Kristin Poor: Congratulations on winning the Kyoto prize.

Joan Jonas: Oh thank you.

KP: It has been a really big year with this prize and the stunning Tate retrospective.

JJ: It has. I’m overwhelmed.

KP: Can you talk a little bit about the process of putting together your Tate retrospective, and what you were hoping that show would do?

JJ: I never think a show is going to do something, it’s bad luck to anticipate results. I did the show at the HangarBicocca in Milan in 2014, which was a precursor to and an inspiration for the Tate show. I spent at least two years working on the show and talking with the curator Andrea Lissoni, who was also the curator of the show in Milan. That was a much larger show. I always make models, or have them made. I work with Sketch-Up files, with my assistant Jin Jung, to reconstruct the pieces inside the spaces. With Andrea, I had to choose which pieces should go in. It takes a lot of preparation. The details at the end are just unbelievable. It was very different to show this work at a museum, at the Tate, than it was to show it at HangarBicocca, an airplane-hangar-like space with no walls, because of the different spaces and arrangement of the rooms.

KP: You’ve had these chances to do survey shows over the years. How do you find that that affects you? Do you find that you reconfigure, and look back?

JJ: No, no, I don’t, I mean while some rearrangement is involved, there’s no time to reconfigure the pieces that you choose. I choose them—they’ve been figured out. It does bring back memories, but I really try not get involved in looking back. It does take up your mind in a way. I was simultaneously working on reperforming four earlier works, as well as a new performance, the oceans piece (Moving off the Land). The performance aspect at the Tate was different from past surveys, because of the input and collaboration of Catherine Wood (the Tate’s Senior Curator of International Art and Performance) and the performance department at the Tate. They wanted me to do the mirror piece (Mirror Piece II, 1970/2018) and the outdoor piece (Delay Delay (London Version), 1972/2018). We had also talked about Mirage (1976), because the related installation wasn’t in the show, and the performance with Jason Moran (Modern Working Together: A Lecture Demonstration, 2015/2018) of course would also be included. So I did four performances at the opening, I don’t know how I got through it. In the end I’m really glad I did it. It was very interesting. I’ll probably never do it again, in that way. To go back and do another new performance, Moving off the Land, in the Turbine Hall made a big difference. It required a lot of preparation and work.

KP: Did seeing the works together in Milan at HangarBicocca (Joan Jonas: Light Time Tales, 2014) shift your perspective?

JJ: Actually no. Milan was the first time I shared all these works in one space. It was interesting to see them all together. The show in Milan gave me the confidence to put all the works or installations in the same space and let them overlap. There are so many common elements that run through them, like threads, that I think the audience found it interesting. They got to see these relationships. Yes, that influenced the way I looked at it, my perspective. It takes a while for things to sink it. Sometimes I look at things and I think, “Oh maybe I should go back to that.” But I don’t have a conscious feeling. It hasn’t sunk in yet.

Joan Jonas, Mirror Piece II, performance at Tate Modern, London, 2018. Photo by Lewis Roland. Courtesy Joan Jonas and Gavin Brown’s enterprise, New York / Rome. © 2018 Joan Jonas / Artists Rights Society.

KP: How did you go about putting a performance from the seventies like Mirage back together again? Was it like riding a bike? Did you find that the movements lived in your body?

