POSTDANCE Dialogues Introduction:

From October 14-16, 2015, MDT in Stockholm hosted a conference called POSTDANCE. The term wasn’t elaborated in any of the conference’s promotional material, but stood as a flag driven into the ground by an attractive mass of names— and international dance artists and theorists whose presence in one room for three days promised a lot. And these events are nothing if not promises—promises of assembly, of accordance and affinity, of disagreement, history being made, lines drawn, bottles emptied, of colorful outfits, being there when it happens, loving it with an absurd and faithful passion, being part of it, whatever it will be, but it doesn’t exist yet because the promise is mostly that if you show up, you’ll help create it.

The first content of the POSTDANCE conference was that it was sold out. Calls for tickets piled up on the Facebook page and each morning a line formed of people waiting for seats. The popularity of the conference and the fact that so many people traveled distances to join it, is owing to this on-point and impressive collection of speakers, but surely also to its proposal of this neologism, this elliptical “postdance”. The assertion of a term like this is an assertion of power, and to show up near the term is a reach to align with that power. Write down a word in the style of a title; write your name below it along with the names of four of your friends—there: you’ve formed a group and the group exists. A desire to be part of a vanguard, when a movement coalesces by the very fact of its being named, this is a bit what we were all here for. Of course we existed, of course we were lovers—our names are carved right there in the trunk of that tree.

But instead of a definition or a wave, there was what Siegmar [Zacharias] called the reenactment of a conference, all of us following the score the academy offers—keynotes were followed by panels, panels followed by catered lunches, and once repeated the whole day’s schedule trailed off into “let’s continue this conversation over a beer”. Some of us wondered about form. What if panels were called debates? What if the speakers were self-selected? What if topics were generated by participants?

What I cared about most was this inevitable micro conference—movements of words and bodies flickering below what appeared on the schedule. I handed out maple cream cookies that a friend brought me directly from the Toronto airport. Someone showed me on her phone that three people viewing the livestream of the conference had taken screenshots of her face in the background. Sitting on the benches out back, a few of us disagreed about when to say ‘performer’ and when to say ‘dancer’. We took walks along the moorings at lunch and looked at the houseboats. Mist settled on the water. We winked at each other. People moved about the theatre between at least seven types of seating including windowsills and laps and bits of floor. At one point I had the sense that every second person was messaging someone across the room with a joke or a bit of sly commentary, and that felt like exactly what we should be doing.

—Alexandra Napier

__________________________________________________________________________________

Andros, November 25th

Hi Jonathan, so maybe we can start here—in your keynote address for the Postdance Conference at MDT in Stockholm you said, “History is a straight line but my body disagrees…” and I was reminded of when I heard the composer Alain Franco say in a talk that, “The arrow of time is floppy. Its a floppy arrow.” At least since Einstein, this has been a tenet of physics, but your talk brings this notion to the subjective level of how we experience time, and as dancers how we experience the non-linearity of time so concretely within our bodies. I’m interested in this notion and why or how it might be of particular relevance today.

Jonathan, December 1st

Hi Andros, I guess much of what I meant by trying to write as though my body was talking in that keynote address, was a kind of rhetorical attempt to deal with the impossible and unsustainable pressure on us all to produce the new. I mean I think it’s more complicated than just asking my body, but it seemed like a good place to start thinking about what people mean when they talk about newness, and how it may or may not relate to what we experience physically when we work. And I suppose it’s particularly complicated as a dancer since you can’t just shrug off what you already learned and absorbed, because motor memory is so durable. So we end up all the time trying to recontextualise this growing mass of unerasable information, and I wonder sometimes if it’s something I’d be better off trying to work with, rather than resisting.

