susan karabush: I’m wondering if you could start off by talking a little bit about your history with Silent Barn and Silent Barn’s journey to legality.

Mike Lawrence: Ok, so I’ll start off before I got involved which was 2006. Silent Barn has been around since that period of time. The last space we were at was more like a warehouse where people lived and obviously that’s not legal. You can’t just throw shows in a warehouse where people live for various reasons. So Silent Barn existed for four or five years in that incarnation and then the city caught up with us. They basically came in and condemned the building, shut us down. And in the process of us being closed down our gear was stolen in that location. The people who lived there were determined to bring Silent Barn back so they decided to start a Kickstarter campaign. And the Kickstarter campaign was successful obviously, we raised $40,000. Through the Kickstarter we also got a lot of outside financing from individuals. We have a relationship with a community bank in the neighborhood. So with those resources we were able to find our current place and sign a lease for that building. That lease was signed late 2012. I came on board around 2013. I’m a lawyer, but I have a relationship with the old Silent Barn in that I went to shows there. I found out about the Kickstarter, backed the Kickstarter, and reached out to people at Silent Barn to see how I could help. It was at a time where they were consulting with a lawyer pro bono, but that lawyer couldn’t continue doing that because his firm didn’t approve– not that they didn’t approve of us, but just the time he was putting in on a pro bono basis. So I came in at that time not knowing the backstory. I just came in and decided that I wanted to help, reached out to a few people, and I just became Silent Barn’s lawyer. In that time I’ve done a lot of various things. I actually negotiated an amendment to our lease a few years ago, that’s one thing that I’ve done. Any time we interface with the city, we’ve had audits from the NY Department of Labor, I sort of interfaced with the city on those matters. I helped draft subleases for tenants. We incubate businesses and we also house tenants on the second and third floors. So any contract that the space needs in that regard I help draft. Now we’re in the process of becoming a non-profit, a 501(c)3, and I’m helping the space become a non-profit with the state and federal government. We’re working with a bigger law firm as well on that. So a lot of things are happening. I also moderate public meetings. The last one was on funding DIY enterprises which was really successful. I also lead a public meeting on how to legalize a DIY venue. And I also consult with other DIY spaces in the city from time to time. That’s, in a nutshell, my involvement.

SK: And I think you mentioned the other day that since you moved to the new location you haven’t had issues with Cabaret Law enforcement at Silent Barn.

ML: The Cabaret Law I think is a hot topic nowadays, but I don’t think very many places have issues specifically with the Cabaret Law. I think what happens is that when a place becomes on the radar of the authorities by whatever means, like if there’s a lot of noise complaints, if that place just becomes known as a nuisance, or a general nuisance to the community, that’s where the M.A.R.C.H. program comes in. M.A.R.C.H. is the Multi Agency Response to Community Hotspots. Once a place gets on the radar of the authorities by various ways they become recognized as a nuisance and typically M.A.R.C.H. comes in and they raid the place, essentially. They find a whole host of violations, y’know, some of them legitimate. And I mean I’m not going to name places, but there’s been several venues that have been M.A.R.C.H.’ed in the last five to ten years. So yes, the M.A.R.C.H. program comes in, they raid a space, they find all these violations, and typically, the Cabaret Law is like an add-on to that.

SK: Right, it might be a Liquor Law violation or something like that?

ML: Yeah. So, I mean you can correct me if I’m wrong, but I haven’t heard of a space getting shut down exclusively because of the Cabaret Law. But the Cabaret Law is a useful tool for law enforcement in that it’s something that can be arbitrarily enforced. It’s something that can be thrown in with a host of other violations. The Cabaret Law itself, it’s pretty vague. I’ve looked at the language of it and basically what it says is that if you have more than three people dancing then you need a Cabaret License. No one really knows what is meant by the term dancing. I mean no one knows if it’s bobbing your head, if it’s like moving your hips in place, is it moving your feet? Y’know nobody really knows what it is…

SK: If you’re not having fun, does it…?

