Urula Eagly: In Terrific Freight you worked on transmitting an aesthetic to the performers, which you described in an email exchange we had as “a way of being and perceiving that is more me.” Could you describe how you define this aesthetic experientially, how you communicated it to or coaxed it out of the performers, and how it relates to the idea of “technique”?

Julie Mayo: I would describe the aesthetic experientially as embodied paradox. In Terrific Freight we worked with the specificities of moments, not defining them in a narrative way, but understanding the quality of them, the how of them, allowing for these moments to change, often quite quickly, and also being able to let go of them. The work is also to engage in the moments completely, while being aware of each other and the audience. I think those things are the “more me” I was referring to in that I am usually holding a lot and I ask the performers to cultivate this kind of perceptual acuity. Doug (performer) described it as carrying a lot of baskets, so many that you can’t hold them all. Sometimes you drop one, so you pick it up and bring it back into your awareness with all the other baskets, and continue. Additionally there’s an intimacy and attention to detail that I’m communicating. It’s a layered way of perceiving that I think enables an illumination of that which is often underneath. But doesn’t negate surface. It’s finding the energetic location of things. The “technique” involves a lot of undoing and recontextualizing. This includes an ability and willingness to part with a particular kind of continuity as a kind of given progression or expectation. There is also often an “undoing” (or putting it on layaway) of learned, codified dance vocabulary, sometimes to bring it back, reframed or juxtaposed.

Tere O’Connor: What kind of procedures do you engage to cull, categorize and sequence, the flow of movement and imagery born of your embodied excavation of consciousness?

JM: There’s a lot of instinct and intuition involved for me with all of these things, which you know. Most of the movement is culled from improvisations in which the performers respond to scenarios I offer or questions I ask them. This raw material comes from the performers almost exclusively. In our improvisations I started using the word “scenario” instead of “score” as I find it opens up more possibilities. Somehow “score” elicits a kind of movement that feels “stereotypically improvisational.” Sometimes things do come from outside the studio, like the chorus from Lady Gaga’s “Telephone,” that I sang to myself for weeks in a cranky, high-pitched voice. This ended up being incorporated into what I was making at that time. I like the strategy “begin anywhere.” Anywhere is, of course, somewhere. This dictum invites a subjective, qualitative approach to making that speaks to me.

I’m not sure about categorizing. There are a lot of different modes in my work—gesture, codified Western concert dance movement, speaking and altering language, pedestrian actions, behavioral attitudes or affects, sounding, feeling states, pop references. I have an inclusive palette for what types of things my work can contain. It’s not that anything goes, rather I’m asking what belongs in this world? Equally important is its inversion — what doesn’t belong in this world? If I can find the articulation of the how and when inside my relational process, many things are possible. I do keep a notebook and take notes, scribble drawings, name movements and sections. But the notes are used more as part of the process than a document. I say this because I don’t always refer back to them. It’s like the act of writing itself provides a space or invitation to be written over but through an inscription in the dance. I do revisit the notes periodically, but each time I do so much has changed in terms of my consciousness. It is a little like a palimpsest.

Sequencing for me is very much based on feeling it out. The procedural tool is a human barometer. Where does this go? And for how long? While what else is happening? This is kind of the roux for me in a dance I’m making. It’s almost like playing with human paints that speak or sing, or moving into an awake kind of dream where the logic is not gleaned through analysis but through subconscious assimilation.

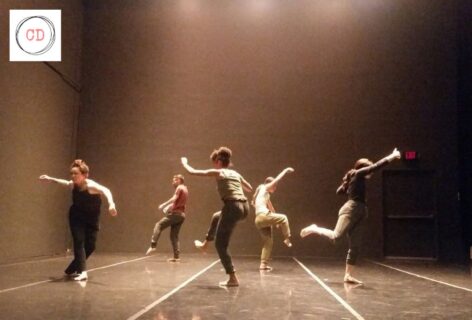

Doug LeCours and Jessie Young in Terrific Freight. Photo by Madeline Best, 2018

Christy Funsch: How did the work in the studio with the performers compare to the work you did outside of rehearsal?

JM: I didn’t really work outside of the studio. Not in an active way. The yearlong process for Terrific Freight encouraged a back and forth seepage where our studio time remained with me between sessions and the daily life goings-ons during our off-time infused what got brought into the room. I think this is always happening in any process, but there is intention on my part to include it, not necessarily directly as content, but acknowledging the non-separation of our lives and what we’re making. I love a residency situation in which the time between sessions is minimal. It brings a kind of rigor to our work time that is much harder to get at in the city with the two or three times a week thing. It’s also more challenging in a sense because the process becomes concentrated, there is less two-way seepage, and the work starts to leak in on itself, but in a good way, as it becomes itself.

CF: Why these performers, at this time, in this work?

JM: Time-wise, it aligned. I came to this group of performers in different ways. Jessie and I had worked together before (on several pieces) while we both lived in Chicago. Over time we both landed in New York and though it had been a while and many changes/experiences for each of us since working together I had a hunch it would still be a good fit. And it is. I met Mark in the first workshop I took with Deborah Hay in 2016. There was something about their countenance throughout most of the workshop time, a delicately furrowed, inquisitive brow, along with an ease in entering into whatever we were doing that piqued my interest. Shortly thereafter I saw them perform in their own work at JACK and they had an open and unarmed presence that was lovely to see, so I asked them to work on this piece. Excellent pique. I met Doug in a different Deborah Hay workshop the following year where we ended up working together in some of the group things. He had expressed interest in being in my work and down the road I invited him to preliminary research sessions for this piece with other performers. He had a quiet intensity about him, was hard-working, open and funny. Win, win! Regarding your question why these performers? Well I couldn’t have known this before making the work, except in the case of Jessie, but what I found was that each of these three performers were able to rigorously engage in a distinctive poetic logic, a sensibility that I’ve been cultivating that asks for a lot in terms of focus, trust, and courage. Jessie stated “Your process is deeply challenging for me because it puts me up against myself, not like in a confrontational way, maybe more just like looking at and feeling myself and having to sit with what the reality is and, perhaps more challenging, feel that reality in constant shift.” I hope it gives back a lot as well.

