Katherine Brewer Ball: I first encountered your work when a friend had sent me a link to your Henry “Box” Brown: FOREVER piece, the performance where you reperform Henry “Box” Brown’s escape from slavery, only you do it by trying to ship yourself throughout D.C. at various post offices by covering your body in stamps. And I’ve been thinking a lot about stories of escape that get told, and which stories are popular and get retold. Henry Box Brown’s story is an interesting one, because of the kind of spectacularity of it and also because of the ways in which he was also critiqued by abolitionists of the time like Frederick Douglass for being ostentatious. He told everyone how to do it so they couldn’t re-enact his escape. Thinking about Henry “Box” Brown: FOREVER, I’m curious, do you consider that a performance work?

Wilmer Wilson IV: That’s a good question. I wouldn’t say I consider it a reperformance of Henry Box Brown’s gesture. I like to think of my work as maybe staging irruptions of history back into the present, or making space for these fragmented moments in the archive. There’s a kind of a spectacular quality to the conversation surrounding his escape that is certainly part of the unending horror of slavery, alongside slavery’s mundane boredom. Part of what I was trying to do was to visualize the interiority of the gesture. It’s like a performance that can’t be seen. Thinking about doing a gesture that is so spectacular and invisible at the same time is a dichotomy that was really important to me. I try to gather together fragments of everyday social relation into these skins or films, and so part of the piece is to imagine an absurd or fantastic visualization of the interiority of Henry “Box” Brown’s gesture. The stamp skin is like a viewing device. It’s important to be using my body, to anchor the conversation in the discourse of the body. I feel like there’s a fluidity between performance work and work that deals with objects or materials. So, I’m making work from an understanding that slavery is continually reducing bodies, flesh, into objects. I’m trying to imagine what a performance that only involved objects would look like. And then, conversely, trying to approach objects as if they have a life of their own or they’re capable of making conversation or of making demands.

KBB: Visualizing the interior and thinking about the stamps gives you a way into an inside, so it’s a private performance in that sense. Or a private work.

WWIV: The stamps are enclosing my whole body and it veils an implied interiority. As a field or a skin, they look absurd, and begin to annotate the everyday. The coating turns a stamp into this skin-like or flesh-like field of meaning. Being able to tether something like flesh to an everyday object like the stamp is an important visual quality of the work, an exterior quality of the work.

KBB: You do that with your other “skin works,” too, with the “I Voted” stickers and the Band-Aids, the hydrogen peroxide strips and the black Post-It notes. That one is such an interesting piece, you don’t get the sense of texture or depth with the Post-It notes. It is like a redaction.

