Over the last twenty years, Xavier Le Roy has radically expanded the field of contemporary choreography, through solo and collective research-based practice. His diverse works question the limits of performance, exposing the conditions that govern artistic production in the theater. Increasingly, Le Roy has turned towards issues of addressing and engaging the public, and how to stretch and redefine that boundary that establishes a perceptual relationship between audience and performer. In 2012 he premiered Retrospective at Fundació Antoni Tàpies in Barcelona. As his first museum exhibition, Retrospective extends his research into a new context, recycling his major works as material for dancers to sample, interpret and reconfigure as elements within performances of their own life stories. Here he discusses the genesis of the project, its current iteration at MoMA PS1 (until December 1, 2014) and the tension and looseness that arise as his oeuvre is transformed through the actions and words of other people.

__________________________________________________________________________________

Will Rawls: Before we talk about Retrospective and its placement at MoMA PS1 right now, I want to talk about the invitation to make it and what the context was. Where were you in your process when Laurence Rassel invited you to make a retrospective of your work?

Xavier Le Roy: No, she invited me with what she called carte blanche, to come to Fundació Antoni Tàpies and do something, whatever I want—this was her proposal. So, there was not an expectation that I do a retrospective. The work was decided through a process. I did not say, Ah yes, good, I can do this piece I have made or that I always wanted to do. It was developed through an exchange with Laurence. She had followed my work since 2000 and we met during the Kunsten Festival des Arts [Brussels] in 2001 where I had proposed to organize a series of events that had a fil rouge [red thread, a through line], related to the question of copyright. At the time, Laurence, together with Nicola Malevé, were working on open source, software and media—the question of code, to whom it belongs, to whom the software belongs.

Laurence has an interest in the question of process and the processing of things and ideas. That’s something she is looking for in her institution—how to share, how to propose an idea of coming in contact with art, or the art experience actually being a process—by putting this idea of process in the institution.

Retrospective by Xavier Le Roy. Photography_ Lluís Bover. © Fundació Antoni Tàpies

WR: The process through which a performance gets made is something that you’ve experimented with a lot in your work.

XLR: She pointed to this question in my work. She made her carte blanche proposal just after she saw The Rite of Spring [2007], which confirmed for her that I have an interest in the particular attention and intention of making this relationship between public and performers a subject matter. That is where she sees the potential for process.

She didn’t give me any instructions.

The first thing I thought I would do is to show my works in the museum. It was only when I got to Barcelona that I understood it wasn’t going to be possible to show the works.

WR: To show the works, intact, as they have been performed on stages?

XLR: Yeah, because there’s no way to install a theater “situation” there. It was not fitting because the main space of the Fundació Antoni Tàpies is full of columns. [laughs]

WR: So, you arrive with a suitcase of your work in front of you. When did the idea of Retrospective, both as a title and concept, take shape?

XLR: There was this first realization: I’m not going to be able to do what I thought. And the second thing is when Laurence said it would be an exhibition lasting 2 or 3 months. She said, “Maybe you do two days of performance, but then we have to think: what will happen in the two other months.” That is when I understood, Aha, I need to think about something in time that will last the duration of that period. It should be an exhibition, and I saw in the idea, retrospective, something that would be more specific to a museum than a theater, a time and space that brings things together, which, at first, were not made to be put together in the same space at the same time. This is something that seemed more specific to visual art than to performance in theater. I was also thinking about this word retrospective and looking backwards and how the past is part of our experience of the present.

Retrospective by Xavier Le Roy. Photography- Lluís Bover. © Fundació Antoni Tàpies

WR: How did choosing the word “retrospective” put pressure on you?

XLR: If I had been asked, I probably would not have been able to do it. I think I wasn’t conscious of the weight that the title would bring with it. It was only after some people said, “So, you’re doing your first exhibition and you’re doing what an artist normally does at the end of a career.” I was more focused on using the past and bringing the past into the present, which I connected to my work, Product of Circumstances [1999] where I first used that operation to produce a new work. I was thinking about how the looking back produced something in the present moment.

WR: As I’ve been working as a performer in Retrospective, I’ve noticed there is a lot of repetition and recursiveness in your work. In Self-Unfinished [1998] there is a recurrent backwards walk; in Giszelle [2001] there’s a rewind and fast-forward of language and movement. In Low Pieces [2011] there’s this statement to the audience: “We can continue the conversation later on during the performance”. There is often a “return” that happens in the work. I thought maybe the idea of retrospective came from that.

