Steve Paxton: . . . your lingering when Beau’s solo starts was long for me. I don’t know about Lisa because she…

Lisa Nelson: I totally agree.

SP: …often lingered longer than I wanted her to. Beau’s entrance, however, was fantastic. It was creepy, and wonderful, and serious. At that point, Megan, you were pretty active, and you did not give in to his entrance–you kept going. You were also performing to us, so you were dividing the stage. It was one of the high points of the performance last night, because it was so creepy, and yet not creepy because Beau wasn’t doing much of anything. Beau was slow, and on the side. It had a weight to it. Megan’s relationship to it was quite active, and that was good.

LN: Dangerous to like things!

SP: Dangerous to like things?

LN: Very dangerous because it’s very hard to repeat them.

SP: I would say repeat it. I repeated it.

LN: I would stay out of that territory. I wouldn’t have been able to do the dance if I was trying to repeat a whole relationship.

SP: The whole relationship needn’t be repeated.

Megan Bridge: Hearing you guys talk about that is really fertile. And also, of course, nothing can be repeated, really, but knowing that it’s a value that I’m not “giving in,” I feel like that language is really precise. That depending on where I am in the space, and where Beau enters, I might notice more or less when he’s coming in, but the idea of not giving in feels helpful.

LN: Not giving in is the whole thing. That’s the nature of our way through PA RT. I like the way it balanced direct attention; shifting attention from a kind of a peripheral, parallel universe space, where each of us are in our own imagined space with the other, into a more direct attention to one another, and direct touch. When Beau entered the first time, you took your time building up to being in direct awareness of him. When you settled right next to him there was an apparent shifting into very direct attention. You each had your own ways of shifting that attention, which was very interesting.

SP: Lisa and I have observed that you have a very strong duet. It is really kinetic. You have strong individualized participation within the duet structure. It’s really strong, it’s great.

LN: I assumed you knew one another, and liked to dance together. That was an assumption, and seeing the nature of your dynamic affirmed that.

MB: The duet is, of course, different every time we do it—from the amount of contact and awareness, to non-contact or non-awareness.

LN: Good!

MB: We always have had a strong chemistry on stage. Recently, we were working on this other project—this very sweet, romantic duet to Schoenberg’s Transfigured Night, with another company [Group Motion Multi-Media Dance Theater] in Philadelphia, and we were talking about our chemistry as performers and our connection. It’s sort of an infatuation.

Beau Hancock: An affinity that we’ve found in dancing together.

MB: It shows up in so many different ways. It’s exciting to have this open framework to explore that relationship, that affinity. It seems that was also something for you two over all those years; having a rich framework in which to explore all the different ways that you are together.

LN: We found it as kind of a measure of where we were each at. There was a definite change of the relationship over time. There was a certain tension between us in the beginning, and that morphed into something else over twenty-two years. A young couple moving into middle age–some of that tension got lost over time. Mary Overlie, who saw a lot of our early work, saw us perform in Vienna some twenty years later and remarked that she missed the tension. She had bonded to whatever drama she had read into it.

Lisa Nelson and Steve Paxton in PA RT. Sao Paolo, 2000. Photo: Gil Grossi

SP: In early performances I was concerned that our attention to one another not be a romantic duet cliché.

LN: Both of us avoided that.

SP: I had a habit of looking away from Lisa when I was in contact with her. Or to look away at the end, when a deeper look might be classically indicated. And to keep my pseudo-blind entrance going [Steve wore sunglasses as part of his costume for PA RT], to remain interested in where my eyes were, as a focus, so to speak. To let the touch and coordination with what Lisa was doing be there but not commented upon by the direction of my head. I was always bringing in an aside, like a thought for the space, or a thought for what’s going on in the wings,. Eventually that went away because I felt like I was just stuck in a form…

LN: …Stuck in a solution…

SP: …In a solution that I needed to get rid of because of the fact that it was constraining my performance, as opposed to supplying a freedom typically available to us. Eventually the freedom we had as young performers evaporated. After many, many iterations, you can’t help but find the same solution, and recognize the solutions that you’re finding. In a way, that provides secondary structures–by not taking the first solution because you recognize it. But even those secondary and tertiary solutions start to become recognizable.

MB: And then you’re in your head, and you’re not in the dance.

LN: Way too much.

MB: Is that why you eventually stopped doing PA RT?

