Biba Bell: Hi.

Richard Move: Oh my goodness, where should we begin?

BB: Because this is your twenty year anniversary of the Martha@ performances and performing as Martha Graham, I’m wondering if you’d like to start with that. I’m curious if we could talk a bit about the inception of the project. Or, of this body of work. This substantial body of work. Is that something you’d want to recount from this moment?

RM: Sure. Are there specific aspects? Or, I guess the readership doesn’t know all of the details…

BB: Yes. I thought you could provide some background.

RM: Yes! Well, as you know the project began at the wonderful space, Mother, in what was, at the time, the real, original Meatpacking District. And really it was just us and the restaurant Florent, at that time in the Meatpacking District – we were sort of the cultural hub there. It grew out of a one-off evening at the club space on our Tuesday night, with our Tuesday night event which was Jackie 60. And each week we did a different theme with different decor, and different performances. I very much wanted to do a “Legends of the Dance” evening, so I proceeded with that. I called the evening “Acrobats of God” after a ballet that Graham made, one of the last ballets she performed in. That was my first moment with Martha in my body and mind. It was very well received. I had a bit of trepidation, in terms of thinking that perhaps these were little known figures. It turned out to be the opposite. It quickly revealed itself to me that audiences could relate to Martha insofar as they could identify within her this kind of quintessential diva, like a Diana Vreeland was to fashion and Maria Callas was to opera, perhaps Betty Davis to film — this great pioneering spirit — It was a great success with a positive response and perhaps most importantly, it sparked the desire within me. This realization of an incredible life and body of work to explore in a performative way through dance and text. We — Janet Stapleton and I — decided to make it a monthly series. As the name of the space was called Mother, we named it Martha@Mother. The first event was in the fall of ’96, so ’16 –‘17 is our 20th anniversary season. We hit the ground running with an incredible audience at the very first event that consisted of performance goers, dance aficionados, curiosity seekers, artists across disciplines, and also included some early Graham dancers in the audience: Stuart Hodes, Bertram Ross, rest his soul, Linda Hodes, Mary Hinkson, Matt Turney, Yuriko. It was amazing. Taking the stage in the series official, Martha@Mother, I understood the largess of this, and that there was some kind of need, it was fulfilling some kind of need in people, and in myself. That’s when I rolled up my sleeves and dug into it as a primary artistic concern and project. As you probably know, before we opened we received Cease and Desist orders from the lawyers representing the Martha Graham Entities, which consisted of the school, the licensing of ballets, the company itself. That became a press item, before we even hit the ground running with our first performance.

BB: It became a press item in what sense? In the sense that it vaulted the publicity of the project?

RM: Yes! Yes.

BB: Okay…

RM: Yes. We had press before we even opened the first show. I often thank the Martha Graham Entities for providing us with that publicity, to generate an awareness of what we were doing before we even opened. But, of course it was also anxiety inducing, and that’s when we countered with this notion that we would not change the name. They didn’t want us to use even the first name Martha, which of course is ridiculous. We offered the disclaimer that “This event is in no way connected to or associated with the Martha Graham Entities.” We began with that and it helped us in a great way and as a result. I became enmeshed in this notion of copyright and legacy and the virtually real, recreation, reconstruction, these super interesting and very loaded questions. Obviously, the reality of free speech, cross-gender instantiation, what is parody, what is homage. So, I think from the get go, these issues, which are very much the forefront of dance and performance today, became glaringly transparent in what I was doing or in what we were doing. We proceeded and began to accrue in momentum in terms of the ambition of the dances I was reconstructing— I’m up to close to thirty of them now, which is staggering, and the number of dancers… I went from two dancers and I think we had up to twelve on that Lilliputian stage. The format was kind of a nod to vaudeville and Graham’s days as a big vaudeville star. Which, of course, was a “variety show” format, with the likes of miniature ponies, trained parrots and Graham performing her Denishawn solos. I created this vaudeville like aesthetic and program, which featured Graham in monologue, and Graham in dances with her company with my synoptic distillations that I aim to capture the essence of a dance, its spirit, its moment of highest drama. I could go into that with more detail if you like. But the format was Martha Graham, as if she had never died, hosting this dance-based variety show where she was introducing to the world, former members of her company, such as Merce Cunningham, Stuart Hodes, Mikhail Baryshnikov, and also presenting to the world, emerging artists. We were one of the first people to present, to a broader dance and performance audience, Julie Atlas Muz, for example. We had Basil Twist before his large scale productions and the more large scale exposure, that he then came to enjoy and deservedly so. Everything from the most emergent to the most legendary with Merce, Misha and Yvonne Rainer. Martha’s premise is essentially that she is the mother of it all, and I don’t think that’s at all far fetched, or requires a leap of the imagination. She sees everything through her lens, her cosmology, her world view, which she’s very much the center of. I think the humor arrives through this notion that she was the egomaniacal, narcissistic living legend who did everything first. Again, it’s not such a stretch. I think there’s an element of humor, and she had a kind of humor. One of my favorite quotes —there’s so many — when asked to respond to the postmodernist concept of the decentralization of the stage space, Martha simply responded with, “The center of the stage is wherever I am!”

