Myssi Robinson, Nattie Trogdon, Hollis Bartlett, and Noa Rui-Piin Weiss in conversation

The dancers bound into the studio and fall into repetition. They pick a move and then stick with it. Expanding and contracting, they string out into multiplying timelines. Some morph quickly as they get bored with the original movement and shape it into something more interesting. Others decompose their move over a longer stretch of time. As your eyes rove around the group, you can catch snapshots of each trajectory.

Sometimes the dancers meet up by accident. Sometimes you notice a person noticing, watch them puzzle out how to join up with another dancer without dropping their own task. Sometimes a few people hit the same rhythm at once and never meet.

This is “Stick with it,” a score that Nattie and Hollis have been researching for years. The idea is simple: do a move, then do it again, repeat indefinitely. It’s a score about finding your limit, persevering, and getting what you need.

Myssi Robinson: Did you have conversations about the mental/emotional/spiritual resilience involved in this score and how you might source from them? I’m curious about that in your own practice and with these artists.

Nattie Trogdon: At first we tried (unsuccessfully) to frame it as a task and it very quickly was not a task. It was a really frustrating practice that came out of a necessity to prove ourselves to each other… to prove ourselves to the world, prove ourselves to our relationship. We always joke that we don’t make work about our relationship, but here we are.

MR: It’s sourced from the tether.

Noa Rui-Piin Weiss: Can’t abstract that out of it.

NT: Yeah, this score turned into a piece that we showed in 2019 called Transmuting and somebody said “This piece is about your relationship” and we were like “No it’s not!!”

Hollis Bartlett: We were like, “We made this abstract work about persevering” and the feedback was immediately, “This is about your relationship.”

NT: We kept pushing ourselves inside of it and it wasn’t necessarily healthy but it felt like what we needed to do at the time. I literally remember laying on the floor sobbing next to each other because… it wasn’t just a task. So when we started sharing the score, I remember giving a disclaimer, “Emotions might come up, that’s okay, if you need to take a moment please do.” We wanted to provide care for other people that we didn’t give ourselves.

HB: We found care through this structure in a really odd way. The difficulty of the score meant we had to lean on each other more in performance. We figured out a lot of shit as partners, as performers, as makers, through this score for that piece Transmuting. And then it became something that we would check in on through the years. The pandemic hit, we did stick with it through Zoom

NT: Which was so hard.

HB: It became this communal thing. It was this–

NT: —longing. It became about loneliness and wanting to be near each other and holding on to this thing that tethered us together, that we could run around in our tiny spaces and skip and jump and scream and throw our hands in the air.

HB: So maybe, through those “Stick with its”, we knew that there was joy in it, we found a glimmer of hope. But bringing it to the students at Ailey, they immediately made a dance party. They found communal care, maybe because they were returning to touch and being together in space after so long apart.