LN: It took too much energy. There were photographs taken of the piece that we’d use for publicity, these iconic photographs. Iconic because we are the same bodies getting into similar predicaments. We’d check after and say, “Did you feel that photo?” That just seemed wacko, that even with all of the practice of not repeating, of each of us on our own, of staying with fresh strategies, it seemed absurd that there could be such a thing as an iconic moment, captured. I remember feeling like there suddenly was a lot of expectation put on the work and on us. When people used the images for publicity for our shows, they were hyping it, to get everyone to come see it, and that pressure was really dismal. I didn’t like that pressure.

MB: The content is so sensitive and of the moment, and of you.

LN: Most of the places we would perform PA RT were not English-speaking. I always knew that the experience for people who drift in and out of watching the dance and listening to music, were missing the text. Their idea of what we were doing could be quite sentimental without the added understanding of the text.

BH: I think that even for English-speaking audiences the text becomes a wash.

LN: And certainly if they’re only seeing it once.

BH: I’m still surprising myself with what comes through.

SP: It took me a year of listening to really get the story.

LN: Or the non-story. I don’t really listen to the text, the fun of watching on video afterward was to see the synchronicities of what was happening between us, not what either of us was doing, during a certain line.

MB: Did you record it every time?

LN: Every time.

MB: Every time, wow. Did you watch it every time?

LN: Not every time. It depended. We would watch it to get that crazy hit off of the synchronicities. And there were lots of them. I mean, lines like, He handled himself in the morning, is during my solo. I had to look out not to get set up for that. It was more fun to look out for not doing. Around the time of the line advanced practices we were often doing something that was just so crazy that I had to just try not to anticipate that line. It’s so virtuosic. There were a few of those I had to really have control over. On Every kid is armed, so where are you going? I would start to anticipate Steve’s entrance. I was just dying for Steve to arrive. A few times, he got lost in the house, and it was a very long time before he got to the stage. And I was thinking, “Where the fuck is Steve?” Like, “I don’t know, should I start something else?”

BH: I felt that way last night in one moment where I was waiting for—she had three—what is it?

MB: Three men have loved her, one a decade on average.

LN: That is the theoretic line of my return to the duet. But I always would try and…

MB: Play with it a little bit?

LN: To not be so obvious. I enjoyed what you did last night, you did something very direct. It has nothing to do with what you should or shouldn’t do, but it’s fun to track when I notice a shift from direct to indirect attention.

MB: The musical cue, three men have loved her, is so direct and specific. Sometimes I’m distracted and not fully participating in watching, and then it comes as a surprise and I just jump in and it feels horrible — silly, and really obvious. Last night, I was so involved with what you [Beau] were doing, I was already having a kinetic response. You were doing this rolling thing and I found myself doing it along with you. That brought me in and it felt really good.

When you first started working on PA RT, where was Robert Ashley in his process? Did this recording already exist?

LN: Well, it was this version [of the opera].

SP: They cleaned it up.

LN: They remastered it.

SP: Remastered it, and remastered it, and finally put out the CD.

MB: The black and white 1979 video that we have—it sounds different, but it could also just be the space.

LN: It’s the space and everything. Everything was lo-fi. Ashley gave us a libretto in ‘87 when he came and saw it for the first time.

MB: He didn’t see it until ‘87? What was he doing all those years?

LN: We did the piece once in New York in ‘83 and then we did in Philly, at The Painted Bride, just before doing it in New York again four years later. I don’t know why he didn’t come in ‘83, maybe he wasn’t in town. When he did see it, he really loved it. He came three nights. He wanted to see it over and over, to see versions, to understand them.

SP: His coming back to see the show again and again was the happiest moment of the relationship of working with his music.

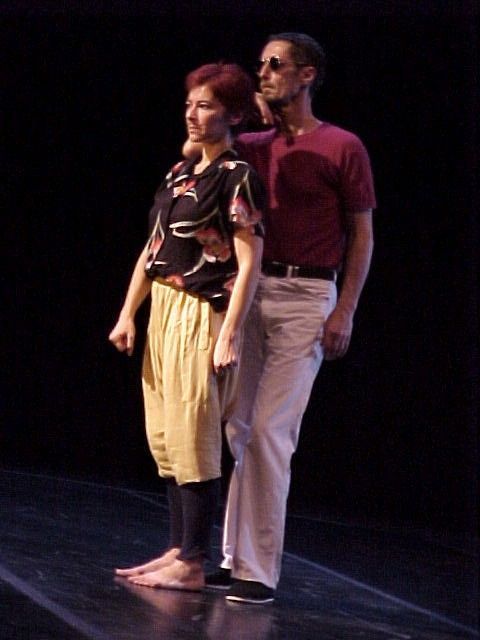

Megan Bridge and Beau Hancock in The Backyard, Lublin 2018. Photo: Maciek Rukasz

LN: Yesterday, Megan, you mentioned those three intriguing ways of looking at the process or approaches.