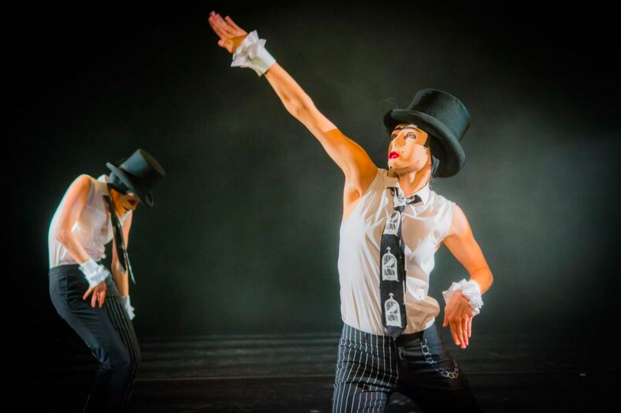

Richard Move as Martha Martha@20. Photo by JulenPhoto

BB: Ah [chuckles].

RM: So there are great, great quotations and great, great quotable quotes that I cull from films of her speaking and the volumes that have been written about her. These dance greats who were the second generation of Graham dancers. Dancers who began with her, say in the forties or so, began, not only coming to the show, but sharing stories with me. I’ll never forget Bertram Ross came to the show and one of the first performances. His only note for me is that he felt that I needed a more blood-red lipstick. Which was so interesting because at that moment I realized that I had been looking almost exclusively at black and white documentation.

BB: That’s so interesting.

RM: So that kind of detail was so important to the development of this persona.

BB: Yeah, there’s a lot that can be, that little anecdote actually, I’m thinking about, thinking through a number of different contexts, going back a bit, also this question of before you premiered that you had this cease and desist order, that there was this turning over, or a distillation of the archive itself too, the fever of it becomes apparent. I’ve always had this sense, there’s a lot of writing about it, but in terms of the Graham legacy there is a question of extreme fidelity to the technique, to the way in which things are performed, in terms of replicating Martha, and this question of a living archive in terms of this need, the need for you to do this was not just a singular need in your sense but it was also, it sounds like, a communal desire that moved across people who knew her but also this desire for there to be a matriarch in the room, bringing people together and continuing to produce while also honoring a kind of legacy.