ML: Yeah. If you go back to the history of the law I think it’s a hot topic now not because it’s particularly used as a means of enforcement, but the intent behind the law is very discriminatory and racist. When it was enacted in the Twenties the intent behind it was to prevent white people from going up to black neighborhoods in Harlem and to use that law as a way to shut down these jazz clubs in Harlem. I think now that people are becoming aware of the history of the law it’s become like a moral outrage which, right now, it should be. So the law definitely in my opinion needs to be repealed, but I think we need to go broader in terms of some things that might help DIY spaces both start and stay around longer. And you know, there’s proposals, there are proposals on those fronts being bandied about. But yeah, I think the law itself is very vague, it’s arbitrarily enforced as we saw during the Giuliani tenure, just out of nowhere a lot of places were just targeted and shut down because somebody came into office who just didn’t like the idea of DIY.

SK: And when the M.A.R.C.H. hammer is slammed down, whether it’s the Department of Health, Department of Labor, they say “we’re not out to get you, it’s a safety concern. We’re concerned about the safety of your patrons.” Do you think that’s valid? What do you think the most pressing safety concerns are for DIY spaces?

ML: I think it is a legitimate concern in some cases, but the way that it’s handled I think is not the right way. I think if safety is the issue the city can work with places. It’s not like people don’t want to be safe you know what I mean? I’ve talked to a lot of people in DIY and just nightlife in general and no one’s more concerned than the people who are running these venues and starting these businesses. But it just seems that in some cases by the time that it gets to the M.A.R.C.H. level, it’s more like a Gotcha Game, y’know? If safety is an issue, and I think it is a legitimate issue, then there should be some part of city government that’s working with places to improve that safety rather than just coming in and being like “Oop, I got you! There’s that egress violation. You didn’t have a permit to construct this structure. Let’s just shut the whole place down.” I mean, I think the city can do a lot more to work with venues as opposed to finding reasons to shut places down, shut down the culture. As far as what are the most dangerous violations…

SK: Or not even just violations of the law or building codes. What are DIY venues actually concerned about in terms of safety?

ML: I mean obviously Ghost Ship happened a year ago. Nobody wants to see fires. So anything that can be done to lessen the possibility of a fire I think is a good thing to do. And there are certain things that should be done. There are codes like, you want a clear egress. You don’t want items blocking areas where people have to vacate. You want to have fire hydrants. You don’t want to use power that’s mostly by electric extension cords. Even the way that you might have to use extension cords for some things, but the way those are set up are important. You don’t want to have combustible material on your site. You want to have the proper number of exits and you want to don’t overstress your property by having too many people there. There are certain guideposts that people should be abiding by. And I think the city could do a better job of working with venues and promoting culture rather than trying to stifle them, in general.

