Ogemdi Ude: Sydney is a longtime friend and collaborator. We entered into our first major collaboration at Recess Art in Brooklyn. At that residency, we launched our project Living Relics, an exploration of death and grief—how we might externalize that experience of grief and then contend with it in its physical form. I think that Sydney is a brilliant photographer and visual artist. I’ve learned a lot from her over the years, and we continue to exchange knowledge and practices. I also feel like Sydney’s work is very deeply engaged with the body. And we’re always returning to the body, returning to dance movement, all of the variations of it.

So I thought it would be beautiful to speak to you as a visual artist on your entrances into the body at this time, in your practice, in your career, after this first iteration of our project, Living Relics. How are we all continuing to process movement in our respective intimacy, like self-intimacies and interpersonal/intrapersonal intimacies? How does that come through in the work that we make, or the work that we have made? I would love if you could tell me a little bit about your practice and how that led to our most recent collaboration.

Sydney King: I am primarily a visual artist and a photographic artist. With my practice, I have been wrestling with the medium of photography and thinking about what photographs can show. How can I depict the body in ways that maybe are different from how we normally look at images of the body, and what information is assumed from a photograph? How can we complicate our understanding of how bodies are photographed? Lately, I’ve been making plaster molds of my own body and thinking about the reliefs that are made from certain moments in time and certain poses that I’m making, and documenting my body as it is. I’ve been really interested in investigating moldmaking and specifically plaster mold making; I am thinking about reliefs, the concept of the negative, how to visualize negative space, and how a photograph can document negative space.

I was really intrigued by the idea that a photograph could capture a plaster mold that was lit in a certain way such that it looked like a relief, that it looked like a cast. But it also looked like a mold. You’re looking at the photograph, and it’s constantly switching back and forth. It’s a space that is maybe definite in the physical realm, but in the photographic realm, it’s indefinite, and it’s constantly switching. Its spatial reality is in flux.

Through my current work, I’ve been photographing molds of my body in conjunction with their reflections, thinking about how photographs can speak to a different conception of space or conception of the body’s history, how we hold in our body all of these memories and these past experiences that have changed and morphed us throughout our lives. How can we commemorate that in a visual medium, which just shows you what’s there at a certain moment in time? To collapse different timeframes and different moments is something that I’m really interested in.

These ideas came into our current collaboration, where you and I were exploring themes that really resonated with each other, but from different perspectives. We found a way to converge them into a single practice, where a movement practice influences the making of plaster molds and visual material. And the movement then influences how we commemorate or document that resulting material. We continue to document it or work with it in all of its iterations. We work to commemorate these moments that start with individual participants, through working with them, going through the movement meditation, and speaking about their specific grief or their specific loss. That moment resonates throughout our practice in how we interact with each other around our own grief or our experiences in our bodies – that moment ripples out and we continue this iterative process of exploring and re-exploring the weight we hold in our bodies.

