This article has been edited for the purpose of publication.

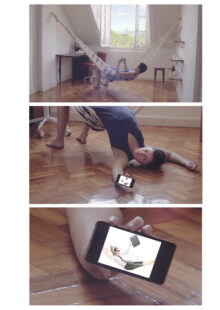

Dancing for the camera has been a practice long taken up by experimental dancers. It was synonymous with new ways of thinking about choreography and space; it also resembled a challenge taken a step further. A way of swapping the square of the stage with the square of an articulating screen. Sofia Caesar and I both have practices that involve the use of a camera. We incorporate the images it captures making it one of our witnesses. Our practices live in the porous state of being between mediums, of taking failure as a door to new possibilities. In this conversation we share thoughts and feelings that we have encountered while taking a chance beyond traditional structures or how we have come to call it, “embarking on the dance of the lonely“.

—Nicole Soto Rodríguez, CC Co-editor

Sofia Caesar:

I always say that I’m very lucky that I failed at my dream to be a dancer. I think that was a very lucky move.

Nicole Soto Rodríguez:

Wow, That’s awesome! I wish I could have seen it that way.

SC:

By failing I ended up here, failure got me where I am.

NSR:

Failing is not a concept that we talk about in the dance world. The dynamic of the dance world is capitalist and competitive, there is no space for failing. You are always trying to stand out by being better technically or conceptually and to be honest, it’s exhausting. I don’t know if you can relate? but sometimes I didn’t even enjoy my training because I was so focused on succeeding. If I wasn’t getting to where I thought I needed to be, everything was doomed.

SC:

Well, I feel very lucky to have studied in a school that focused on therapy through movement, the school was Angel Vianna. I was fortunate to study in a place that was more focused on inventing a body of work, for yourself. Then I ended up with a tool at hand, which was the camera, filming and editing. That’s why I mentioned the idea of the lonely when I was listening to you speak. I didn’t mean lonely in the sense that you’re alone, or you’re melancholic, but more that there is something about singularity, something that is singular to each body. I like that the camera somehow allowed me to go through that path.

I don’t know about you, but at first I didn’t know where I was going: if I was dancing or if I was making video art, or if I was making an installation. But it was a way to survive, and to do what I wanted, outside the dance company world. Doing that without having to become an interpreter, or like part of a mass, of the block that can be the dance company. That structure was really difficult for me. This thing of having one authoritarian figure who passes on their own subjective experience of the world, and it passes it on to other bodies as movement. It can be beautiful, letting go and becoming another body and sharing and creating something together.

But at that time I was so young and experienced so much pain that I needed to single myself out to be able to heal on my own and to deal with my body. I also wanted to know why my body was so chronically bizarre. And that’s what I mean by loneliness. The dance of the lonely as one person dancing on their own. Dancing with a camera can give so much to an individual in the sense of self knowledge and self awareness. I don’t mean it in the sense that you see yourself in the eyes of the camera, like a mirror or self reflection, but self awareness in the sense of exploration of creation. To me it was a way to make work in a country that didn’t have the means to give young dancers financial support to develop their own work.

So how can I deal with this? How can I create something? What are the tools I have? I have no money but I do have a camera. For example, I had an exhibition coming up. I met some people that had found an abandoned house and they were making a group show and invited me to dance. I ended up making a video installation. There was a solitude there while I was dancing for the camera that I enjoyed.

NSR:

I was going to mention the word solitude. I think that working with the camera allowed me to be more intimate, or more vulnerable than what I would allow myself to be in the theater. Because, even if you are doing experimental choreography or focused on the concept, the structure of the theater is always there. You are not necessarily that honest because you are always portraying something to the audience on stage. So even if all the works that I showed on stage were honest, I didn’t really feel like it was connecting enough with the audience.

This led me to consider performance more, because people are part of the work, they are closer in terms of their bodies. But with video, it allows you to show more intimate experiences. I have recently learned that I am an introvert and sometimes I am overwhelmed when I am with a lot of people at the same time. I really don’t like being the center of attention. Somehow the solitude that I explore with the camera allows me to feel safer while being seen. Because the audience is there, but they are not really there. They are observing me in an intimate act but I do not feel as exposed as I would feel if they were with me in the same space.

