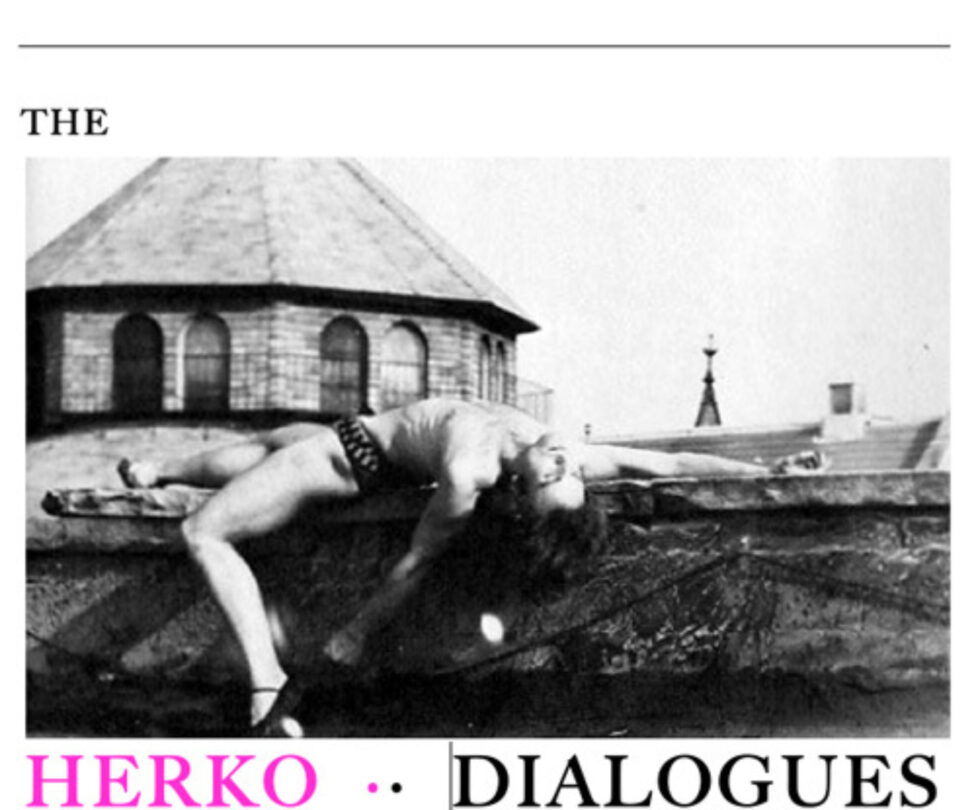

On October 27, 1964, Fred Herko, dancer, choreographer and founding member of Judson Dance Theater, leapt to his death from a fourth story window in the West Village, while listening to Mozart’s Requiem. Or perhaps it was another piece of music. And maybe it wasn’t the fourth floor. Beyond the fact of his suicide, and the presumption that is was staged and performed for an unwitting friend, there is much ambiguity around the circumstances of Herko’s death. And, for that matter, his life and works. Herko’s aesthetic entanglements were many—Judson, Andy Warhol, Jill Johnston and more. His dances have been described as campy, romantic, queer, lazy, incandescent, excessive and potentially leading his career nowhere. Or, maybe he knew exactly what he was doing.

In the ensuing five decades since his death, many in his Judson cohort have met with praise and, what is more, a secured place in dance history. Herko continues to flicker on the periphery, appearing in photographs or films, alone or with other eventual giants of Judson and Warhol’s Factory. Herko’s elusive status offers unexpected lines of thinking, radicalizing traditional ideas secured within historical narratives. Herko’s presence has embroidered the works of a handful of writers and historians, notably, the late performance scholar José Muñoz in his chapter devoted to Herko, entitled “A Jeté Out the Window,” housed within his text Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity. Muñoz engages Herko—and his suicide—as a choreographic figure whose movements respond to the contours of queer time, denaturalizing both the theatrical and the quotidian and inviting a kind of utopian performativity into the world. Walking the reader through a profound rumination on the limits of finitude, performance, queerness, utopia, labor and time, Muñoz, points out that this dancer’s final gesture of flight indicates apertures through which we might reflect on escapes from capitalist and historic oppression.