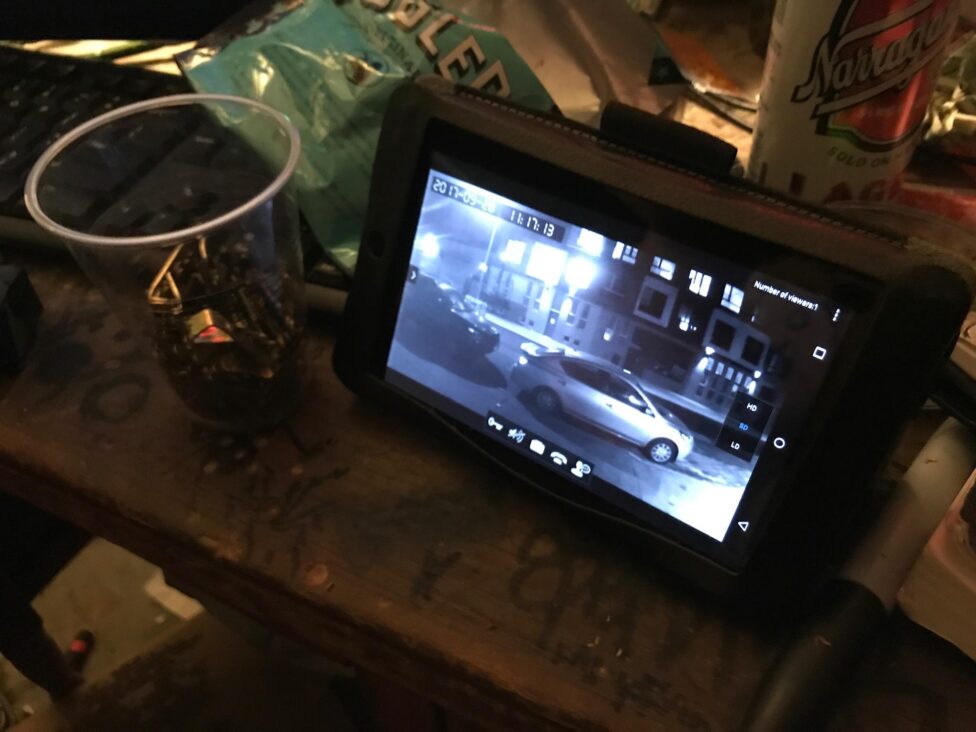

Photo: Security System at another space in Bushwick. Photo by: susan karabush

SK: You mentioned you’d like to see the city do more to help DIY spaces stick around and work towards being safe. What do you think would be helpful coming from the city in that vein?

ML: There’s been a couple of proposals. It’s expensive to comply in a lot of cases. If there could be a program where the city has certain contractors or a fund for critical repairs I think that’s something that’s realistic and can be done. Another thing, just overall, promoting the startup of businesses. Even if somebody starts a DIY space illegally I’d rather that, rather than shutting them down, maybe there’s a way to encourage those places to start legally and maybe point those people in the direction of resources. Maybe point them in the direction of a community bank. Or point them in the direction of lawyers who could help them negotiate a lease. So I think those basic things. I think the process with the Department of Buildings should be streamlined a little bit. I talk to owners of venues that are not even in DIY but are bigger and they regularly go to the Department of Buildings just for the smallest things. It’s not easy. Once you get into that bureaucratic maze there might be a legitimate problem but then it’s just not efficient to go through the whole process of finding out who you talk to at the Department of Buildings. The person at the DOB might tell you something that conflicts with another agency, so you could be running around in circles for months trying to fix a simple problem. So to answer your question I think some kind of a fund with the DOB where you have contractors, things of that nature, to help spaces with those burdens, structural burdens, just maintaining a physical space. I think on the front end: working with people who may have started illegally and try to get them the assistance whereby they can legitimately start a venue.

SK: So the publication that I’m talking with you on behalf of has an audience of mostly dance artists and choreographers and I work professionally in a concert-music space. Addressing the divide between the theater-dance/concert-music scene and social dance/dance music scene, can you speak to the importance of dance in your personal experience of the creation or enjoyment of music?

ML: I think it’s important. I think for me, I can only speak for myself, but a lot of the music I tend to be into, I’m definitely into dance music, you know hip hop, other forms of dance music. Even the music that’s not that has, for me, had an element that calls to move your body. It doesn’t have to be a full on breakdance or anything like that but I do like to move to the music. And it’s a shame that there’s a law in place that discourages that. We don’t even know what is being discouraged, it’s crazy. If you go to a concert tonight and look out into the crowd, if it’s somebody good, I mean I don’t care, it could be even hard rock, most of the people are moving their bodies in some form or fashion. So I think it’s important. There’s an important piece to it. People come here, to New York City because it’s supposed to be a cultural hot spot. And so if there was a campaign that told people around the world that you could come to New York but you can’t dance, I mean that would be pretty shocking to people. I’m pretty sure that people would think that’s a joke or would be like, “Then why is New York New York?” You know what I mean? So yeah, I think it is a crucial aspect of it. And I definitely have had that thought, even in just my personal enjoyment of music, that if I go to a concert, and it could be a concert of somebody I’m not familiar with, but if I’m not moving my body it’s definitely something I notice and is definitely something that I’m like “Wait a minute, I didn’t, I wasn’t, like, moving.” And sometimes I’ll look around and if people aren’t moving then it’s like… either it affects my opinion of the artist or, to me it’s just a natural way of being when you’re in the audience and you’re observing art and music or anything that it has an affect on how you use your body.

SK: Do you think there is a spiritual importance in terms of community building for social dancing?

ML: I think it’s something that people have a need for. You know what I mean? It’s not really talked about a lot, but all kinds, every community you can think of that’s a big part of the culture. People go to weddings they want to have a good time, they want to dance. Every social event is built on music and dancing. Your question is what is the social importance of dancing?

SK: Yeah.