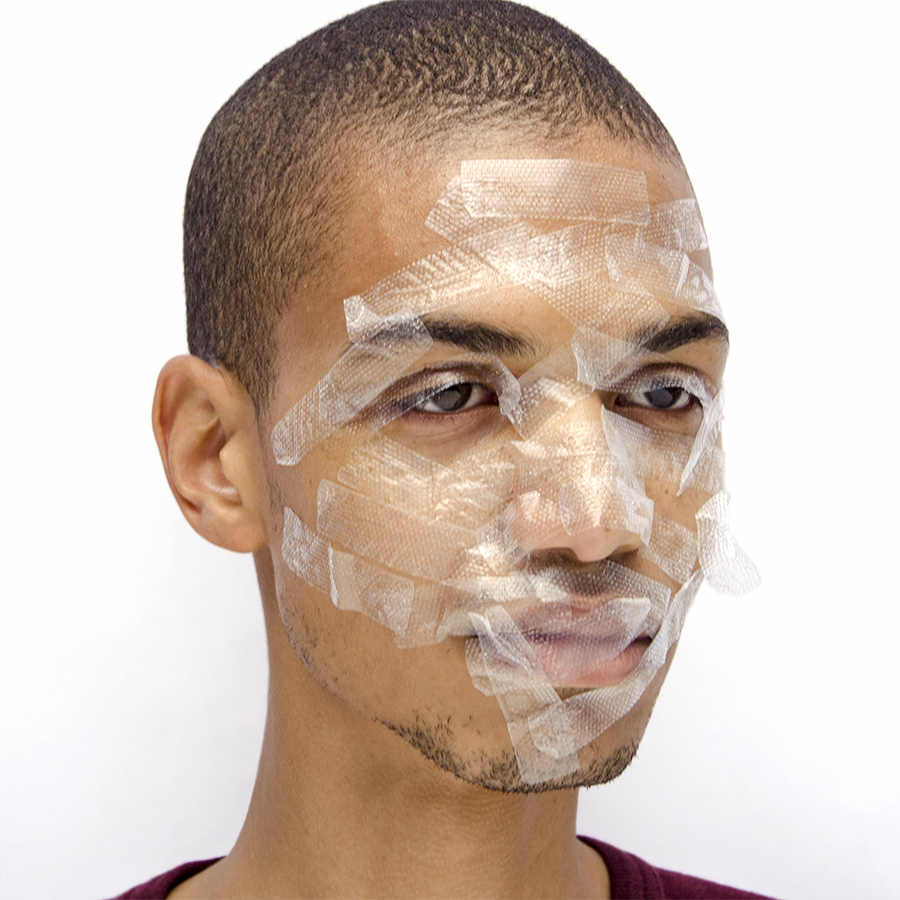

Wilmer Wilson IV, Study, Portrait with Hydrogen Peroxide Strips (2014). Photo: courtesy of the artist.

WWIV: Absolutely. Portrait With Hydrogen Peroxide Strips and Black Mask are both interesting in that regard. Taking the strategy of opacity and translucency. Black Mask is also trying to visualize this impossible thing to see. This essential visual notion of blackness. The frame places centrality on the face, which feels like the locus of personhood, and the paper covering my face flattens out those details of personhood, but also sets up a jagged, complex silhouette of a head. That push and pull between sub-human or superhuman was really important to me. I think of my work as trying to reach outside of the discourse of the human. And then, similarly with Portrait With Hydrogen Peroxide Strips, I always thought it was really funny that the resulting covering that I made for myself was actually white, even though the strips are visually clear. It has an essential quality of whiteness, a sort of biochemical whiteness. Having a slippery or untouchable quality feels appropriate to the pervasiveness of whiteness in the everyday. Also, the bodily discomfort in absorbing chemicals of the hydrogen peroxide strips maybe point to the labor as a non-white person in trying to approach whitneness’s levels of access

KBB: The toxicity of biochemical whiteness. It’s extra taxing.

WWIV: It’s like invisible, delayed and spread out over time. Interesting to think of toxicity as being a time based state.

KBB: And what are moments of interior relief in opposition to the toxicity.

WWIV: Absolutely.

KBB: So, these earlier pieces, they’re from 2011, 2012, and start with questions of visibility and objecthood and refusal, that’s the opacity you’re talking about. And they’re centered on your body. It feels like your more current works are shifting a little bit away from your body as the center of questions, your body being on the front line.

WWIV: I’m glad you made that observation because I feel like that’s been a really central question to me about performance. It became clear after I used my body a certain number of times in my work. I’ve found it increasingly difficult to devise strategies of performance that could be understood as transferrable strategies to other bodies. Somehow my performance gestures always stuck to my body for viewers, and I am certainly not interested in denying my historical, cultural, social specificity, but I think my body maybe became an outsized visual focus in my performances where it set up a distance between viewer and performer that felt artificial to me, or maybe it absolved viewers of certain types of complicity they have in the construction of objecthood. I think in this new work, like you’re saying, the strategies are pretty similar. Creating these coverings or skins for bodies is coming from a similar impulse of trying to care for the interiority of the subjects. I feel like part of that impulse from me in recent years has been to make clear the potential of a community of bodies. I want to be developing strategies for a social fabric of bodies.

Wilmer Wilson IV, Black Mask (2012). Photo: courtesy of the artist.

