Glenn Potter-Takata: I was kind of interested in talking about emptiness.

Mina Nishimura: Yeah.

GPT: I know you’re working on something called EMPTY SCORE.

MN: Yes. Oh, yes. Yeah. Thank you for doing that. [Glenn performed Mina’s EMPTY SCORE (for an empty body) as part of 888, a performance marathon to benefit Red Canary Song at Center for Performance Research on June 18, 2022.]

GPT: Yeah. I mean, are you interested in talking about it? I know for myself, in a Buddhist context, I have sort of my own ideas on what emptiness is or could be.

MN: Right.

GPT: I’m just curious… When you say empty score for an empty body, in this sort of performance context, what do you mean by emptiness? Or like, how are you thinking about it?

MN: Yeah and emptiness is also very much connected to “no mind.” I think it’s a really unique concept. Because it reflects Japanese philosophy in a significant way. For me, emptiness is or… like, no mind is more like a space or a zone. Like a space for any possibilities to happen, to come. It’s more like a space where anything can arrive. So it’s not so much about emptiness as an opposition to fullness. It’s not about “there is” or “there isn’t.” But it is just a space.

GPT: Earlier this morning I was actually looking at Hannya Shingyo, the Heart Sutra, which–you could say is the main sutra in Shingon Buddhism, and the whole thing is about emptiness or kuu (空).

MN: Yeah, kuu. Yeah.

GPT: Yeah. Hannya Shingyo talks about how emptiness has no form, but it is form. I don’t quite exactly know what that means, but I’ve been thinking about it a lot. There’s also the main sort of mantra in Shingon, which is the mantra of Mahavairocana Buddha (or Dainichi Nyorai in Japanese, the Great Sun Buddha). It goes, ‘On bazara dato ban’, which we speak in Sanskrit as opposed to Japanese. It roughly translates to “the world [or universe] is a diamond.”

MN: Mmm. Wow.

GPT: For me, these two things [On bazara dato ban and kuu] kind of co-exist. They’re related as a juxtaposition. While the universe itself and the rules of that universe are unbreakable–because, you know, a Diamond is Unbreakable– all of the actual things in that universe are hollow, or empty of form. They aren’t in a fixed state.

MN: Right.

GPT: And so in that sense, while the universe and the rules of the universe are fixed, all of the things in the universe are temporary, or constantly in transition.

MN: Yeah, I agree. That’s the thing… it’s a little difficult to visualize because also, for me, emptiness is not a fixed state. It’s not just like an empty… box. But it is a fluid state which constantly renews itself.

GPT: Even the emptiness itself isn’t permanent. Yeah.

MN: It’s really tricky when you think about it. It’s really confusing. But yeah, because ultimately we associate emptiness with a very still, like still modality, but emptiness is more like a fluid modality… The modality of energy is different because when there is a motion, when there is something, I feel energy has a direction, energy is more like an arrow. So it’s visible that there is a thing, and the thing is being pulled toward a specific direction, more or less. But I think in emptiness, energy takes the form of particles. So, it doesn’t take any specific form. But at the same time, it’s not a dead zone. There is energy, some sort of energy, but a specific form just doesn’t get established. It looks empty. But actually, it is a flowing pool of potential energies. That’s my image. Yeah, I’ve never seen, of course, an emptiness. But that’s how I want to visualize emptiness.

GPT: So, how would you integrate something like this? I guess, in a very practical sense, how does the concept bridge into performance?

MN: I think there are so many layers, for example, I tend to incorporate a lot of silence. A lot of times nothing is happening in the space, or, at least, nothing is happening in the main space where it is visible to people. Sometimes things are happening in the back area or peripheral spaces. But the main area is kind of empty and like a silence. That’s one strategy. But also I work with this specific kind of energy, energy anatomy. My body does not reach anywhere. Try not to establish anything. Try not to become something. Before reaching somewhere or before establishing anything…I would redirect my energy. Or I would abandon what was about to emerge or happen. So nothing gets established in space. And I feel that is very much connected to my interest in emptiness as a space of potentiality.