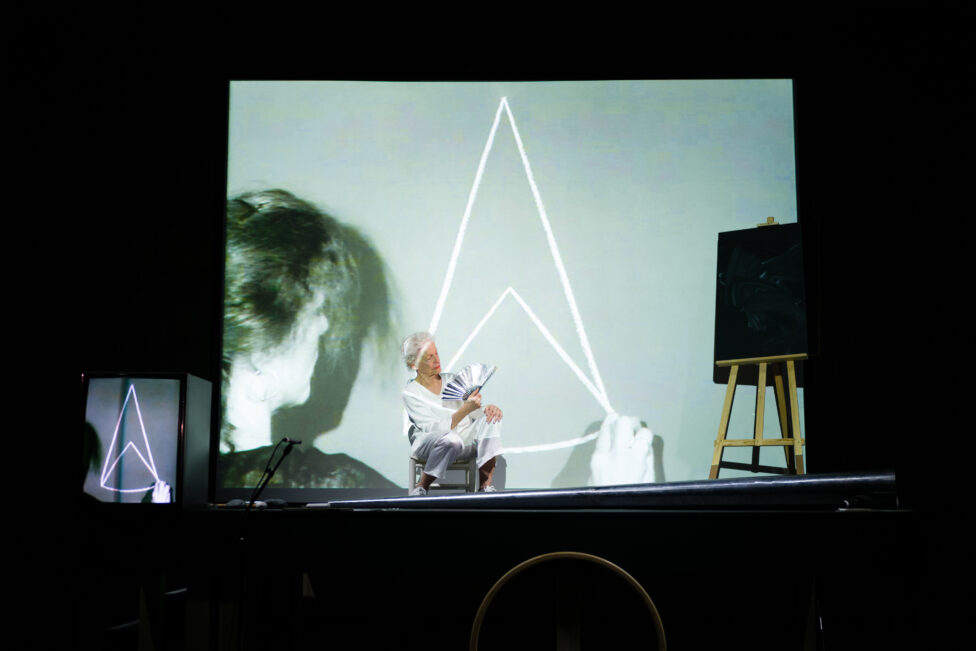

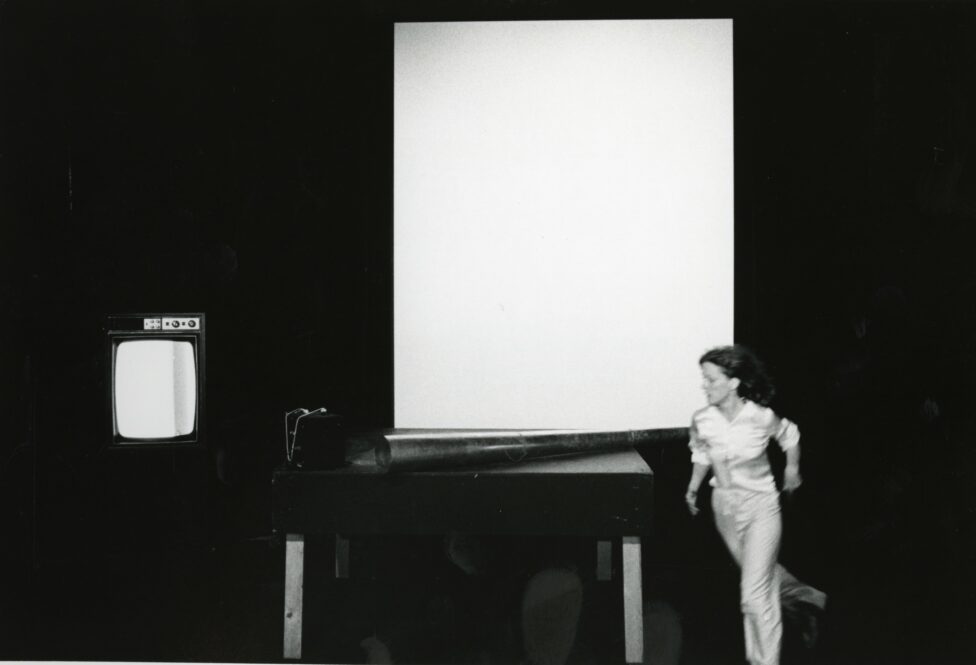

JJ: In no way, no. I thought the scripts that I found were going to be better, but they really lacked information. I worked from the scripts and notes and photographs and props. We had all the props made. We had the stage, we had the area of the stage, here in my loft. We had the costume remade too. I tried to go through all of that and then put the piece back together. I had to do much of the movement differently; I cannot do simple things like sitting down and getting up in the same way I did then. I did a lot of that in that piece. Going up in a headstand, I couldn’t do that. While I was working, it didn’t occur to me that here I am, (or what it looked like, I didn’t see it): me at my age now, me at that age then—such a big projection performing with my younger self. At first, we weren’t going to re-stage Mirage because I felt overwhelmed by all the other works. In the end I decided to do it because I thought it would be important to do, and interesting, and that’s it. Five years ago, I worked with this wonderful woman, Nefeli Skarmea, who I met in 2012 at Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev’s Documenta. I knew when I met her that she could do something to help me. Either perform or to help me direct. She has become the official person to help me redo things. She finds it interesting. I don’t really want to do it. It takes too much time and energy. I’m glad I did Mirage; this juxtaposition of my old self and my young self. I have to look at that and see what it looks like. Nefeli organized the group works Mirror Piece II and Delay Delay, while my first assistant from the seventies Paula Longendyke produced Mirage with me.

