I frequently think about how to dance, how I choose to dance, how we choose to dance. I think about how my body is feeling, what I’ve trained it to do, why. I think about the privilege, the hours spent, the injuries suffered, the debts incurred. I think about the joy, the generosity, the persistence in the idea of embodiment. I think about the defiance bodies can carry; how a stage

is a place of possibility. I think about how the world doesn’t want us to dance, but we do it anyway.

“Capital-D Dance” is a term I’ve been obsessing over for many years. It means next to nothing but carries with it the authority and prestige titles and terms seem to allow for. What’s so capital about it? And, why? In unpacking my own understandings, even my zeal to self-label as one of these “Capital-D” dancers, I am writing, in part, in order to be accountable to what is being

capitalized (on) here. Capital is proper, it’s valuable, it’s prominent, it’s the center. But, while meaning can easily dodge rhetoric, the same does not work in reverse. Language is our primary meaning-making device as artists, as humans. Even in dance, language dominates; priority of understanding is given to artists who can orchestrate the flashy proposals, the enticing sentence structures, the quick-witted emails, the properly educated approach to grammar, the spell check. Language creates distinctions, sharpens separations, widens divides. Language, like dance, makes our stories replicable. It means narratives—however false, oppressive, savage—can, and will, continue. It means if there is a “capital,” there is also a “lower case.”

Language creates hierarchies. No, let me take that back. Language, in dance and otherwise, perpetuates and amplifies hierarchies. It allows them to exist in ways both glaring and insidious.

There is something about being a dancer—ok, sure, an artist—living in New York City—ok, sure, Brooklyn—in 2017 that seems sharply confounding. We are trying to figure out how our performance worlds can resonate as we fight for what matters, why it matters, and whose lives matter. As much as experimental dance is versed in evading the greater (white) culture in which

it resides—through the creation of alternate worlds, of futurisms, of “safe spaces,” of imagined realities that all become real in performance—there are also ways that abstraction or experimentation are used in order to escape honest dialogue. Vagueness, obstruction, obfuscation, disguise; ways to orbit around trauma or violence without ever landing anywhere. It’s the heat building inside the hamster wheel. It’s water circling the drain; cloudy and clogged.

Let me get specific. “Capital-D Dance” is a way to name the privilege of white artists while making it sound like something sexier. It’s a way to point toward dance traditions that are steeped in racist, ableist practices because those traditions stem from cultures steeped in those same practices. We know this. We need to.

“Capital-D Dance” is to be taken seriously (i.e. funded) and lauded (i.e. funded and toured). In this vein, technical proficiency is measured by its proximity to ballet. Serious dancing amounts itself to a rigor that is purely physical, muscular, sweaty. Impressiveness is measured by choreographic wit or a formal approach to composition…all of which is further measured by sweat and, yes, a proximity to ballet. I was (am) a benefactor of all that is “correct” in our Eurocentric dance worlds, where I had access to plenty of ballet training, plenty of white people; I am the stuff “Capital-D” dreams are made of.

Capital-D Dance is…classic, Dance Magazine, Doug Varone, funding, drop swings, problematic, Jiri Kylian, sociological, academic, whiteness, joy, Crystal Pite, cis-gendered, heteronormative, Sonya Tayeh, and/or whatever the “experimental” does not want to be.*** You know this. You need to. Ballet is what you do to train; modern dance is what you fall into when that doesn’t work out because you’re too fat or queer or angry. Choreographer is what you become when you are done being a dancer; dancer is what you are as you strive to become a choreographer. There is always a lot of striving going on.

I want to have a tea party with all the dance makers who identify as formalists (abstractionists, conceptualists, etc., you get it) and listen to us talk in circles as the tea chills and the scones stale. What a way to get to spend an afternoon! What an interesting, frustrating conversation – dance is the most unlanguagable of all art forms, after all! The bastard! No wonder everything

feels like burnt toast on that day you accidentally overslept. Dry. Fatigued. Gloomy. Committed.

In the dance communities I have been permitted to move through, there is activism, subversion, an urge to intellectualize everything over experience anything, skepticism. There is a lot to do and very little time to do it. There is attention to skeletal systems, somatic systems, neurological systems, endocrine systems, economic systems, public transit systems, educational systems, communication systems, social media systems, electronic systems, manual systems, systemic systems. We live, sweat, eat, complain, and strive in community together. There it is again, the striving.

