Timers

Abigail Levine leaves traces of her physicality by marking maps, charts, and telling us the story. She’s showing us accrual—that the body is different through repetition, not just renewed but changed. In the work below, Levine proposes that the dancing body is itself a timer. This work was proposed in response to my publication in December, Effort is Trying I am Trying, and I see Timers as a companion work. Each asks what the body can transmit onto the page and how we can visibilize our layered inner logic that lets us keep going.

—Londs Reuter, CC Co-editor

When I choose a place in Manhattan to meet someone, I most often suggest Sake Bar Satsko in the East Village. The bar is particularly well-suited to hosting the hazy intimacy between a pair of drinkers. It seats no more than 20, and the entrance is up a set of stairs on a residential block a 15-minute walk from the nearest subway station, so you always go there on purpose. Most of the people who do show up are from the surrounding neighborhood or are friends of the bartender. I brought my friend T. there, pleased to introduce him to someplace in his own neighborhood. T. is a theater director and, at the time, worked at a large museum curating performance. I described what I had been working on. Really they’re just idiosyncratic clocks, I said. Idiosyncratic clocks, he repeated. We got drunk, which made paying the large bill just a question of numbers. We walked outside. The night felt cool and unhurried.

Timers are activities that, in their repetition, record the accumulation of time. Each collects a different interval—minutes, hours, days, months, and years—and one records movement, which marks time in its own way. These activities have evolved over some years, as I looked for ways to record dance—its movements, force, effort, repetition. I came back to them during the first months of the pandemic, when the marks they left reflected my increased attention to the passage of time, brought on by the sudden spatial limits imposed on our lives.

—Abigail Levine, 2024

Jog (minutes)

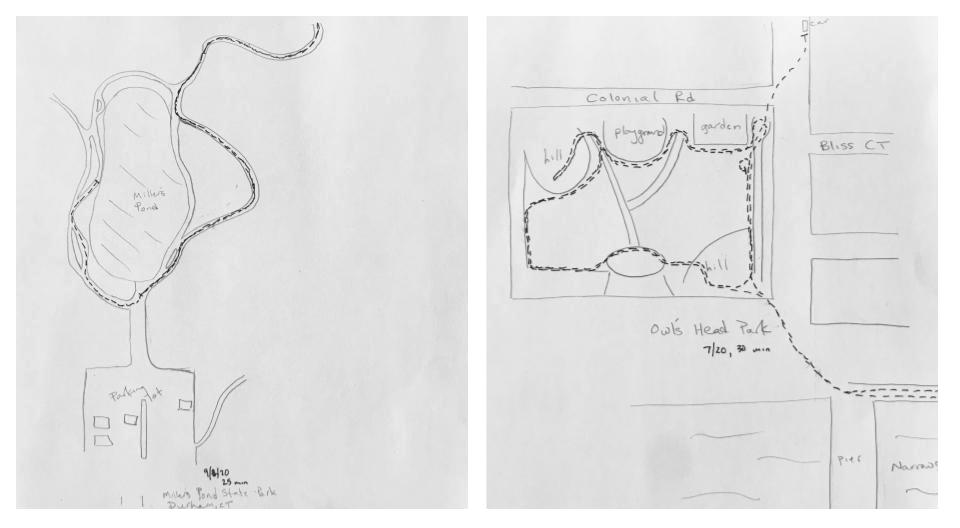

This is a record of the ground you cover and how long it takes. If you jog, record your jogs. If you walk a dog, walk to the store or work, record that. You will need to time your progress.

Draw a map of the area on which you run. You can do this from memory or work from an image, if you want to be more precise about scale. Label the map with the name of the place and landmarks that you recall.

After you have completed your jog, record the route you ran over your map. If you cover the same ground multiple times, go over it as many times with your pen. Draw just as you ran. Label your route with the date and length of time of your jog.

Keep making these records—each one on its own map—for every jog you take.

Once you have come to know a territory well—how long it takes you to cover a given distance—you can begin to compose your jogs as drawings, attempting to complete an acres-wide visual composition in the time you have allotted for your run.