ML: I think it’s a huge importance you know what I mean? I think yeah, even in our culture, I mean America, which is in a lot of ways more conservative than other places in the world, people want to do that. People when they go to a concert it might not be full on dancing but they want to move their bodies. When you go to weddings or parties they dance. When you go to other cultures around the world it’s the same thing and it’s even more ingrained in those societies. I took Salsa lessons a year or two years ago and if you go to a Salsa Club dancing is a little different. You could be dancing with somebody’s grandmother or your grandfather could be dancing with a teenager. You know it’s not anything like… it’s not a big deal, it’s just part of the culture, it’s how people express themselves. And I think even here, where dancing is discouraged, it’s a big part of the culture. So, I think that’s one of the most important reasons to get rid of the Cabaret Law. It’s a law that’s really just goes against the nature of people and how they express themselves and how they enjoy live events.

SK: Definitely agree with that. Do you have general advice or legal advice for DIY spaces facing M.A.R.C.H. or other discriminatory law enforcement?

ML: So you have to prepare beforehand. And there’s a lot of things that go into it. There’s a lot of little things that add up to M.A.R.C.H. showing up at your door. I think the first and most important thing, we have to recognize, a lot of people in DIY have to recognize that we’re a gentrifying force. So [even if] you’re a native New Yorker, you probably didn’t grow up in the neighborhood that you’re starting the venue. So I think the first thing you should do even before you actually start your venue, you have to do that anyways, you have to go to a Community Board Meeting to get a Liquor License, but I think don’t do it just to open your venue. I think you do it to have a legitimate relationship with the community. And I think that’s something that Silent Barn does well is that we’ve always made an effort to include the community. Not just go to meetings, but include programming that’s going to be appealing to the community, talk to your neighbors, do that sort of thing. There’s going to be a loud show, you want to tell the Community Board a few weeks before so maybe that’ll minimize the existence of noise complaints. And if you’re lessening the existence of noise complaints you’re not on the radar of the authorities. And if you’re not on the radar of the authorities then they’re not maybe poking around trying to find a violation when maybe there isn’t one, y’know? Or maybe it’s something minor that most venues probably already have. If the owner knew about it they’d just fix. So yeah there’s a community aspect to it and there’s also sort of an operational aspect to it where a lot of DIY places they just want to be about the art or be about the show which is cool, but you are running a business so you have to talk to and have to have a relationship with a bank. I think it’s helpful to talk to your banker about your goals and maybe they have advice to you as far as what you can do to make things more legitimate or go to a bigger level. You want to talk to a lawyer obviously. [There’s] things that you’re going to come across that you need the help of a professional if you’re going to negotiate a commercial lease you definitely want to talk to a lawyer about that. There’s little things like sales tax and paying employees. There’s just so many little things that if you’ve never run a business before you would not even think about, but that’s why you should reach out to professionals and learn what you don’t know, essentially, because there’s a lot of well meaning people out there that have positive goals, but if you don’t know what you need to do to survive then that’s going to not be good for you in the long run. So yeah, I’m trying to think of anything else. Yeah, I think those are the main things, just talk to different professionals, establish a relationship with your community, try to include them in the programming to the extent that you can and uh yeah, just do good things. Like if you have a space and you could use it for child programming, y’know? There are little things you could do. Spaces are lying vacant for the most part during the day that could be used in a way that helps people, includes the community. Just keeping a venue alive is not a matter of just hiring a lawyer. You have to have good relationships with the community, with the authorities. You have to have a story for when the police show up. Who are you? What are you doing? You have to demonstrate– and this isn’t just a legal thing. It’s a matter of competence. You have to demonstrate that you’re somebody who knows what they’re doing. You have to give the authorities confidence that you are somebody who can handle the responsibility that you have. And it’s not just, “Aw I did everything right and F the police…” Although, I can understand that sentiment. It’s like, okay, we have to deal with law enforcement, we want to be a positive force in the community, so how do we conduct ourselves, how do we express through different people that we are a competent business owner that can handle the responsibility that you have. So that’s my two cents.

SK: I might be out of questions, is there anything you’d like to add?