And the other thing I found myself wondering about is how my physical memory has a slightly different picture of dance history than the various versions of it that have developed in academia or art discourse, and how all the various physical and conceptual informations I have from all the dance classes and workshops I did and performances I saw, are related in much more complex and lively ways than the historical canon allows. And this codification of the historical canon becomes a way to marginalise artists who don’t quite fit in, which is a shame because for many of us our most treasured memories of performance are delightfully obscure and unexpected, and that’s why we love performance as opposed to iconic recordings of great works. So for me this is important for the future, because the only way we can deal with the proliferation of dance and performance work and the way we feel overwhelmed, is to tell each other what we see and why we think it’s important, and take the responsibility out of the hands of experts and keep the thing alive by loving it, in all its forms. And this means finding new ways to relate what we see to what has come before, and the context we find ourselves in now.

Andros, December 1st

What this implies for me is developing a particular relationship with the notion of progress. I mean that recognizing one’s doubt about what you say—the impossible and unsustainable pressure to produce the new—isn’t a problem only for our field, but I think it has particular implications for us. For awhile in the late 90s-mid 2000s I felt like every third performance I saw worked with dance citation. It was as if appropriation became a way to deal with that ‘mass of unerasable information’ stored in the body. But citation now feels like it carries a slightly cynical tone to it. And yet creating anew, continually, once or twice a year reawakens doubt and even dread. So this is where I bring up the notion of progress, and developing a particular relationship to it, because it seems to me that we don’t feel like we can keep going forward the way we’ve been, and yet, we can’t either go backwards. That seems to be the impossibility, and I agree with you that this is only made worse by a relationship to history which only includes The Great, Dead Ones, whereas we as practitioners have all of this often not so great, sometimes pretty bad, but nevertheless living work inside us.

Currently, I find myself asking how I can do both—how can I create a kind of blur between past and future, speeding up and slowing down, going backwards and forwards simultaneously- and how that might develop my relationship to the notion of progress. History has a tendency to objectify the past and to expect artists to perpetually break from it in the pursuit of the perpetual new. Whereas I think performance is uniquely suited to contest that notion—rather to activate the future ‘past-ing’ and the past ‘future-ing’. It’s like you say in your address, that there’s no use disentangling Trisha Brown from Michael Jackson. History is the act of disentangling, but I think we’re uniquely suited in this medium to develop this entanglement, to express how non-linear history really is.

Jonathan, December 2nd

Ok, well I see I was using my nice short poetic sentences in the keynote address to try and avoid tying myself and anyone else in too many knots, but you’re going there so let’s see what happens. I know what’s on the tip of my tongue but I can’t guarantee it’ll make total sense. And it doesn’t help that I’m stuck in one of those familiar dance situations, where I’ve been given a nice apartment in the building where I’m working and everyone has gone home and I’m left alone on the top floor of this totally empty block, in a city I don’t know, and I’m lying here listening to the noises below and trying to distract myself by thinking about what you wrote.

And between bouts of hoping I’ve finally fallen asleep, these thoughts keep going round in my head about body memory and practice and what it means to be contemporary. And it seems what we’re dealing with here is a question about who owns the contemporary, and the fact that at the moment it’s in the hands of a very small coterie of visual arts players and magazines and other media that follow their lead. And this particular viewpoint still produces great work, and I like the surface feeling of it, which is familiar and comforting and makes me feel alive. On the other hand I notice a lot of the performances I see and love are in contradiction to this limited view, and yet they feel no less current. And of course the danger of the international visual arts contemporary is that it excludes so much in the world which is also happening.

The critique usually levelled at things which aren’t thought to be contemporary enough, is that they’re caught up with things that belong too much to a nostalgic past, or to a past compromised by power games of one kind or another, which past must be critiqued for all sorts of good reasons. So the ‘dance citation’ you mention, which was endemic at one point, was a way of trying to allow the past and at the same time critique it. The thing is though, that it’s not so easy with muscle memory, because the old stuff hangs around whether you critique it or not, so you end up in a constant negotiation and eventually you have to treat it as though it is contemporary. And my experience is that when something comes out from stored pattern like that, it doesn’t feel nostalgic at all and its politics have shifted.