Xavier Le Roy’s ‘Retrospective,’ photo: Will Rawls

XLR: I think you are right. I didn’t see that in the way you put it. When I consciously did this for the first time in Product of Circumstances, I was using the idea of recycling something. In responding to a commission, I have often recycled things that already exist. Not that anything is ever really new; you always reuse things. I would make the distinction between consciously choosing to use something that already exists and doing so unconsciously—taking something extant and transforming it without knowing. In retrospective, this is consciously done. We use things that pre-exist and place them in another situation and out of this, something new is produced, And it’s still possible to recognize and identify the material that is used. There are different levels of this. It is also the strategy in Giszelle. There are two halves of the performance—one which is exclusively using material that people who are inscribed in Western culture will recognize or associate, very easily, with preexisting representations of bodies, and the second half, which is not based on this operation. Product of Circumstances also plays with this in a slightly different manner. When I say, “It was the ending of a three years long love relationship,” yes, it’s not something that you know, but you might recognize it because you might have had that experience also. The idea of reusing, I think, is a stream. But it’s also produced by the necessity of responding to the artistic production machines that we navigate; recycling is a strategy in order to respond to this. When I have to produce new material, for me that’s really complicated. Having the sense that you look for something that would become the movement, that is the material created for the new work; it is so difficult. I cannot do this very often.

WR: Movement invention—How does one even define the science of movement invention? It can be sought through activities you do or through sources of inspiration and feelings, but these aren’t the same as the movement that emerges that is new. And then also, it might be new for your body but not for another body.

XLR: That is the complexity. In the way you produce movement you might engage a road that is new for yourself but definitely not for everybody; that is impossible. But you can use the strategy of reframing the movement so that it is new in another situation. It’s also what happens most of the time with things that you see in an exhibition; one takes something that is made in a context and places it in a different one: the exhibition space. If you also think of the market, you see vegetables. They are not meant to be exhibited in the market. They are from the garden and made to be put on your plate, but in between they are put in this place where they “don’t belong”, or more precisely it’s not a milieu where they are alive or are produced in the first place.

WR: And that place where they don’t belong has become naturalized in the journey of that vegetable to your plate.

XLR: It produces an interface with the consumer. I think the exhibition space is like this, not only there for consumption but to produce a set of interactions that are specific to that space.

WR: How did Fundació Antoni Tàpies allow you to move into new territory for yourself as an artist? How did you find a way to keep it interesting for yourself, so you could keep evolving?

XLR: As I develop my work through the years, without having a clear-cut moment when I’ve decided it, the relationship between the work and the public has taken on more and more importance. It became more obvious with Untitled [2005]—giving a flashlight to audience members in order to link the action of watching to both communal and individual action. Or, in The Rite of Spring, the idea of distributing the speakers under the audience seats and addressing my conductor’s movements to certain people across the room, as if they were musicians in an orchestra. The theater is a situation that produces relationships, and these relationships have a certain politics and poetics, and they are distributed and separated into two qualities: active and passive. This line of separation for me is somehow the question. In a way, I accept it because I use it, but also, I don’t. I try to transform it. Or, in other words, I would like to accept it under certain conditions, so I need to change the conditions or to change the theater. Some years ago I realized that this is what I do, trying to move these lines of separation; it’s in order to understand my relationship to the world, as an individual, in the group, in front of the group, part of the group. All these interests are at work in what I do and they produce questions, doubts, problems, satisfactions, enjoyments, sadness. The proposal of the exhibition space is to have another kind of this situation where relationships between people, between groups and individuals, between works and people, between people and work are also at stake.

This interest, to work in exhibition spaces, has also been activated by the work of Tino [Sehgal] as I have been involved in and followed, from the beginning, his thought and artistic project. I have been and I am very curious about why he wanted to use the visual art institutions such as galleries and museums, and how he did it. In the development of his work I saw possibilities; he opened up a way to deal with questions of these spaces and their potential.

WR: Among artists, we exchange these strategies, conversations and practices, and they manifest with different content or in different spaces but within power structures that we all manage together.

Going back to new movement, maybe it’s not possible to make new movement but—is perception easier to renew, somehow?

XLR: You can revisit the assumption of perception, I think. Staging is a good way of thinking of this. It’s possible to produce doubt in your perception and that’s a way of conjuring something new because it can make you say “I thought it was different.” I am interested in creating this trouble in perception, the illusion, the uncanny, something that appears strange but is actually totally normal. That is what happens when we approach each visitor in Retrospective—it’s very strange, and for some, frightening. But it also comes out of a totally normal action, a human being going towards another human, with no weapons, but maybe with a strange way of standing up that reinforces the strangeness and the uncanny.