KP: One of the things that I found especially beautiful about Mirage is the way the drawing worked. We see a 1970s filmed version of you, and you today, live on stage, both making drawings, together. The gap in years made me think about the way that drawing and memory are connected. Could you talk about how drawing and memory work for you? For example, when you were making the Mirage film, were you drawing from memory?

Joan Jonas, Mirage, performance at Tate Modern, London, 2018. Photo by Lewis Ronald. Courtesy Joan Jonas and Gavin Brown’s enterprise, New York / Rome. © 2018 Joan Jonas / Artists Rights Society.

JJ: They’re partly from memory, and partly from the actual physical filming of the drawing. I spent a lot of time in my loft making those drawings—those drawings of hands, and of magic tricks. I had a magic book. There are some drawings of an arm with a piece of cloth around it. I worked on those drawings a lot before I actually did the drawing with the filming, because we filmed it continuously. Drawing and erasing, stopping and starting. Drawing and memory, I never thought of that. When you say that, what do you mean?

KP: Well, I had read something that you said about a story that you read in a New Guinean Book of the Dead—

JJ: Yeah, I was going to mention that in relation to drawing in general.

KP: There was a story that you once told about how someone had to do a drawing from memory, in order to get past this old woman to enter the afterlife.

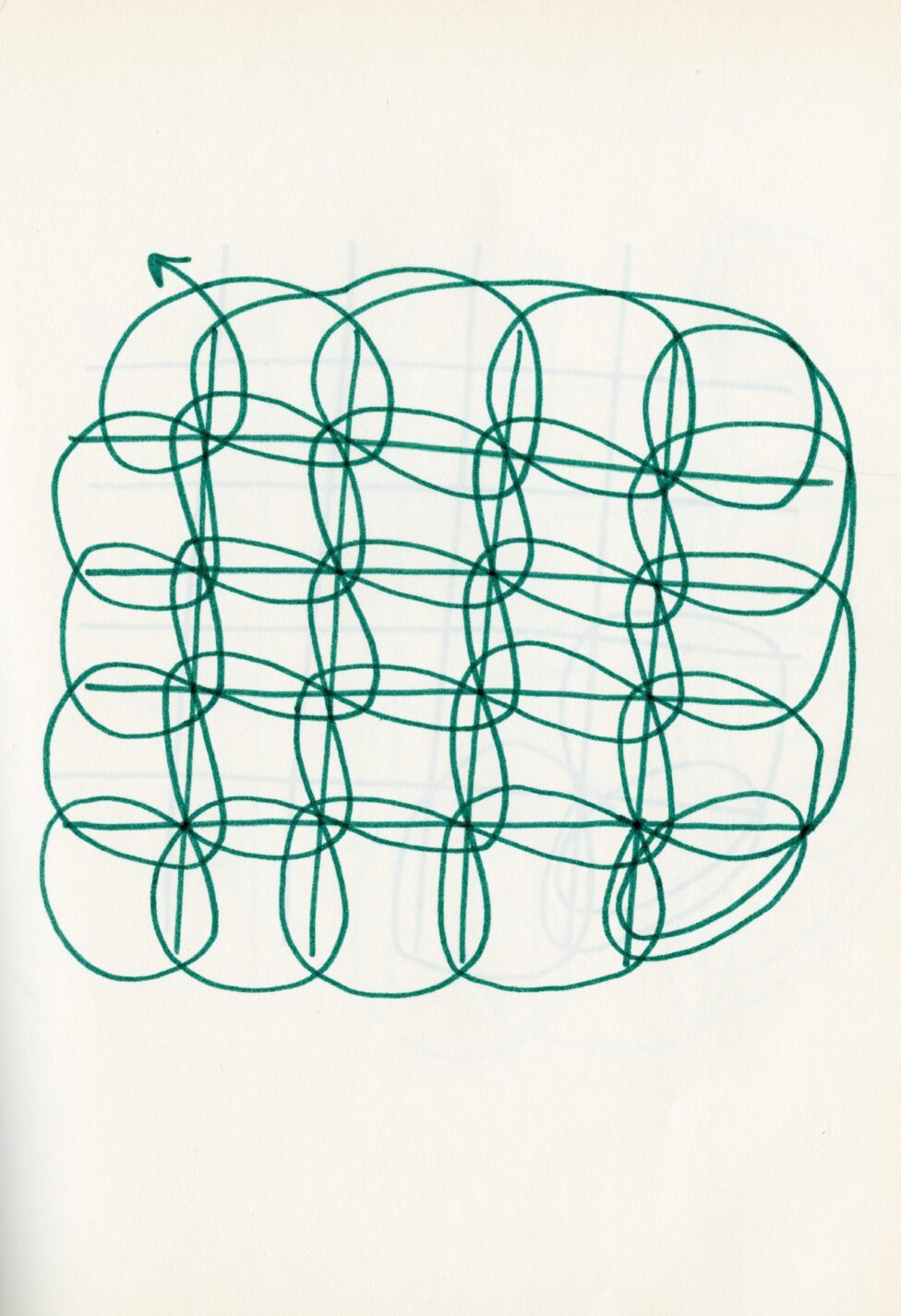

JJ: That’s from this book, Spiritual Disciplines. At the point between life and death, you meet the devouring witch. She begins a drawing. To get through to the next stage you have to complete the drawing. People had to know the drawing and draw it from memory. I didn’t use it that way, but that’s its origin.

[stands to get book]

I have it here. Spiritual Disciplines. These drawings influenced me a lot. I used them over and over again. I use them in performances and then they’re in the Mirage film. I copied them. I memorized them. They’re the one thing from another culture that I’ve copied and used, but I always say what they are. I was also very influenced by Maya Deren’s films about Haiti in which they drew in white patterns on the ground, over and over again. That whole drawing film is influenced by those references. They’re