Sean Donovan: I’m Sean Donovan. And I work with you, Jane. I’ve performed and worked as an administrator and sometimes co-director.

Jane Comfort: And you’re responsible for all that video that was in my retrospective, and will be in the documentary.

SD: Yes, and you are?

JC: I’m Jane Comfort.

SD: You just made a retrospective of your forty years making work, but before we talk about the actual event, how does it feel to reach that milestone and realize you’ve been making work for forty years?

JC: It is weird. I think two years ago we realized we were coming on it and we were stunned. ‘Really? Forty? That happened?’ So it is amazing. We had two years to think about this and decide to do this retrospective. And then we were at La MaMa backstage, saying to ourselves “What were we THINKING?” But the amazing magical thing is that nothing went wrong. Everybody came back, everybody was happy to be back. There was so much love. It was sold out, people loved it. It was what we dreamed, but it was crazy what we dreamed.

SD: And the selection of that work was its own process. Because mostly your pieces are evening length, so you had to put together excerpts, right?

JC: I worried that the evening would be a bunch of bonbons because the longest excerpt we did was fifteen minutes. The most requested piece was the Anita Hill/Clarence Thomas section from S/He. Somebody else suggested that I do the pregnancy film For The Spider Woman. I was surprised. I hadn’t seen it in decades. But I watched it again and thought, “Oh my God…”

SD: That was one of your first pieces.

JC: It was from my second concert. At that point I was three months pregnant, and I had decided privately that I would do a one minute improv each month for myself in my new body—whatever the body was that month. Just for me. I included the one minute at the end of the concert I did in Kiva, and nobody knew I was pregnant. A filmmaker friend, Neelon Crawford, came up afterward and said “Oh I love that last piece, I love how wild you were.” I told him the idea and he said “Why don’t we make a film?” I got bigger and bigger and slower until finally I did the last section with this little baby in my arms. I was going through quite a lot and wondering if I could be an artist and also a mom. Would those two things go together? In my very first piece, Steady Shift, which I did the year before, I repeatedly touched parts of my body as I shifted my weight back and forth between a wide second position. I thought it was a very minimal abstract piece, but I realized years later that this touching was a reassuring to myself that I would still be here as an artist if I became a mother.

SD: People found it to be a political act almost, or a social commentary at least.

JC: I hadn’t thought about it as a social commentary so much. Plus I hadn’t seen the film in so long.

SD: It was beautiful to watch it while editing. As a dancer, I was intrigued by watching the way that you had to renegotiate your center, your weight, and yet at the same time, your fundamental technique remained the same. Your line seemed to always extend the same way, but the center was getting wider.

JC: One thing pregnancy does is to make your ligaments pretty loose. That was sort of a gift from pregnancy. It was beautiful to start La MaMa with that.

SD: Not only for your career but for your family, and your life.

JC: The kids would come home from school and they would be a part of rehearsal life. They were friends with people in the company, it was so intermeshed. The early days were so “do it yourself.”

SD: I’m around the same age as you were when you first start making your own performances, and I am beginning the journey of making my own work. It is very “do it yourself” because you don’t have a funding structure yet. When you first started making work, the city was almost bankrupt, there were empty spaces, it was cheap and making work was less professionalized. Maybe you could talk about how making dance has changed for you, and not just for you, but also how you see it having changed for the city, for artists in the city.

JC: I forgot that the city was nearly bankrupt then. But for art making it was so easy. SoHo, Tribeca, The East Village—people had lofts. That was what we did in the late seventies. You might be freelancing for a lot of people or be in a company, and you would just go rent a space and mess around and make something and show it. Today that’s almost unheard of, right?

SD: Now I think one of the problems is that it takes so much effort, funding, and infrastructure to get a show that as an artist you feel a great deal of pressure to do it right. There’s still a great deal of incredible experimentation going on, but it does sometimes feel like you are less capable of quickly trying something out because the effort to make it happen is much greater.

JC: And don’t you think reviews come quicker now because of online reviewing? And that could hurt you. The Soho Weekly News showed up at my second concert and luckily liked what I was doing. I had text in the work and I was doing gesture which became a lifelong thing with me. But the review questioned why someone like me, a postmodernist, would be dealing with meaning, because wasn’t that what postmodernism was trying to get away from? I was starting to break free of those categories. Whereas, now, if you did something that broke wherever you came from, would that be a huge consequence for you? I don’t know.

SD: It’s hard to say. In some ways I think we’re stuck in these categories that weigh us down. I’m struggling to figure out how to market my work, whether it’s dance or theater, and quite frankly I don’t give a shit, I don’t care to categorize it, because it’s not my responsibility.