ML: I think we covered a lot. I mean one thing I do, and I think this goes back to maybe the divide between the theater dancing and audience. I looked into the Cabaret Law. The Cabaret Law has nothing to do obviously with the performers. You could be dancing on a stage if that’s part of your performance, or you could be in a band where a lot of your act or your, yeah a lot of your performance involves dance, but the Cabaret Law has to do with the audience, not the people performing. So yeah, I mean, this goes into what we were talking about before. I don’t think that’s the policy we want to have. We don’t want to discourage people from enjoying themselves, especially when it’s so arbitrary as to where we don’t even know what we’re discouraging so that’s just something to keep in mind. I think the more that we tell people, like I was saying before, if we had a campaign to abolish the Cabaret Law and we were telling people “Did you know that you can’t dance?” “Did you know that you could be shut down if three or more people were dancing?” I mean that just sounds ridiculous. And so yeah, I think the more that we actually ask ourselves why do we have this policy from a practical perspective and then also the racist origins of it, I think most reasonable people would say it’s not something we really want to encourage or have on the books, so yeah I think it’s important that we do whatever we can to repeal the Cabaret Law. That’s it.

Photo: Punx of Color Photo Series at Silent Barn. Photo by: Destiny Mata

susan karabush: Can you tell me a little bit about your history with and efforts to repeal the Cabaret Law?

Andrew Muchmore: I graduated from law school in 2008 and moved to New York and while in law school a lot of my focus was on constitutional litigation and the procedures for challenging the constitutionality of laws. Then when I moved to New York and began looking to open a venue one of the things I came across was the Cabaret Law and had to make a decision about whether or not to pursue a cabaret license and to modify my conduct as a result of not having a license. There were so many that were required for other activities to submit the licenses that maybe I should not do, that virtually all other people in New York did not apply and there were only about 100 places that had licenses at the time. I didn’t think too much about it until one year later in 2013 when I received a ticket for unlawful dancing during a concert. So then I thought that might be a good opportunity for me to use my own bar as sort of a test case and test plaintiff to challenge the law.

SK: The law was repealed this past November, congratulations! After years of effort from many groups to have the Cabaret Law repealed, what do you think finally contributed to this year’s success?

AM: I don’t think it had been challenged in the right way before. I think that there’ve been three or four challenges. One only dealt with character requirements for proprietors, one dealt with only limited aspects that were determined to be unconstitutional. There was the case Chiasson v The City of New York where they found that the aspects prohibiting the use of instruments commonly used in jazz. Playing wind, brass, percussion instruments without a license was unconstitutional and the prohibition limiting the number of musicians to three was unconstitutional and [the Chiasson case] was limited to those aspects of the law. And then there was a case with the New York State constitution, Festa v New York in 2007 which was unsuccessful but that was in large part because it was brought on behalf of social dancers and social dancers’ rights unfortunately are not strongly protected under the First Amendment. Dance performance is clearly protected under the First Amendment. The Cabaret Law did not distinguish between dance performance and social dancing and the city’s attorney took the position that they only applied the law to social dancing. However, many of the licensees were adult establishments that had dance performance but not social dancing and there was the City’s attorney took the position that it did not apply to dance performance. So when we brought a lawsuit there was a motion sequencer on the case, the City’s motion was denied and the court issued this forty-four page decision essentially agreeing with our legal positions but requiring us complete discovery. This put a great deal of pressure on the city to finally act. There was also a lot of publicity around that and lot of new supportive media attention that got the ball rolling and that got other groups involved. And then you had all these groups pop up like Dance Liberation Network and NYC Artists Coalition and we began more concerted lobbying effort towards various city councilmen to gather the critical number of votes we’d need to get the repeal law passed. So I think the time’s changed. It’s 2017 but even when the last push came to repeal this law in 2007 after the failure of the Festa case, social mores were not that different at that time. I think the pressure of the lawsuits combined with just a large enough group of people all pushing in unison, and a more liberal administration, all contributed to making it possible at this time.

SK: You said that the law would allow dancing as performance but not as social dancing. Are there laws or regulations on the books that tell you how to distinguish between the two?