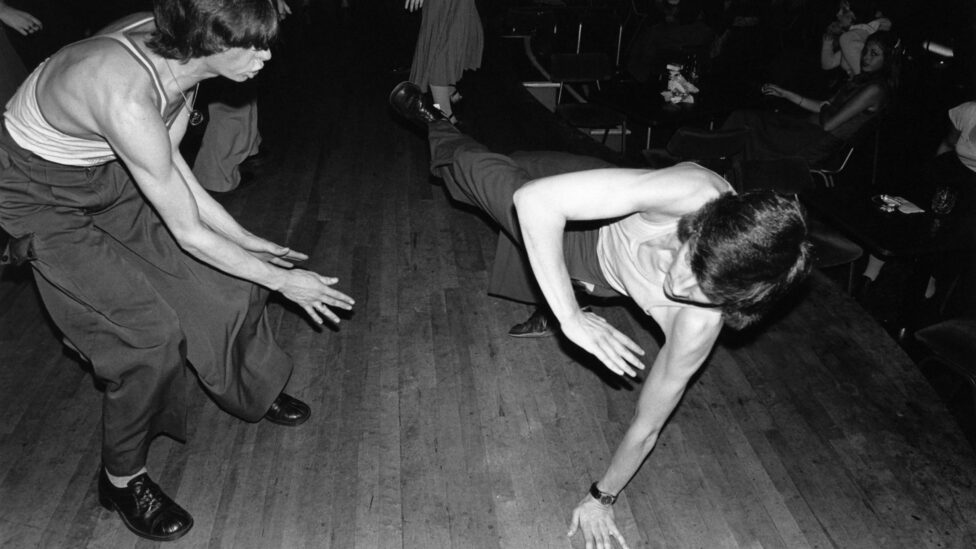

And muscle memory comes from us repeating stuff when we’re learning it, which used to be called craft but now we call it practice, and we’ve kept a low profile about it recently given how it doesn’t fit in with how the visual artists are working. Which is why hip hop is so important, because the flip side of me commenting in my keynote that hip hop has turned virtuosity into a political act, is that meanwhile we’ve been thinking virtuosity is bourgeois, and that paradox bears some thinking about.

Andros, December 3rd

Well, then let’s get knotty! I think you’re right to ask who owns the contemporary—the contemporary is a currency like any other, filled with all kinds of politics, hegemonies, ideologies, and as long as performance fails to express itself as necessary to a market driven, object driven culture, well we know how the story goes. But the other side of it is that as soon as performance succeeds to make itself necessary to that culture, we also know how the story goes. For me, dance’s currency is that it’s both not at all contemporary and hyper-contemporary at the same time. Again, it goes forwards and backwards at once. Backwards because watching something (usually) from one perspective over (usually) a pre-determined period of time, while (usually) being rendered immobile and unable to use that which you are consuming whenever you want is really not contemporary! Forwards because we’re experienced enough consumers to know how utterly disappointing objects are in terms of actually effecting change in our lives, and in this advanced consumerist economy, experiences become increasingly important, especially because of their potential to allow access but resist consumption.

You talk about hip hop as turning virtuosity into a political act, and in your talk you also mention how it’s found its way into our collective motor memory. Am I being over-optimistic to say that contemporary dance has found its way into the collective motor memory of museums, galleries, and the visual arts in general? The two most interesting shows I saw last year in museums were the Pierre Huyghe show at Centre Pompidou and the Philippe Parreno show at Palais de Tokyo, and I couldn’t help thinking that they both operated like a dance. To instigate a choreographic sense of time into the exhibition space seems to me as potent as what hip hop has instigated in contemporary dance. Since hip-hop, we can’t ignore the possibility for the body to get down anymore- not up in the balletic/ modernist sense, but down. And I think since contemporary dance, contemporary art can’t anymore ignore event, movement and time.