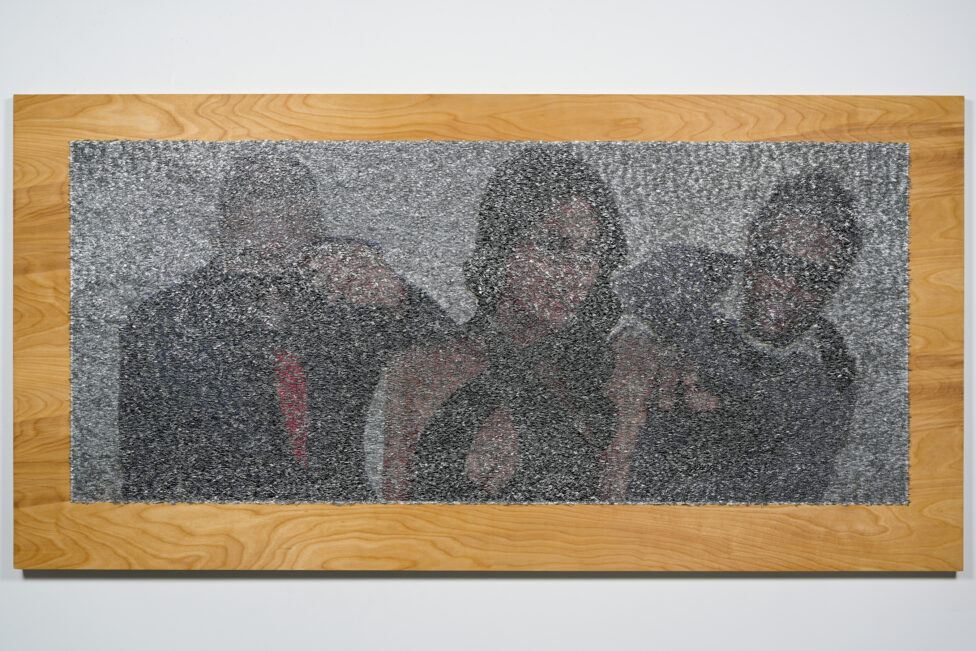

KBB: With these staple-based works, like the pieces that were at the New Museum Triennial last year, it sounds like they involve a durational process of stapling. And there are these patterns that appear in the work: rays of light or waves of an ocean or the kind of sequin pillows that you can get at 99 cent stores. I guess that’s the “social fabric of bodies” you’re talking about, with the overlapping textures that you have in a lot of your work. You create these skins that you’re talking about, these filmic surfaces. And thinking about the staples as a viewing device that’s also a filmic surface is really interesting because they’re so textural and they hide so much of the figures beneath them. But it’s also interesting to think about them like a lens, a viewing device that’s not about visibility, availability, or objecthood, especially when it comes to the history of anti-blackness and consumption.

WWIV: The patterning has been interesting. Part of it is an impulse to make clear my own mediation of the images, like a record of my intervention. But also I wanted it to be a conversation with the design language of the flyers that the figures are embedded in. For this new body of work Slim… you don’t got the juice that I’m showing at Susan Inglett Gallery, the pattern is gonna be a lot more randomized and I think in some ways it’s an attempt to set up even more opacity. To set up a separation between the staple surface and the image underneath. That hopefully begins to emerge as a viewer is engaged in the labor of moving around the work. But also, I don’t want to abandon the body. I want the surface to remain a viewing device, like a lens and not like a wall.

KBB: And you call these portraits, right?

WWIV: I would say they’re portraits. You know, I wonder if it’s possible to expand the purview of representation without abandoning the body. That’s been a pretty consistent question in my work, from Henry “Box” Brown: FOREVER to now. What does it look like to employ these facets of historical specificity that don’t lend themselves to a fetishization or voyeurism of the interiority, however indexical or not, of the figures depicted. So yes, I feel my project is one of portraiture in an overarching sense.

KBB: I like thinking of retaining portraiture not only like a representation to translate or give to an audience. It makes me think of Douglas Crimp, in “Our Kind of Movie”; The Films of Andy Warhol he writes about this one film called Blow Job where it’s just a man craning his neck. It’s just his face, he’s moving in and out of light. One of the big questions that Crimp asks is how you create a really beautiful portrait. And he says, “this face is not for us.” I’ve been thinking a lot about portraits being exciting not just because they give over the subject or object of the portrait, but because they’re beautiful, too. But consumption is also caught up in history’s own way of white supremacy, and the desires that are inside of them. So, I like thinking about the portrait as a beautiful kind of project, but one that is challenging in some way, as well.