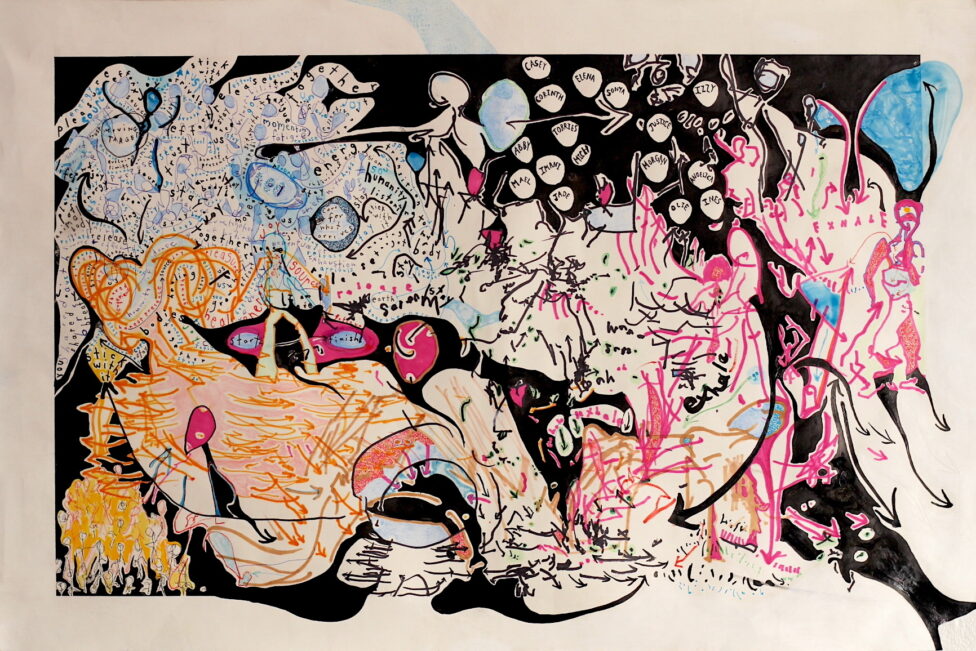

Image of a maximalist mixed media work on paper bordered in white. In the top left corner is a blue collection of differently designed words that flow into the torso of a figure drawn loosely in black. On the right side of the figure are names in white circles within a black void. Black arrows flow in different directions from the void. On the far right side of the work is a figure drawn in magenta marker lines and tiny red pen dots. Blue blossoms above their head and thick black arrows flow from their feet onto the white border. In the space beside the figure are magenta and black lines, sketches, arrows, and the repeating word exhale. In the center thickly outlined in black are the words start and finish outlined in blue and magenta, a magenta oval with a few black lines outlined in tan, and marks with the word exhale. Between the words start and finish are the legs of a figure that extends upwards. Below this is a multi-textured circle filled with shaded blue, magenta arrows, red dots, tan lines, and black that pours from each side of the circle, ballooning onto the white border below. The black fills the lower left corner of the work holding a clump of small black and red stick figures set in orange and yellow. Above the clump, a black figure with a pink head-like shape and a black arrow tail sits atop a defined black line. Orange arrows pointing in different directions against a pale red shade background the figure.

“That part is real,” one of the dancers says after the showing. They’re jumping, whooping, pulling energy out of thin air. This, after all the changes, all the work and the sweat and the speed. The unison is gone, they’re a mess again, together. Form gives way to function, is it efficient or inefficient to kick your legs at the top of a jump just to get through?

MR: I am thinking a lot about that moment of shared breath, going up and down the diagonal. It was like waves and waves of this agreement: we need each other to get through. Breath is the place where the body and the spirit come together. Feeling them meet in that place was so special.

Cohering into a group, the dancers break out of their explorations and fall into a heavy, fast unison. They shift from foot to foot, surging up the diagonal, whipping their hands across their bodies. Sixteen sets of lungs tap into one rhythm over and over.

The quick switch, watching the sprawling idiosyncrasies of the dancers meld into one move, one momentum. Imperfections? Dissonances? Cracks in the unison rise and fall, dancers revealing themselves and their habits. The subtle way a person bounces off their heel, or sinks deeper into a hip, or catches the beat a millisecond later.

MR: Witnessing the score over time, I felt them moving from a place of execution into personal expression. I’m aware of the training that asks them to direct the story in a specific way and I could feel that performative shell give way as the demand on their bodies grew.

HB: We’re interested in fracturing that shell–

NT: Performance self!

HB: And what do you see in those cracks. Through this structure of listening, they formed some beautiful bonds.

NRW: The performance shell–that physicality that emerges when you’re chasing perfection–is also a type of body knowledge, and especially in the context of the Ailey School is very useful. But, it’s not useful all the time. Considering the hierarchies of doing something “well” or doing something “to completion,” can we talk about the role of failure in this score?

Closeup of a mixed-media work on paper. To the left of the image, a thick black arrow points upward to the bolded words stick with it outlined in yellow and surrounded by uneven blackness. Black and orange arrows and lines cover the image and a light pencil shade of red flows from the right moving upward towards other words nestled among the orange lines in the upper half of the photo. The words, of different colors and sizes read : effort, evolution, care, stay, honest, go, joy, heal, fatigue and bodies. Along the bottom right edge of the image is a small oblong magenta half circle outlined in black.