WR: Yes, it all happens before your eyes. When I watch Self-Unfinished, I watch you going through a process of being you or, being a human being, and then transforming into a creature-like body by bending over and pulling your shirt over your head, and then coming back. In these transitions, my doubt arises but I’ve also watched the whole thing happen, so I’m experiencing both transparency and doubt at the same time.

XLR: And it’s made by both parties. It’s not only me, and it’s not only you.

WR: How would you describe the mechanism, or mechanics, of Retrospective?

XLR: It’s three rooms. The first room one could describe as a display room, where movements, actions and choreography are displayed for the visitor. The dancers choose and perform excerpts from my works and excerpts from other performances over the course of their training and careers. These excerpts are woven into stories they share about their lives. At the same time other dancers are presenting excerpts from my works, either in poses or in loops. The second room is where two performers are at work and/or engaged conversation with visitors. So they are not “on display” in the same way as they are in the display room because the conversation that they have with the visitors and the actions each one chooses to do in that room aren’t preset or prepared; it happens in the moment out of the frame given by that room. And in the third room there are three dummies, an exhibition of objects. In each of the three rooms there is something “at work” and something “on display” but with different proportions; in one, the level of “display is” more important then being “at work” and vice versa. The third room has something that is very much on display but at the same time “at work”—when we watch the dummies for a while they seem to move. I’ve never described it like this but it’s another way of describing the three rooms.

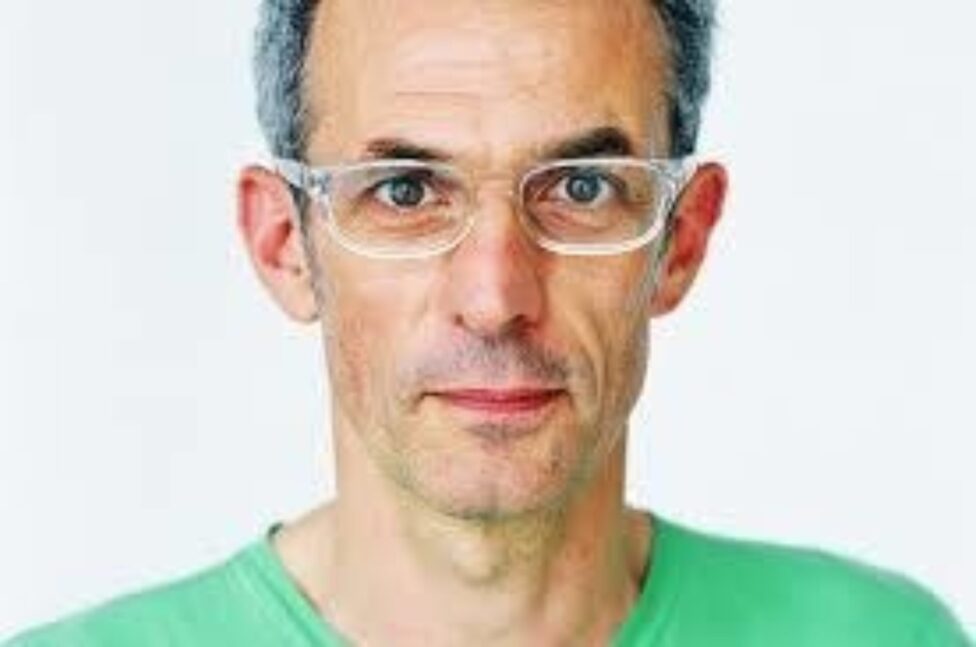

Xavier Le Roy

WR: Would you say that part of the process of display is a kind of inertness?

XLR: Yes but before we speak about that, there is another layer to describe which is that the choreography of the whole exhibition poses the question of, How can something that is continuous in time cohabitate with something that is discontinuous in time? Discontinuity of time is more specific to the theater. The theater is discontinuous in the sense that you have an engagement that is of a certain duration and it finishes. Beginning. End. One action or scene succeeds the next. Things are not present and visible forever; they appear and disappear. And the continuous is more related to exhibition space where you enter the room and the things are supposed to be there all the time continuously, even when you leave the room. So Retrospective is a sort of discontinuity that tries to exist in a place of continuity.

WR: How many times has this exhibition been presented before MoMA PS1?

XLR: Seven.

WR: So you are also negotiating with different institutions that have different capabilities, different budgets, different approaches to presenting and conceptualizing performance. What I think is interesting about the project is that you’re also negotiating the labor conditions for the performers. So I’m curious to talk about what is consistent or inconsistent from these Restrospectives.

