DANCE ADVOCATES IN BELGRADE: A GPS/Global Practice Sharing Meeting

November, 2017

I travel to Belgrade, Serbia with Movement Research’s GPS/Global Practice Sharing program with New York artists Peter Sciscioli, luciana achugar and administrators Marýa Wethers, Barbara Bryan, and Lydia Bell. We’re invited to meet with cultural workers and artists about the political, financial and social conditions of the Serbian Contemporary Dance scene over two days of meetings. The conversation promises to be enriching and empowering because as New Yorkers, the opportunity is rare to sit, listen and talk about the variant conditions of dance and the arts; in this case, we focus on the Balkan circumstance. The group immediately forges professional and institutional alliances with our national and European counterparts, there is a consensus to resource share. The importance of community is in focus here, the meeting helps us find our riches despite our deficits and we find power in our struggle; I’m energized and return to New York revitalized by these cultural advocates.

The following is my summary of the days we spent together from an American and New York-based perspective. In my career, I’ve had limited access to artistic opportunities in Europe but the Balkan region is one I’ve had the fortune to have visited twice. My affinity to the Balkan region started a year ago when I was invited to perform in two Contemporary Dance festivals; Kodenz Festival in Belgrade, Serbia and Performativ(a) in Skopje, Macedonia. Since then, the Balkans have become an extension of my dance network, a location that’s inspired my work and world view.

The Contemporary Dance community Belgrade has proposed these meetings with the hopes that the Ministry of Culture grant the Contemporary Dance field a place in their national dance budget proposal. The small budget that the Ministry has given to the field of Contemporary Dance and its cultural workers in recent years, has been pulled from the budget and the meetings are to:

1) Bring visibility to the Contemporary scene in Belgrade.

2) Hope that someone from the Ministry of Culture will attend one or more meetings.

The collective subtext is to make room for dance, the problems are beyond economic here, they run deep with a history of governmental corruption and the devaluation of the arts⎼ specifically experimental and research-based Contemporary Dance⎼ the value system that culture falls into has repeatedly denied the worth of movement-based forms.

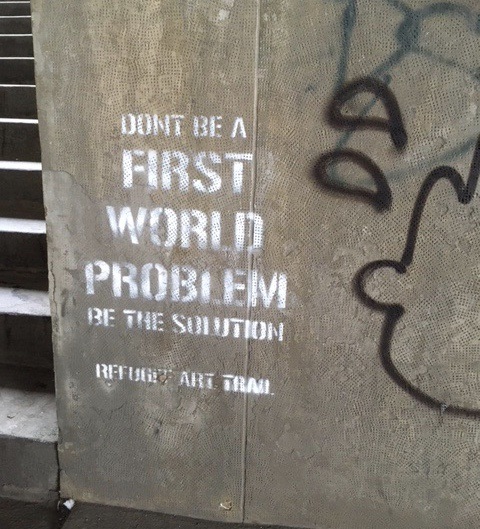

Wall art across the street from Magačin from the 1992 Olympics. Photo courtesy of luciana achugar

Day 1: We gather in the Magačin courtyard where the Berlin-based Karkatag Collective artists Gisela Mueller and Dejan Srhoj guide us through prompts that activate different “stations.” A conveyor belt with croissants taped onto it is activated by the pedaling of participants. Prompts are printed onto receipt-like papers that come out of three small dispensers; we press their buttons and do what they say: “carry boxes from one corner to the other,” “move a table and rearrange its objects,” “stand in the center while moving your feet in up and down motions.” I find myself dwelling in the surreality of the space, where we easefully socialize and absent-mindedly participate in both a social and mechanical time together.

Willy Prager and Stephan Shtereff, affiliates of the Nomad Dance Academy Bulgaria, guide us into the Magačin performance space; a room with cement walls, modular risers and a stone floor; this is the site where most of our meetings will take place. There’s an installation of a row of light bulbs⎼ they’re high up on the wall and mounted onto wood⎼ each bulb is assigned a European country. Represented are Eastern and Western Europe, Scandinavia and Russia. Prager and Streff begin a choreographic game, a physical survey where guests from the represented countries are asked to answer (through spatial activation) questions that define them as artists or cultural workers. They start with: “Please place yourself on this ‘map’ according to your country of origin” (they find a geographical standing space on the floor). “Now please move through all the countries within which you practice your art” (two thirds move fluidly throughout the “continent” of Europe). “Now please raise your hand if you earn a living wage” (there is nervous laughter, only a few from the Balkan or Eastern European region raise their hand) to this question, the rest of the “map” raises their hand. It’s here that I recognize that the United States contingent of the room is the only group that isn’t playing, as we watch, the “living wage” question causes a reaction in us too.