RM: Yeah, absolutely. I think you really hit on the chord that we struck with this sense of community overseen by this matriarch, by this Grande Dame at the top of her form, where she had achieved greatness and this kind of fame, and this legendary status that she enjoyed in the latter part of her career, which then, of course, unraveled, largely in plain view of the public. But, the Martha of the Martha@… series has been at the top of her game. I like to think of her, perhaps in her late fifties, where she maybe looked like a thirty-year old woman who was dancing extraordinarily powerfully. Certainly within her most loquacious and eloquent, oracular, high priestess self with a simultaneous generosity and a warmth and this kind of embracing of this community that she helped to produce. There was definitely a community that galvanized around her for the series. It grew exponentially and very, very quickly. I believe people felt enveloped in her and all that she, with a capital “S”, stands for, which is an uncompromising rigor and commitment and dedication to one’s art. Art that is, in no uncertain terms, a higher calling. Martha equated the moment of creativity as the moment — as the driving force of god that plunges through her — this religiosity of what it is to be a dancer and what it takes to become an accomplished dancer. One thing that also happened very quickly is people at the top of their game in dance and performance would say things to me like, they’d never really taken the time to consider Graham, or made the effort to really understand Graham, and that somehow the performance opened the door for them and soon I found myself giving recommendations of things to view, things to read. I very quickly became a living archive. I became an attractor. All kinds of amazing things would happen, like that note form Bertram Ross. And Linda Hodes — co-artistic director of the company from the late ‘60s through ‘91 when Graham passes — even into the years beyond Graham’s death, offered her services to me and to us, my group of dancers. She became our rehearsal director, bringing me all that incredible knowledge. She entered the Graham School as a child in the children’s program, and then by her late teen years was in the company, and then soon became a soloist and principal and then Martha’s right hand, right arm. Oh! And then things would also just happen out of the blue, like I’d open the mailbox and some journalist in Colorado had sent me a cassette tape of the audio recording of an interview he did with Graham, close to the time of her death. I started to accrue this aural history, herstory, but also these objects that were precious to her, like a Halston caftan, handmade especially for her for an opening night gala closer to her death, all of these treasures. Not long before the company was headed toward bankruptcy, with their own legal battles and then suspending operation, it became clear that the school was going to be demolished, the townhouse at 63rd street was going to be demolished. At that moment my dancers, and even others who didn’t work with me, began to smuggle things out of the building for me! I became kind of the archon in a way. It was just extraordinary. We just kept growing and growing and growing. And then, the Mother space was lost to gentrification, after about four years. We then went from accommodating perhaps an audience of 100 to125 people maximum, and then we sold out the 1,500 seat Town Hall! It went from the Mother space to Town Hall! That’s kind of indicative of the kind of growth and how our community was growing.

It’s a beautiful thing, and that continues right up till today. As a matter of fact, I just got this amazing invitation from the Gardner museum in Boston to, I was going to use the word recreate, but there isn’t any substantive documentation, of a dance she made called Immigrant, in 1928. And they came right to me, with, would I be interested to create, or recreate, this dance that has no documentation, other than the performance program.

Richard Move’s XXYY. Pictured L-R: Catherine Cabeen, Richard Move, Katherine Crockett. Photo by JulenPhoto

BB: Can we talk about that, because you said in the early Martha@Mother events you would recreate her works and I’m curious, going back, reflecting on that moment you looked mainly at black and white imagery and all of this. Then finding this essence and drama of, as a kind of arch or maybe the architecture of these works. Can you talk a little bit about that process, how you parse, how you intuit, what is that galvanizing of the archive itself as it stands but then also really fleshing it out, bringing into vibratory color…. What is your process like for that?