Pressure Lines (hours)

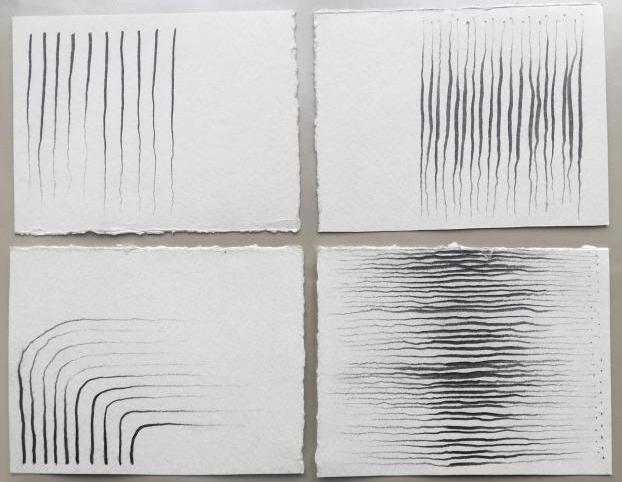

Sometimes you want to see the results of your actions. You want to be able to look back at your work and feel the one-to-one correspondence. I did that, I made that, it has not disappeared. Sometimes you want to push as hard as you can into a surface that won’t yield, something that will receive your force and match it.

Draw lines in graphite on the spectrum between lightest to heaviest—least to most pressure— applied from hand to pencil and pencil to surface. Some examples include: 100 vertical lines descending, lightest to heaviest to lightest; horizontal lines for one hour alternating heaviest to lightest and lightest to heaviest; lines radiating out from a single point to two edges, lightest pressure possible.

Involve your whole body in the drawing, directing or modulating its weight and strength through each line. Walking, squatting, reaching, crossing, extending, and folding will be useful actions. Jumping likely won’t. Each line that follows the same instruction should be done with the same physical intention.

The drawings that result are records of the time, evolving skill, and concentration of your action. It is not about getting the drawing produced, so performing the drawing distractedly defeats the purpose. When you are making lines, just make lines. Some of these lines will deviate from the pattern—mistakes. Eventually these will become the most interesting events of the drawing.

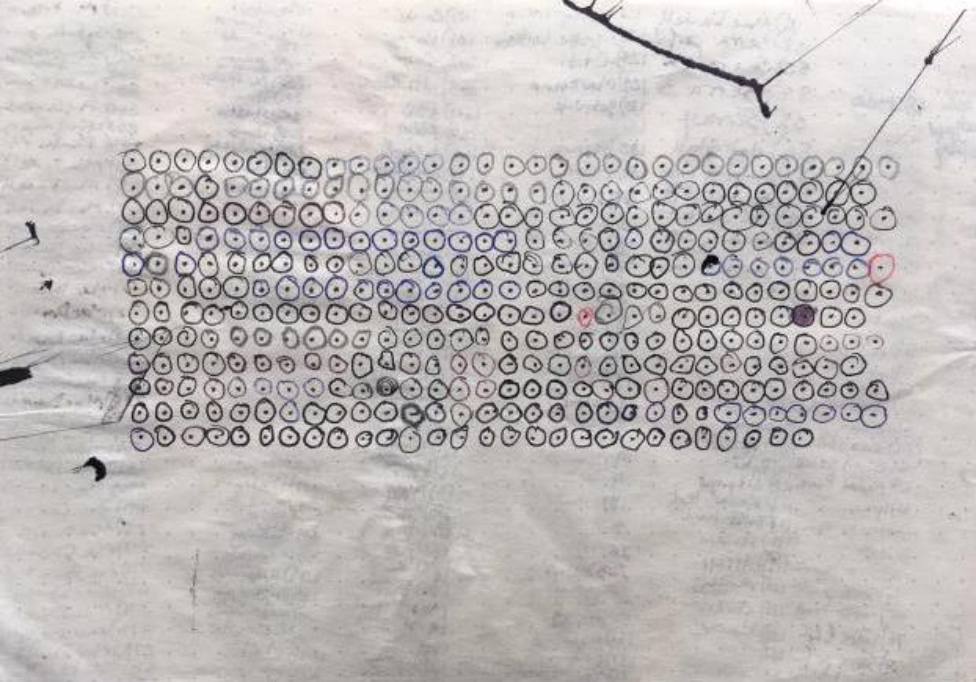

Calendar (days)