To the partners from the United States, this question is so familiar, it’s not so much a tense or nervous identity anymore but one based in reality, I wonder if we’ve always felt so disenfranchised, if defeat is part of what we’ve signed up for as artists, specifically body-based artists. At once it’s clear that disparity, scarcity and need lies within the Eastern European contingent of the group and in a parallel way, for the artists from the United States too. The Eastern European participants’ trajectories in the choreographic game are also the most mobile, they’re a nomadic group in the “map” of this exercise that generally works outside of their birth-countries and geographical regions; a symptom of the lack of funding in their home countries. To the living wage question, only a few raise their hand. My inner light bulb lights up to this kindred disparity and I begin to play my own United States version of the game: “How many people work one or more jobs to support themselves?” 100% of my peers would raise their hands at that question.

Our hosts in Belgrade are Station Service for Contemporary Dance, an organization that’s run out of Magačin, a performance and gallery space. The events are also in partnership with Nomad Dance Academy (members of Slovenia, Bulgaria and Macedonia); Brain Store Project Bulgaria; Lokomitiva Center for new initiatives in arts and culture Macedonia and Tala Dance Center Croatia. Essential to the group of attendees, is the presence and perseverance of the Nomad Dance Academy, a network of artists from the Balkan region who have bound together as advocates for Contemporary Dance since 2005. These partners are visionary pioneers of the Balkan Contemporary “scene.” Marijana Cvetković along with members of her organization comprised of artists, interns, and cultural workers are our gracious hosts at Station, Belgrade. To herd us in a group between each event, meeting and meal, we’re given meal tickets that can be used during our meal breaks within the gallery space that’s adjacent to Magačin and it’s clear that our conversation⎼ even during meal times⎼ will encompass resource sharing and idea building within the arts in political, personal or abstract ways. Talking, eating and listening fills our days.

Dance advocates at dinner, photo courtesy of Barbara Bryan

I’m moved by the amount of time that language is given here⎼ an element that’s as important as the art itself ⎼ and it’s beautiful to be in the company of others who think the same. The term “Contemporary Dance” in the Balkans stands as the definition of what New York artists now call, experimental dance or perhaps to some extent, do it yourself (DIY) dance. Historically, experimental dance has endured as a marginalized art form because it’s an economically un-capitalist practice that’s based on the labor and energy of the body unlike any other form. I must interject here to examine that I’m only speaking to the marginalization of experimental dance forms in this report and that I deeply recognize that traditional, indigenous and vernacular dance forms suffer even greater disparities because of oppressive White oppression, control and legitimization. In all forms of dance the body is our medium, brain and life; the body holds memory and is the best archive of our work. From an audience’s standpoint, their bodies sit or stand in space to experience a performance; hence dance cannot exist without the commodification or utility of any body and therefore, the body also needs space. Dance can not be preserved, recorded or bought as an authentic object of itself because dance is free of being a product and for these and other valuable reasons, dance is a threat to people who chose to confine it to any economy.

Politically, there is risk that needs to be taken in order to give dance forms the proper place within an economic value system. It’s a risk that must be taken within the realms of research-based and experimental forms (as well as traditional, indigenous and vernacular dance forms); a risk that upholds the potential of outcome and exchange⎼ not the monetary value of product. Policy and risk go hand in hand in this topic, especially in Serbia where the government has chosen to devalue the contribution dance can give to cultural identity, enrichment and the healthy, balanced development of a society. “Make room for dance!” they say.