RM: Well I think, turning my head to parts of what we’ll be doing with our New York Live Arts season and Martha@20, I think one of the biggest points of entry for me, and I think this is clear, I hope this is clear to our audiences, a point of entry for me is always through Martha the person, the persona, the dramatist. She called her work dance-plays. A point of entry is where she was at the time of creation, psychically as a woman, as a creator, what was happening politically, socially, what she was doing creatively. For example, our version of Cave of the Heart, is based on her choreographic notes to herself about this plot. Everything in that dance leads up to Medea’s dance of vengeance, where she is devouring the serpent, and the first title of the dance is called Serpent Heart, and it was made in 1946. Her large, oversized, hard copy notebook that was published in ‘70 or ‘71. I’d have to check that date, because I don’t have it here, but at the office at the University. So, in that restaging, let’s call it, I don’t even acknowledge the other characters in her ballet. I believe the essence of that work is Medea’s dance of vengeance. So, I have set that to Martha’s own words, as they appear, in her giant notebooks that were published. Her choreographic notes for herself, one would presume for her eyes only, before she agreed to have them published, of her documenting what the solo is. It’s the crux, it’s the heart of Cave of the Heart. I have set it on one of my great dancers, who are former or present Graham company members. A dance that is an extremely difficult, challenging and all consuming, exhaustive solo of just several minutes, set to Graham’s own words, and Graham’s own choreographic notes. It is the essence of what she is imparting dramatically in the solo. So, I like to think in about four minutes, we embody what Martha had in mind for that ballet, for the central moment in that ballet which is Medea’s dance of vengeance, devouring this snake. I was just thinking of this amazing quote, there was an old woodcut in which a woman is eating her own heart, and the title of that woodcut is Envy. She had this masterful, unparalleled way of going right for the jugular of the human condition. And, it’s that jugular that I’m trying to impart without any of the trappings of the rest of the ballet. For example, another piece we’re doing is my rendition of Episodes, which was her collaboration with Balanchine and New York City Ballet, when they both choreographed to Webern. There is this amazing recounting of it, and interviews, and different texts. So, I culled together this narration based on Graham’s words, Graham’s notes, Graham being interviewed and also biographical accounts of this encounter of these two towering figures. Which also, one could say was the moment where Modern Dance was literally given the same stage as the Classical Ballet, and the only time these towering figures were to unite. But, their relationship was very fraught. What I did was condense and conflate it, both Mary Queen of Scotts, which was the subject of Graham’s Episode(s), and Graham’s own story of collaborating with Balanchine, being invited by Balanchine to create this ballet, and this kind of martyrdom. So, I hope that in, the five minutes or so that this dance takes, I impart to the audience the historical context of this moment in dance history, in 20th century dance history, in the meeting of these Greats, and also the drama surrounding their “collaboration.” And, also the beautiful poetry and drama of Graham’s dance play of about Mary Queen of Scotts, the choreography itself, that historical context. She becomes another of Graham’s tragic heroines.

BB: Yes. Absolutely.

Richard Move’s XXYY. Pictured L-R: Katherine Crockett and Catherine Cabeen. Photo by JulenPhoto

RM: I think that’s how I go about it. These are central moments in her narrative, her life’s narrative, the narrative of her body of work. Most often, my point of entry into my restaging of the dances, is first where she was at the moment of its creation and perhaps why she created this. Her works very much mirrored her personal life. The early work such as Heretic, that was both her embodiment as an outsider, as this woman forging an art form, and it also spoke to the larger social and cultural issues of the time, industrialization and man vs. machine. And then, Erik (Hawkins) arrives in her life and then there’s this great interest in Jung and Joseph Campbell. These archetypal figures and the hero’s journey. Graham becomes ensconced in Greek mythology, the human experience of these dance plays, so that’s the point of entry.

BB: Can you talk a little, as you’re coming into, as you discuss Graham and her works and this and her history… you’ve really, through time become an incredible expert of her, both in terms of the research, but also the act of performing her, and you, and the blending and blurring and layering of persona in that respect. I’m wondering if you would talk a little about the kind of growth or evolution or… how your relationship to the act of performing Martha has transformed, or [how] has it through time to where you are now in the present with this work.