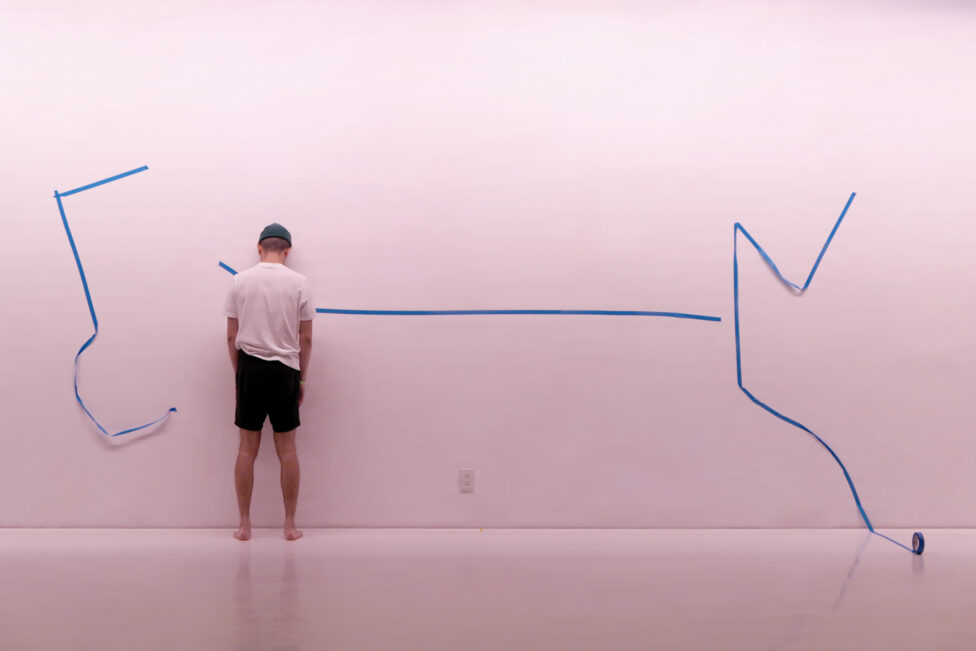

Photo by: Jesi Cook

[ID: Glenn, in rehearsal clothes and a green beanie, has blue tape across his face in multiple places.]

GPT: It’s more of a compositional emptiness.

MN: Yeah compositional emptiness but also as a movement practice… instead of reaching somewhere, maybe you can always move in an ambiguous form. Or like a very soft form which constantly keeps transforming. I’m also trying to create a practice that leads a body to fluid emptiness, emptiness that constantly renews self. Like empty self, but also renew self. [breath]. Yeah.

GPT: In the text of the score for Empty Score you talk about a shadow too. I’m curious about this because a shadow too is like a form without a body.

MN: Right.

GPT: It’s kind of a metaphor. A form without form, or a form with formlessness.

MN: That’s true. I’ve been really interested in this subjectless body. I still cannot find a good language to describe what it is for me… A subjectless body is like, instead of, I do something, or I make something, I’m “being moved” by something all the time. Or always, I’m in between passive and active mode. It’s not like I determine or I make that action, but rather the potentiality of the action is already within me. So existing potentiality is the one that moves my body. It’s a very tricky state, but, to me, that’s how a subjectless body exists. And I feel like it creates a very specific performance modality, too.

GPT: Yeah, it’s the part of yourself that can’t be named.

MN: Yeah! You can put it that way, too. You are moving, but you’re like you don’t know what’s happening!

GPT: You’re not quite sure where it’s coming from? Yeah.

MN: Yeah! I’m very much interested in that kind of physical modality.

GPT: It’s, like, funny to talk about these sorts of Japanese things in such concrete terms. Because Japanese can be so vague sometimes.

MN: Yeah, totally.

GPT: You know, I study at the Shingon temple in LA. The High Priest talks a lot about how he addresses us American students very differently than he would students in Japan. Like the American students need or desire a greater amount of specificity.