endless drawings, where are these, they’re in here, I have to find them. It was in the Malekulan book of the dead, from a New Guinean tribe. They’re incredibly beautiful drawings. That drawing film was directly inspired by Maya Deren’s films of Haitian Vodou rituals, drawing with white powder on dark earth leading, for me, to chalk on the black board, and drawing and erasing. I was inspired.

KP: This one I remember.

JJ: They’re ritual drawings, so you could use them in a performance. This one is particularly hard to do.

KP: It’s really complex.

JJ: It’s one continuous line.

Joan Jonas, Endless Drawing (from notebook), 1970–71. Courtesy Joan Jonas and Gavin Brown’s enterprise, New York / Rome. © 2018 Joan Jonas / Artists Rights Society.

KP: So there’s a connection for you between ritual drawings and performance drawings?

JJ: These are ritual drawings, and I have always thought that my performance is in relation to what I think of as ritual. From the very beginning.

KP: What connected you to that idea of ritual?

JJ: When I began, I’d already studied other cultures in art history. A lot of visual art comes from ritual. When I first started thinking of doing performance, I related to that ritual, and I studied ritual. I did a lot of research in relation to ritual in other cultures; in the Ancient Greek, the Roman, the Chinese ritual traditions. Japanese Noh Theater comes from ritual. I thought of my work as my contemporary, modern day ritual.

KP: That’s great. To go back to Mirage, and the kinds of movements that you were doing, you talked about the difference between the performance then and the performance now. There’s this really long, seven- or eight-minute passage, where you are moving your arms and legs quickly with your back to the audience. Could you talk about that and how that was different, or what it was like to do that then and now?

JJ: Did you know I spent three months in India, at an ashram meditating? A meditation based on a combination of different ideas, it’s called the Dynamic Meditation. It involved jumping up and down and moving your body as much as possible. Arms and legs in all directions for fifteen minutes. But I didn’t do that, I couldn’t do that, all I could do was run in place in the projection of a ten-minute film of volcanos erupting. That was one of the things I had to alter.