SC:

It’s the difference between witnessing and being looked at.

NSR:

That’s what it is, there is some sort of relief of pressure. One of the things that I have been working on is allowing myself to show more honesty in the process of my videos. So I try not to edit that many things, or I will show different little errors so people can see a less polished process and finished piece. Maybe that is why I’m working with camcorders or analog video because I’m trying to figure out how to show the mundane and the errors. The first step to be more honest was to keep working with the camera that I started with. The camera that was in my household in the late nineties. That is why I am working more and more with a Hi-8 camera. I’m just interested in that intimate moment of showing someone something and how that can be seen as it naturally is with less editing from my part. The less noise that it has, the better for me. But I’m still allowing myself to find a way in this process. I don’t know if you have a similar experience?

Sometimes I feel like I’m in this ambiguous state, shifting between video and movement. And I’m still obsessed with movement, but somehow I’ve been moving towards other types of movement that are not related to the human body. I just had an exhibition that was about different ways in which there is movement in lights. And it was videos of lights not working and moving all around in public spaces. My first home is movement, but sometimes I feel like I put too much pressure on it. I go through a lot of negotiations in order to work with choreography, or to move in a space and then sometimes it gets too intense.

My first series was in abandoned spaces. It was out of necessity because I felt abandoned by a country that would not give me what I worked so hard for. I felt that maybe I needed to face reality and abandon the dream of being a dancer. That is why I decided that I would submerge into that feeling and work with what could come out of that premise in a space that was no longer in use. I shared the abandonment that I felt, which was physical, emotional, and social. It was intense at the beginning but I think that because it was honest, and I was really going through something, people connected with it. It allowed me to keep working with movement. Now I’m in a place where I don’t know how to insert the body again into the video. But I guess it’s just a process, and I will figure it out eventually.

SC:

Yes, for me the body of the people that are looking at your body also becomes important.

NSR:

To me it becomes more important in exhibition spaces. I think about this a lot, how do other people negotiate with ways in which they would need to position their bodies in order to watch a video?

SC:

The thing I love about video exhibitions is that rooms that are showing the video get (I don’t know if this word exists in English) usurped for other purposes. For example, you could see the invigilators of the museum go and sleep in the exhibition rooms when there are not a lot of visitors. It is the kind of space that gives you relaxation and kind of feels like a shelter. All these things turn into experiences that are possible in exhibition spaces or museums and are taking a detour from the productive chain of the museum.

People go to museums and they say “hey we are going to the Museum, we want to see the Mona Lisa at the Louvre” and then nobody is really looking at the painting, they are looking at the screens of their phones. I find those moments very interesting. The body goes to other places, not the choreography that the museum had drawn out. I find it important to think of lights, air conditioning, seating, etc. These structural aspects are important in how the body occupies the space. In your case it’s beautiful how light affects us and how it affects our bodies. And it’s a dance. For me, it’s all dance. Even if I show a painting, it’s all in the realm of dancing to me.

NSR:

I definitely see it as dance or dancing. It is a choreographic exercise. I ended up having different screens in different areas and I had to choose how they would turn on and off. Where they would be located in order for people to decide how to move around to be able to see it. But that’s the thing I’m always thinking about spatial dynamics and movement, and how you will negotiate your body in relation to that. So there is a dance, there is always some choreography in there. Even if I’m just thinking of an installation, the body is never out of it. I think that I can’t have it any other way. That’s just part of what I see or what I experiment as a person, as an artist, and as a body.

SC:

To me dance is a ritualistic thing. A social thing. A social dynamic, like looking at a group of people moving in the street. There is choreography there, there are bodies coming together and moving together and inhabiting places together. That’s nice about exhibitions. Many dances are possible. Thinking about spaces or trying to play with dancing in them is important.

NSR:

How space becomes more than just a place where we are at. Which is something that I can really trace back to being trained as a dancer. Space is never just there, It’s always there as a presence.

SC:

It’s never empty.