AM: Well the law itself drew no distinction. It just said dancing. It didn’t define dancing. So it wasn’t even clear whether swaying or toe-tapping or head nodding would cross the line or when something became dancing. However there’s a long line of court cases protecting dance performance even within adult establishments and finding that was protected speech under the First Amendment, that it was primarily expression. There was a 1989 Supreme Court case called Dallas v Stanglin that refused to extend constitutional protections to social dancing. That case involved a roller-rink/discotheque in Dallas and there was an ordinance regulating teen dancehalls and the provider of that establishment tried to challenge the requirement that he separate the adults from teens and the adults couldn’t dance with teens and it was an unusual set of facts. The court held that dancing in a purely social context while it contains some elements of expression was not primarily intended as expression, it was primarily an activity and they didn’t want the First Amendment to be applicable to all conduct, it had to be primarily expressive conduct and they held that dancing was not primarily expressive conduct. That case has been somewhat called into question. It was distinguished by the Supreme Court in another case, but not overruled. There were a couple of cases similar to my case that had struck down similar ordinances in other cities. There was one in Florida in Hillsborough County where anti-rave ordinance was struck down. Then there was one in the Town of Pound, some tiny town in… I forgot what state that case was even from, but a similar ordinance was struck down there. There was no case law clearly holding that social dancing is protected by the First Amendment. Each of those cases relied primarily on poor drafting of the statues and overbreadth and that was part of the basis for invalidation as well. The Cabaret Law is also vague and overbroad and swept in far too much conduct. I tried to address how it impacted the rights of musicians because if you’re a musician and people can’t dance, you can’t play genres of music that will induce them to dance. And the rights of musicians are strongly protected under the First Amendment, so I thought that even if the court would not recognize the rights of social dancers, it would at least recognize the rights of musical performers and dance performers and all nature of performers. My place is a performance venue so I thought it was well-suited to challenge that, but the decision actually went much further than that and had a number of pages of analysis about the expressive nature of dance and how dance is fundamental to culture and brought up examples like the Quinceañera of the 15th birthday of a Latina girl or weddings or various other cultural traditions where dancing is very central and fundamental and questioned whether it is or should be protected by the First Amendment. Which surprised me because it went well beyond what I had expected. I thought I could successfully challenge the law on other grounds and that there was better support in the case law that I did not expect to get much traction in respect to social dancing being protected under the First Amendment.

SK: You mentioned that the rights of musicians are strongly protected. Can you say a little more about that? How did that come about?

AM: Just constitutional jurisprudence. Music has been repeatedly recognized to be encompassed within the First Amendment because it is primarily expression. There’re a number of constitutional precedents holding that it’s essentially an undisputed point of law so it made for an easier avenue of attack.

SK: So it hasn’t come up as often in court cases that prohibiting social dance is an issue of freedom of speech?

AM: There weren’t a huge number of court cases dealing with social dancing, but what cases there were followed Dallas v Stanglin. And Dallas v Stanglin, the 1989 Supreme Court case, its holding was actually a little more narrow than that. It didn’t strictly determine that social dancing was not protected by the First Amendment. The case involved a teen dance hall and relied upon the greater rights of the state to regulate the conduct of minors. So its holding was limited to minors but there were some dicta in the case that were extraneous to the holding, but it sort of hinted its reinforced opinion that social dancing would not be protected. And that was read more broadly by the lower courts and when the cases where this did come before lower federal courts, I think there were eighty-something cases citing Dallas v Stanglin, nearly all of them followed it with only a couple of exceptions like that Hillsboro case, and the Town of Pound case.

SK: A common defense of the Cabaret Law, and more broadly the M.A.R.C.H. initiative, was and is concern for public safety. As a venue owner yourself, what do you think are the most pressing safety concerns for spaces that host performance and dance?