JC: I’ve talked before about feeling a little bit like an orphan early in the day because I didn’t come out of a huge company. I didn’t come out of a huge studio, but I certainly was downtown in that world and I was freelancing with everybody. And just trying things out. I was a kind of a free floater and when I started using text, I was even more separated. I was doing whatever I was doing. And I was often on my own with that.

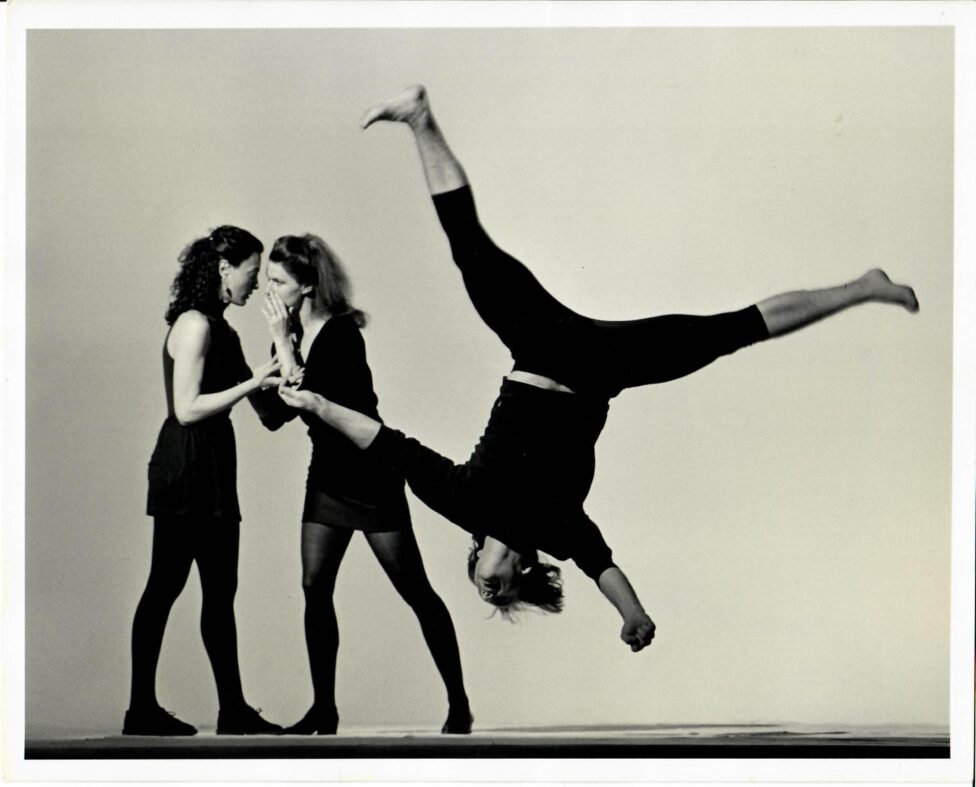

Deportment, 1991, Photo by Arthur Elgort

SD: One of the things I feel like I have continued to be drawn to about your work is that you’ve always been interested in grabbing from many different forms. Sometimes your work is really trying to say something very loud and clear, or dissect a problem or an idea or a way that we look at…

JC: Cultural situations.

SD: You’ve always had the knowledge that if you are trying to say something you will use any means necessary to say it. And if a dance vocabulary wasn’t going to say it loud enough, then you draw from theater, music, installation, an object. That’s why I like working with you. And that’s the way that I envision work too. It sometimes leaves you out of the category of rigor, because you’re not spending all of your energy in these deep movement explorations, like some choreographers are. But on the other hand, you’re making something quite idiosyncratic, because it is this way of working, which is to grab it from everything and then it becomes its own language.

JC: Then you’ve made new art. You’ve broken the walls down and found something new. You’ve made the room bigger. You may be the only one doing it. I mean, think of Judson Church. People were horrified. “What are they doing there? They’re walking around, they’re doing nothing. Dancing with a flag – you’re doing nothing.” In the 80’s, when AIDS struck, postmodernism, or the exercises on six, or an arabesque, were not addressing, and could not address the issue.

SD: Content became important.

JC: So important. Like ACT UP, which became civil disobedience. It became theater in the street.

SD: Pure form was suddenly not going to do it.

JC: It was political. In “Bites”, which took on Newt Gingrich and his Contact with America, dancers had to move back and forth between two rows of chairs, and at the end of each pass sit in a chair, but at each pass a chair was removed by an official. Human behavior ensued. Having chairs removed one by one was the metaphor for the dance. For She/He, I thought “ why don’t I do an evening work reversing the gender of current events?”

SD: This was the piece you made in the mid-nineties, right?

