Note: This essay analyzes and evokes the making of a specific dance through descriptions of context, questions, activation-scores, and the OBSERVATIONS of a witness (Veda Carmine-Ritchie) in rehearsals.

I write as a Russian artist. I write from the side of the aggressor, from a position of guilt and responsibility for the crimes that my government has committed.

These are the questions that form the basis of my inquiry at the start:

- Is it my country’s war, or that of a gang that came to power through fraud?

- Did Russia do this, or was it done to her?

- Are Russians pawn-like hostages to their leadership, or are they collaborators? Are they citizens contaminated by the radiation of state-sponsored media?

- Are we conditioned to be apolitical?

- Is there such a thing as “we” Russians, or are we merely many different people who respond to the crisis differently?

February 2022 in NYC, on the phone with my parents in Moscow:

I hear fear, nervousness, and a stoicism that scares me. There is shock and tears but also cognitive dissonance. They call it a “special operation” which, they say, is not targeting civilians. They mention the expansion of NATO, America’s geopolitical bullying, aggression in Ukraine toward Russian populations and traditions, and so on. They are justifying. I know that there is a five- to seven-year sentence in Russia for calling it “war” but still I can’t believe my ears. I am asking them about our Ukrainian family in Kiev, whom they don’t believe to be in danger. The emotional escalation in our voices is unavoidable. My guts contract and muscles shorten as the distance between our views grows.

- Nausea gives way to a burning inside: this is a regurgitation of rhetoric as old as the Cold War. In his speeches, Putin is hard as a mirror, refracting the blame onto his interlocutors and dead-ending any debate.

- Sure, it is easy for me to ask from the US: why are there no protests? In Russia, there are real consequences for those few who speak out.

- Are we Russian citizens conformists with low self-esteem, or almost genetically scared? After all, the Gulag was only shut down in 1960.

[ID: Two dancers extend their arms, mouths open. They look down.]

Still image from video by Anna Pronina

The next few days, in my NYC studio:

I’ve always believed that art shouldn’t be propaganda.

Yet there is no place for nuance and ambiguity now, when people are being slaughtered.

I roll on the floor and moan, then scream and growl.

I WORK WITH MY TORSO AS THE STARTING POINT,

I TOUCH FROM MY BELLY.

Nothing that I planned to do for my new work makes sense anymore, though certain things that were cooking foreshadowed current events.

The tone was different before the war:

DANCE IN THE POCKETS OF MOTH-EATEN FUR COATS. DANCE AMIDST GOLD CURTAINS.

DANCE OF UNHINGED WITCHES AND MECHANICAL SOLDIERS.

THE DANCE BETWEEN THE CLOWN DOLLS FORGOTTEN IN YOUR MOTHER’S ATTIC.

DANCE TO $1 RECORDS PLAYED THROUGH THE SPEAKER OF AN OLD RADIO. DANCE THROUGH OLD POEMS.

For the last 15 years, every time I came home to Moscow, I could see the construction of nostalgia everywhere, like a fog obscuring the senses. Posters in the subway glorifying the WWII victory of the Soviet soldier, monuments to a strong imperial past, and the annual muscle-flexing of parades—all sowed seeds for today’s Russians to say, “we can do it again.”

This creeping propaganda has capitalized on our moral victory over Nazism to feed the notion of a special, righteous Russian mission. The role of the savior, overlaid on the vulnerable ego of inflated inferiority that the Soviet body still carries, fits perfectly. Religion, which maintains a strong grip on society, has reinforced this narrative of sacrifice. The Church’s promise to pardon the sins of those who fight is the absurd spiritual compliment to the government’s investment in death: cash bribes for the families of fallen soldiers.

Before February 2022 I said nothing, dismissing Russia’s military bravado as the vestiges of an old-fashioned Cold-War value system, an expression of the pathetic vanity of our political elite. Distracted by the gaudy spectacle of corruption, we downplayed our country’s militarization.

These days, Russian conservatives consider the fall of the Soviet Union to be a tragedy. Gorbachev’s death early in the war was chillingly symbolic, as Putin shut the doors that his predecessor opened.

[ID: In the foreground, Elena’s arms are thrown back behind her head, fingers clawed. Further away, Tarik stands alert, one arm outstretched.]

Still image from video by Anna Pronina

September, in Berlin:

Berlin is full of monuments reminding us of the atrocities of Nazism. Nostalgia for genocidal totalitarianism is not possible in the face of the Holocaust memorial at the center of the city. We Russians, on the other hand, basked in our hero’s glory after WWII, and never collectively denounced Stalin’s crimes and the disaster of the Soviet project. Are reflection and repentance only provoked by defeat? Or is it a state agenda that controls what memory work can be done, as in the case of imprisoned dissident and human rights activist Yury Dmitriev? For the nationalist right, the deep insult of the USSR’s fall has been festering, awaiting an “enemy” for its release. And now, poisoned by nostalgia, conservative Russians cheer orgasmically for this “Russian mission” to defend “traditional values.” A generation that grips dying world-view systems tightly in its fist leads this war. They look back, squealing folkishly.

We dust off the folk steps and the drill takes over with renewed force.

I overheard somewhere: “When the country wants to kill somebody it demands to be called motherland.”

PRESS YOUR SKULL AGAINST A PIECE OF GLASS

AND

FEEL THE SPACE BETWEEN SHRINKING.

- What does it mean to be a Russian artist?

- Is it to belong to the rich culture of dissidents: writers, journalists, and artists who left Russia and worked outside the country for most of their lives?

- Is it to collaborate with the pathetic vanity of the regime on the ground, hoping to change decaying value systems from the inside by performing in state-sponsored venues to access larger audiences, to offer an alternative perspective?