KP: It did strike me how in reading about the earlier performance, that there was no way to really understand what that duration felt like.

JJ: Oh doing that movement? You know it depends on what age you are and what kind of shape you’re in.

KP: And for an audience member to sit for ten minutes and watch. That’s not something you can ever understand from a photograph.

JJ: Yeah, right. Different people have different reactions.

KP: Have the restagings led to any interesting misunderstandings?

JJ: Not yet. People don’t come rushing up to you to say what they thought. They don’t. So maybe at some point some people will start saying something.

Joan Jonas, Mirage, performance at Anthology Film Archives, New York, 1976. Photo by Babette Mangolte. Courtesy Joan Jonas and Gavin Brown’s enterprise, New York / Rome. © 2018 Joan Jonas / Artists Rights Society.

KP: At the Tate performance of Mirage, you said that you knew what the piece meant in 1976, but you weren’t sure yet what the new version meant. Have you had a chance to reflect on that? It’s been a few months.

JJ: I have to look at the video before I can think about it. I went right into Moving Off the Land. So, I couldn’t think about it. I haven’t had a chance to look at it.

KP: Let’s talk about this recent piece, the Moving Off the Land, which had its U.S. premiere a couple weeks ago at Danspace Project. How do you approach the text for a piece like that? You’re often weaving together a number of different text sources.

JJ: I worked on it in bits and pieces over a year and a half or two years. It began in Kochi, India. I collected the text partly from the internet and from listening to the radio, and reading newspapers. And there was an Italo Calvino story in it. The first version I made had a lot of talking. I kept working on it. I decided I wanted to shift from having it be a lecture with some accompanying video, to being more of a performative lecture. Originally, I didn’t include Rachel Carson, but her writing is so beautiful and poetic, so then I included more of her, and I took out the Calvino because I didn’t think it worked well.

KP: Which story was it?

JJ: It’s called “Uncle Fish.” It’s about a family that has just come out of the ocean. The guy is going to marry this girl, but then he introduces the girl to Uncle Fish who still lives in the ocean. Then the girl goes back into the ocean, to make a long story short. It illustrates what I was working with. But I took it out. Slowly I shift towards talking more about the actual animals. I cut down the text, it was edited, more fragmented, with more images, more moving images, and more interaction with the moving images.

KP: You were reading around this subject because you were interested in the ocean and sea life and then you started grabbing bits as you went? Or were you actively seeking out these stories? Were they stories you had read before and then came back to?

JJ: Nothing that I remember reading before. When they’re in a state of development, I try to make them more interesting to me. And so I was doing research the whole time. I had to read all of Rachel Carson. Three books. I’m working with a marine biologist, and visiting a lot of the footage I shot in aquariums.

KP: Was that your hand interacting with the octopus?

JJ: That was the keeper’s hand. I had my camera so I couldn’t do that, the octopus would’ve grabbed the camera. It was just my iPhone but still, I couldn’t do that.

KP: You spent a lot of time with these creatures.

JJ: Quite a bit. I went to a lot of aquariums.

KP: That performance really felt like a ritual of sorts, to create this kind of communion with the water life. In the way that the surface of the projection screen functioned like the glass of the aquarium, for example.

JJ: It was much more that than anything I’ve ever done. I felt more physically connected with the creatures in the projections than usual.

KP: Interesting.

JJ: This one had an effect on me that I’ve never experienced before. The interaction with the creatures, even though it’s through video. I felt a real closeness. It was very different from what I usually do.

KP: Why do you think that was?

JJ: Because I was looking at the animals and then remembering when I saw the animals and then imagining being immersed by the animals. I think people in the audience felt that way, too, a bit immersed in the animals’ existence, in their world. It was also connected with my research. The books that I have been reading and learning about life in the sea.

KP: It was very immersive. I had dreams afterwards—

JJ: Oh you did?

KP: About my mother swimming underwater. It made me think that some of these mermaid stories are like ghost stories.

JJ: It’s true.

KP: Stories about beings that are on the other side of a divide. All of these stories that you referenced in the performance about mermaids crossing over and having to go back. Even this Uncle Fish story. There are mermaids in Eastern European folklore that were actually believed to be the ghosts or spirits of young women who died tragically.

