Deborah Hay began the Trio Commissioning Project in 2023 when she invited twelve dancers who had touched her practice and assembled them into four trios that would re-adapt a score from the earlier Solo Performance Commissioning Project. Tasked with raising the $10,000 commissioning fee, each trio traveled to Austin or Bennington College to be coached by Deborah for two weeks and then were at liberty to continue developing then performing the score, making their own decisions about production and performance elements like lights, costumes, and sound as as well as space “(more or less),” and time.

Each reporting from distinct trios at various stages of development, Amelia Heintzelman, Jeanine Durning, and Christopher Roman converged virtually last month to reflect on their experience as part of the project. Contemplating the radicality and reality of the project and their ongoing histories with Deborah, they explore the ethics and aesthetics of dis-attachment, shared authorship, and the mutability of the archive.

I like to think of their conversation as another, reassembled, trio – a choreography that renews the question of three in both its subject and form. Moving through, and with, the rhythms of difference and alignment, together they reanimate what Deborah calls the “practical magic of the trio” and, in the end, the unknowability of dancing.

—Tess Michaelson, CC Guest Editor

This article has been edited for the purpose of publication.

Amelia Heintzelman

Have you two met or worked together before?

Jeanine Durning

Well, I’ve admired Christopher as an artist in Bill Forsythe’s company, and I have seen him perform many times over the years. I’ve had very memorable experiences as an audience member and then we got to know each other through Deborah’s work.

Christopher Roman

I think that that’s really important to this conversation, too: how we overlap, how we meet, how we admire, how we cross-pollinate. I first saw Jeanine in “If I Sing to You” as part of William Forsythe’s invitation to Deborah. He brought them to perform in Dresden. I had seen one other piece of Deborah’s before, but that piece, in that setting and at that moment, shocked me so deeply on so many levels.

And then this Motion Bank project from William Forsyth’s initiative started, and Deborah was invited to be one of the artists revealing elements of their choreographic process. That’s when I had the chance to work with Deborah, just for a little bit, until she made decisions to really bring in people that had a direct and long-standing experience with her work, to have that choreographic process more fully expressed and documented. That’s when I got to know Jeanine and Ros Warby and Juliette Mapp a little bit more. Then I did a Solo Commissioning Project, and I got more in line with Deborah’s work, and I commissioned one of Deborah’s pieces for Motion Bank at one of my festivals that I brought Jeanine and Ros to perform in.

Then we danced together in “Tenacity of Space” for Dance On. Jeanine was rehearsal director for that after Deborah left, and then eventually, on a couple of tours, she joined us as a cast member. Then, as part of Tanz im August retrospective, Deborah wanted to make a new piece as the jumping off point to go retrospectively, and then work backwards to reveal her process. And we did a piece that I produced for and with Deborah, called “Animals on the Beach,” with Jeanine, Ros, a collaborator named Vera Nevanlinna, and Tilman O’Donnell.

AH

So much history.

CR

Yeah, so much history.

JD

Yeah. What’s your history? You have a more recent history with Deborah.

AH

I met Deborah in 2019 at Atlantic Center for the Arts, a residency where you study under a master artist alongside a group of other artists. As a cohort, we decided to all do a morning practice that Deborah guided. She was in residence with Eva Mohn, so after the morning practice we would watch her rehearse.

That time was very impressionable to me. Deborah was using questions and coaching with a very specific use of language. I was very porous, naive, and impressionable. This time with Deborah really changed me, helped me understand what it is that dancers do when they go to the studio, what keeps them going back.

JD

Do you remember what the questions were or the language she was using?

AH

“What if where I am is what I need?”

“Be a pig”

“My whole body at once.”

I don’t know if any of those are questions, but these are what she was using. When I worked with her most recently in Austin for the Trio Commissioning Project, she was saying she’s moved on from using the questions.

JD

Yeah, she doesn’t use questions anymore. And she rarely uses these phrases that have become so a part of her lexicon, which is also, I feel, very typical of Deborah: she’s willing to just continue to move on in her work, rather than hold on to what it has become which is fundamentally radical, I think. She’s a true artist in that she’s never really holding on. Principally, the dis-attachment aspect which is such a fundamental aspect of her work, is also something that she’s living in her artistic process. It’s playful for her, I think.

This thing you say, Amelia, about this naivete, I think that’s maybe a more helpful way to go into her work. There’s this sense of wonder, this sense of unknowability or impossible possibility. There’s no one way to do it or to comprehend it or understand it. And even with My Body, The Buddhist, it’s not Deborah the Buddhist, it’s my body the Buddhist, which is inherently trusting the incredible intelligence of the body that’s beyond the ego, who says I can creatively master all these complexities. So, I think being creatively naive is very useful and opens up more possibilities.

CR

I thought that as well when you said that, Amelia, and when you said something about going to Atlantic and being at once student and artist – and maybe student’s not the right word at this point in our group – but I do feel very much on an equal level with Deborah. Even though in the end it is credited as Deborah’s work, I do feel wholly collaborative as a co-choreographer, as an artist. We, day by day, through the practice, end up influencing how Deborah’s able to see things, and now we’re seeing and experiencing it from the inside.