MN: And they need to know the intention, the goal, like where we are working toward.

GPT: Yeah!

MN: Different mindset.

GPT: Yes.

MN: Very interesting.

GPT: Or like, in Japanese a lot of the time you can’t even distinguish between what’s singular or plural in conversation. The exact same word is used for both, and you can’t always tell what someone is referring to. Sometimes I’ll be talking to someone, and suddenly I won’t quite be sure about what’s going on anymore. Like, ‘Wait. What are we talking about?’

MN: That’s so true. And we also tend not to use a subject… Like 私 [Watashi or I] or あなた [Anata or you]. So sometimes you don’t know who is doing the action or who is the subject? And even some books are written like that. I think it’s really hard to translate some Japanese novels because you can’t tell who is making the action. And we like that kind of vagueness. We see that vagueness as a mystery-space for potentiality and find it poetic.

GPT: And then a translator would have to name something that wasn’t named in the first place.

MN: I guess the translator has to use their poetic sense and decide. It’s a different culture. I think the Japanese language is also designed to deliver more nuances than meanings. So it’s not useful for clear, precise communication. You always… You have to keep guessing. You have to keep sensing each other. And yeah, sometimes it’s okay if we’re not talking about the same thing, but we can just sort of like talk around a thing, you know?

GPT: Sort of move together.

MN: Yeah, exactly. I think the Japanese language is like that. That’s why a lot of Japanese people have a hard time learning English. Kinda very opposite mindset. I feel like I have to change my personality when speaking English.

GPT: Oh, yeah. I could see that.

MN: When I speak Japanese I can be a little more like, I don’t know, passive and softer? In English I have to be more direct and determined.

GPT: Right. Right.

MN: And it’s not only about the design of the language. It is connected to how we see the world, how we process the world.

GPT: Yeah, I was thinking, related to emptiness that the character used for this kind of emptiness, kuu [空], is the same one used for sora [空], for sky.

MN: Hmm.

GPT: I always thought that was interesting. Because a lot of the time, at least in an American context, or maybe a Western context, when you say emptiness, I think more of a vacuum? Or something like that? You know? Closer to a concept of absolutely nothing in a more physics sense.

MN: Yeah, I agree. Because I think emptiness here is very much connected to whether there is or there isn’t. It implies like there was something before emptiness. And you took the thing out so the physical space became empty. So there seems to be this solid state of emptiness. But as you mentioned about kuu (sora or sky), I see it more as a space. Emptiness is more like an open space where anything can flow in and anything can happen. Anything can arrive, I think, in this emptiness. But you just don’t want to get fixated to one specific thing or modality. You have to kind of keep just flowing and let it go. Let it go. So nothing takes a specific form. Yeah. But it’s a hard concept to really understand. It’s a little like a mystery. There is a mystery around emptiness. Yeah.

And as you said, I don’t think emptiness is just like a void, like, just dead space. It’s not like that. I think it’s similar to the concept of no mind. No mind doesn’t mean like we don’t think anything or we don’t feel anything. It’s not that kind of no mind-ness. But it is more like a fluid state. Fluid modality. Yeah, it’s like, when you do meditations, anything can come to your mind, but you just don’t stick to one thing. Just like, let it go. Let it go. Let it go. Then it constantly renews itself. Yeah.