JJ: Really?

KP: The rusalka.

JJ: Oh, I have to look it up. The rusalka?

KP: Rusalka, yeah.

JJ: It’s like Veselka.

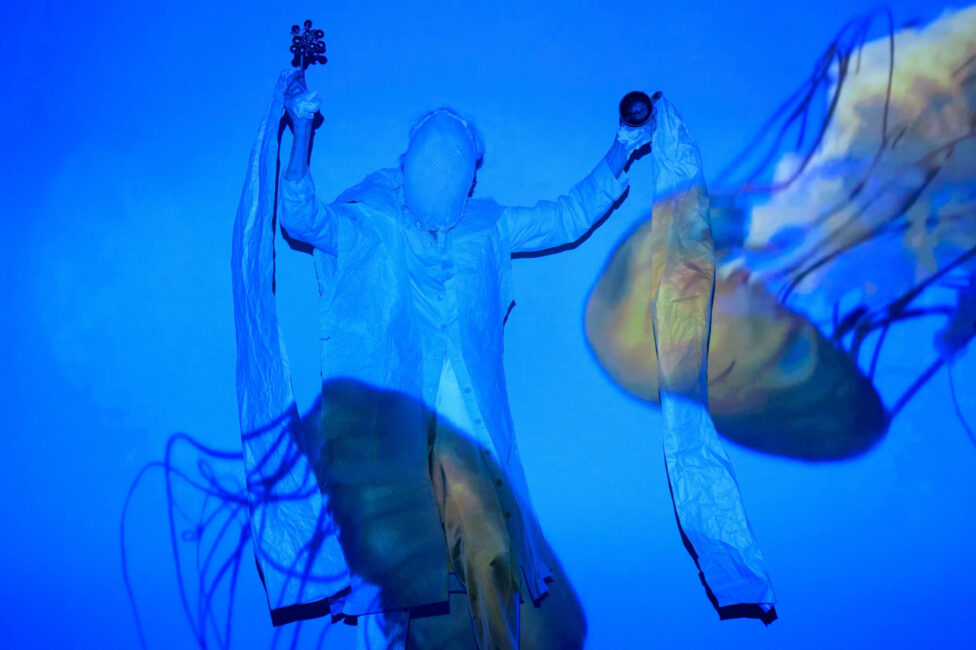

Joan Jonas, Moving Off the Land. Ocean — Sketches and Notes, 2018, Danspace Project, New York. Photo by Ian Douglas. Courtesy Joan Jonas and Gavin Brown’s enterprise, New York / Rome. © 2018 Joan Jonas / Artists Rights Society.

JJ: My very first thought when I started working on this piece was to deal with “How am I going to approach this subject?” The first thought was mythology. The most prevalent myth is of the mermaid. I thought of these animals and creatures who were disappearing as ghosts. That’s amazing about your mother.

KP: In terms of movement, we spoke about drawing, which obviously creates a certain type of movement, but how do you approach the movements and gestures that you use in your work?

JJ: In this case, I moved in relation to the images on the screen. I was trying to interact with the projections by using devices like pieces of paper to magnify certain things. There are actions that have their own movements, like dancing with the seals. My movement always has to do with the relationship to the camera, to the audience, and to the action. The movements are in relation to the very concrete action of making a drawing or working with a prop. And then some of it is just movement. Which also interests me.

KP: We’ve talked before about the influence that the workshops you took in the sixties had on you—workshops with Lucinda Childs, Deborah Hay, Trisha Brown, and Yvonne Rainer. Are there performers, or dancers, or types of performance that you look at now, that you find particularly generative for your own work?

JJ: When you get older, you don’t have so much time to go around and look at things. I love Simone, I always go to see Simone Forti. I can identify with her body movements but I don’t imitate her. I always go to see Yvonne’s work. Frankly, Trisha’s work doesn’t interest me now, if you want to know the truth. It doesn’t relate to my kind of way of working. I admire her a great deal. What she gave was a context for people to do their work. She worked with Viola Spolin and theater games, and then used those as structures in the workshops. And then Deborah Hay. I would go to see more of her work. She’s kind of related to Simone in the fact that she does work that I can more easily enter into.