AH

Yeah, there’s an autonomy that’s required when you’re working with her, taking on the responsibility of answering the questions or interpreting the coaching so it serves you, using the audience and your seeing in a way that serves you. You have to care for the work, be very present with it. It’s challenging, but also so rich. It’s knowing that I’m holding so much as opposed to just fulfilling a task, that I’m questioning the task and I’m defining what the task is while I’m also doing it.

CR

But also letting go at the same time.

AH

I know. And also un-knowing it.

JD

I do think there is this radical trust Deborah has in the agency of the performer, and that choreography, on some level, is the act of the dancer in the unfolding moments of practicing performance. The choreography is not something outside of that experience; it is the experience of the dancer. I think there is both responsibility, care, and also a deep kind of inquiry that is required.

CR

She is more contemporary than anything that I’ve seen that is claiming to be of the now, and this contract that we have with one another is just from my experience anomalous. It just doesn’t exist, that trust in us, beyond the collaboration, that we take it over to produce it the way that we wish – of course, within the understanding of Deborah’s work. I come from a very institutional way of thinking in dance that has never given me that kind of permission or space to be recognized as co-author of something. There is so much room for me to be seen, not just in a spotlight or acknowledgement and crediting way, but just as my contribution as a dancer. It was almost like an emancipation in a sense, being able to work with her and be in dialogue with the things that she’s been in dialogue with herself for decades.

Over the course of many years, you start to come to understand that your authorship, or that your responses, specifically your own understanding that everyone else has their responses as well, become intrinsic and valuable to the whole of the legacy. Maybe I’ll find better words to say it better in the future, but it’s the thing that continues to gob smack me: this person still is Deborah Hay, a name, but I feel very much Christopher Roman within the exchange, and that’s hard to come by in dialogue with a choreographer.

AH

This type of working has allowed me to have a little bit more curiosity about what my role is as the dancer. Yes, I’m an interpreter, but I also can be deviant. I also can rebel, or I can be subservient, or I can look for clarity. There’s so many different ways in which we answer or respond to directions. And there’s a lot of power in that role; it’s exciting within the context of what Deborah asks us to do. You have space to be curious; it’s not like anything goes, but it allows you to understand your range.

JD

Or what your priorities are as a performer.

AH

Yeah, they light up in a way that teaches me.

JD

Even the insecurities as well because I think sometimes the resistances can be a way of bolstering yourself against the unknowability of it. There’s something about that that’s interesting in her work, that it’s constantly confronting oneself in relationship to their own practice, and what those sets of confrontations might be on any given day or in relationship to your history as a dancer and the expectations that you might have of yourself in relationship to performing.

It’s interesting this thing of interpretation. It’s an interesting term. I remember I was learning a solo called “No Time to Fly,” which then became a trio and then a duet called “As Holy Sites Go,” and each of us, Juliette, myself, and Ros, were given the script for “No Time to Fly,” and we each learned the choreography from the script based on our own practice of Deborah’s work. And I remember reading the script and being like, Ooh, I could do this, and I could do that, and I could go in this way and start to kind of compose it, you know? And I was really just so pleased with myself that I had all of these amazing, creative ideas, and I wrote her and I was like, The beginning could be this and it could be that and I imagine it this way and I could interpret it in this way, and she wrote back in her typically concise way: What you could interpret and imagine is too limited. And it fucked me up. In the best way. It made me realize: Oh, I have been going about this the entirely wrong way. I have to practice. I have to go in daily practice and my body is going to teach me how to do this work. It was a reminder, what are you going to come back to? It’s not your idea, it’s your practice. And that was just such an amazing learning experience.

AH

Just another example of her being like, the knowing is a trap…

CR

Maybe that’s a good segue to talk about this radicality of Deborah and about, especially in this environment currently, about what it is to be invited to commission something and to have it divided by three people. We’re three artists of now, in now, and we’ve got to talk about that element of it that is tricky. To come up with that kind of money and then hope after we’ve learned it and found the kinds of funds to try and produce it, with Deborah’s entire history at the helm, has required a lot of funding and management. In this landscape, that’s just not so easy to come by. It says something about the field of dance and how we’re being asked to shape-shift to fit into surviving as artists – how that’s just changed radically in the last decade.

AH

In this configuration – three people sharing responsibility for one work that is simultaneously owned by them and also possessionless – there’s this amorphous, constant motion and reconfiguration; stepping in and out of responsibilities, stepping up to the task then stepping down when it’s become too much. A lot of butting up against. On a theoretical level, it’s like, Oh, that’s interesting. That’s a dance. That’s nonhierarchical, and I can get behind that. But then when you’re on the ground doing it, it’s so counter to all the ways that we live as people who have to exist in the world and participate in culture. And so, of course, it feels horrible, awful, impossible. And also, dance does the impossible again and again.