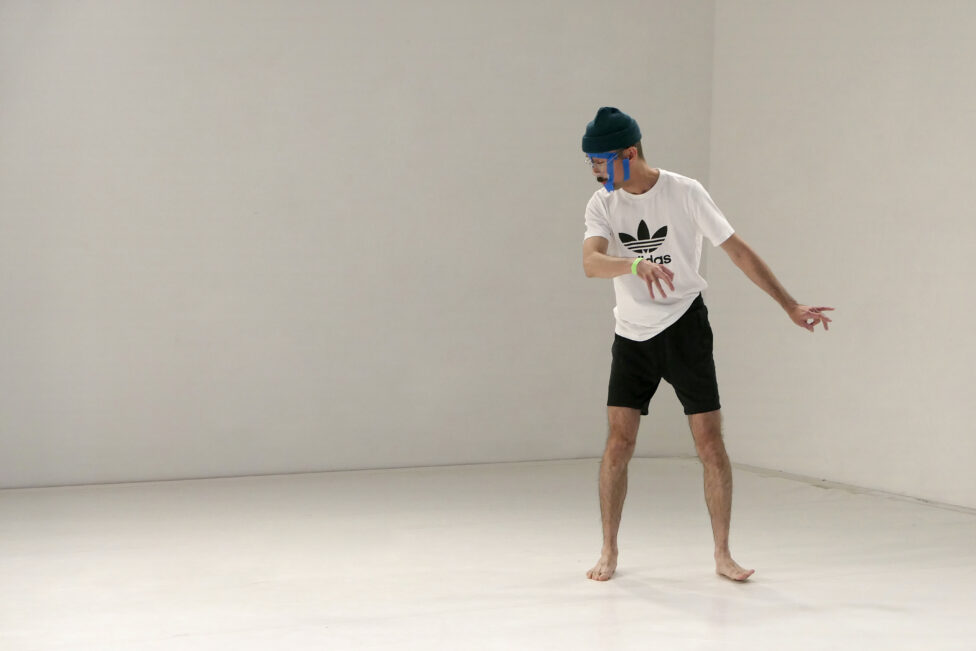

Photo by: Chris Cameron @MANCC_fsu

[ID: Mina Nishimura, who is dressed in grey pants, a white shirt, and a white beanie, rehearses in an open space with leaves and water dusting the ground. One foot is slightly forwards, as though about to take the weight of her next step. Her shadow is cast in a narrow line behind her.]

GPT: It makes me think of the three mysteries in Buddhism. The mysteries of speech, action and thought. It’s like, they’re mysteries, because, at least this is my interpretation.

MN: Yes!

GPT: We don’t really know where these things–speech, action, thought–come from. We can observe. We can observe the things we say, do, and think, but the source of them or where they come from within ourselves is always unknown in an experiential sense.

MN: That’s true. Yes! Then emptiness becomes a space of potentiality. A space for open possibilities. If we are embracing this empty space, then any things can arrive, any things can happen. We don’t know where that speech, the thought comes from but they can arrive in freer forms. If we successfully can create this soft space of emptiness, more things can arrive. More things can happen.

GPT: Or the thing can pass through you?

MN: Yeah!

GPT: If you’re a formless vessel where things, sort of arrive, pass through you, then they leave.

MN: Yeah, exactly. When you’re full or when you are already established as a kind of closed organization, then it’s really hard for anything to arrive, to come to you from outside.. because you’re already an established solid thing. But when you are in this kind of a fluid, soft space, then a lot of things can be welcomed by you. That’s why I consider emptiness as a space of potentiality, a space for possibilities. More new things can come and go freely.

GPT: Where do you see this fit into things? Like, where do you see this fitting into the trajectory of your work? Because you’re working on a few things, right?

MN: Right now I’m here [at MANCC at Florida State University] working on a duet with Kota Yamazaki. This is our almost first official duet.

GPT: Oh, really?

MN: Yeah! And I think the work is definitely connected to all those things we talked about. A thing is also — Kota is my teacher and we share many practices. It’s a very special kind of relationship and situation. So it has been a little difficult for me to do a duet with Kota. It’s a… maybe a cultural thing like..it is a little hard to dance with your teacher.

GPT: Right.

MN: But now I feel more ready to dance with Kota one-on-one. Because both of us share the common butoh-grounded practice which I’ve been doing a while by now, and with this piece, we can really push the rigorous form and butoh-grounded practices to the extent which we have never pushed before. Because Kota has been working with performers with different backgrounds. And I also have been working with, you know, people from here. But this duet is very different as we have the common practice in our body. So we are trying to push rigorosity and specificity of the form further. In this, we are working with this idea of a weather-like body, which is deeply connected to this idea of fluid nature of being and a “subjectless body,” like no self.