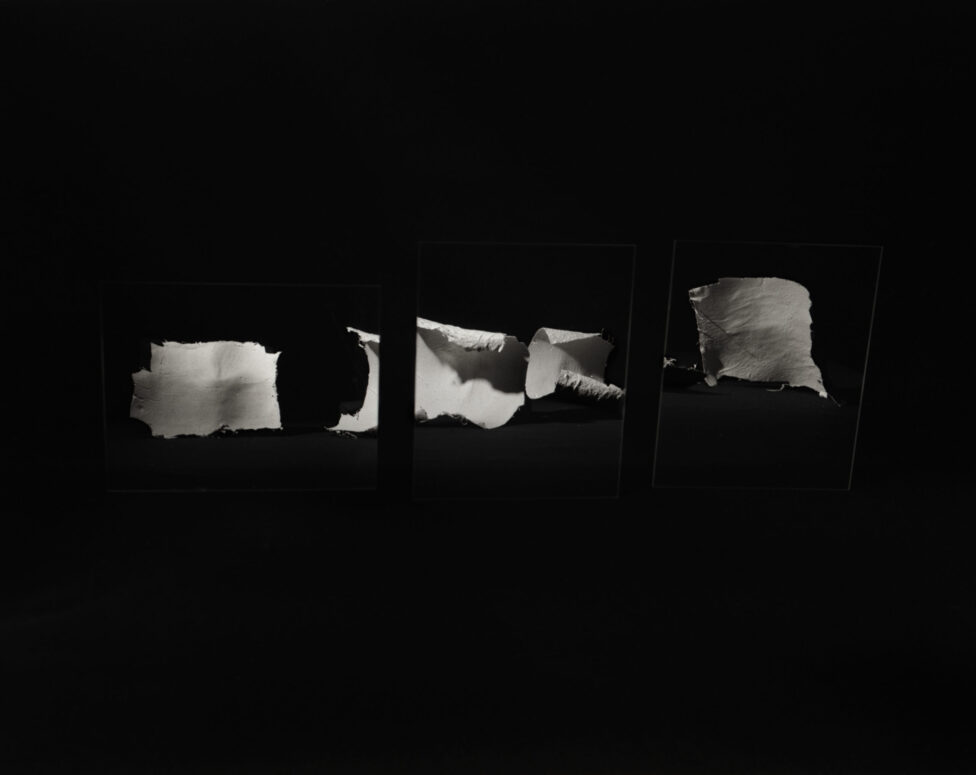

Photo by Sydney King and Ogemdi Ude, Living Relics, installation view

ID: On a wall are two different projections, overlapping slightly. Featured in the projections are two pairs of hands dancing gently with white plaster body molds between them. Below the projections is an altar made from a mirrored shelf, several candles, and plaster body molds.

OU: The term “iterative” continues to come up. When we’re thinking of iterative and iterations, we’re in this redo and remix mode, right? And so, in regards to remixing, what is it like to have this transdisciplinary collaboration? What is it like to step into a performance realm while simultaneously holding on to a visual art vernacular?

SK: When you first asked this question, it felt like our collaboration made complete sense. It was such a—maybe not a logical transition, but an intuitive transition for the work: integrating this performance aspect with the visual arts aspect, integrating movement into a still medium. How can I talk about the fact that this is a moving, living body that’s being encased by plaster?

We think about death masks, which are casts that are made of the recently deceased to commemorate their memory and their likeness. Plaster casts are used in a way that, historically, always calls to the still, or to something that’s in process. Plaster is used to record something that is not moving. It’s used as an educational tool, or as a memory tool, and it’s never the final thing—throughout history, plaster is identified as a material of process.1

Molds of the body and plaster casts are used to keep your body still when you’ve broken an arm, to encase the body in a way that makes it unable to move. I was always interested in plaster and mold-making in relation to poses that maybe weren’t really tenable for long periods of time. I would hold my body in a certain shape for 10 minutes and it would hurt, or it would be really difficult, or I would lose my balance. Through my breathing or through the position, the mold would fall off. It would never really be able to stay on because the living body is constantly moving and changing. So there’s this kind of acknowledgement of movement within the still plaster forms, or the movement evoked through the reflections in the photographs. In the reflections, it’s almost as if the plaster forms are vibrating or that they’re not completely there—there is this tension of what is still and able to sit before the camera, and what is in motion.