On October 25, 2014, almost exactly fifty years after Herko’s death, NYU’s department of Performance Studies, in tandem with the Tisch Institute for Creative Research, sponsored a one-day symposium called Fred Herko: A Crash Course. Taking as its premise the fact that no one is an expert on Herko, scholars and art historians presented their biographical research and thought experiments around Herko’s life, suicide and legacy. Critical Correspondence invited eight relative strangers: choreographers, performers, and scholars to attend the symposium and then pair off to reflect on how that day’s discussions about Fred Herko, José Muñoz, Judson and the 1960s coincide with their own artistic and intellectual practices, bodies, and politics today. The meanings of Fred Herko’s life, work and death, and whether such meanings can be consistently deployed, is a central question of THE HERKO DIALOGUES.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Adrienne Edwards: Maybe we could begin with initial reactions to the symposium? Because that is what we have been asked to discuss, right?

Jen Rosenblit: I think so, about the conversations, or whatever sorts of things were circling around surrounding our reading or thoughts on them.

AE: The first thing that came up for me, for better or worse, is this question that seemed to linger between what constitutes truth and history, versus interpretation —which seemed to be a kind of question of value. What I mean is, I’m going to forget his name—but the historian, the biographer (Gerard Ford) who José spoke to as part of his research for the chapter on Herko in Cruising Utopia—seem to put forward. He was insistent about a truthfulness that can be located in the archive, which seemed to be an overly valued estimation about what that archive can hold and therefore what it can do with a certitude that what is located there can be trusted. This was particularly evident in the instances when as he went through his talk and said, “and this person is here, and so in so is in this room” to make a claim, it seemed to me, which I really wanted to trouble or think through or see if you had also noticed this desire for certitude. Then, especially revealing was the last part of the conversation, when there was a dialogue between all the participants in a round table wrap up, there was a kind of sparring around the fact that interpretation is somehow inherently suspect, somehow impermissible and inadequate. And so I was thinking about this from the vantage of my work as a curator, or particularly in relation to my work as a writer and scholar with a particular understanding of where I tend to fall in relation to those kinds of unfortunate binaries. Then I was thinking about it in relation to your work as a dancer, your process and what you value in your work. This question of memory, this question of truth, this question of what does one have permission to do, and the question of how does one interpret. How do you think about interpretation in relation to embodiment? Or working with the body as a tool?

JR: We tend to talk about embodiment in the dance community in a certain way, as though it has to be achieved. It is as if you’re not actually doing the ‘right’ thing unless you’re embodied. I often believe that even though it sometimes feels problematic and like another kind of systemic virtuosity that I tend to shift away from, when I am not so interested in something performance- or practice-wise it is often that I’m seeing a carving of something or a shell of something but it might not feel embodied in this thrusted way. So, I’m waiting for that moment because there is a transcendence that happens when the body is working on the idea versus the idea sort of sitting in a book, or on a shelf, or in the studio. I think it’s about being seen, having audience. This is when the question of permission or interpretation comes into play. I’m going to go on a little tangent here, it’s not directly related to Herko but more to things that I am thinking about now in my own process that feels aligned with how I am relating to this conversation. I don’t know if my research is giving me permission or access to certain cultural or communal knowledge bases (if that is what we mean in terms of permission), but I definitely feel a crack or an opening inside the landscape of ‘yes’ and ‘no’, allowed and not allowed.

I’m curious about the consideration of physical matter as a source and substance, of bodies as matter, objects as matter, space as matter, a room as matter and audience as matter. All of the things involved in witnessing and seeing and being seen are sort of participants in this way that is really hard to negotiate and even harder to craft, especially in that singular moment when the audience comes in as the final participant. Considering matter seems to challenge the final nature of that moment, it seems to speak to a multiplicity of moments. Even with Herko, this being seen thing comes so far after his death and, still, questions of right story or wrong fact seem to be important. Knowing what happened, being clued into the cultural moment seems to give us some truth that can reflect back on where we are now. This concept of matter—to start to place a value and an importance on everything as body – seems to create spaces around truth or rightness that allow for that transcendence that I know exists with a relationship to embodiment. If I have an object that I’m working with like a lemon tree, it is either a prop or an object that’s a little lesser than the equivalent to my body, inside of the framework of me making performance. I could also consider it in this excessive way as an extension of my body and so I don’t have to dance with it or even touch it to enact or embody that relationship. The consideration of it as substance and nonhuman body is an interesting place to start thinking about relationships both inside of the work itself and to the people seeing it. This exchange or relationship is directly when problems occur. People see things and either permission is granted or not.