I can’t remember who or what exactly made me aware of the term “Capital-D Dance.” A cursory Google search points to its use but, sadly, not its origins. Still, I can’t recall the exact context, where I was, what it referenced, why I cared. What I do remember is how I felt; the immediacy of intrigue. The well-built façade surrounding the concept was enough to pique my attachment—

beauty, safety, accomplishment, fame. “Capital-D Dance” circles certain truths that seem near- absurd to covet inside the knotty traditions of experimental dance; not because those ideals aren’t real or haven’t become understood as “real,” but because the concept of capital-anything in dance is a false equivalency. At the risk of sounding ridiculously obvious, there is no capital in dance. At least not the kind that provides generational wealth or makes you the beneficiary of Ivy league degrees or allows you to own lavish properties that you may or may not ever live inside of. In dance, and as a dancer, you don’t attain capital, you are capital.

We are. We are capital and, when forced to use yourself as that very currency—even inside the capitalist-resistant practices dance and performance think themselves to work within (everything ranging from barter economies to straight up labor exploitation)— the notion that “Capital-D Dance” is something to strive for quickly disintegrates. Dance cannot render itself exempt from the culture; the reality that separates those who get to enjoy this capital, and those who are made to suffer for it. The reality that spells out everything in terms of its proximity to whiteness. The reality of who, historically, has had access to capital (and through what means). The reality

of who, presently, has access to capital (and through what means). The reality that capitalizing on anything comes at the cost of anyone who is not a white, able-bodied, cis-gendered person.

And/Or…The reality that capital is always a finite resource. Eventually, we are left with our humanity.

***I posted a Facebook status asking what the term “Capital-D Dance” meant to people. Some of those responses are compiled here.

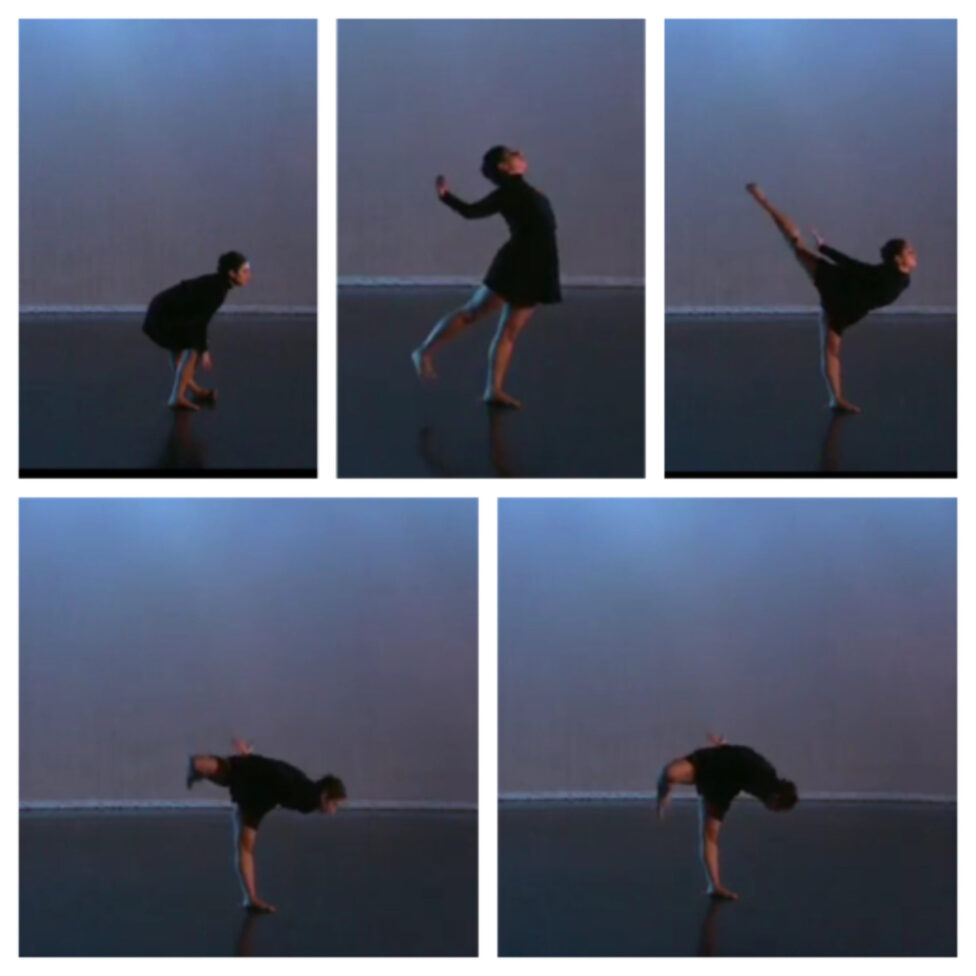

Karen Bernard, Poolside, Photo: Kathryn Butler