XLR: One important thing that is, at the basis of this project is a question about objects. And how performing in an exhibition space that is made to display objects will involve a question of how much, as a performer, I transform myself into an object and the agency implied in that. That’s a line that I also relate to the work of choreography, which is very often happening in a group. Depending on how this group works together the material is very often generated from the bodies of individual people, except in a situation where the choreographer teaches the material to the others. But even then it is always about how a dancer negotiates this—and what the contract is. There are contracts and they are always subject to discussion somehow. In my experience of working as a dancer in different groups, there was always this moment of negotiation: Yes, it’s my material you used. And it’s also about what you want as a dancer—you want to be involved in something that will make you find something from yourself, or produce something. But this idea of “from yourself” implies “it’s mine”—but how do you negotiate this idea of property?

WR: Or remain conscious, or not conscious, about it.

XLR: Exactly. It’s consciousness and unconsciousness that are at stake. And it is very exciting to work on that, if one can make it somehow productive and not only a subject of conflict. Conflict is also okay, but trauma, let’s say, is a problem. This is maybe a long deviation but I think to answer your question I have to go here. There is, for me, a necessity to include this question in the work—to put it to work—because I know I do not want to assume that it is simply possible to perform in the exhibition space all day long in order to replace the objects.

When I look at a person doing a performance, there is something in my mind that comes up. I enjoy the movement, the reflection about what these forms produce, and then there is a moment where I think, What do they think?

WR: Because they are thinking. And that’s part of the content already.

XLR: I’m curious about that. One can think that this content is also visible. They think about the task they have to do, how the role is negotiated; this movement needs this attention in the body, et cetera. So of course as a practitioner I know this is going on for a performer, but I also know there are potentially other things, and I’m curious about those. I have a desire to try and show this, not only to represent it, but to use it as our force. In the performance, our labor is our power and is also our means of communicating. Out of this exchange, out of this communication, comes feedback. It is a way of asking, How much do I want to be an object? How much do I want to be a subject? How much, imperatively, do I have to be an object? How much, imperatively, do I have to be a subject in this situation? I relate this to daily life, Do I want to have many choices and therefore have to choose all the time? Or do I want to have only one choice imposed to me all the time? Of course I would like both but how? It seems difficult to find a satisfying balance between both. These possibilities are not very well distributed between people in our societies and it’s extremely difficult to build a situation where that would be working differently.

Xavier Le Roy’s ‘Retrospective,’ photo: Will Rawls

WR: There’s also a dichotomy through which dance can be an empowering or disempowering practice. As you participate in an artistic process, you accept a certain amount of intervention into your own body and mind, which, at times, can be traumatic. When I’m at PS1 performing I think about this—how to delineate my power, vulnerability and independence. There’s also a frustrating part, which is that, ultimately, while on the job, I cannot entirely break out of the frame of your work while telling my story. And that is a tension that I think will stay with me for the duration of the exhibition. I think the performers experience this tension at different intensities, or focus on other tensions. And then furthermore, the museum framework cannot be exploded or escaped while on the job, but I am still curious about how to work towards this.

XLR: It points at the necessity to have this museum frame and structure in place in order to find out what you experience, but also, to encounter the limits of it. Hopefully it doesn’t produce a cynical situation. This is my hope. You have signed the contract with these limits, my works, the museum, the fact that this museum is in this place, in this city, all these things—that is what we play with.

WR: How does one perforate the limits of the museum? Maybe it is by presenting or performing in such a way that a visitor carries this performance with them, extending the experience beyond the site of the museum. But, sometimes, the virtuosity of performing so well that someone remembers you, can be a kind of hyperbolic objectification of your performance. Catch-22?

XLR: I think one cannot break the limits of the museum, but maybe we can transform or extend them.

This might be an interesting survey to do with the visitors, if, when they go out, How and what do they remember of my work; How much what they take with them is actually this exchange with the performer(s). I’m almost sure that 80 per cent of people that don’t know anything about my work prior to Retrospective, who were not expecting to see performers in the space, who were coming to look at sculptures and pictures, leave with the impression and memory of the story of one of you, or two of you, or three of you—and my work and my identity actually disappear.

WR: Or they leave with a cacophony of impressions.

XLR: That is what I hope. In the end, the structure and the frame have been necessary to produce attention for you.

Xavier Le Roy’s ‘Retrospective,’ photo: Will Rawls

WR: This is something that Jenny [Schlenzka] brought up when we had that reception, she was thanking the performers and was saying, “Day by day, it’s looking more like a group show than a solo show.” But I don’t know if the group show will ever supersede your authorship.