Instead of determining and making an action, those actions keep happening to you like a fluid phenomenon. And your way of being just keeps changing. Sometimes a form itself carries a specific modality and almost a character or a personality, and holds an internal landscape. So when I pursue the form rigorously, a specific internal landscape comes within it. And when I change or shift the form, the internal landscape also changes which makes your way of being keep transforming.

And another project, which I don’t have any materials on yet, [laughter] is called Mapping a Forest while Searching for an Opposite Term of the Exorcist. This project is also very much connected to what we just talked about. I’m exploring a specific physical modality, a way of organizing our body, and movement practices, which condition our body to be available for any potential outsiders to arrive. That’s why the title… I’m searching for the opposite term of exorcist… because exorcist, like, tries to get rid of evil spirits that possess your body. And of course, you don’t want to be possessed by an evil spirit! But including those kinds of the invisibles– invisible comers that are considered as jerks or marginalized or not welcomed —those things or beings can also arrive, like anything can arrive. At the St. Marks church where this piece is going to premiere, I’m trying to connect to those invisible inhabitants or spirits or not so visible spaces like peripheral spaces, where people tend to ignore or don’t see. I guess I’m trying to activate and surface invisible realms to the physical space and see how they’re going to recondition our body. The way of being…

GPT: It’s kind of like– Do you know the Hungry Ghost ritual? This is hyperniche.

MN: [quietly] Hungry ghost? Hungry ghost… that sounds so interesting!

GPT: It’s this ritual for after things die. Your lifeforce is supposed to go back into the ether, or like the, I don’t know, the circle of life after you die.

MN: Right.

GPT: But people that have strong attachments to things in this world won’t be able to let go, and so their energy clings on and stays.

MN: Yes?

GPT: So there’s this ritual called something like The Hungry Ghost ritual. You invite all of the ghosts clinging onto this world and try to get them to return to that ether. The general idea is to return to whatever that ether is. So you try to provide them some insight from the Dharma. Then with that new knowledge or insight they feel like they can let go and return into the cycle or something like that.

MN: Oh, my God, that sounds really scary. But also exciting.

GPT: Yeah. It’s funny to talk about these things, because different people have different levels of belief. Like some people I know 100% believe this kind of stuff. While other people are more like, ‘Yeah, sure. But not really, though.’

MN: Wow, yeah, I’ve been really interested in connecting to those invisibles… not necessarily a ghost. But, you know, something, we don’t see. I believe there are a lot of things, you know, we don’t see. And they are a huge part of our world and our reality. I would love to be able to access that part of our world. Yeah.

GPT: There’s this other thing in Hannya Shingyo, where it kind of disqualifies all of your senses.

MN: Right?

GPT: Where this world, or what’s observable with your senses, isn’t necessarily the true ‘world’. In the empty state of things you can reassign or re-imagine yourself in a context outside of the five senses. Like in a ritual practice it’s said that a practitioner can become a buddha or bodhisattva in that meditative or ritual space. And similar to the Hungry Ghost thing, I’ve found that some people really believe that is true while others think of it more as a metaphor.