JC: 1995. The piece had a black female President of the United States. It opened with a dancer in my company, Andre Shoals, who was this fabulous drag queen, Afrodite. I went to Diane Torr’s drag king workshop and learned male body language. We opened S/He in drag, then changed to our “proper” genders onstage. I’ve really appreciated knowing male body language ever since. It became clear at one point that I had to do the Clarence Thomas and Anita Hill hearings. We had not only gender reversal, but also race reversal. We got the testimony off CSPAN—all the insulting questions these white senators, including Ted Kennedy and Joe Biden, asked Anita Hill. It was a dog and pony show. They called her a little bit nutty and a little bit slutty. I’m like “Really?” They asked, “Are you in touch with reality on a regular basis, Miss Hill?”

Excerpt from S/He from Jane Comfort and Company’s 40th Anniversary Retrospective, 2018. Photo by Robert Altman (S/He premiered in 1995)

JC: The structural metaphor was to have a senate panel of black females. Anita Hill was a white male, and Clarence Thomas was a white female. We just took the testimony and set it to vocals. When we revised it for the 40th, we were so lucky to have Nancy Alfaro come back as Clarence Thomas. Edisa Weeks, Stephanie McKay and Christina Redd all returned as the Senate panel. Leslie Cuyjet joined them as a newbie, and you as poor Anita Hill, who gets stripped nude and raped, so to speak, before being tossed aside.

SD: When something is restaged, when you’re taking over a role that someone else played, it’s an interesting task. You want to find your own integrity in it. You want to put yourself into it, but at the same time, it has its own rules that you want to try and adhere to. Your own interpretation sometimes is quite small, because you’ve got to follow a structure. And of course I knew that these women who were all in this piece are going to have a memory of the way this person before me did it. One thing that was exciting about being a part of this retrospective was that so many of these people onstage who have come through your company, have then gone on to have major dance careers of their own, many of them great choreographers. That was exciting dance history.

JC: David Neumann and Mark Dendy…

SD: And David Thomson and Edisa Weeks, who are now well known choreographers and practitioners and teachers and scholars of dance. It was exciting to see them together and to work with them. It was a powerful piece to be in because you realize that at the end one of the powers of that piece is that you’ve made the least likely person the victim.

JC: You’re a white male, and you’re the victim.

SD: And that is never the case. So to be stripped bare, it was vulnerable, but also I was proud to be part of giving the audience that kind of perspective.

JC: And the terror.

Amazing Grace from Jane Comfort and Company’s 40th Anniversary Retrospective, 2018, Photo by Maria Baranova

SD: You presented a forty year retrospective and that is a kind of milestone. A look backwards mostly. it’s also a way to start fresh, and I wonder, what do you see as you finish this point now that you’re reaching an older age. What do you want to do?

JC: One of the challenges that I have always given myself over the years is to scare myself, challenge myself with what I didn’t know. In the last couple of pieces the challenge has been to not use text but just space and time, which is basically what traditional choreographers do. I will say it’s just as hard as trying to deal with a narrative. I don’t know what new piece I would make now. We’re living in a horrible time. I have been responding to horrible politicians my whole life, but I don’t know if I want to make a political piece again—well, I did make one—I made Amazing Grace about our president.

SD: Donald Trump.

JC: But I

SD: But we can’t tour the show we did. Too many people.

JC: 25 people. Could we put together an evening of political works, works with social commentary with a smaller cast? That’s what we are trying to do right now.

SD: And then you’re also kind of digging into your archive, right? And trying to make a documentary.

JC: Be careful what you wish for! I’m having to go through many, many piles of history. Good thing to do after forty years. And beyond that, what was so incredible was just bringing back all these company members who had worked with me years ago. Coming back into the loft and recreating their roles. I wasn’t ready for the emotion of that. I didn’t realized that there was going to be so much emotion in revisiting these pieces and all these people coming back in. When we did the rehearsal for Asphalt – the piece I did with Toshi Reagon and Carl Hancock Rux in 2001– oh my god, when that group walked in the space it was fifteen minutes of screaming, running in circles, hugging each other, kissing, crying.

SD: Some of those people hadn’t seen each other in fifteen years.

JC: So much joy for everybody and that was just the most beautiful thing of all. And having you younger company members working in tandem with older company members and having a new person come in to a role. When we would circle up before the show, everybody was smiling so happily at each other, and we were all like “we have to keep this going!” Which is impossible.

SD: It was a rare feeling to have all that positivity and joy.

JC: And I don’t know, for you all, all up in the dressing room, what that was like.

SD: It was exciting to be reminded of how much knowledge is stored in the body. I remember watching some of the performers stepping back into a rehearsal from a piece they did twenty years ago or more. It was stored in there, even the rhythms were in their body. That always amazes me about dancers, the way they store all of that in their body.

JC: And you automatically do it.

Interview has been condensed and edited.

“Three Bagatelles for the Righteous” 1996, photo by: Arthur Elgort