AM: The Cabaret Law never genuinely regulated safety. That was misinformation that people who had never actually read the text of the law thought that it somehow promoted safety when in actuality nothing in the Cabaret Law had anything to do with safety. It was effectively just a prohibition on dancing. There are many other code sections from the books that do promote public safety. We’ve got the fire code, we’ve got the building code, you need a Place of Assembly Certificate of Operation if you want to host more than seventy-four people at a time, there’s a noise code. New York City is a very, very heavily regulated place and its politicians have the opinion that every problem can be fixed with a law and if it’s not immediately fixed just pass ten more laws. It’s that attitude that the Cabaret Law came out of. But I think the actual danger to venue goers stems from over-regulation. When you make it so difficult to comply with the law, people just stop trying. When the total cost of compliance would be somewhere around $100,000 to hire consultants and architects and lawyers and all other kinds of professionals, if you have a group of young artists who want to create an art space, they’re not going to have that money. So they’re just going to open up in some warehouse somewhere and there won’t even be rudiments of those safety protections. Some of those spaces are safer than others and they’re very culturally vibrant spaces, and I like those spaces and I’m willing to take my chances to go to them. But for cities that want to do more in general to promote safety, they would have safety laws that were narrow enough and simple enough that people have a realistic chance of complying with them.

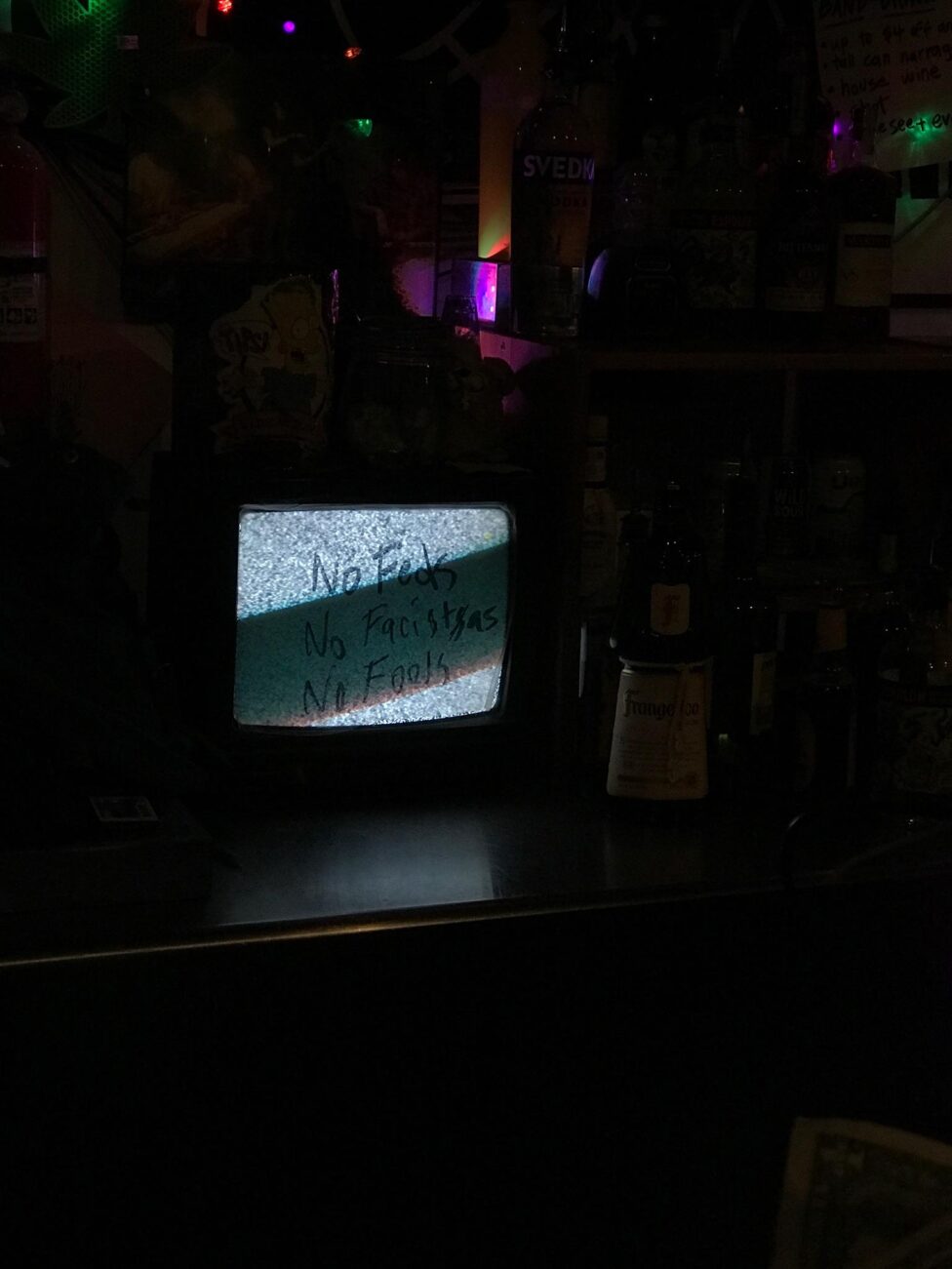

Photo: Silent Barn in the months leading up to the Cabaret Law repeal. Photo by: susan karabush