Jonathan, December 4th

I’m wondering what anyone else who reads this might be thinking about the way performance and dance has become a little bit special at the moment in the visual arts, but I have my doubts about the claims made for it. And funnily enough when I allow myself to think, well hang on a minute is performance really resisting consumerism, then I feel a bit of relief from the pressure. I mean I can see why performance might resist the saleability of an object, but this guilt trip from the visual arts about their own greediness isn’t really our problem, and we’re not here to solve it for them. And anyway I don’t want to get too excited because they’ll move on pretty soon, and we can get back to being the extremely potential but ever so slightly left field joy that we are.

But yes, I do get the thing that it’s always seeming pretty down what it is we’re doing, and I mean any kind of intelligent performance in general, like including the lady I heard last week singing unaccompanied English folk songs to twenty people in the upstairs room of a pub.

And fuelled by my fury in the wake of the English Parliament deciding to bomb Syria, I’m tempted to leap to the idea that performance is so great because it’s always proposing what in Quaker parlance is called ‘getting a feel for the sense of the meeting’. And this taking the the temperature of the room is not about conventional democratic consensus, but about a space where you wait and see what might be happening. And of course it requires that we all deal nicely with our egos and problems, and sometimes we manage that and sometimes we don’t. And this delicate act of self-surrender is required of us whether we are a performer or spectator, in a theatre or a gallery space, which is why what we do remains a such potent tool.

Hip hop virtuosity is so great because in the battle egos are running high, but it’s tempered all the time by wit. And at the end of the day everyone shakes each other’s hands, arriving and leaving the room. And the philosophy is each one teach one, no leaders, just everyone getting a sense of the feeling of the room. I mean we have this to offer, in our practice as much as in our performances. And it feels pretty necessary, whether or not you call it contemporary. And it’s not an idealistic place and it doesn’t always happen. Something like that. It isn’t an idealistic place and it doesn’t disclude any amount of critique.

Andros, December 4th

Performance resisting consumerism is like the Polish joke (maybe I can get away with publicly telling it because I’m half Polish) about the group of Native Americans who capture an American, a something or other, and a Pole, and grab them one by one and start carving them up into canoes. Then suddenly, the Pole grabs a knife from one of his captors and starts poking holes in himself. When the chief asks him, ‘what the hell are you doing??’, the Pole responds, “Well, no one’s gonna make a canoe outta me!” No one’s gonna make a canoe out of dance, and we’ve made sure of it.

For a long time there wasn’t a discussion about dance that didn’t eventually turn around to comparing dance in Europe versus dance in the States, and now its dance in the theater versus dance in the museum and either way, the conversation tends to revolve around a dynamic of a certain success marked by a certain suspicion. Maybe we don’t want to see anyone else getting made into a canoe.

But I want to make a link between two aspects of what you’ve been speaking about—on the one hand you asked ‘who owns the contemporary?’ and we’ve been speaking about that in terms of the politics of how the contemporary is determined by certain social structures, but also in terms of bio-politics and what we do with ‘old fashioned’ muscle memory and what we feel are the limits of perpetually producing ‘the new’. On the other hand, you’ve brought up hip hop as an example quite a lot, which isn’t- at least in terms of dance- something I know a lot about, but it feels like from the way you refer to it, that there’s a kind of being ‘in-time’ which—if we can manage to not romanticize it—creates a culture of being in time together, ‘getting a feel for the sense of the meeting’ that you speak about. And this being in time together is what I’d say we lack most, even in this time-based art form. Being in time together is different than perpetually trying to create the new, but its this perpetual attempt—or what Hartmut Rosa calls a ‘frenetic standstill’ that I think disables us from being in time together, to create a culture rather than constantly attempt to out do, break, or de-territorialize it. I think the real question is how, with all of these times that co-exist in our bodies, and all of these differences of time both in terms of fragmented schedules, and different experienced histories, can we come together and be in time together, is there anymore a context where that can take place without going backwards to dogmatic movement languages. It seems like with the example you give of hip hop has the confluence of feeling contemporary but still sharing a language. This sharing a language is rarely considered contemporary and yet it seems its also what forbids us from being contemporary- in the sense of contemporaneous- in the same time together.