The first day of meetings begins with a conversation between Serbian professor Milena Dragićević Šešić and Biljana Tanurovska Kjulavkovski, representative of the Nomad Dance Academy Macedonia. The topic: How to use the existing cultural policy framework to make meaningful change? The conversation points to the policy makers and to the difference between the creative industry of commercial or mainstream art versus experimental, subversive and research-based art. Suggestions are made about the need for more interrelation between large institutions, where perhaps a museum (for example the reopened Museum of Contemporary Art Belgrade) could share resources and adhere an entry through the popular scene to the smaller experimental movement-based communities. Resources and how they’re managed civically are central here and there is also the awareness around a new imagination of culture that’s fostered by the government to serve the people. Their conversation is a continuation of the earlier light bulb game and it drives us into the reality of policy and how it should work for the people. In the Balkans, the current cultural policies are threatening with the underpinnings of censorship and this aggression withholds artistic potential rather than promote the development, empowerment and growth of Serbian society.

The Balkan situation is complicated because of their Ministries. These countries hold post-socialist governments that swing to the left and in most cases to the extreme right of democracy. There’s still the old Socialist school of thought that believes that the government should stand behind everything that a society needs. That a government should tend to its people for basic needs and rights, yes it should; but with a divided post Yugoslav Wars identity, it’s beyond anyone’s grasp to truly find unity again. These political variants of conservatism add to the conflicts in the region that trickles down from the politicians and into the lives of their people.

In the United States, we believe in the possibility to re-invent and innovate; we believe in the individual. Inherently, we battle collectivity, community or the necessity to meet every citizen’s basic need because we’re built on the mentality that: If you can dream it you can do it (no matter who goes down with you or has to suffer along the way). The individualistic viewpoint is harmful in the U.S. to say the least, it functions on the inequality of wage and the labor of the poor that produces a society without the continuity of enrichment or cultural heritage. In our country, people’s potentials are truncated and the lack of equity and equality runs the entire structure raw to the bone. The healthcare, education, and prison systems are some battlefields to name a few. In this capitalist tradition, we fail to honor the arts as a national treasure. In the U.S., where the arts are worthy of financing if they produce commercial success (at best), we as artists and cultural workers, survive inside of a system that makes us seek out alternatives in crowd-funding, philanthropy, privatisation and elitism of the arts. To this dilemma our European partners cringe, “No! What does this mean? How do you make art and work jobs too?!” We just do, and the difference is that we accept (with accustomed defeat) that this is the way our country has worked and it’s hard to break the mold of capitalist forces. We find ways to barter, hustle, to make monetary means out of short-term or steady jobs and that’s how capitalism works and that’s how we’re victims and at fault within our system, we conform. It’s not right but it’s been normalized, in the European mind-set whether Western or Eastern, our capitalism is a monster and we agree. They fear that their countries are bound for a similar future as more conservative heads of state take offices.

During one of the panels, people in the room made deep regretful grunts when we told them that we don’t have a Ministry of Culture in the U.S.. Compared to the condition of the arts in the U.S., the well funded Western European partners paint cultural budgets that sound like a dream. To the Balkans, the dream starts from a more basic place; in giving experimental thought a place of dignified recognition within their national heritage.

The concept of intangible heritage comes up when the subject of national heritage was introduced. Whereas Folk dance forms preserve a nation’s identity, especially in Eastern Europe where these thrive within the national budget, experimental forms of any kind have intangible heritage, hence experimental dance forms receive little to no funding. A panel called Imagining new dance spaces, lead by Dragana Alfirević, Marko Milić, Milan Marković and Iva Nerina Sibila surmised imaginary spaces that they can only dream of given the current policy in Serbia. The imagined space would be home to a research-based community of experimental dance makers. Among the imagined spaces and potential outcomes were: warm floors, rooms for thinking and talking, porous spaces where people from different communities feel welcome to join and educational programs for adults, youth and children. The conversation travels to the education system where the hope for societal shifts have potential. The shifts can thrive if we teach the value of experimental forms to children and with a view of art that upholds experimental dance forms as a sound component of human and societal development.