AE: How do you think your work is perceived? And then I would like you to think about your work in relation to perhaps how Herko’s was perceived.

JR: My work is received with a lot of questions because I think I also put it out with a lot of questions.

AE: What sort of questions?

JR: Questions like, what does it take to come together? Heather Love spoke to the dystopia of coming together, this is a real question for me. How do we not idealize and create a situation where every time you see an arranged thing there’s an assumption that it’s going to feel good and right and look good and be its whole self? But there’s actually a crack in that system, that coming together for me, I have questions around it. How do we come together? How do we organize information? Is it always about assimilation? I feel like there’s something that happens when things come together, especially relationships between people that is about ‘let’s become one.’

AE: Some kind of conflation, or a tendency towards a kind of reduction. Do you feel that in your dances sometimes there is a perception, which conflates a dance into a common denominator of ‘these things in relation to each other mean x’?

JR: Yes, meaning is always at the center. It’s not anti-meaning or a lack of meaning but I think there’s a value system and a tone of that value. Meaning is not always on the top of my agenda. It exists and I don’t deny its existence and sometimes I operate inside of it. Sometimes I capitalize on meaning, on inherent meaning, and sometimes I’m trying to poke fun at inherent meaning. That’s what my last work, a Natural dance, was working inside of. Two male bodies stand next each other and if you squint their similarities blend and they look the same and that’s really problematic. People commented on their brotherness or their sameness, when really they look nothing alike. What is seen is a kind of shell—brown skin, dark hair, light facial hair, masculine gender—that can also be sensitive and soft. We talked a lot about the permission I had to box this, to frame them. It’s not like permission was ever granted to do so, and it’s not like they didn’t have problems with the questions that were coming up. I had problems with the questions that were coming up. Based on what my work leans toward or shows, people think “Oh, Jen thinks they look the same. Jen thinks they look like brothers because she put them together and they look like brothers.” There’s ultimately always a relationship to me, my views, beliefs, politics and my work and I wouldn’t want it any other way. It does limit a kind of permission in the work however. I am only allowed to explore things I believe in or ways in which I want to represent myself and others. It is another problem in performance and the body relating to other bodies that I am deeply interested in. The way that I craft work is bound to my politics but I’m not always enacting them or reproducing them with dancing bodies. Maybe I’m trying to push them a little bit with the dancing body, but not reproduce them. Then—you were saying in relation to Herko’s work?

AE: Yes. Do your remember Gerard going through the various interpretations, recollections about Herko’s personality? The question of who is this person illumines a yearning for a kind of biographical knowledge and desire to continue to circulate it. I think that there was all of this inconsistency around that and I was thinking about Paxton’s reaction to Herko’s work, specifically when he said “It’s not my thing”, meaning that it was campy, that Judson was a space, a sensibility that was about a particular kind of aesthetic—minimalist, for example. The understanding was that a minimalist aesthetic meant only certain kinds of movements were acceptable. So, what is it that this queer presence in that context is doing? How is it disrupting, not even disrupting, but playing into a certain kind of factor of significance? For me, this signifies something. Herko was just being in his own world in a particular kind of way, which leads me to wonder what exactly is excess? What is impermissible (as we discussed in relation to Herko’s body holding space in a particular way)? I don’t know, perhaps you’ve already answered it.

JR: Certain people come to mind in my direct community, Greg Zucculo—I’m thinking that especially during this seminar, when there was a really sentimental nature of talking about Herko with the limited information that we have. Then, especially the older woman’s reaction of “I actually knew these people,” I just started thinking about people I know and how they may one day be retold and the sorrow in that.

AE: That was really sad.