Jonathan, December 6th

Well you put your finger on something there, that the idea of ‘the contemporary’ in dance until quite recently meant a certain shared language or style of doing things, and this style changed a bit over the years from modern shapes to flowing shapes, but it was recognisable and it was a resource we had in common. Now however, there’s a sense that conceptualism has shifted attention from style to concept, and in many ways that should open up possibilities but it doesn’t feel we’re quite there yet, because we end up adrift in a sea of possibilities that don’t quite convince us. It’s something to do with the way danced materials carry more sense of authority, meaning and emotional weight when the history behind them is understood and absorbed by the dancer. And although I can think of plenty of reasons to question authority, meaning and emotional weight, nevertheless we all love to watch a flamenco dancer, or a Northern Soul dancer, or Carlos Acosta.

For me the big revolution recently has been the development of ideas around dramaturgy, which gives a new way of looking at the weight of all the elements in a dance performance, and trying to get to the heart of them without losing or confusing either the dancer or the viewer. And really great dramaturgy allows us to work through all this messy entanglement of bodily experience, and keep fluid in time, and see subjective and objective viewpoints. The only thing is I could wish for a better word, that maybe didn’t rely on ‘drama’ quite so much.

And Northern Soul by the way, for those of you in America who might not have heard of it, is a strange hybrid Northern English dance form coming out of the late 1960s, that took obscure Motown era tracks and invented an almost pre-breaking, spinning, floor hopping dance to it. And the Mecca of Northern Soul was a dour town called Wigan where all-nighters were held at a building called the Wigan Casino. And Wigan casino has now been knocked down by the town fathers who somehow felt threatened by it, but the dance itself is still revered.

Andros, December 6th

First of all, Carlos Acosta was in my dream last night, no joke and this morning I was saying to my partner, that Cuban ballet dancer I was once mistaken for in London was in my dream, Carlos something or other, but I couldn’t remember… and a few hours later, here he is again with an encore. Well done, Carlos.

I really like this back and forth because I don’t think we’re ever really in agreement or even talking about exactly the same things—our references are really different and our responses seem continually tangential to one another, but at the same time I feel like we’re trying to retrospectively construct a maze that we’ve already passed through, even if not through the same pathways. And yet its hard to retrace the steps because the lines have all almost disappeared already. So we say, I think it went like this, or I think the problem that we solved or the dead end we hit went like that—and ultimately it feels like retracing this maze is a lot about looking for an ethics of how to move forwards. We’ve retraced the steps of the problems of perpetuating the exhaustion of the new, and the problems of the aesthetic regimes and authority of the old. But we know that despite its ever-shortening shelf-life, the new is important and that with all of its past expiration datedness, the old offers us languages that we no longer would permit decades to construct anymore. And somewhere in there, I think there is an ethics for how to move forwards.

A dramaturge for me is kind of political representative for the public, and like a politician should both represent what the public wants, but not only what the public wants, also what she thinks is good for the public- and here ethics becomes extremely important. Producers, dramaturges, and authors often get caught up in the first part—of what is expected the public wants, but in my experience the public doesn’t usually want what it thinks it wants, certainly not what we think it wants. This is often misunderstood by chasing the new, where we get into a rush but never really move anywhere—again, a frenetic standstill—to constantly arrive at the incrementally new that we’re sacrificing our prospects of a future for. And we do arrive there, there are good pieces that arrive at the new all of the time, so frequently perhaps that we barely get to experience it as new. But I think its actually like you say in your keynote, the best pieces never quite arrive.

