Ishmael Houston-Jones: We are talking about THEM, the reconstruction that was at P.S. New York, and when was the date?

Chris Cochrane: June 2018.

IHJ: It ran for eight performances over two weeks. Jenny Schlenzka, who is the new director, did her first season which highlighted the history of Performance Space. She asked me early on last winter if I would like to revive THEM, a piece that was originally a collaboration with composer Chris Cochrane who’s sitting here with me, and writer Dennis Cooper. We did a work in progress version in 1985, and a full length version in 1986. It was revived again in 2010, and it toured from 2011 to 2014. It toured to the American Realness festival her in New York, as well as the Spring Dance Festival in Utrecht, Netherlands, Pompidou center in Paris, Tanz im August in Berlin, REDCAT Theater in Los Angeles, and TAP in Poitier, France. So when Jenny first approached me I really was hesitant. I had just finished a piece also sort of rooted in the 1980s, variations on themes from Lost and Found and other works by John Bernd. I was wondering why if I really wanted to do something as a revival again or based in the 1980s. And Dennis who has relocated to Paris, France was also hesitant because it means that he would have to travel here. Chris how did you feel about doing the revival?

CC: I was actually thrilled to be asked. It’s just a piece of work that I feel very inside of. And anytime we’ve brought it back there’s been a resonance. So I was maybe not skeptical, I was excited to see what we could bring to it this time. I think when we had the auditions then I might have become skeptical a little bit, but we can talk about that later.

IHJ: It’s interesting you say that because it was at the audition that I actually got more excited about it. Seeing a new generation of young male dancers in the room and, I also thought that I was a better director this time around. I felt like we had a larger pool of people to choose from. I think 45 people or so came to the audition. It was interesting to actually go through really see specifically what we were looking for. I got excited about some of the people who auditioned and I thought we got a really good group.

CC: We got a good group, and want to mirror what you said. You were a better director. There was a clarity that you brought, and when we finally brought the dancers together at first they weren’t per say “getting it,” or being intimate with one another. And you did a couple of exercises that really transformed how they interacted. They were really simple, but so helpful. Can I talk about one of them?

IHJ: Sure!

CC: One that was really incredible to me – Ish had them couple up and one of them closed their eyes and the other held their hands and they walked around the room, and the one who had their eyes closed talked about a sexual experience they had to the person leading them around the room. And just to listen to them do that and how honest they were with one another about these sexual experiences. I think that as a directorial idea about being intimate with one another was very different from previous versions we had done, and to do that early on allowed the dancers to be comfortable with one another.

IHJ: Yeah that memory is really strong for me, how things shifted – the other big shift, is the time shift, because there was this 25 year gap between when the piece was made and several of the dancers weren’t born when the piece was made in 1986, and talking about gay life and AIDS, even dancers who identify as queer or gay in the piece had a hard time grasping exactly what that meant. Especially for Dennis’ writing, which weaves in and out of the piece. We spent a lot of time really trying to explore giving them an idea of what that felt like– probably an equal amount of time than with the dancing and moving exercises that we did. I had just worked on this piece that was about the choreographer John Bernd who died of AIDS in 1988, and two of the dancers in THEM were in that piece as well. I had video documents of his work from the 1980s, and there was a progression, that piece dealt with the last seven years of his life. He starts off in 1981 being a robust, healthy, beautiful dancer and by 1988, six months before he died, he’s doing this duet with the dancer choreographer Jennifer Monson where he weighs about 100 pounds and is obviously just dislocated in his own piece, like he can’t, and she’s helping him get through the piece. And I showed them large chunks of those pieces. To give them an idea of that time, that many of our friends died, as John did. The piece isn’t about AIDS, AIDS is never mentioned by name in the piece, but it does inform the time when the piece was made.

CC: And there’s a scene of the dance where a dancer is being throw back and forth, and up until you showed that segment of John, it was sort of rote, very stiff. And after you showed the videos of John that section all of a sudden changed dramatically.

IHJ: Right, very much.

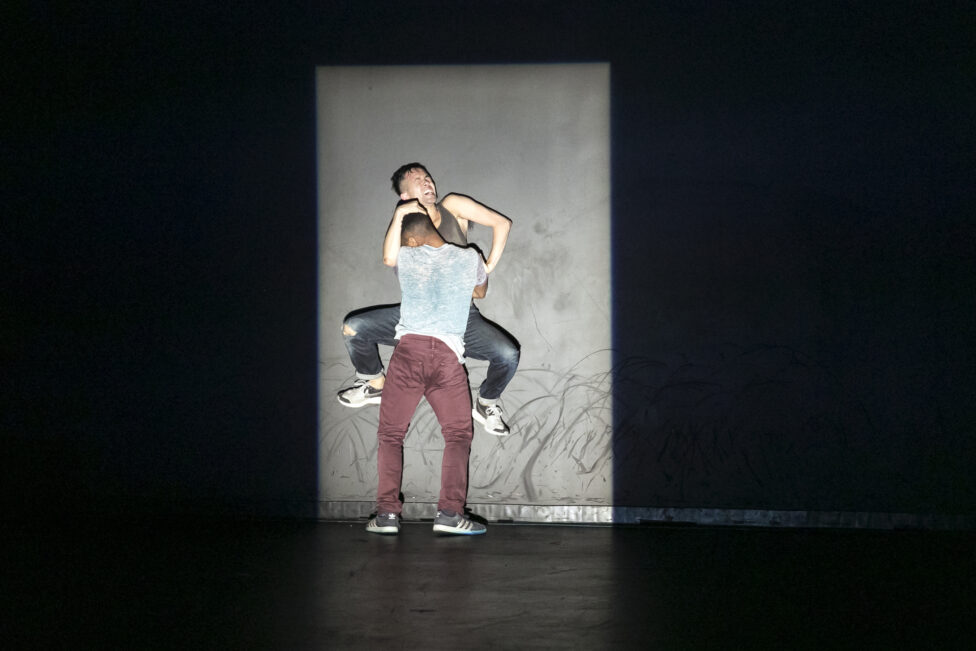

Johnnie Cruise Mercer, Hentyle Yapp in THEM at Performance Space New York, 2018. Photo by Rachel Papo