Wilmer Wilson IV, RID UM (2018). Photo: courtesy of the artist.

WWIV: I think a lot about that in relation to photography in particular. Maybe it feels ridiculous for someone like me who thinks of myself as a photographer to say it, but I feel suspicious of beauty in photography or in portraiture because it feels so fraught. I think about the role of photography or photojournalism in perpetuating fetishization of groups of people over the last hundred years. I feel a vacillation between an impulse to care for a subject and an impulse to violently deconstruct a fetishized object, which often is entangled within notions of beauty. This is a really animating force for me. Sometimes it feels close to cancelling itself out, you know? And it has also been pretty hard on my body, where something like Portrait With Hydrogen Peroxide Strips is sort of flipping between violence and care. Maybe I’m bound to go on to do that forever, but I hope in these staple works, at least, there’s just as much beauty, like an annotation of the beautiful sort of care along with this violent redaction of fetish objects. I don’t know if it’s possible, but it seems worthwhile to try.

KBB: Maybe beauty is too heavy of a word, with the Kantian implications, I don’t know where that specific term comes from. Can you talk a little bit about your other new work, the photographs that are also performance?

WWIV: I’ve been doing this performance of running through urban space at high speed and taking photographs of city space. The photographs all come out skewed and blurred. I’ve been really interested recently in the monumental physicalized results of public narratives of history and then also of less iconic notions of what a monument is, and who a monument is for. You talked about annotation and redaction earlier and I think a lot about that in my work. Seems like part of my project against portraiture is to try to identify the line at which visual information is taken away from an image and our imagination or subconscious rushes in to fill the gaps. That feels like a really prominent dynamic with viewing a monument that’s vaguely uncomfortable. You begin to fill in information that is missing from what is visible. In some ways I want to employ the violence of redaction against a public monument, that received notion of what is public shared history. In the scope of my show it seemed important to have these obscured, once-monumental figures alongside the staple works which annotate ephemeral images with a care-filled labor. It generated as a gesture in a performance series that I’ve been calling Running Tours. It bases itself on tourist guidebooks or a succession of iconic moments in a city. But this performance is a kind of running without stopping. So, it resulted in these books that are a documentation of city space, mediated by a body running. And the impulse to run through the city space is also a question: what is it about the city space that compels the performer to never stop, to not devote enough time to standing still to make a clear image? It feels ominous to me.

KBB: I’m thinking about what you were saying earlier, too, about the social fabric. It’s like, how do you run through with a sense of care but also a sense of violence toward the monumental? Are your staples pieces about a certain care for things that are both boring and spectacular?

WWIV: A mistrust of not just the fetish, but also of the grand narrative of shared history. I just have a lot of questions about whether ephemeral things are ephemeral by nature or kind of externally relegated to the status of ephemeral, you know? And also, on a base-level, I want to regard things that seem worthless, that have expired, things that occupy the world of trash. To be able to augment their presence in public space. I hope that materials have an accessible, every day entry point. It’s really exciting for me to have people recognize that it’s staples what creates this visual surface. It sets up an entry point of understanding one, the labor involved, but two, the strategy of annotation and redaction, and its usefulness in the everyday. The forms are already there. Staples accumulate in various public places, like on telephone poles. That’s the groundwork for these strategy already existing in public space.

KBB: They were community flyers, right? Underneath those? I hadn’t really thought about the staples on poles, but of course. There they are.

WWIV: It’s interesting. It feels like an archive to see this accumulation of staples on a pole. An archive of a circulating public discourse happening. It’s exciting to me to think about ways of employing that labor to certain protective ends, or certain care-filled ends. I have complicated feelings about the Situationists, but I really feel influenced by the notion of détournement on a basic level, of taking a thing and seeing that it has all these ways it can be used, it’s just a matter of deciding to apply it in an uncommon way.

Wilmer Wilson IV, Across the blue concrete, red embers fly to me (detail) (2019). Photo: courtesy of the artist.