Later that afternoon, representatives of Balkan dance spaces, non-governmental organizations and institutions presented their work (one presenter was from Berlin). In this section entitled, Reality check on dance spaces, we are generously given a survey of the region’s struggle (except for in the case of Berlin) to survive within their government’s bureaucratic and political obstacles as they pertain to the Contemporary Dance scene. Contributions are made from Ljubljana, Sofia, Zagreb, Skopje, Bucharest, Belgrade and Novi Sad. From this we learn about successes and losses with their histories that exemplify struggle, wit and innovation at its best. Vava Stefanescu from the National Center for Dance Bucharest, Romania gives a recent success story where they’re granted 13 million Euro to begin renovations on their dance building in the coming year; to this news, we cheer.

Photo courtesy of luciana achugar

Day 2: We begin with a debate in the format that’s modeled after the British Parliament in a game entitled, Temporary parliament for dance. The first topic discussed is the lack of space for dance in Serbia. One position is that Serbian cultural workers missed their chance to have a dance community and center in 1994, when funds were allocated to their closed and economically struggling country. The statement poses that the lack of cohesion from within the community has made it difficult to propose a concrete union for the Cultural Plan, which is still currently exhibiting its effects. This position functions on the ideology of the conservative pyramid system, where resources trickle down to the people rather than circulate with transparency.

The second position was one of allocating space for dance for the bourgeoning experimental communities in both Belgrade and Novi Sad. This stance on the current dance situation claims that the community lacks an autonomous model that fosters creative freedom of expression in programming, artistic practices, and in collaboration. This position suggests that there should be levels of public funds that serve the public openly by networking and allocating resources in tiers or decentralized methods. The need here centers around “mak[ing] the government see that they need dance rather than the mentality that dance needs them in order to exist.” In this game of choosing sides, the Parliament format eventually brakes, people lose interest and a conversation circus begins. The game proves that the format of Parliament is not viable for this community, let alone any progressive model of governance that wishes to give power to the people. The game’s divisive system proves that a binary governance doesn’t serve for public discussion of collective ideologies. Rather, it makes for narrowed ideas and stunted growth where “ground-up” structures battle “pyramid” structures; perhaps Serbian cultural workers should seize the day and activate outside of either structure, maybe there’s a chance there to reinvent how art can be governed.

Magdalena Ritter from Germany speaks about Tanzplan Deutschland, a fund that she spearheads to allocate resources to nine different educational organizations. The statement in the cultural plan for this fund to reach its fullest economic potential is “Dance is an important contribution to society and the state should engage with dance.” With this national ideology around dance and its contribution to society, Ritter is able to help institutions support the importance of dance in society. The program gives the dance educational system longevity, cultural enrichment and cultural inheritance for future generations. From this presentation we learn that dance as an “intangible” art form, can have value within a nation’s heritage. Her takeaway and advice to the Serbian artists and cultural workers is that “You need a good enemy to become a stronger group.”

Strategy, resource, self-governance and art are some inspirational words during the Serbian Policy meetings. I’ve left thinking of ways that I could work with and around capitalist structures in the U.S. to benefit the arts with innovation and integrity. I think about how lucky we are to at least have an economy of jobs and employment and suddenly I’m grateful for the chance to hustle. There are many flaws in our system, but at least there is a culture of employment and we can chose to work for what we need. For our Eastern European counterparts, their economies aren’t thriving so job markets hinder the potential for most basic needs, let alone an artist’s lifestyle. I doubt that picking up a bartending gig in Serbia to help support an art career is very easy to come by. I also doubt that the stigma around this type of labor to make ends meet is looked upon without judgement or class politics. To make my work possible, I chose to work seven days a week and I’m able to make work with freedom of speech and expression. I wouldn’t trade my hustle with subsidies from the Ministries of Culture that don’t believe in the freedom of experimentalism, research-based work or innovation. I hope that this freedom won’t change too quickly with the current administration and if it does, we can look to our Eastern European counterparts for ways to survive a nationalist, conservative, and oppressive censorship agendas. In Ritter’s words, “You need a good enemy to become a stronger group.” I return to my apartment in Brooklyn, New York with the will and energy to look beyond the communities I align with, to find wealth in some version of freedom that might be available to me and to find ways to sustain my relationship to the Balkan and Eastern European region; a place that’s willing to fight for dance; the struggle is well worth it.

GPS closing meeting, photo courtesy of Barbara Bryan