Right now, I’m in a moment of questioning where the project sits as a piece of dance history, an archive of my relationship to Deborah and her influence on me. Especially as someone younger who doesn’t have a prolonged history working with her, The Trio Commissioning Project felt like a seed that I’m now responsible for planting, watching it grow, watering and caring for it as I choose.

JD

I think going into this endeavor, to be honest, I wasn’t even thinking of the production of it. I was really thinking, after years of working with Deborah in different capacities, and then the last few years working as a director of her work as a coach and a rehearsal director for Cullberg, I wanted to go back into my own practice to see how the dissemination, the pedagogical relationship to her work changed my practice of her work.

I do think that Deborah’s work lives in the practice of performance. I think that that is where her work meets the edge of knowability and, as she would say, catastrophic acts of loss of self. So, I do think that that’s where her work lives best. But, I also feel – not to mythologize it so much – but to humble myself in continuing to learn from her, and learn from her in this stage of her career where she’s really dis-attaching from so much of her own personal tricks and devices. I feel very privileged to be a part of that history, the line of it, the lineage of it, and to share in that.

AH

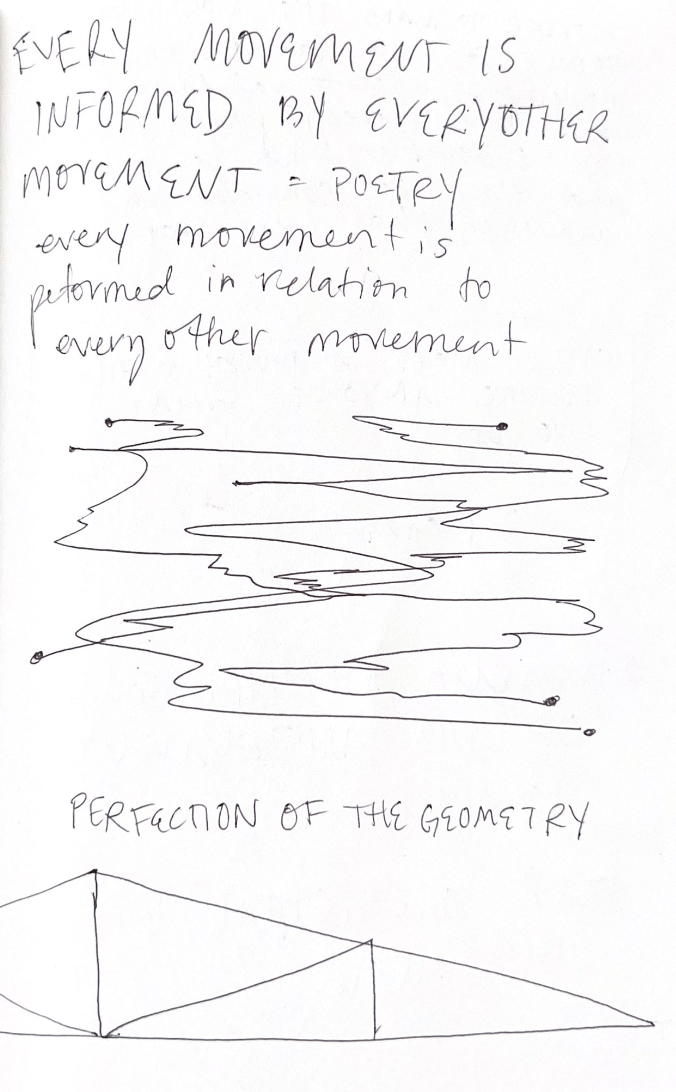

The one thing I feel like we haven’t talked so much about is the trio, the practical magic, the geometry of the number three.

I wonder if the practical aspect is about reworking and revising, that constant paying attention that is practical. This level of attentiveness allows for the work’s unfolding, it creates scenarios that are beyond any one performer’s capabilities. For me, in this process, the practical magic of the trio was both a tether and a source of tension my group was constantly contending with.

JD

Yeah, noticing the geometry unfolding, which is both understanding composition as it’s unfolding, but it’s also, I think, particularly in my understanding of her work as it is now, there really is this communion with all that there is. There’s teaching yourself to see smaller and smaller particles, teaching yourself to be in relationship to the universe. How you are served by how you see and by presuming that you are seeing the perfection of the geometry, rather than searching for it or trying to make it happen.

Deborah’s relationship to space as a practice-based construct is getting larger and larger, where it used to be the studio as lab, and then it was the space, including what you see and can’t see, and now it’s the universe. It’s how to survive in the universe. Or, rather, it’s realizing we are like that single blade of grass that survives in a crack in the pavement precisely because it is a part of the universe. And whether or not you believe it is not so important. It’s important to keep in the dance. To keep the perception of these things at play, and how that perception feeds the dance as you continue to learn from the body.

Like Deborah says, you can’t think your way into it. I think the true unknowability of it is the magic-making of the proposition. But it’s important that it is not anything goes because the sharpening of your attention is really what produces the potential for that magic.