JR: It is sad. You cannot retell someone’s life. Especially if the life is potentially wrapped up in, I won’t say lies, but in alternate realities.

AE: Because he was living in an alternate reality.

JR: And I’m sure not even just about drug use. This person was especially intelligent in terms of creative process but maybe, as the failed resumé on the cover of the program at NYU shows, not business savvy. Somehow, and this is likely due to his early death, he didn’t manage to position his living legacy like Yvonne Rainer or others who have made names for themselves and their accomplishments are my generation’s new standards. We know who these artists are. My generation feels like the grand child of this time, it is part of our embodied knowledge and so we’re also the same. We’re exactly the same. Greg Zucculo is this artist who will always be around and for most will always be too much. People will always cast him off as too much, then one day someone’s going to curate him and say “the too much-ness is just enough.” Then he will be written about. My concern is that the value is only extended in a post sensibility or economy. How do we support and value processes and lives that are deemed as off center, too much, queer. I’m also thinking about Walter Dundervill. His aesthethic contains a lot and I think there’s a precarious nature to some people who are really operating not just inside of the craft of the form, like a formalist approach to the medium, but people who are actually inside of performance in this multi-spectrum kind of way. I often find that that’s related to the nightlife scene, the queer scene, the gay scene. I might be trying to say that I don’t think Herko is especially special?

AE: You know, I credit choreographers like Ishmael Houston-Jones, perhaps one of the earliest people to meld club movements into the experimental downtown dance scene, which I would suggest has spawned the whole tradition that you’re talking about. How do all of these things fit together? I find it really interesting that he referenced “form” and then switched to “performance” and that performance somehow has the same kind of capaciousness, meaning an ability to take on all of these things in a way that form would not, I presume. Dance is this really specific particular thing. It has a certain set of presuppositions—it’s the body, it’s the body doing something whether still or moving —it has a set of parameters. Whereas performance seems to be more open…

JR: I think this is probably going to sound confusing but I qualify form as something that has an audience, and performance doesn’t always. This is the whole glorious debate around Herko’s final performance that only one person saw. I think there’s such a sentimental thing about that, who sees. And we know that the most transgressive performances have happened in subversive ways other than this staging and sitting way. I have no desire to think about if his suicide was performance or not, for me that’s not of interest.

AE: It’s irrelevant. I do think that in some ways that slippage has to do with an immediate knowledge of the most basic things we do, which we think are natural and in fact are not. They are all performances such as the way in which we inhabit our body, the way we figure out what it is that a body can do is deeply performative.

JR: Considering relations between people to me is deeply performative and at the center of my work.. What does it mean that we stand far apart? But really, what is this thing, this standing thing? Why are we doing this together? Or, why are we doing this together and there’s no togetherness? What bodies do best is relate or they don’t relate. This thing about form—I know this is a cup but it could be so many things or, the cup could be with that excess. And not just what else could it be—could it be a candle? Not “things” like other items, but it can hold so much information. Then when it gets an audience, the audience delineates its form based on what they see and what they don’t see and their cultural understanding of cup, or that particular kind of cup, of the aesthetic of that cup, what is around the cup. Whereas, especially in considering the cup as body or as matter or as substance, it performs, it sits still, it holds a space in the room.

AE: It’s back to the kind of slippage that you were doing around the word “matter.” I want to introduce a third way to think about matter in relation to your work: Is matter a thing? It’s a question of value. But it’s also mater without one of the “t’s. I have been thinking and writing a lot about what I am calling ornamental feminism, and I was reminded of it because we’re two women sitting here thinking about this idea of excess, which José actually writes about, though in relation to Herko through Ernst Bloch’s formulation of the ornament. Specifically, José was riffing off of Diana di Prima’s description of Herko’s dances as neoromantic, which he himself described as excessive, campy. However, his understanding of Bloch suggests that the ornamental is about more than aesthetics but also the promise of an elsewhere and elsewhen not bound by the norms of the present. How do you think about ornamentation in your work? How do you think about the way in which you play with that in terms of notions of femininity? My interest in it came from a critique that Angela Davis did of the Feminist movement in the 70s, when she wrote “the abstract negation of ‘femininity’ is embraced; attempts are made to demonstrate that women can be as non-emotional, reality-affirming and dominating as men are alleged to be. The model, however, is usually a concealed ‘masculine’ one.” Which is intriguing and I’m thinking of this notion in relation to artists like Lorraine O’Grady, Tracey Rose, Wangechi Mutu, Mickalene Thomas, and so on. Their works have the assertion of a certain kind of spectrum of womanness, even like vamping within what that is—of what that could be. So, I want to talk through with you, which is José’s assertion for a claim of value for excess.