I knew someone who had a small tattoo of a circle with a dot in the middle. It was on the back of his left wrist under his watch. He recalled that the tattoo artist who inked it for him had asked, that’s it, and charged him the cost of a full tattoo. The mark was a reminder to get back to difficult work. When he needed a boost, he would slide back his watch and press his right forefinger into the tattoo, as if it were a button. He hoped it would give him courage. Four years ago, I felt directionless and thought of his tattoo. On my birthday, I made a calendar on graph paper—365 dots at the intersections of the paper’s lines. The year was divided into twelve rows for the months, beginning with my birthday. Each day, I put a circle around the day’s dot and made a note on the back of something I had done that day.

On a piece of paper, lay out 365 dots in month-long intervals beginning with your birthday. (If the month of your birth has 31 days, the first line will be 31 dots long. If it has 30, then 30.) The last dot of the 12th line will be the day before your next birthday. Each day, circle the dot of that date, flip over the paper and write something you have or will do that day. Write whatever you want to catalog—a task completed, the day’s first thought, who you have seen, or the weather. If you miss days, circle them. Only catalog events of the days you remember. Your calendar will collect dirt and will fade.

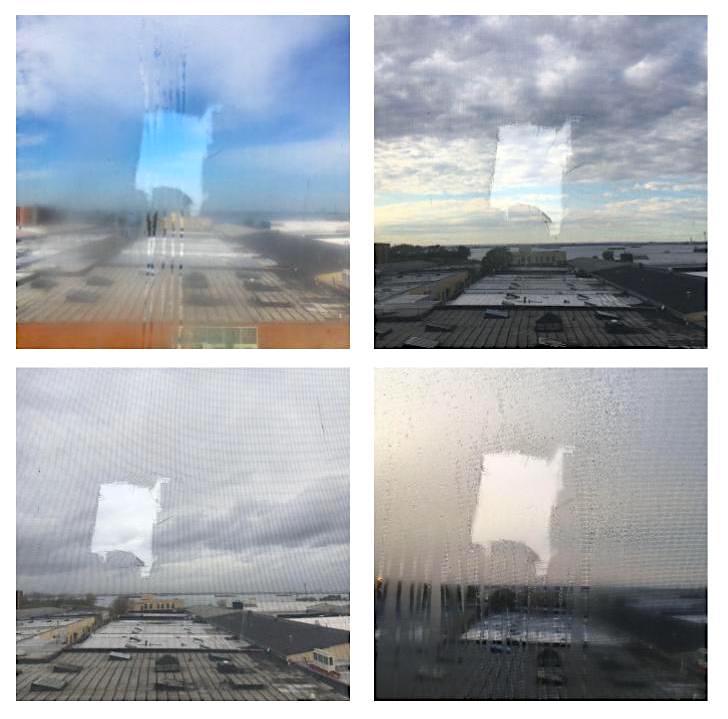

Correspondence (months into years, for two people)

Take a photo of a view you see every day. Send it to someone, the same person every day. The composition of the photograph is specific. It is not creative. Conditions create variation, not you. Raise your camera, pointing forward and shoot. As you accumulate a collection of the same view, when you go to other places, you may send boring photos of those places as well. Fill the frame with surface. 70% or more sky is recommended. Point at light sources, including the sun. You are not recording sights or capturing a scene. The photographs will not look like what you see when you look out at the view. They will look like that day.

Date your photos if your camera does not do this automatically. The score starts to take shape after three months. On Kawara made date paintings and often lined the boxes that held them with newspapers from the date that the painting named. Consider this relationship.