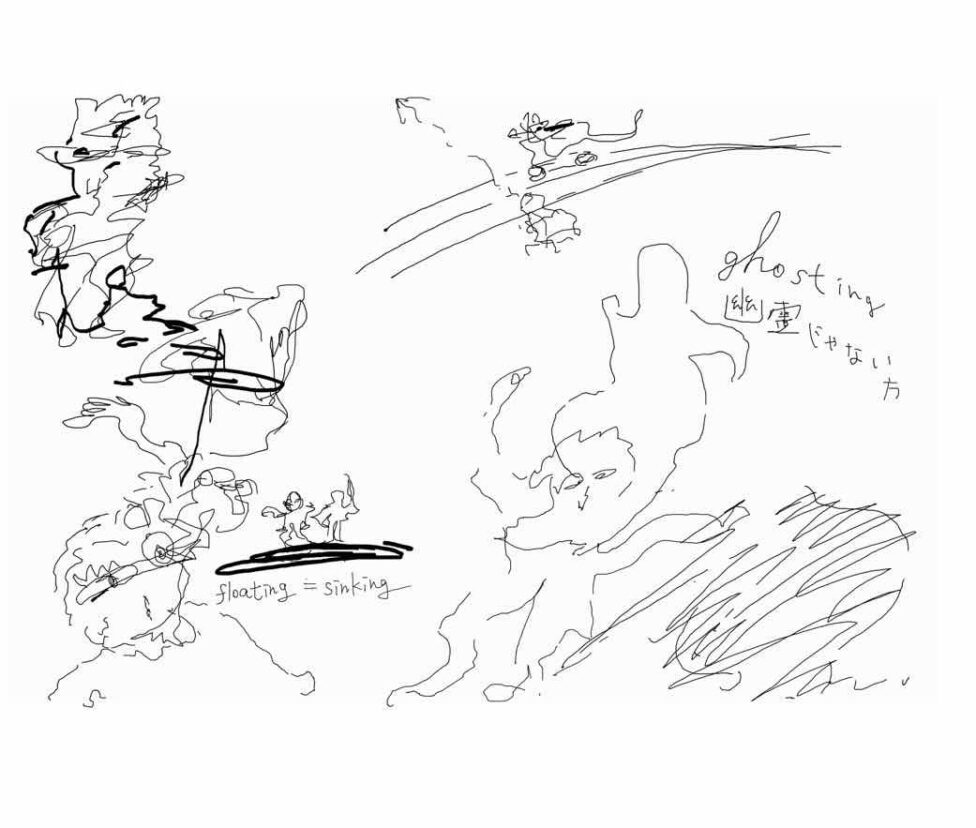

Ghostly Score by: Mina Nishimura

[ID: Black and white digitized drawing and writing of Ghostly Score by Mina Nishimura.]

MN: Wow. That’s so cool. Also, it’s a completely different dimension. And there are also physical things that we just don’t notice. Like, for example, lichen! I’ve been talking about lichen or moss a lot recently because of my friend who is obsessed with lichen. They’re just everywhere. They grow on every surface. But if you don’t pay attention, you don’t notice them and they almost don’t exist in your world although they are there all the time. If I don’t notice or sense those things, you know, they can’t exist in your life. But once you start paying attention, you realize that it’s everywhere. And that completely changes your world. I think there are so many things like that. It can be so overwhelming if you try to notice everything! But I’m interested in re-imagining this world through those things we have been over-seeing or marginalizing because we thought they were not important, necessary or needed in your life. Yeah. And they are connected to social, political dynamics and issues. Like sometimes… for example, homeless people, they’re there.. but you’re trying to ignore them sometimes. Or try not to see them. You see them, but you try not to connect to them. So, they don’t exist in your life, your world. And I think there are so many histories or so many, like marginalized bodies like that. Or forgotten. Or ignored. I’m trying to connect to those marginalized things, bodies and beings that tend to exist in a peripheral, or under-surface space in our life. And I feel like Butoh is very much connected to those marginalized, ignored or unwanted bodies… Butoh carries the image of, you know, like a decaying body, weakened body, dying body, aging body or abandoned body. Bodies people usually don’t want to see.

GPT: Oh, yeah, that reminds me of Shakyamuni too.

MN: Shakyamuni Buddha?

GPT: Because he was the Prince and was totally sealed off from the world growing up. Then when he went outside the palace for the first time and saw a sick person, an old person, and a dead person – these were totally new concepts to him – and it completely changed his perspective on the world.

MN: Oh, yes. Before he went out into the world, those people didn’t exist in his life. And I feel like there are so many beings and things like that, you know, in the world. Things that don’t fit into or fall out of this kind of rigid structure of the world.