SK: In the NYC Artists Coalition’s letter to the mayor and the DCA they give some action points of what they hope to see achieved by the newly instated Office of Nightlife. Most of these points address the Department of Buildings, leases with landlords, city agencies and the process of getting a space up to code. When we were talking about the Cabaret Law, we were talking about law enforcement’s arbitrary and discriminatory practice of enforcing this historically racist law. So how did we get from law enforcement to the Department of Buildings, what’s the connection between those two issues?

AM: There’s still references to dancing in cabarets and the zoning resolution in the building code and those need to be eliminated as well. I think they will be eliminated in the course of the upcoming year. For instance the building code requires fire sprinklers if you have dancing, it does not require fire sprinklers if you don’t, just as a general rule depending if there are other factors which could trigger the requirement for fire sprinklers, but that can be a very substantial cost, many tens of thousands of dollars including replacing a water main if you don’t have sufficient water pressure to support them. So that’s an example of how having dancing could trigger very substantial costs and I’m not saying that no space should ever require sprinklers, I just think they should just be based on capacity rather than whether or not you have dancing because dancing doesn’t do anything to increase the risk of fire. And the same for the zoning resolution. The zoning resolution effectively prohibits dancing in certain zoning districts, you have to be in a high density zoning district that permits Use Group Twelve to either have a capacity of more than two-hundred people or to have any capacity with dancing. And then Use Group Six which is for most bars and restaurants allows a capacity up to two-hundred people provided that there is no dancing and those brief references to dancing in the zoning resolution also need to be repealed but that’s a lengthier process. It has to go a few different stages including the Department of City Planning, it’s just more complicated to amend the New York City Zoning Resolution than to amend other provisions of the Administrative Code.

SK: So now that the law has been repealed and that they have instituted this new Office of Nightlife what’s next? What do you hope will come out of the law repeal and the new agency?

AM: I’m hoping that we’ll start to see at least a decrease in the rate of decline of the live music business. The economics of this business are very difficult and this was one thorn in its side. I know in Williamsburg a number of places closed down over a relatively short period of time and I would hope to see that trend arrested.

SK: I like how you’ve framed the issue as a concern for musicians. Not only because of the intimate relationship between music and dance, but also because of the rate of decline in the music business.

AM: Yeah the two go hand in glove. Music and dancing are inextricably linked and to recognize the rights of the musicians without recognizing the rights of dancers still makes the musicians incapable of playing what genres of music they wanted and having full freedom of expression so I think that was sort of the chink in the armor of the prior case, the Festa case that failed to result in the overturn of the Cabaret Law.

SK: Can you speak to the role social dancing plays in a city’s cultural life? Why it’s important?

AM: I don’t know if I’m the best person to articulate that. Honestly I barely dance myself. *laughs* I think it holds a deeply rooted role in a lot of cultures. And for a lot of people it’s a moment to just sort of let themselves go and experience the world less intellectually and more viscerally. And especially in a stressed-out city like New York that’s probably a good thing for them, a release that people need. If ever a city needed it it was probably New York and it’s absurd that New York of all places prohibited it for so long.

SK: I guess that about takes care of my questions. I’m wondering if there’s anything you’d like to add?

AM: I’m happy things worked out the way that they did. It took ninety-one years. It should not have taken quite that long for something so obvious to come about, but better late than never.

SK: Thank you so much for taking the time to speak with me today!

Thank you to photographer Destiny Mata (@destiny.mata) for providing these images from the January 2018 Punx of Color show. Catch the next show at Rubulad in March!

Photo: Punx of Color Photo Series at Silent Barn. Photo by: Destiny Mata

Photo: Silent Barn in the months leading up to the Cabaret Law repeal. Photo by: susan karabush