JR: In the dance field there is a starting place that is simple, clear, clean, efficient, thin and white. It’s a starting place. To be anything off center of that, you’re already excessive. You, personally, are excessive and your work is too. That’s something that in hearing you talk and hearing names of artists I’m thinking. What is the relationship of the artist’s body and their work? That’s always a major element. Not just the way that they look, but how we imagine them to be. How we place that in the seeing of the work or in the doing of the work. My body will never be separate from my work, even if I am not performing. My relationship to queerness will never be outside of my work. Even if these things aren’t named by someone seeing the work, they often perceive offness. They are being tugged away from center.

AE: A thing that’s compelling about your work, something commentators seem blown away by, is your presence.

JR: It’s because I don’t look like everyone else. But it’s also because I’m a good dancer, because I’ve been training as one just like millions of other people have. Reading reviews that comment surprisingly on my dancing ability gets me fiery. I have to weed through the virtuosity of wanting to prove myself in those moments, not over performing, being inside of the actual work that was crafted and not drifting into territories of delivery that can often over shadow the subtlety of what the work is doing.

AE: Yes. I was really struck by that because what else would you expect? She’s a beautiful dancer.

JR: I’ve practiced dancing for many years. I’ve worked with this one performer, Addys Gonzalez, consistently and he couldn’t be more different from me physically, so we kind of act as backdrops for each other. We’ve actually, through the work, had to really fight against that external viewing of form. Very early on it was said “you are the luscious, extreme, maybe excessive performer who whips your hair around.” I don’t really whip my hair around but I have long hair so it does move when I dance. And he’s this Greek God of a body. Writers, and even audience and friends, position us in this oppositional manner. The rebellion coming from Addys is astounding and something I want to witness and something that will keep me curious about his body. He often says ‘this is not a Greek body, this is a Dominican body and it’s strong but it does break and it wants to have long hair too sometimes and flip it around.” There’s a really quick read that happens. I don’t think it is just dance that does this framing. Women who are not thin are immediately read. Women who are thin are read as well. I find interesting the extreme levels that I can never quite understand, or hold onto, of complete invisibility and complete visibility. The relationship between those two for me is a bit excessive but it’s there. It’s always a wavering participant in the work.

That’s why I talk about getting the sentimentality out through writing. Sometimes I have to negotiate my body beforehand because I don’t want the content to necessarily be about the bodiness of the way I look. Even though I won’t hide that away and I’ll often be very proud of it, but the aboutness of the work might be something else. How do I get to that? How do I then use my body, or embody that as work? The feminine, or feminism or femininity, are major questions and also confusions inside my work. My deep relationship with this male collaborator who is often negotiating his relationship to femininity inside of the work leads me to look for more ways to support his male body. I’m often negotiating my relationship to masculinity. We’re both deeply interested in problems and what we don’t quite know yet is. Do we have permission to showcase problems, especially when they most often come out in a problematic way? During one talk in Toronto—I toured with Young Jean Lee’s Untitled Feminist Show (which is a whole other conversation)—a man in the audience said “What is it about feminism? Why do you all identify as feminists?” My heart started pounding in a real important way. This is not about just the cisgendered female body needing to reclaim their power, although it is also so much about that. This is not about me needing an identity to hold onto, although it feels so important that I can identify with this. This is a really large landscape and set of issues that include this man who wants to know why I identify as something, as if it is outside of something he could identify with or feels as though he needs to. The question directly placed on aggression onto my body.

AE: Constant.