RM: Sure… well, I think it’s perhaps first important to note that it’s still in process. I have kind of codified a way of preparing for a performance. It’s more formal in terms of what I do to prepare physically and vocally than perhaps at the beginning. I find it less self-conscious, if you will. I’m able now to submit to becoming the other. And I do feel kind of filled with something, filled with her, when I perform. I feel like we meet somewhere between the ritual of the make-up and the hair, and the beautiful replicas of her costume that Pilar (Limosner) makes: that there’s definitely a transformation, and a meeting of her, and I feel very filled by her. I believe in some way, I’m also imparting something of myself in these works, and my own worldview, perhaps sympatico to her’s in many ways. One of the elements that has been so wonderful with this twenty-year odyssey, twenty years and counting odyssey, is I’ve been allowed through this being an attractor, to delve deeper and deeper into this character-study. It’s so interesting because the last five years for example, and I’ll go into some specific examples, have been the richest terrain for me. The 92nd street Y unearthed this reel-to-reel audio recording, of Graham in conversation on stage, (with dance critic Walter Terry), at the 92nd St Y in 1963, and they immediately contacted me with this discovery. I was awe-struck, and then compelled to bring it to life, again. Thus was born Martha@…The 1963 Interview, where the great Lisa Kron portrayed Terry, and we staged the text verbatim. Then, I gave myself the freedom to imagine what Graham was seeing in her mind’s eye, and even what she was hearing, when she discussed her great roles. They come to life in her imagination through the bodies of Katherine Crockett and Catherine Cabeen, some of her signature roles, from Joan of Arc, to Medea, to Jocasta…That was super fascinating because that was the first performance in which a more vulnerable and fallible Martha came to the stage. In the interview she loses track of her train of thought several times. It becomes very tangential. And it is Terry that needs to steer her back. She’s as oracular and poetic as ever. There are allusions to her impending retirement. There are allusions to what she calls her “first death,” when she no longer was able to dance. She referred to that a dancer’s first death, when the once acutely trained body will no longer respond as you wish. So we have this, I would guess one could say a more human, Martha. She steps not entirely down from Mount Olympus, but steps down a few thousand feet of elevation. Shortly after that, durational performance came to me through “20 Dancers for the 20th Century” at MoMA, and then being given the entirety of the Asian Civilizations Museum in Singapore as a setting for my Graham to perform a durational act, where I kind of compress the Greek heroines for quite some time in this enchanting room of Asian antiquities. This durational aspect allowed me to then go a lot deeper into my understanding of the technique and dancing as Graham. I think the evolution is largely attributed to this notion of what I’ve become an attractor for. In other words I haven’t sought out these ways of deepening my own understanding of her and my performance, they’ve come to me through these amazing opportunities. Then I’ve kind of dove in and brought them into, into realizing them in another way, that has enabled me to understand her more profoundly and understand my performance of her more profoundly, or in a deeper way. Did that answer your question?

BB: Yes, absolutely.

RM: Oh great, great.

BB: The durational element was something I thought of when you were talking about the solos and a kind of distillation towards the essence of the dance. To be able to get at it in an immediate sense. I imagine it’s almost like a plunging into it. But without all of the steps that might lead to access the state or part of the narrative, I’m thinking of the Cave of the Heart story that you told, and that is really interesting. I imagine this almost pulling apart or this opening up of a kind of compression and the density of that. The way in which it would deepen your relationship to her, ultimately.

RM: Yes, absolutely. We plunge. It is kind of a diving in, a plunging in, not only with Medea, but also with Mary Queen of Scots. Mary Queen of Scots is going to her execution in my rendition. Jocasta, in our staging of Night Journey, is at the moment of the realization of what she called the crime against humanity or against human life and falling in love with your son. It leads the tragic figure to take her own life. And then there are the other elements of the restagings. I don’t use Graham’s music. Some of them are set only to her text, whether I deliver it live or it’s recorded. Some of it is set to a recording of her own voice and that’s the scene for one of my restagings, and then I work to find music that perhaps again captures the essence of the music that she was using. So I like to think it’s both honorific and true to its source, and then also becomes its own new object. I like to think it brings it into the contemporary moment, which I don’t think is difficult with Graham, because I do believe they’re timeless themes, or universal themes, and things like a love gone wrong, jealousy, revenge, these are timeless and universal.

BB: Yes.

RM: It’s a really interesting thing; they’re once tied to this historical moment, this epoch right? And then at the same time, completely liberated from them.

BB: There is simplicity, the term reenactment is sort of impossible, it doesn’t work, it doesn’t do the work in terms of thinking about what you’re doing. There is the kind of didactic element that you’re talking about, transformation in relationship to… I think about your personal transformation as a performer but then also the way that this work is brought into a living space, and brought to terms with the contemporary.

RM: Yes, yes, very much a living space.

BB: Can we transition a little bit to talk about your piece XXYY?

RM: Sure!

BB: I suppose there’s a way to transition. Does the Martha work have a fluid relationship into your other bodies of work or do you think about it as its own thing? Would you talk about your process outside of the Martha work?