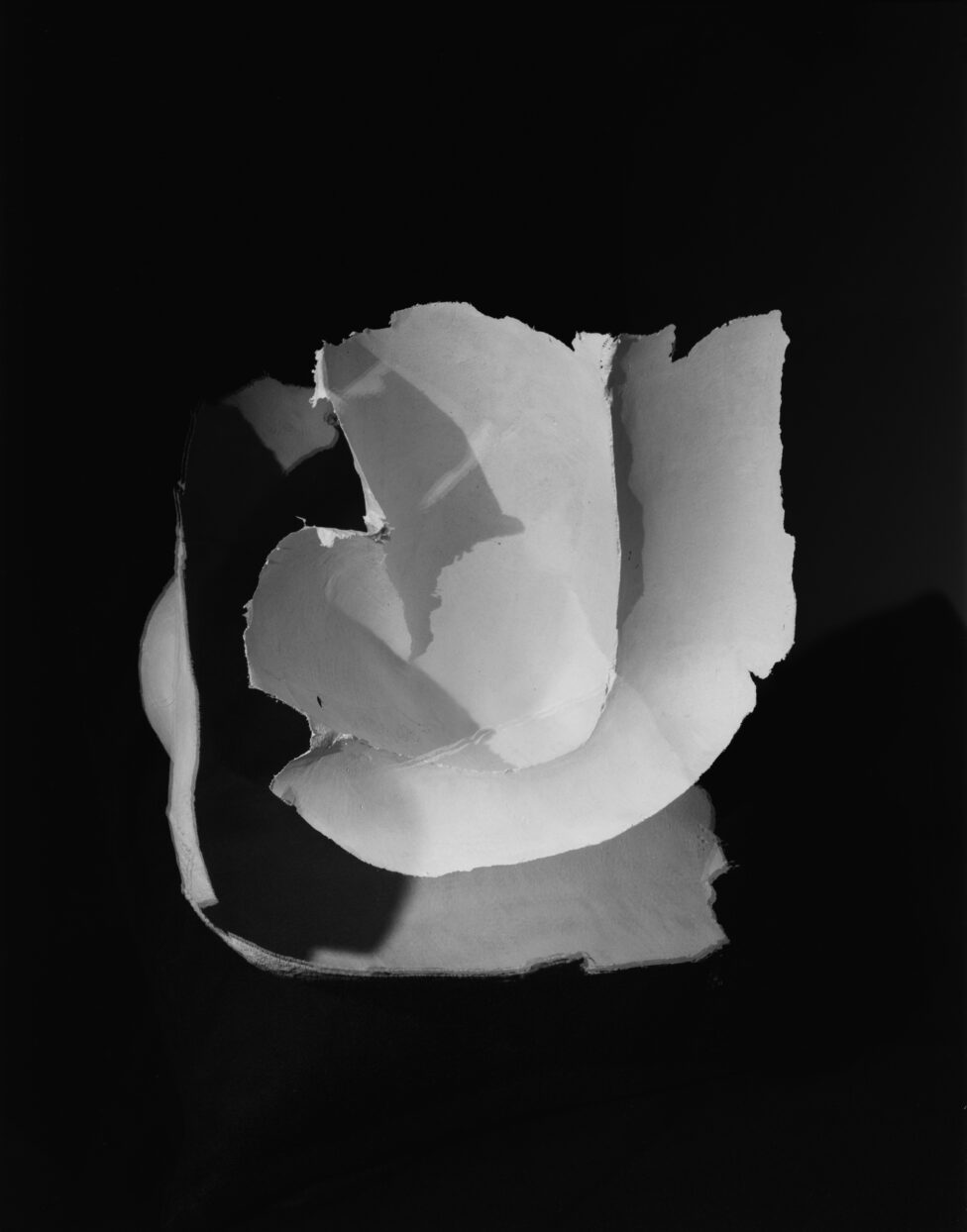

Photo by Sydney King, Entanglement IV (2020), silver gelatin print

ID: A white plaster mold is layered with another mold’s reflection. The forms overlap like flower petals against a black backdrop.

OU: What is a death mask?

SK: Death masks were made through the Middle Ages up until the 1800s and the invention of photography. They’re made out of plaster, and are created to commemorate those who have recently deceased, in the form of a sculpture or bust for their loved ones. To me it feels like a form of proto-photography. Where photography didn’t exist, it was a way to create a somewhat objective impression of the body. These were made right after someone had died and before they went on to the burial process. Usually two plaster technicians would come in, pour and encase the head in plaster. It’s a very scary process. I mean, it’s a process that can only be done when you’re dead.

OU: Do photographs encase the subject like plaster does? We keep on returning to this language of the plaster encasing and holding. And do you want it to?

SK: Maybe the photograph does kind of encase the subject in a sense that it’s documenting the subject’s features or expression in a very particular moment in time, either when the plaster hardened or when the silver halides reacted. It’s just a single moment, and yet how that moment lasts, in the case of death masks, is kind of this forever stretch, recording what a person looked like (although death masks usually don’t really look like the people that they’re made from, because their features are transformed by the transition from life into death).

A death mask exists as a single recording that’s not really an accurate record of who someone was. And I think that a lot about photographs as well. There’s so much that we think we know from photographs, or we assume we know just because they’re so good at describing what the body looks like, or the textures of things.

Every photograph contains its own world. Photographs are little universes of in-betweens, of moments that we may not necessarily notice or see with the naked eye. Maybe they will have never existed in our consciousness, but they’ve documented all the same, and are thus incorporated into our memories.

And so how can we continue to interpret and to see into the photograph–into the image that was made of a moment that we may not necessarily remember, but that continues to live a life of its own? Do you think that the photograph kind of embalms the body?

OU: I don’t think I ever want a body to be embalmed. I don’t know if you’ve seen an embalmed body in real life. It’s so frustrating. Me and my friend, Fariha, have been talking about this a lot. About how, when our friend passed away, it just didn’t look like him. And similar to the death mask in some way, it’s almost a record of him. But not really; it’s a record for the purpose of us being able to be present with that body in its transition. The death mask is a way of preserving a person who doesn’t need it—the dead doesn’t need a death mask. The death mask is the record for those who are living, right? So much fanfare around death is for those who are living. And the embalming process is for preservation of the corpse so that it’s no longer just organic matter, but able to be shared with the people who want to say goodbye. I think about that scene from My Girl where that little girl was crying, like “where are his glasses, he needs his glasses.” But this little boy died. She saw him in the casket and he didn’t have his glasses on, so she was like, What the hell is this? Where are his glasses?