Utterances (movement)

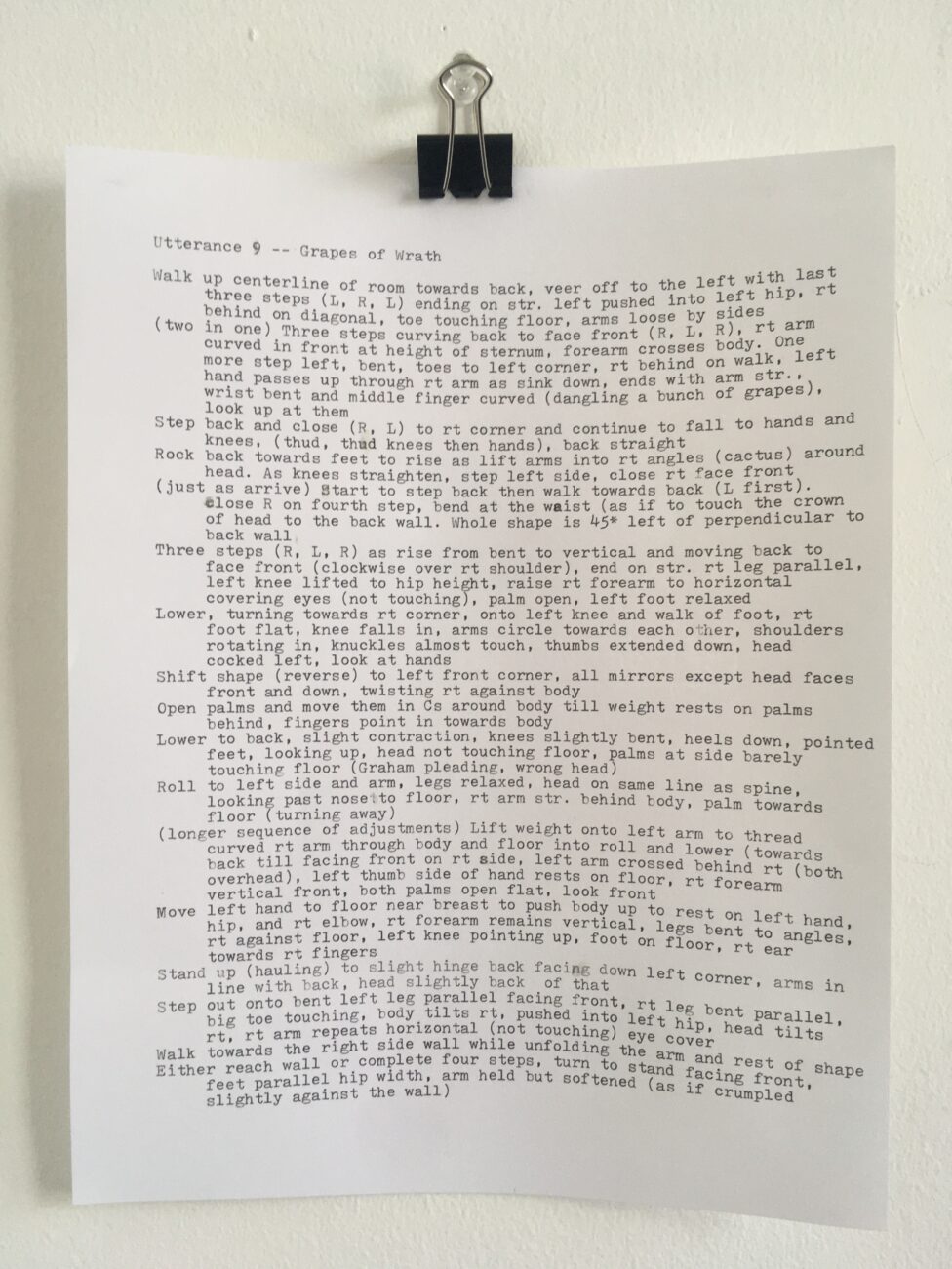

Utterances are movement phrases that I made to be performed while talking. I wanted the movement to feel like language. Each movement stands on its own, no physical or thematic through-line. Strung together they have the feel of a slide show on an old projector—one image, click, the next, click, the next. I recorded the Utterances on video. This spring, I started transcribing them on a typewriter. A two-minute sequence ends up as roughly a page and a half of text. If you were to go back and remake the phrase from the typed transcription, you would not produce the same movements.

Broaden the idea of Utterances to include the transcription of any sequence of movement or action you commit to memory or record. In typing out the sequence, you will develop a personal grammar for how you describe movement. Don’t worry about every detail; figure out what is most essential to a position, shape, or movement. Limit yourself to the occasional use of imagery and adverbs. Choose the words that best describe the movement as you understand it. Do not worry if this does not accurately reproduce the movement you have made. Futility is not to be avoided.