XLR: That is, I think, the eternal question. [Long pause]. This reminds me of the intent of doing the opposite. When we were doing E.X.T.E.N.S.I.O.N.S [a collective authorship research project, 1999-2001], the intent was to present our work as something that is by these people. However, on the side of the public, institutions or the press, there was still the need to attach it to one name or one person, which at the time was me, being the project’s initiator. So then this group was full of the usual tension, all the clichés of what can happen in group work, cycles of exclusion and inclusion. This is, from my perspective, less productive than the situation that we have with Restrospective, which is, like you say, framed under my name, and yet the visitor’s experience can be of a totally different nature than that of my artistic signature, and the agency of the performers can be questioned, discussed and exposed.

WR: As the performers present their material each day, weaving our stories and dances into yours, Retrospective finds ways in which it can speak about things that your previous works don’t speak about. The subject matter and subjectivity of your work may be extended through us, and vice versa. But one thing that comes up for me is this idea of emotionality, especially when someone tells a story that engenders an empathetic response from a visitor. I don’t really associate your works with having this kind of exchange around empathy or emotional content, but I could be wrong. So, in my mind, when this emotionality, which has been “left out” of your work, reappears inside Retrospective, it throws your work into a different light. I am sure you know this and invite this. But by inviting these kinds of unforeseen contents, are you consciously inviting an undoing or a critique?

XLR: Emotions are not a driving force to produce my work but they are also not absent. Or more precisely they conduct my work unconsciously and I don’t use them consciously or try to express or represent them explicitly. In Product of Circumstances, I attempt to transform emotions into fact, to say we encounter different things in our life such as events that produce certain emotions, reactions, and other actions and these things become facts. That’s why I try to present them as much as possible as matter of fact—this happened and that happened. Love trauma is loaded by emotion and is a fact. If I go into details there is a lot of emotion, dark feeling, extremes from joy, pleasure, happiness to desire of death. When I say, “a three-year long relationship ends”, there are all of these emotions and feelings behind this statement. So I don’t use the actual emotion—that’s not a driving force—but there is a relation to it about which I also don’t know. Maybe it’s why I do all this work. When I did Product of Circumstances for the first time in French—somehow my voice went up and down because it’s my mother tongue. Suddenly my voice reflected a trace of emotion. Or, while performing Product of Other Circumstances [2009], I have cried several times. So it is permeable. I am permeable to this. But like you say, Retrospective allows all this signification and meaning in my work, which has been classified, from a certain perspective, as intellectual. Which I think it is too hasty to classify it this way.

But I guess your remark is right, by doing Retrospective and having all these subjectivities that use the work and say “that’s what it means for me, and what it does for me”, they create a multitude of relations to my work and sometimes it activates, via personal association, some emotionality. Therefore the “subject matter and subjectivity of my work”, as you said, may be extended and not reduced to be “intellectual” and elitist or difficult.

WR: A dancer will talk about a moment in their life that involves a certain kind of dancing, and then, in the palette of your work, there is something that reflects that. They will use your work as a substitution. And we choose when to substitute or when not to. We also choose what not to share of our lives. I love this idea of mentioning a decision not to share certain information as a way of creating a space between the performance situation and me.

XLR: It is also a way of saying, “It’s my choice.” That is important to me. This sense should be very present. To come back to your question about undoing my work: that is not a concern, it is something that Retrospective does in a certain way but it is not a desire of undoing. All the things you speak about, I also discover by doing.

Xavier Le Roy’s ‘Retrospective,’ photo: Will Rawls

WR: So what happens after Retrospective that is not a retrospective? What are your questions these days?

XLR: I don’t know yet. I’m a bit taken by the stream of doing Retrospective again and the curiosity of what that does in each place. At the very beginning, the frame was much tighter: “You use my work. You do an excerpt of my work and you talk about yourself through that work.” Already in Barcelona there was the necessity to perform things other than my work. Then from Barcelona to now, I think the necessity of using my work is still there, because it’s necessary to produce that frame. If we don’t have the frame, then we don’t have this resistance. It is the negotiation with that frame that should be loose. It is loose from the first edition at Tàpies. But how loose? And not in the sense of more or less loose, but in the sense of, What quality of looseness?

WR: Some people might want to perform an excerpt of Self Unfinished perfectly and other people might want to perform it imperfectly as a form of resistance. That’s one way I’ve seen this looseness. There are numerous strategies for bending and playing with the frame, the material, your own story, and to an extent, the overall choreography of the exhibition.

My last question is, if you had to ask yourself a question at this point, what would it be?

XLR: If I think about the possibility of extending this into a form that would not use my works as a frame or as material, I think that’s the question—Can the choreographic structure developed to exhibit these live materials become generic or, is it specific to my work? Can that choreographic structure be used as a frame for other kinds of material and subjects? How will that work? What would that do?