Jessie Young, Doug LeCours, and Mark McCloughan in Terrific Freight. Photo by Julie Mayo, 2018

CF: How does the work account for the totality of these performers (people)?

JM: I think Jessie, Doug and Mark are all exceptional performers, meaning in this case, that they are able to access performance modes or ways of being on stage that I put a lot of value on. I don’t think of “performer” and “person” separately in that, hopefully, a performer always brings to bear who they are and how they are perceiving what we are doing in the work to the work. There can be a lot of range in performance/person/persona…I work to cultivate specificity within this continuum and it involves the person performing themselves, emphasis on *selves,* which includes not self. Sometimes the range with this shifts over time in a process and in this case it did, in the best of ways. More explicitly regarding the totality of performers, I’m never working with just “bodies.” Well, of course nobody is, but it seems worth mentioning as so much writing on dance (oxymoron) uses the language of “this body” and “that body.” Body, body, body… insert black, white, precarious, female, Cunningham. “Body,” used to refer to a performer or groups of people, makes me imagine a headless body and it has just enrolled in a Performance or Critical Dance Studies PhD program. Funny but true. On the one hand it’s great that there are a number of programs now for this study, but I feel like these programs also serve to legitimize an art that doesn’t need legitimizing. And I wonder what effect academic discursivity has on dance-making when artists feel beholden to “fit” a work into a particular paradigm, theoretical construct or start from these “places.”

J. Dellecave: Julie, first off thank you for and congratulations on Terrific Freight! As always, I am compelled by the way your performances craft familiar and nuanced, but ineffable worlds. For me these worlds enact their own logics, which sit inside the realm of knowing, and outside of meaning-making or narrative progression. In Terrific Freight I was struck by a particularized kind of harmony/harmonizing—in the voices of the performers, the arc of the evening, and the performance of the ensemble. Could you speak to if and how harmony and/or harmonizing came up in your process/performances?

JM: I hadn’t thought of this particular word in relation to the process of Terrific Freight but I’m glad you did! I’m glad because it is a good word to describe a practice that developed in the studio about midway in our year working together. I coined the practice “worlding.” The environment I set up in the studio is pretty specific. Of course there’s a rehearsal culture to all work being made. For me it varies with who is in the room as to what is needed, and/or possible, but in my work perceptually warming up and letting go of self-consciousness is equally important as warming up the body. “Worldings,” so named because of the broad scope of what these could be became a method of coming together in the space and helping us to enter into the microcosm we were building. A few examples are working with “not task” (which came out of working with tasks); non-sequitur speaking in stillness and while moving; and borrowed questions such as Deborah Hay’s “what if there is here?” or “what if there is no there there?” I see our worlding practice as a kind of harmonizing that came from our collective action of offering different “warm-ups” and helped grow the sensibility of the work. Mark (performer) wrote about this notion of harmony in our practice, “As we went on, the worldings also felt useful because they became ways for us to practice speaking about our performative experiences and trust that the others would be able to follow the poetic logic and not need a more traditional logic to understand something of what we were trying to say about our experience.”

Doug LeCours and Mark McCloughan in Terrific Freight. Photo by Madeline Best, 2018

Jeanine Durning: Having seen a lot of your work over the years and also having seen you work, I noticed a significant shift in how the structure unfolded in Terrific Freight. Of course, these things always come in a kind of progression and not out of the blue but in your previous works, I was always aware of a directorial hand, even in the midst of emergent strategies that I know is one of the foundations of your work. But in Terrific Freight, I wasn’t aware of the power structure of the director, or the need to channel switch or to exhibit a tangential mind. I perceived much more of an ongoingness, where things were unfolding in a time inherent to the thing. Which is not to say that wasn’t a directorial choice. What would you attribute to my reading of Terrific Freight’s structure in that way?

JM: Yes, I’ve worked with emergent strategies for a long time. I’ve never felt a need to exhibit anything about my mind through my work. I’m just working. I am at home, and challenged, within a framework that is simultaneously emergent and directorial. Maybe what you’re referring to in how the structure unfolded in Terrific Freight, in relation to what you said you’d always seen differently, is that the feeling of its overall-ness is more one thing than in past works. I’m not sure. There are many affective shifts for me in Terrific Freight, but when I zoom out there is a kind of paradoxical weighted/sturdiness and fragility that is consistent throughout and constitutes the wholeness of it for me. This is a structural thing, but equally so a performative one. Jessie, Doug and Mark carried the load and the delicacy all at once. They really had it. They were it.

I think I know what you’re referring to as “channel switching.” I’m calling this rhythm. These rhythms are created from moving from one thing (your channel?) to another (as opposed to the rhythm that makes up or is inside one thing). These things/events/modes come in different sizes and durations and often have a certain discreteness to their action or eventness. Then they change. Another way of saying this: it is the rhythm of moving amongst many things, that are appearing and disappearing.

Julie would like to thank Ursula, Tere, J, Christy and Jeanine for their ongoing dialogue, their insightful questions, and their persistent art-making selves.