- Is it to maintain a learned indifference to politics, a cultivated helplessness from years of mistrust?

The Soviet social contract was unspoken, viscous disobedience: “We pretended we worked, they pretended they paid us.” These days the resistance manifests in fleeing the country; since the beginning of the war, close to a million people left Russia in a refusal to participate in this crime against humanity.

[ID: Two dancers in motion, arms lifted, leaning into the space in front of them.]

Still image from video by Anna Pronina

March 2022, in the studio (NYC):

I roll on the floor, with the song that my half-Ukrainian father sang to me on our road trips.

That song spills into cries, mourning, squealing, prayer-like attempts to break the spell…

OCEANIC MOURN.

BEING PULLED UNDERWATER, DROWNING.

MADNESS, A GIFT YOU HAVE SUBTRACTED FROM.

I shake for a long time to escape paralysis.

…and I laugh! I laugh loudly because sarcasm was always the coping mechanism of the weak.

- Was the dark irony that I was surrounded by while growing up a form of resistance?

- Or was our political passivity grounded in despising the regime and refusing to engage with it?

- Is this coping mechanism, this reaction to injustice, uniquely Russian?

I still recall with pleasure those long evenings in small Soviet kitchens when we sang, joked, and laughed about the “ruling class.” I now see this dark humor as an expression of a weak, helpless population. But as a close American friend put it, “Pessimism was the default where I grew up—not necessarily due to cynical calculation but rather pragmatic reasoning.”

I have a sensation of full-bodied, visceral nausea that mixes horror, guilt, terror, and disgust.

Putin’s pact was, you can do everything you want—buy, sell, accumulate, create—as long as you don’t interfere in politics. This was convenient for many, including artists. That unspoken agreement removed any checks and balances. Is the war, then, the logical culmination of suppressed dissent? Dostoevsky said, “Soon the execution of your laws will become a crime.”

This kind of regime eats itself from the inside out. It won’t be overturned from below or above; it will self-immolate.

[ID: A performer’s upper back, close to the camera. Text reads: Disappearance is the new black.]

Still image from video by Anna Pronina

In the studio in Berlin:

The voices of Ukrainians and Russians who left their homes behind are everywhere here in Berlin. My collaborator Tarik traveled three days, without so much as a credit card, running away from conscription without knowing what European country would let him in.

UNCERTAINTY ON THE EDGE.

ERASURE OF ALL THAT YOU MEANT TO CREATE.

NO TIME FOR REST

MOVE AWAY FROM FORMING YOURSELF INTO THE TRACEABLE.

[ID: Tarik in the foreground blurs with motion. Elena, further behind, reaches upward, looking out to the horizon.]

Still image from video by Anna Pronina

In the studio we look together through the absurdity and hysteria that we see on Russian TV:

Elena:

Did you see that the names of the artists who speak up against the war are being erased? Their names are disappearing from the credits and theater programs. Some songs are performed anonymously…

Tarik:

Books by writers who are not silent are censored.

Elena:

You told me about a shaman who planned to do a ritual on Red Square, to get rid of Putin. He was arrested immediately.

Tarik:

Those in power are afraid of mystery… imagine a cemetery where all the names are removed from the stones.

Elena:

Between erased/anonymous names and the disappearance of bodies on the run from the persecutions, people are vanishing.

Tarik:

Imagine Moscow—a stone garden with no names.

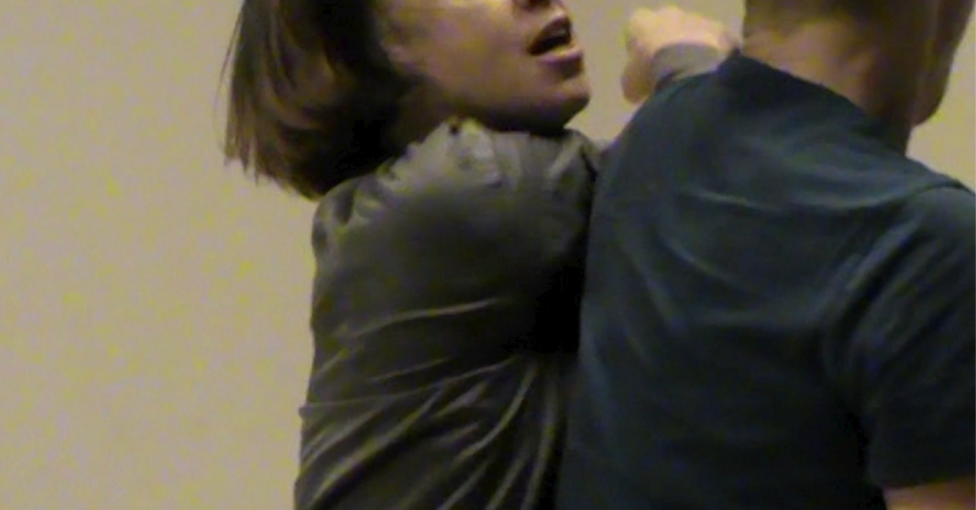

[ID: Two bodies collide at the shoulders. Elena’s mouth is open, mid-breath.]

Still image from video by Anna Pronina

OUR FIRST SHOWING

It was not planned, as nothing can be planned these days. We met in Berlin, its echoes of past war still present. This city remains safe for now, and each day there are more Russian expats.

We have to face our national guilt and collective responsibility.

We have to deal with a rapidly disappearing past, an uncertain future, and no way out. The scale of our uncertainty is something we have never experienced before.

Insisting on being artists, we negotiate the unknown, absurdity, madness, inhibition, and rage, searching for release into another way of moving forward and to find our resistance.

We question whether “we” and “I” still exist.

End.

Elena would like to thank dear friend Louisa Bennion for her sharp eye as copyeditor and proofreader.