When I was younger, I used to get so upset when asking my mom about death. She would explain what she knew of as heaven. I would be like, when I go to heaven, do I have to be in my old person body if I die when I’m old? Or do I get to be back to my cute young person body? And she was like, well, you go as you go. And I was like, “but I don’t want to go when I’m old,” cuz you know, when you’re younger, you think being old is the grossest thing on earth. I didn’t want to die young, but I didn’t want to live forever—”old” [laughter].

I’m super intrigued by what you’re saying about capturing something, but are we really? I know I don’t want the photographs to embalm. The photograph is more so like… Photographs haunt. They are these haunting objects that we want and that we’re so desperate for. But if we expect them to embalm something, then, I don’t know… We want more from a photograph than it can give us. And I think a part of that is, yes, we do want a photograph to embalm something. But if we think about what embalming does, it’s never giving us exactly what we want. But we still want it to happen.

SK: I’ve never seen a deceased relative, as in, their actual body. It’s weird. For me, the funeral has been with just some ashes—passing them around or scattering them in the water.

OU: Perhaps, we do need that. Because when someone closes the casket, it’s another death. You don’t realize that until the casket is closed. And then it’s another death when the person is buried. There are all these iterations, as we return to that word, of death that continue… A question I have for you: when you hear the terms “body,” “embodiment”, and “movement,” how do they resonate with what you do now?

SK: I’m really interested in how the body sees. I remember this one dance class where we were focusing on a certain part of the body. You told us to imagine that there are eyes on that part of the body, and that we should look around the room with it. Say it’s my elbow. My elbow is looking at the ground, and it wants to look at the door, and now it wants to look out the window. I’m being hyper aware of a certain part of my body and what my perspective of the world is from that part. Which is something that I think about a lot, this embodied seeing.

I have this desire to have the camera body mirror the body that it is photographing. Or to have the surface of the negative, or photosensitive material, mirror the curvature of the world around it. To think about the intimate relationship between the subject being photographed and the photographing device, itself. Because the body is so often depicted as one thing, or in a certain way, and I’m always interested in how else I can visualize it.

What if you could only take photographs using the object you are photographing (so, to photograph pumpkins, I would need to hollow out a pumpkin and create a camera from it)? What do our elbows see? How does this perspective shift the kinds of images that can be created? I’m also thinking of photography as an impact point for movement.

OU: Impact point, can you explain that a bit?