RM: Sure. Well I think a lot of what I’ve made, springs from research, springs from historical figures and moments, and then I bring it into my own life and my own artistic life. With XXYY, I think of themes of gender, I think of this notion of gender fluidity. For instance, it’s so interesting because I don’t perceive my becoming Martha as a leap. I believe she might be what I consider being the female part of me. A part of most everyone, on some level. So, I think different bodies can take on different aspects of gender. I’m very receptive to that. I wanted to, with XXYY, kind of dive right into that, What is that fluid space between the binary of male and female? I conceived the piece with Alba Clemente, a good friend and a great artist, a very interesting costume designer and interior designer, and we understood we had this common interest, in this fluid space in between. This piece was generated first from our mutual interests and in conversations, and then after her first costume renderings. Playing with these kind of archetypes again, expressions of male dress and female dress, etc. It was so interesting because this piece began with some beautiful drawings and costume renderings before anything else took place. I’ve always been a bit obsessed with Alessandro Moreschi, the last castrato of the Vatican. The voice is arresting, it is operating on some other plane entirely. It is also a sad voice. It was written that Moreschi sang with a tear in each note. I think it must have been an extraordinary difficult life, because at Moreschi’s prime, the Pope outlawed the practice of the castrati, which had been a centuries old tradition at that point, in Catholicism, within the Vatican law anyway. Alessandro was in exile within the walls of the Vatican. It’s a fascinating life to ponder, and there really isn’t that much biographical material except several early recordings. So, he becomes the first castrato to make solo recordings and it is particularly fascinating as he was the last Vatican castrato. I was very fascinated and I had this voice in my mind and some very beautiful, almost Commedia del’Arte, Pierrot-like costume renderings by Alba Clemente.

Then, I found this incredible book, Autobiography of an Androgyne written by Ralph Werther, who lived under the name of Jennie June in New York City at the turn of the 20th Century. It was an incredible life. Androgyne, or third sex, was the only terminology in operation at this time, I think now we would understand Jenny to be a transsexual woman, but we didn’t have this terminology at the time. Anything perceived or misconstrued as cross dressing was illegal, anything perceived as same sex sexual encounter was illegal. This is an invisible life made visibly visible by this great, great autobiography of this human who lived on the margins of the margins in New York City’s underworld. It was a battle to survive. There were brutal beatings, blackmail, robbery and assaults of every kind. Ralph Werther, Jennie June, was documenting their life. It’s a cry, a cry for understanding and empathy. The goal, Jennie June makes it very clear, is that she hopes that her autobiography will generate an understanding, an awareness of the androgyne, or third sex, so that the treatment of these creatures would become more empathetic and that there would be more of an understanding and awareness. The medical doctor who published the book was so, so brave. The Medico-Legal Journal, thought it was important enough to publish, only available for medical professionals, clergy and lawmakers. It was not available to the public. So, it’s fascinating. The androgyne and the castrato are living at the same time on different continents, so I feel somehow they’re connected. Talk about marginalized and outlawed, the last castrato in the Vatican and the androgyne at the turn of the century in New York. I realized that these two figures needed to come to life and be given a voice. Then, of course I feel somehow connected to these characters and empathize with them and imagine their lives.

Richard Move’s XXYY. Pictured L-R: Richard Move, Catherine Cabeen, Katherine Crockett, Photo by JulenPhoto

Before we ever went into the studio and started developing the material and discovering this piece, I had this amazing text to work with and these amazing songs to work with, and these visuals, with the costume design. So, it was all deeply informed by reading, listening, conversations, and then into the studio to find a way to dramatize this through movement and text from the book, to capture a kind of an essence, of an interpretation, of these two historical figures that resonate very much today, unfortunately. This life on the margins, particularly for transgender and gender nonconforming people, is very much a life under threat or a life under siege now, even in New York. Different statistics are very, very dark for this segment of the LGBTQI community. The percentage of transgender and gender nonconforming people who are homeless, live in extreme poverty, who have experienced workplace harassment and discrimination and who become sex workers. Murder rates are astronomically multiplied in this community, and I’m speaking of right here in New York City, so one can only imagine what life would be outside of a major metropolitan center. We’ve come a long way, but let’s not forget same sex marriage, for example, that’s so recent. Our current administration. I think people are rightfully anxious about whether the few existing rights and laws protecting these communities remain intact. I think the androgyne’s life is very much resonant today, the life on the fringes, a life on the margins, perhaps a life misunderstood and life under threat. And then I feel like the castrato’s voice kind of embodies this liminal space. The challenge becomes, how do we bring all these ideas to the stage. My collaborators, Katherine Crockett and Catherine Cabeen (I call them the K/Catherine’s), come to, again, fluidly traverse these figures. They deliver text as the androgyne. Perhaps I dance solo to the castrato. But, then these morph and merge, and twist and turn, in and out of each other throughout the piece.