MB: Which we should credit to our friend David Brick from Headlong Dance Theater. David came to watch a run through last week. He actually watched the video from ‘83 while he was watching us.

LN: A live comparison!

MB: He was able to make a lot of interesting observations. What does it mean to re-construct, or re-stage, or re-do, or re-visit an improvised performance? How do you translate or teach that? The three different approaches that he thought of were 1) an open score where we are open to our own decisions in the moment and our own bodies and it is all completely new, and we are not necessarily taking traces of what you guys have done; 2) watching your performances and trying to channel you through our performance but in a loose, energetic way; and 3) learn the material. I mean, could you imagine? What if there was a triptych to this piece?

SP: Trisha Brown Company could do it.

LN: Yeah, but which one to learn?

MB: Tedious . . .

SP: What’s the ethical relationship to the original material which was not ever

anything…

MB: Set.

SP: …specific. How do you retain that changing mode that we were attempting?

MB: It wouldn’t be the piece at all.

SP: This is a philosophical black hole.

BH: Quagmire…

LN: The first one you described a little differently yesterday. The first one: where you would review whatever documentation there is of the made piece or the performed piece, and then just take off without any constraints.

BH: There is kind of a fourth that you’ve mentioned before in talking about this which is maybe aligned with what you are describing. It’s a bit like a text that’s been erased but the traces are there . . .

MB: A palimpsest…

BH: Writing a new story on top of this papyrus, which has been erased. But it’s still bleeding through, the original lines of script are still there.

SP: I love that word. Palimpsest.

MB: The formal definition is “a manuscript or piece of writing material on which the original writing has been effaced to make room for later writing but of which traces remain. Something reused or altered but still bearing traces of its original form.”

BH: It’s like those Cezanne canvases that have four canvases underneath them.

LN: That’s a delicious concept for a transmission.

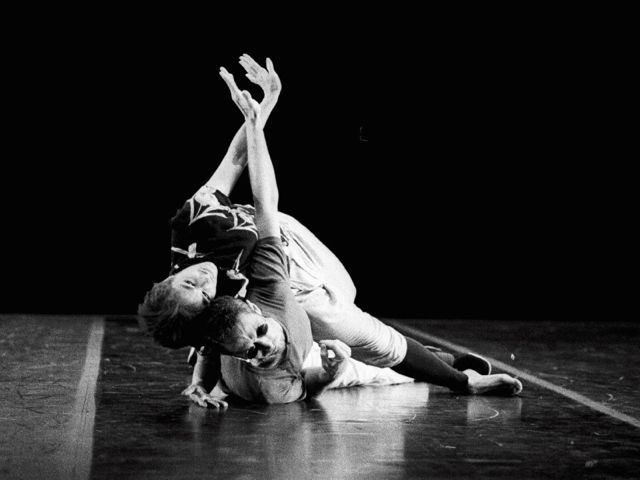

Lisa Nelson and Steve Paxton in PA RT. Sao Paolo, 2000. Photo: Gil Grossi

MB: When David watched the video and watched us, he gave us some observations about the differences in our movement, between our movement and your movement. He was talking about how both of us tend to be more shape oriented. In particular he talked about how Lisa’s movement has more of a careening quality and deals with momentum . . .

LN: That’s funny!

MB: I forget the words that he used to describe mine. But he was pointing out the differences, specific differences in our approach, our movement. And for me the first model of how to reconstruct this or transmit this work is that we are not worrying about trying to emulate your movement approaches at all. That we are just letting our own habits, tendencies, and real time responses to the music and the environment come through as they do in the moment. And then the second model is that we are not relearning specific movement but we are thinking careening, momentum rather than shape. We are trying to reference the kind of movement. It is always going to be filtered through the lens of our bodies and our experience, but we are actively making an effort to not just be in relationship to you, but trying to channel you.

BH: Then the second one would be — living in a similar qualitative world.

MB: Qualitatively trying to emulate or channel.