NSR:

No, it’s never empty, there is always something going on in the space, there are bodies passing through, even if it’s a lizard’s body. I really appreciate that I learned this while being a dancer. There is this awareness of space, of different levels of space, the corners, the materials, the forms. It gives you something that allows you to step outside of the dance form, and work with other mediums that go beyond just space and body. I really like that.

SC:

Uhm, yes!

NSR:

But maybe it is a generational thing as well, having all these experiences and then working with these themes. Like collapse and failure and the things that we aimed for but didn’t get to experience or didn’t happen for us. All of it relates to the human experience. And I feel that we are not even trying to portray a particular human experience, it’s just that these are the things that we are going through and we need for them to leave the body in some way.

It is overwhelming, at least for me, and sometimes I have to approach movement as therapy. I think I see it as a ritual, like this is the way that I can actually survive as a body that inhabits space in this existence. Maybe that is my process with these rituals, they become a way in which I figure out how to release those feelings and ideas from my body.

And it replicates with other colleagues, people working with spaces, with houses, with parental relationships, with memories and fictions created around the family and the self. And they live with us in the spaces that we go in and out of. And I guess maybe, we all go back to the same things even as we are different generations. But failing, I’m interested in failing or in portraying something that has to do with what I experienced socially as failure. Feeling stuck, or that everything’s collapsed, or that you try once or twice and it still doesn’t work, and then you have to keep figuring out something else.

SC:

Improvisational movement.

NSR:

Yes! There is a constant action of having to improvise. I remember a moment when I was obsessed with improvising, thinking of having new movements or new vocabulary of movements in my body. Preoccupied with the idea of how to refresh my movement vocabulary or to put myself into a position that would push me to create new movements. As if that’s something that can happen!

SC:

I love that. When I first experienced dance improvisation, I was sometimes invaded by one thought. If you think about it, humans can be so limited. If you’re really lucky you have one head, two arms, two legs and a middle. There’s not much we can do with this combination formally, like in terms of permutations. So what can we do to experience something else? What are the movements that say something else about the body? It is such a mysterious thing, the body, and we can explore the mystery in improvisation. To me improvisation is about letting go of the desire for success. It’s about seeing what comes from the failed attempts. That’s how other languages are developed. That’s at least the way that I see it.

NSR:

Uhm, I have this particular relationship with improvisation where I fell in love with it when I started practicing it as a teenager, and then I kind of got stuck, because I didn’t know what new things to do. Usually it was a struggle because I was worried about being too aesthetic, or I was frustrated because I always ended up doing some technical stuff, some pirouettes or I was too stuck on lines or kept moving in the same space level. I was desperately trying to get out of that dynamic, but in that process I was trying to control it so it did not work and I wasn’t allowing the body to explore whatever it could or it wanted to in space.

I still struggle with it but I did make peace with the process. It happened when I did a series that was called restrictions where I allowed my body to move as it wanted to even if there was a lot of repetition or if I kept dancing at the same floor level. I think it worked because I felt this relief when I allowed myself to be small if I needed to. And that was one of my issues as a student of ballet and contemporary. There was this expectation that I would take more space or be able to move furthest in a diagonal or jump higher because I was taller than other girls and it didn’t happen. I kept moving in small spaces and that was a problem for my teachers. My body wanted to be small and just do slow floor movements. So I ended up fighting it until I decided that maybe that is the way that my body feels like moving in its truest form.

It has also a lot to do with the history of how my body was formed inside of my mother’s womb. Doing research on the history of my body allowed me to understand this better and to be able to go beyond the idea I had about my body. It also allowed me to understand the reasons why if I’m so tall I can’t take that much space. So these are negotiations that I have gone through and that I have learned to accept in order to allow myself to do something new or to just move again. I still don’t have an answer for a lot of questions and worries that I have, in terms of movement, but I’m here being more true to my body’s ways.

SC:

I think the body is our ultimate boundary no? a contour. We need to see that bodies are always relational. They exist because something else is there. If there’s no limits to the body, there is no body.

NSR:

Ahh yes! Boundaries! That’s a whole other conversation.

SC:

Yes, gravity being the first one.