KP: As a non-dancer, you mean?

JJ: Yeah. The person I like lately is Sarah Michelson. I like it because it’s good.

KP: Even Trisha Brown’s equipment pieces, with the long sticks you find unrelatable? I could see those potentially having been of interest to you.

JJ: Those works were amazing and took strength and courage.

KP: Do you still go see Noh performance when there are opportunities?

JJ: Whenever I can. I go to the Japan Society. And when I go to Japan in November, I’m going to go. I’ll be in Kyoto, so I hope there will be some performances.

KP: What about improvisation? What does that mean to you?

JJ: Improvisation is a natural way of working, sort of developed for everybody. It’s a way of playing with material. Everybody uses improvisation. But I seldom use improvisation in my actual performances. I hope to be able to move through the pieces smoothly without worrying about what I am going to do next, or how I am going to move. That’s my ideal way of performing. It turns into a continual movement, with all the tasks and various things that I have to do. Improvisation is more like play; choosing elements, and choosing how to work with them.

KP: Humor is such an important part of your work. Did you ever try comedy improv? Was that ever something that interested you?

JJ: Throughout my whole life I’ve done silly stupid things for friends and family, generally making a fool of myself. But not publicly. I would never dare do it publicly. But I like to have humor in the work. It’s not something I consciously say, “Oh I’m gonna put some humor here.”

KP: It just comes out naturally.

JJ: Yeah.

Joan Jonas, Moving Off the Land. Ocean — Sketches and Notes, 2018, Danspace Project, New York. Photo by Ian Douglas. Courtesy Joan Jonas and Gavin Brown’s enterprise, New York / Rome. © 2018 Joan Jonas / Artists Rights Society.

KP: I have one more thing to ask you about ritual. I was struck by something I read recently that you said about ritual and performance. That a ritual is for the community and that one of the things that you took from ritual was this idea, the way that simple, repeated gestures could create a connection between the performer and the audience. Do you think a lot about the connection to the audience?

JJ: Well, I think about communicating. I think about the audience being with me. I think about being able to communicate my ideas to the audience. I think about it in that way. How do I communicate my ideas?

KP: Is that still connected to ritual for you?

JJ: I’m using the same methods and ideas, so it is definitely related to ritual, or magic. The word shamanism comes up a lot. I did a lot of research into shamanism. But I don’t consider myself a shaman. It’s just part of the work. Or part of my thinking.

KP: The audience is an important part for you.

JJ: I do it for the audience. I’m doing it for the audience. I don’t do it by myself. I don’t do it to do it by myself.

KP: So you’re not a shaman, but you’re an electronic sorceress?

JJ: I just think that you have to be very special to be a shaman. And it’s a different function, you know, it has a different function.

KP: Do you feel for you that making work right now is very urgent?

JJ: Yeah, sort of.

KP: What gives it urgency to you now?

JJ: My age. But not maybe primarily that. For Moving Off the Land there’s another type of urgency. I’d like to do that piece again because it’s important subject matter. And Time. It’s time. I don’t have time. We’re living in a very weird time. It’s very disturbing.

KP: The subject matter, for people who didn’t see it, being ecological?

JJ: Yes, about the fish, what’s happening to the fish. I mean, most of my audience knows what is happening. So I’m not teaching them anything. But it affects you in some way. How can I really change things? I don’t know. I think it is important for people to know about these creatures, they are so amazing.

KP: And you really emphasize their connection to humans, too.

JJ: Yes, exactly. I don’t think a lot of people are aware. I mean the sea has been this vast, hidden, unconscious thing. We came from the sea.

KP: Is there anything else you want to talk about?

JJ: I can’t think of anything. I might think of something. I can always call you or email you.

KP: Thank you so much.

JJ: Oh you’re welcome, Kristin. It’s a pleasure to do it, and you make me think about certain things. That’s great.

Joan Jonas, Moving Off the Land. Ocean — Sketches and Notes, 2018, Danspace Project, New York. Photo by Ian Douglas. Courtesy Joan Jonas and Gavin Brown’s enterprise, New York / Rome. © 2018 Joan Jonas / Artists Rights Society.