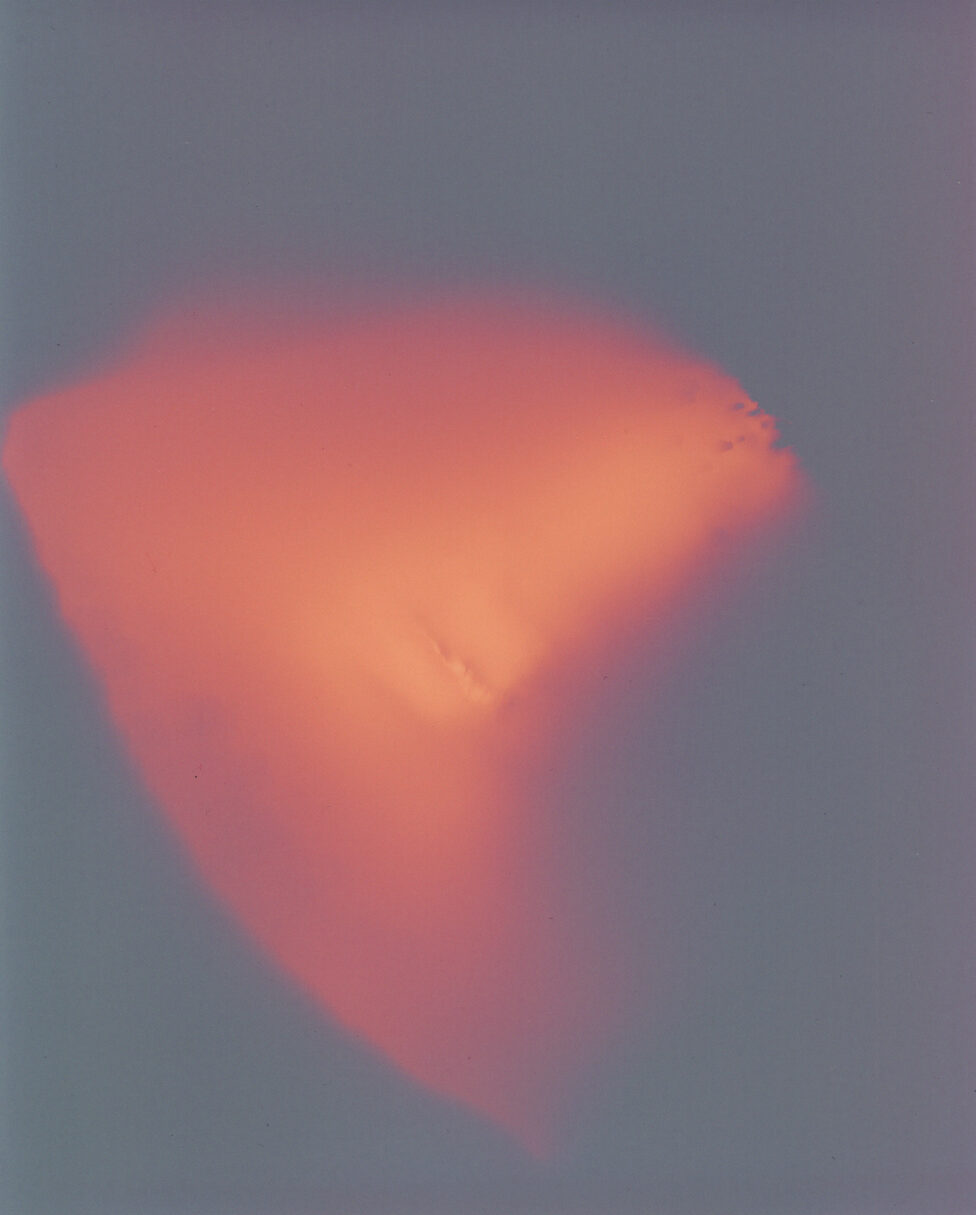

SK: I’m thinking about the lumens, specifically. About the overlap between those prints and the movement practice. In the movement meditations, you would ask us to focus on the relationship between our bodies and an external surface. We would visualize the shape of the impression our bodies made on the floor–the impact points of our bodies, what those looked like, and how they shifted with each breath. We would make impressions of those impact points by molding them in plaster. And then those plaster molds would be placed on top of photosensitive paper; the photograph is making contact with an object that has touched the body. It’s a relic, showing an indication of impact or of presence.

Photo Sydney King, empty&heavy (2021), lumen print.

ID: A blurred, red/orange impression of a plaster mold exposed onto Ilford Fiber Paper.

Maybe we’re always trying to capture movement or an element of the moving body with photographs, which is kind of an impossible task. So we just get these impact points where we have some indication of weight, of where we were, or of a spatial relationship. And that’s all we can really get.

I’m thinking about the nature of watching performance, the durational aspect of it. And the way that I can sit there and feel like my whole self is being engaged in watching something or participating in something, with my brain or through mirroring movements in my own body. Then it’s gone, but it exists in my memory. I want photographs to open up that same space where it’s not just a documentation of something that happened, but something that exists in my memory that’s constantly changing, that exists in my body the way that a performance can.

OU: Those are brilliant thoughts.

SK: Noooooo.

OU: Sydney, I must say, what you just described was kinesthetic empathy. That feeling of witnessing something move, or being moved by something moving. It can be anything, like the trembling when you’re watching someone else dance, and you really want to get up and dance. Resonance of watching, like a cuckoo clock, ticking back and forth or some shit. And then feeling some sort of wave in your body. Like the wind on your neck that’s moving you slightly, which is not limited to what can be seen with the “ability of eyesight.”

SK: Yeah. You put it really well: the mirroring, the empathy, or the desire to move with whatever movement I’m witnessing. I want that for photography. And I don’t know how that can happen. I’ve been thinking about creating this empathetic relationship between the thing that’s photographed and the surface of the photograph, or creating a different kind of photographic space that allows for multiple realities to coexist on one plane. Maybe it’s just something that you can sense but not see, where the challenge is always like, how do I make it seeable? How do I bring it into a different kind of existence, these things that I know are there but can’t quite explain or substantiate? How do I drag it into the visual realm?

Our collaboration made me think so much harder about photography, about care, and about the relationship between us and any person who wants to work with us. It’s a big thing to be handed memories and to care for them. And I’ve just been thinking a lot about the role of the photograph in that care and how to extend that care through being really clear about how someone is photographed, or photographing someone in a way that shows that I care, that I’m holding their memory.

OU: Makes a lot of sense. Thank you so much Syd.

SK: Thank you.

1. Plaster in Edouard Dantan’s Atelier Paintings by Emily V. Madrigal

Cover Image Description:

The reflections of four white plaster molds are aligned next to one another against a black background. They are dramatically lit, creating shadows across the curves and accentuating the texture of the molds.