Jonathan, December 9th

Ha, I’d forgotten that time in London when you were mistaken for Carlos Acosta. It was when we were remaking The Stop Quartet and I asked you’d if you’d do a slightly weird part where someone has to wait for 40 minutes and then come on for the last 5 minutes, and at the dress rehearsal you never came on at all because you were busy washing your hair, which still makes me laugh. The performance that never quite arrived. And yes, it’s odd I hadn’t pictured the dramaturge as someone who mediates the desire of the audience member. I was talking more about the dramaturge as the person who tries to sense how clear the information is, between the muddled desires of the maker and the unsuspecting spectator. But I like your call for a space of non-mediation, or non-manipulation. I immediately want to know what might happen there. And it comes back to that image of a conversation which doesn’t seek ready agreement but rather listens and leaves things hanging, and somewhere in the gap between thoughts something happens that might point us forwards, or sideways or whatever. And the paradox is that you ended this conversation brilliantly with your final line about pieces that never quite arrive, but I couldn’t stop myself from saying something else and now we’ve really got a conversation that never quite arrives, but rather leaves things hanging. Like this. With thanks and praises.

Jonathan Burrows danced with the Royal Ballet for 13 years before leaving to pursue his own choreography. His main focus now is an ongoing body of work with the composer Matteo Fargion. The two men are co-produced by Kaaitheater Brussels, PACT Zollverein Essen, Sadler’s Wells Theatre London and BIT Teatergarasjen Bergen, and are currently in-house artists at the Nightingale Brighton. Other high profile commissions include work for for Sylvie Guillem, Forsythe’s Ballett Frankfurt and the National Theatre, London. Burrows has been an Associate Artist at Kunstencentrum Vooruit in Gent, Belgium, London’s South Bank Centre and Kaaitheater Brussels. He is a visiting member of faculty at P.A.R.T.S Brussels and has also been Guest Professor at universities in Berlin, Gent, Giessen, Hamburg and London. ‘A Choreographer’s Handbook’ has sold over 8,000 copies since its publication in 2010, and is available from Routledge Publishing.

Andros Zins-Browne (New York City, 1981) is an American choreographer who lives and works in Brussels. His work consists of “dance performances and hybrid environments at the intersection between installation, performance and conceptual dance, performed by a mix of professional dancers and amateurs. They explore the way in which the human body, movement and matter can interact until a certain melting point is reached and the diverse media appear to take on each other’s properties.” (Catalogue from Beyond Imagination, Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam)

Andros began studying ballet at an early age at the Joffrey Ballet School in New York City. After completing a degree in Art Semiotics at Brown University (US, 1998-2002), he moved to Brussels in 2002 to study at the Performing Arts Research and Training Studios, P.A.R.T.S (BE, 2002-2006). He later pursued a research program in the Fine Arts department at the Jan van Eyck Academie, Maastricht (NL, 2010-2011).

As a performer, he has worked with Jonathan Burrows, Mette Ingvartsen, Tino Sehgal, and Maria Hassabi.

In his own creations, Andros has collaborated with several visual artists, often using the stage as an installation space. He has also created two performances where the dancer is presented as a hologram.

Andros’ works have been presented internationally including the Centre Pompidou in Paris, Dance Umbrella and the ICA in London, Het Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam, HAU in Berlin, De Singel in Antwerp, Vooruit in Gent, Next Festival in Kortrijk, MDT in Stockholm, Kaaitheater in Brussels and the Theater Festival Impulse, Düsseldorf where he received the Goethe Institute Award in 2011 for The Host.

His last group performance, The Middle Ages premiered at Vooruit in Gent in March, 2015. Currently he is working on Atlas Revisited, a collaboration with visual artist Karthik Pandian in which the two artists have been attempting to choreograph a group of camels to dance a performance by Merce Cunningham. Atlas Revisited will premiere in April 2016 at the Experimental Media and Performing Arts Center (EMPAC) in Troy, New York.

Andros is an associated artist with Hiros, a management company in Brussels. In 2013 he founded his own association, The Great Indoors.