week contracts were always rare, but things do seem to be shifting more towards project-based models, which makes it more difficult for dancers to invest in process and community, let alone to make a stable income.

TB

One has to take into consideration the network of conditions when determining compensation.

CC

Absolutely. I came of age in a dance world where dancers were considered disposable. Especially if you’re female bodied, there are nine hundred more of you. So, if you’re tired, if you’re injured, if you dye your hair the wrong color, if you cut your hair, if you look funny at the director, you’re just out. And the next person comes in. So, when you’re in a culture like that, where bodies are so disposable, it’s very difficult to advocate for one’s rights and to advocate for being respected as a thinking sentient being. And so, I think that a lot of the shifts that are happening now are connected to respecting the fact that dancers are whole people, that dance is labor, and that people deserve compensation for their workeven when they love it. I’m definitely in full support of that. I think what’s complicated is that those demands are coming intrinsically from within the dance field. Dancers are asking you to be paid, but we have no more money. So we need to keep working in organized ways to shift arts funding structures and business models.

TB

This is something I have been trying to reconcile with as I am getting closer to graduation. I’ve met dancers in their late 30s, in their 40s who are still active performers, and they’re still not stable. They still have a side hustle or a daytime job. Then, I ask myself if that’s going to be me.

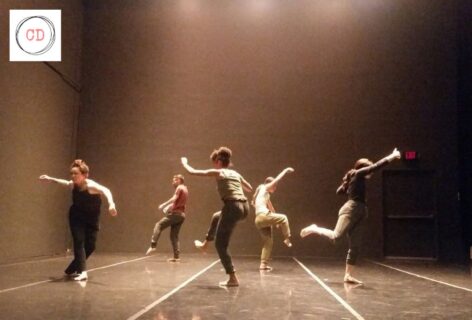

Photo by Leandro Justen.

CC

Dance was never, and probably still isn’t, something you should go into for the money. There is a really problematic relation between dance practitioners and funders/institutions, the edifices which uphold the status quo. Dance is the least funded of the arts because it connects to the body, the body itself then is associated with femininity, with nature. Patriarchal heteronormative society has decided these things to be less than, and worth less than.

There is also the association that people make between dance and emotional expression. That is not considered a masculine trait in our male dominated society. There are all kinds of things that connect dance to gender in a binary and hierarchical format that keeps it in this category of receiving much less funding than a lot of theater arts. This makes the revolutions that are happening inside the field really tricky because we’re wanting to advocate for more pay, but we’re fighting over the same like five crumbs.

TB

I often talk about how dance exists at the intersection of politics and aesthetics. They’re deeply intertwined. In my research, I combined aesthetic and political philosophy to generate a theory of dance. I elaborated my thesis The Commodification of Dance and the Privatization of the Body upon two premises. Firstly, dance is inherently political because it involves the body you need human labor to create value. Secondly, dance and art, more broadly, are political because they also have the ability to reconfigure conditions of perception and what we then perceive. What gets to be seen and what does not. And that goes back to funding. There’s always an agenda behind what gets funded. When you look at the history of dance with Martha Graham, it wasn’t a coincidence that her work was funded by the US government during the Cold War. The same government responsible for the Red Scare and McCarthyism. Graham went on to perform in countries that were ‘susceptible’ to communism. So these funding institutions you mention are attuned to the ideological strength of dance. Considering your past tenure with the Graham company and Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane company, I wonder whether you resonate with the characterization of the body as a simultaneous site of repression and dissent since both companies hold disparate values at the core of their choreographic process.

CC

Absolutely, the fact that the body is both a site of oppression and of resilience is one of the most fascinating things to me as a dancer, in terms of my practice, as well as any kind of creative product I may create. Most of my own work is at the intersection of healing and politics. I agree with our feminist ancestors that the personal is politicalour bodies are inherently political. They are also the whole with which we experience the world. Our bodies are these living sensory apparatus that are vulnerable and delicate. I think that the ‘yes and…’ of the body as a site of oppression and resilience is what makes dance such an exciting art form. When I was working with Bill T. Jones, in the rehearsal process, we were having active conversations about what was happening in the world around us, and what had happened historically, to create the world that we’re presently living in. And then he would ask us, “what does that look like in dance?” Bill would always come in with assignments reading assignments, written assignments, compositional assignments, and challenges. None of them were like, “‘Here’s a fun task”’. They were more like: “make a dance phrase that convinces me that dance still matters in a world where these kinds of things are happening.” And that was a real push to think about how one’s individual body, and the diverse collective of bodies in the company, connects to political activism. Certainly, when I joined the Graham Company, things became much more homogenized. I was literally handed three VHS tapes, and told to go home and learn the parts. So, they were really night and day experiences.

TB

Having worked with Bill T. Jones whose works are essentially like social commentary, would you say that artists have a duty towards their community?

CC

You know, there’s a part of me that wants to say, no. I don’t think it’s a duty. I think it’s a calling. Some people are called to do that work, and some people aren’t. However, I feel like we live in a time right now where way too many people are opting out of their responsibilities towards each other and to the planet. I am more curious about the word duty and what that means not just as an artist, but as a human being. I feel like we all owe each other a lot more in terms of consciousness, respect, and connection, particularly to the planet, let alone to one another. What do you think about the word duty?

Photo courtesy of the artist.