JR: I was looking through the program from the NYU conversations (I’m jumping now to something else) I saw this Paul Taylor history by Fred Herko. He says, “Love is ultimately beautiful, love is interesting, love is exciting. It was lovely to watch Paul Taylor. Paul Taylor is not lovely to watch. Paul Taylor is not exciting. Paul Taylor is not interesting.” He goes back and forth between this positive and negative or this is or is not. I feel like that is so present or maybe truly part of the queerness and truly at the center of a femininity, a feminine source that isn’t only negotiated on the female body but in a way is a lot like queerness. It’s a thing we don’t quite know yet and it’s an ‘is’ and an ‘is not’ and I’m often ‘not not.’ I’m often inside of the space of people saying, “is it or is it not?” Especially in writing, when people edit my writing—well is that this or is that not this? I understand where that clarity can be useful and I also relate when I read and see and feel things that aren’t clear, the excessive nature that comes with that. There’s something in that that I understand.

AE: Same here.

JR: That feels deeply feminine to me but can easily be swayed as “you don’t know what you want.” Or, “you have a lack of clarity around the form.”

AE: Fluidity is an issue. It always stakes a claim.

JR: That whole talk—I became hyper focused on Mark Siegel’s notion of gossip. For me it was the ultimate. It was everything for me in that moment of welcome to the body! This is how information passes over time. This is how lives of people pass, how dances get made. It’s such a viable form of archive and documentation and I just felt like it was being written off!. It’s almost like he’s not historicizing Herko by talking about gossip. I feel like I got the best account, the most reflection on this conversation, through his singular presentation and proposal of gossip.

AE: It’s a beautiful juxtaposition too. On the one hand, a demand for historical fact versus “this is gossip.” The thing for me that was really profound was the way in which formulating Herko’s life and work through gossip becomes a way in which things actually circulate in the world, right? It always circles back to the fact that it’s sort of like history is with a small “h.” The capital “H” is just ridiculous. [laughter]. The papers can only tell you so much. You only get the things that were deemed worth saving. What happened with what went in the garbage or was burned? The night of anger with the lover, maybe some things went up in flames.

JR: Or even what actually did happen, even if these are your first hand accounts. Someone pointed that out.

AE: It is all perception.

JR: But someone said it in the combat mode of “You trust Carolee’s account of her own work?”

AE: Yes, which I thought was brilliant.

JR: Yes, it’s brilliant. Of course, my account of my own work is going to be as skewed and as gossip-riddled as anything. In starting this conversation, thinking about the people who I named, Greg and Walter, I think about how they would be renamed and retold and it would be gossip-riddled. How I am retelling them now is trails of stories of, “I saw or I met him here and this happened,” oh yeah, and “the work included some ballet moves.”

AE: Gossip is super productive.

JR: It really held a space for me of the flamboyancy of what everyone wanted to say. Everyone wanted to say this artist is profound because he was operating in a liminal space and queerness was all over him and his work and it was not supported. I think that’s the whole thing with queerness and being in that minority space; it’s not being supported and it’s still operating. How crazy is that? It’s probably operating with aggression and distaste and discomfort. But it’s operating. I think there’s a push and pull between wanting to celebrate this person, but also an element of how can we celebrate something we don’t know? That’s the center of dance for me. It’s the center of performance. We keep coming together thinking this is going to be it, but what is going to be it? So we have to start thinking about what’s important. Some people think his reference to ballet was really important, some people think that doing a lot of drugs was really important, some people think his suicide was important. Ultimately, I think the glorification of one human being onto the whole form or scenario of potentially queer dance in a non-queer dance community is a little large. I think he was operating at certain levels and other people are operating at different levels and there is somehow still presence there. That, to me, is the most interesting thing. He was still in the room. Maybe he was too excessive but he was there still, and that seems historical.

AE: I completely agree.

JR: It’s so interesting how heated everyone got.

AE: I think that has to do with Herko. I’m thinking particularly about this chapter that José wrote, even Herko’s closest of friends were at this point railing against his unreliability. “You’re off-course,” di Prima said. That can singularly describe the work that he did in life and in the afterlife. This kind of off-course, this being off-course. Di Prima’s complaint in some ways perfectly describes the way in which he occupied space and now, gossip or memory or mythology, is off-course. “That’s not the way I remember,“ the witness said—It’s so interesting.