BB: The characters themselves become fluid amongst the performers? Is that what you mean?

RM: Yes! Yes, and I think representation of gender, is representation the right word? The imparting of gender. There’s a fluidity in the vocabulary, in the personas we embody, or inhabit us, through the text, through the choreography—

BB: I’m thinking about representation, the right word, I’m thinking the kind of… [Judith] Butler talks about it as kind of approximation, approximation in terms of performance of gender, there’s a kind of approximation speaking to a spectrum of possibility and also a kind of shiftiness.

RM: Yes, shiftiness? Did you say shiftiness?

BB: I did, I did.

RM: Yes. Approximation is an interesting word, representation I guess feels a bit shallow. I think the Katherine’s and I have access to a gender fluidity. I think we have access to an empathy with the androgyne, I think we have access to the tear in every note of Moreschi’s. So, the three of us together have created this thirty, thirty five minute work that is at once both tied to this moment in time, at the turn of the 20th century, but also a very contemporary story as well with very contemporary themes. Now that I really hear myself talk, I’m much, it seems, working in a similar way to Graham. The pouring through books and discoveries that she finds through reading and discourse with like minded artists and philosophers etc., taking copious notes and sometimes finding costumes at the last moment, sometimes drafting them at the beginning of an inception of a work. I think I work in a similar way, except I haven’t codified a vocabulary, of course. No one, I guess you could say, has at the level that she did. No one is anywhere near that, particularly myself, and I feel open to exploring a vocabulary in order to bring it to life. I am creating in a similar way, with almost an obsession with these figures, whether obscure or well known, and then bringing them to life. But, I do feel like I’ve been very interested in the underdog. You know I had a similar obsession with Mendieta.

BB: Yes, I was also thinking of your project Whatever Happened to Ana Mendieta?

RM: Yeah! It was a Eureka! moment for me when a friend brought me to the Whitney for a retrospective. I admittedly knew nothing about her, and I didn’t even know she had died while I was looking at the work. I kind of, I was taken up, I just was completely taken up by the work, and it spoke to me in this primordial way I started researching all I could and then I became obsessed and felt like I had to bring her, her story somehow to life. I wanted to recreate her great works and recreate them in a faithful way, but again try to capture their essence, you know getting muddy, building silhouettes in the sand and in the rock.

BB: It’s really fascinating. I feel like we should probably wrap it up soon, listening and thinking through all these different elements, the way you’re working with historical document, the way you’re working with these bodies of work, and I think body is really so important because it’s through your body ultimately. I suppose the word haunting, or hauntology could be one that would be used within a sort of performance studies context… It’s almost like there’s also a way, a mode of catching the spirit, which is within a religious context a common term, but the way in which there’s a visitation or vessel, or vehicle also, that is about a particular subjectivity that can potentially be mined through these archives. Also the way in which you’re moving it and working it and bringing out these fluid elements, it’s not resting or having a kind of fidelity to subjectivity. You’re working through that in a really, really interesting way. These are all observations but the way in which, there’s a ghost, these ghosts in the room that as artists or, going back to that pivotal moment of awakening with respect to copyright and the importance of that conversation within the artists’ community, within dance, within performance, bring up ideas of affiliation, of inspiration, of a kind of collaborative process through time and across these absent bodies, presences and these absences.

RM: Presences, absences, collaborative spirit, intuition. An almost outcome blind following of one’s intuition. You know I also got cease and desist order from the Mendieta estate. Again, this kind of perception by these legal entities that I had crossed a line. It also happened with Edward Albee when I played Martha in Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf, in New Mexico. [laughter] It’s fascinating! It is fascinating. But anyway, onward we go.

Martha@20

Martha@20

XXYY

XXYY

XXYY

Martha@20

all photos by JulenPhoto

Richard Move as Martha Martha@20, Photo by JulenPhoto