TB

I don’t think of it with a pejorative connotation. Because we live in a society amongst others, we do have a duty towards one another. Our status in society as artists comes with the acknowledgment and responsibility that art is transformative. It’s an aesthetic form which means it involves our senses. We can see, hear, and feel it. It’s transformative because it can challenge reigning modes of perception and introduce new perceptual episodes what we see and what gets to relish in that visibility. No dance is devoid of an ideological underpinning. It just depends on what you’re trying to render visible. And you see it in the book, Stepping Left, when two disparate dance movements were developing in geographical proximity to one another near Union Square in NYC in the early 1900s: Modern dance which was considered art and the communist dance movement which wasn’t art because of its overt politicization.

CC

If we just focus on artists, I think artists do have a duty to be true to the forces that move them. I don’t think it needs to be agitprop theater to be political. Graham did make works, like Deep Song, that dealt with the Spanish Civil War. She had an awareness of what was happening in the world around her. But certainly, what Edith Segal did with the early communist movement was much more agitprop, which was why that work was both celebrated and criticized. They were active in getting worker’s rights on the books, creating anti-racist performances. Stepping Left is a great book, because it’s one of the very few that talks about it. The issues of who gets a legacy and who gets written about is unfair, and needs to continue to be interrogated in terms of what parts of history…

TB

…what parts of history get to be preserved. This notion again of what gets to be made visible.

CC

Exactly, especially in something as ephemeral as dance.

TB

I want to go back to you characterizing dance as a conduit for the expression of one’s emotions. I always think about that within a larger context of late stage capitalism. Capitalism has managed to spread all throughout all facets of our lives have been commodified. If you define an aspect of dance as being the expression of our innermost feelings, it’s then not just our bodies that are commodified, the fruits of our labor, and our choreographies, but also ourselves. So that’s one thing I find really hard to reconcile. You find yourself having to yield to the laws of the market just to be able to survive. It becomes difficult to consider dance a means of self-realization.

CC

Well, that’s why we’re sitting in this office on the Upper East Side! I was incredibly fortunate to be able to be a dancer in companies where that was what I did. I definitely taught workshops and did some guest artist lectures or choreography during the time that I was active at the Bill T Jones/Arnie Zane and Graham companies. They did provide a modest living wage. I was able to just be a dancer. That was in the 90s and new millennium. And I feel incredibly fortunate for that. When I worked on my own work as a choreographer, I was living in Seattle. I had these great commissions and opportunities coming. I had funding from the city, state and county as well as private donors. I also had literally fourteen part time jobs and spent a year living out of car and couch-surfing with friends and family because I couldn’t afford my own place to live. Then I got my first full-time academic job out of that. I accepted it, knowing that it would compromise my ability to dedicate as much time as I previously had to my creative process, but also that it would allow me to eat. At that point in my life, that was the most important thing. It’s been really interesting for me in terms of thinking about art, my personhood and market value. As a full time academic, a lot of my time and energy have to go into the ‘highly creative’ pursuits of planning courses and curriculums. But also, my creative work is free to be whatever the fuck I want it to be because I’m just paying for it myself.

The hustle side of granting processes is a big game, and it’s only getting more competitive. There isn’t more money, and there are more artists reaching for this same pool all the time. That’s why I got really interested in self-funded work, DIY work. The Guerrilla Girls has a huge influence on me. Some members from the Guerrilla Girls came and gave a talk at Middlebury College where I used to teach. One of the things that they put forth was to “make cheap art.” They were like: “Don’t wait until you have like a Kennedy Center commission and nine million dollars for the fanciest thing ever, because then you’ll make one thing. But if you just make a lot of stuff, you’ll be able to exercise your creative potential, and get things out there.” There was something liberating in that to me as an artist. My work is not slick- it’s rough around the edges, but that means I’m not precious about it and I make what I need to express.

Photo courtesy of the artist.

TB

It’s an attempt to widen the parameters of what gets to be considered dance, especially now that so many of its forms have become institutionalized. In an institutional or academic setting, some call dance a fine art. I find it laughable. I don’t necessarily consider it a fine art. It’s first and foremost a social practice, and that’s how it started. And then it became institutionalized. In many cultures, dance is not something you teach in a sense of how ballet or modern dance is taught. It’s just something you acquire experientially. Whether it’d be in celebratory settings like the medieval carnival, or… for instance I’m Middle Eastern, and we have belly dance, even though I don’t like that term. We don’t learn it. We see our mothers doing it in social settings, and we just kind of pick it up. So even in the studio setting, instructing someone to move a certain way within a space in itself is ideological. It has an ideological function to restrict someone’s movement to the four walls of the studio, and to command the body how to move within these confines implies a sense of ownership. You feel alienated from your own body. This paradigm is one out of many.

CC

Dance at this point has many manifestations that are fine art as they are connected to elitist training and production models. And others that are social: they are passed down through family traditions and cultural traditions. When you look around the world, so many of the dance forms that we celebrate today come from historically marginalized and oppressed communities. These dance forms emerge as resistance and cultural identity. My understanding of that phenomena is that everything else, everything tangible, can be broken and taken away. The vases are broken, the paintings and the musical instruments are taken away, but if the human beings survive, what they have left is their body with their heartbeat, breath, and voice. Therefore, these beautiful forms of dance tend to emerge from conditions of intense cultural oppression. Those dance forms are often, as you described, generationally passed down through people in social ways. Then what is interesting and complex is that many of those dance forms became commercialized and pulled out of context in dance studios and are taught in extractive ways. We need to study the way that people move in different parts of the world under different pressures and different circumstances. It helps us understand the human condition. These styles of dance are sites of resilience and survival for the communities that they emerge from. We all need to carefully consider how/when we are engaging in cultural exchange and when we are extracting/appropriating in ways that add to oppression and erasure.