LN: Or taking something that you perceive about the environment that we are living in, and live in it. It’s interesting to talk about movement because that’s such a big part of the improvisational effort. That was, without any question, what I was challenged by in the dance. I had to make my own challenge—whatever I was working on in terms of my movement, which to me is as much “movement” as it is “attention.” With an appetite for something I can’t do, I’m always doing stuff that’s hard for me. That’s my own habit.

That’s what changed over time—the personal scores. I would love to hear what Steve was working on movement-wise. The way Steve worked or attended to movement was totally different than how I did. I was always looking at Steve like “What the fuck? What is he doing?” “How does he keep that up? “What is so absorbing about that?”

I was thinking about whatever movement things each of you are working on at the moment. So that was part of my curiosity. You bring your relationship, or your two-ness or whatever it is that is so particular that you can depend on, in a sense–you don’t have to invent a relationship. And then each of you, who moves totally differently—from totally different universes—which is also really good, I think. Over the years there was so much back and forth between Steve and I, we got much more homogenized.

SP: I wouldn’t agree.

LN: I think I got much more into flow, personally, over the years.

SP: Not my flow.

[laughter]

BH: It’s like cross-pollination.

LN: Well, not conscious cross-pollination.

So what would be the things that you see working on now? I’m very curious about what your base material is. There is always content—there’s always movement content. What do you chew on?

Megan Bridge and Beau Hancock in rehearsal, Philadelphia 2017. Photo: Julia Fisher

MB: When we first started working on this we talked a lot about the tension between composing and allowing things to arise in the moment and not worrying about trying to compose the arc. When we were trying not to worry about composing, we found ourselves constantly falling into our movement habits and patterns. So then there is a tension—or maybe a generative place—between what questions we are asking as movers and when, or how, those lead to solutions found in our habitual, go-to moves, which become kind of stale and uninteresting.

SP: Are they stale for an audience or for you?

MB: For me it can become uninteresting. And when I am uninterested, that probably becomes less interesting to the audience.

LN: Everyone’s got their own strategies for getting away from their habit—strategies for changing the channel. That would be opaque to an audience, a normal audience. It might make some strange break or shift of expectation.

SP: I saw that in last night’s performance. There were moments in which things seemed to be, I don’t want to say predictable, but expectable based on what came before. And then there were sudden breaks which I really enjoyed. It is in those moments that character shows, that characteristics show. It’s like somebody at a table behaving themselves and dining and then suddenly going “Oh, God, what a day,” and then back to it, that’s it. It’s like suddenly you’re confronted with a whole different aspect of the person.

LN: Ashley does that in his language, in a single sentence. The language I use is particular but I need to be following something. It’s all I need. I have to generate a little bit to discover what there is to follow at any moment, I can keep spinning that wheel, generating as micro-little as possible so that then I can follow. And as long as I am following, I am having a completely surprising time because I don’t know where it is going. Following, following, and so this kind of…

SP: Language…

LN: Exactly. . . language… What I say the meaning is does not matter. I’m either riding some sense of it in my body or I am just lost. Even though I hate text and really have only ever been involved with text in my own work with Ashley—I really don’t have any use for it as a dancer—all of my metaphors or scores, were about reading. So the activity of reading and sensations of reading, how I make sense out of something—the nonlinear thing of reading, you know: scanning, jumping, kind of bashing together meanings in a nonlinear way even though it seems to be linear.

SP: That quote we had earlier about the star. . .“Remove Star, Remove Thankless,” that’s what I have to do when I am aware I’m reproducing myself in a way I don’t like. “Remove leg…”

LN: “Remove repeat.”

SP: I think Ashley’s text is so interesting. It’s the most interesting, the most deeply interesting of all the stuff I’ve heard of his. He is always sparky but this text—somehow, something happened. I think it has to do with his constructing and deconstructing and then reconstructing and then this sad little voice that he’s got, you know just kind of accepting all this complexity and trying to go on and on and on. . . into this world that he’s making. I just love it. Last night when the music came on, I hadn’t heard it for a long time and I was really moved.

LN: Yeah!

SP: As I used to be moved in our frequent performances and I would hear it and move and go do it again.

MB: Exactly!

LN: Right.

SP: Here we are, this world has arrived again. So nice.

————————-

This research project led to the development of The Backyard, a duet created and performed by Megan Bridge and Beau Hancock, after Nelson/Paxton’s PA RT. The Backyard is a program of <fidget>, an experimental dance & music performance company based in Philadelphia, USA. This project was partially funded with support from the Net/TEN Foundation’s Travel Grant.