NRW: That’s my main experience in this score: I do the move again and immediately I think this doesn’t feel good, I don’t want to repeat it. In two seconds, I’m like I’ve failed, I’m not good at dance, and I’m not good at the score, and my body is wrong. One of the students also mentioned that during the audition they were thinking “I don’t know if I can do what you want from me.” You are asking a lot of the students in this score, but you’re not asking for a specific thing, and that’s a difficult thing to reconcile as a dancer.

NT: Whatever your dance background, there is always something unachievable about it. We are constantly chasing perfection, correctness…

MR: the external.

NT: Right, and we often say that performance is simultaneously the most and least authentic versions of ourselves. People always say “There’s room to fail.”

HB: “There’s no right or wrong.”

NT: And everyone’s like “Yeah yeah yeah” and then you do it and you’re like “Oh no sorry that was so wrong.” Maybe this score is a way for us to work out that idea of perfection.

Left corner closeup of a mixed-media work on paper with a white border. On the left are small black and red stick figures in a yellow and orange clump. The figures are surrounded by a black background that fills the corner and balloons downward onto the white border, flowing around a collection of black arrows at the right edge of the image. Above the arrows is a semi-circle filled with red dots, blue pencil shading, tan lines and black definition. Orange arrows pointing in different directions against a pale red shade fill the top of the image and tan lines slope downwards on the left. A black figure with a pink head-like shape and a black arrow tail sits atop a defined black line that slopes in from the top left corner.

MR: Intuition is coming forward for me as a foil to failure. As their bodies are going through this journey, they’re making choices that are sometimes conscious and sometimes originate from a deeper place. If we can celebrate our agency and the miracle of our intuitive experience within community, then that is the success.

MR: I’m curious, do you ever feel a sense of failure in how you are holding space when you share these scores? And how do you navigate that?

NT: Cry! No, but there definitely have been times when I feel like we didn’t hold up our end of the bargain. Both of us clock it pretty quickly and then it’s this scramble to change. We have long conversations afterwards about how we can hold the space better, but I have to remind myself that it’s not always about us. People are trying to potentially undo a lot of trauma from their training and this score is pushing up against that in a way that can be difficult.

HB: I always fall back on the words of Nancy Stark Smith, and I’m paraphrasing terribly but she says, within teaching, she tries to model striving, so that the students can also get the sense that it’s okay to try and fail. We try to center research in our teaching…

NT: …to show that we don’t have the answers.

HB: …and we’re not here to give you our answer, but collectively we can figure something out.

MR: Right, how could you have the answers for their bodies?

NRW: A lot of dance training does say that though. That your teacher has the answers for you. I think that’s an expectation I’ve definitely put on teachers, like “why isn’t this the right answer for me?”

NT: And maybe if we’re coming in saying “We don’t have the answers,” it becomes very frustrating!

HB: We try to pose these containers or “impossible tasks.” Hopefully, by setting it up as impossible, we’re immediately inviting failure into the room in order to change our relationship to it. If nothing else, class space should be the place to fail.

MR: I’m bristling so much at the term failure because like… it’s all a miracle. I understand the cultural conditioning that depends on good and bad, but I’d love to reframe failure as being in a place of beginning, trying. I remember being a young dancer and getting introduced to concepts that didn’t sink in until years later. Let’s invite in a sense of timelessness as artists of the body. I hope that y’all [Hollis and Nattie] can hold that when you feel like you’re not getting to the students. That it may sink in later.

NRW: Some of these students may decide to pursue a super technical career and then in ten years be like, god I want to improvise.

NT: That is… maybe all four of our journeys here? I think that’s why it was exciting for us to be in this residency. This kind of rigorous conservatory training—although not Ailey specifically—is our background. Those forms are so ingrained in my body, and that deep message: You’re never going to be good enough. Most of my experience outside of school has involved excavating those ideas and trying to understand that I am so much more than my training.

“Stick with it” was this excavating, like “I can kick my legs but nobody cares about that.” It doesn’t matter if you have all the technique in the world or nothing, it’s about the hunger to move.

HB: We’re trying not to deny the training we and these students have, but reevaluate the value systems. A lot of choreographers rely on the assumptions that are ingrained in this mode of training, and we’re trying to shift what we’re expecting from the students. But if the students aren’t also making that shift, then it’s difficult to get the message across.

NT: And we all need time. It takes time to understand that.

HB: So the hope is that we at least planted some seeds.