CC: At some point one of the dancers was doing the cruising scene. He asked a great question “Well am I supposed to re-enact this, or am I doing this as me?” And yes, to allow this person to bring his own experience to this thing we were trying to convey to him. The structure of Dennis’ writing, which is mostly about growing up in California, experiences of intimacy or lack of intimacy with guys and Ish’s instructions of dance and my music and letting them try to inhabit and bring their own story to it. This time I felt less encumbered by the AIDS narrative. It felt much more about relationships. The relationships with men and how they work and don’t work. Interruption, how things can fall apart, how things can be together.

IHJ: That’s true, relationships are fucked. They’re hard, and they don’t work and there’s always disharmony, and one of the dancers suggested that cuddling exercise. We were trying to get this sense of things not working. There’s a tendency in dance for things to work, especially in improv. And actually it’s always very counterintuitive to make things not work. And the image was given, like when you’re lying in bed with someone you’re intimate with and you’re both trying to sleep and at first it’s really comfortable and somebody moves an arm and the whole thing falls apart. And we actually had them do that. To pair up and lay as if they were sleeping together, but one person always making the other person uncomfortable. That you’re trying together, trying to make things work. You’re trying to lift, you’re trying to lean, you’re trying to support but the support disappears from underneath you. And that’s a metaphor for not even gay relationships, sort of a universal failure of relationships. Trying; like you’re trying to keep things together, but having it fail. The AIDS thing came when we did the full length version. Chris, Dennis and I felt that because of what was happening in our personal lives with our friends and lovers, and colleagues and strangers all around us, that we couldn’t do a piece that was about men, and largely queerish-identified men without having any reference to AIDS, so we added a coda that dealt with that. But it’s not dealt with in the language, it’s dealt with in the dance.

CC: The piece has had this trajectory, a sort of a legacy, so even though it’s about many things, it has this way of being about HIV and AIDS. It’s in the room, it just is in the room. My therapist came and it’s the first time I had invited her to anything. And she remarked about how young most of the audience was, and what was their experience of seeing this? I would be interested to know how young people felt. How are they witnessing it?

IHJ: Right. And one of my former students from Sarah Lawrence, who’s probably either in his late twenties or early thirties was weeping. Which is interesting because he was not around during that time, at all. He wasn’t born during that time.

CC: I work for a community service organization that services people with HIV and AIDS, and a coworker came and when I saw him the next day he embraced me and said, “Thank you for telling my brother’s story.”

IHJ: Wow.

Ismael Houston-Jones, Kensaku Shinohara and Jeremy Pheiffer in THEM at Performance Space New York, 2018. Photo by Rachel Papo

CC: He was appreciative that there was something that was conveyed in the piece that was very genuine and real. Relationships and how maybe the ramification or lack of ramification. How things fail, how things fall apart. There is also the scene of dancing with a dead goat. To me that’s pretty significant about dancing with death and dancing with devil or something.

IHJ: I added that in the 1986 version as part of the AIDS coda. I had this very tangible fear of death because friends like my friend John Bernd and many others were sick and I was going to the hospital a lot and I was going to memorial services. I needed to cathartically deal with that. I’m also really squeamish about dead mice, bugs, you know. Squeamish about death in general and dead things and dead bodies. And I had this image, using Christian mythology of goat versus lamb, I felt that AIDS was this satanic thing but also this seductive thing. You’re trying to get rid of it, you’re trying to throw it away, but it just keeps coming back and you’re trying to make love to it and you’re trying to wrestle with it and you’re trying to kill it and it’s all of like fifty seconds.

CC: It’s not long.

IHJ: And then in the very final scene, there is a dance based on touching lymph nodes. On either side of the neck, the armpits and in the groin. And dancers are visualizing looking in a mirror, and checking themselves. Chris did a lot of good explanation of what that is, like what that was. As I remember it, you sort of catch a cold and then suddenly you wonder if you’re going to be around in six months. And then most of the dancers are wrestled to the ground by Jeremy Pheiffer, who’s the death figure.

CC: The first time we did it in 1985, all the music was improvised. And I really wanted to keep that as part of it, but as the piece has become more codified in the 2010-2014 version, the idea was that I wanted to layer some history, some cassette recordings that were from the past, and layer something on top of it. There’s these moments where there are drones going on, kind of as ghosts that are inhabiting the piece. So, there’s this archival material that’s built upon that then I improvised over. For the end I made a very long loop of these kids playing. In the 86 version was just the playground sounds while the lymph nodes was happening. I’ve played guitar over the top. The sound system was much much better this time, the guitar was much more aggressive, still keening, but much louder. And I remember Ish said, “Oh but you shouldn’t get it so loud there, it’s not so dramatic.” I’m like wanting to make it overly dramatic but being told not to. It’s a weird tension. Here are these adult men feeling their lymph nodes and you have this playground scene underneath, it’s very innocent, right? A memory of being kids, but here we are in this adult world. Dennis’ is about remembering and not wanting to remember and tearing up a picture. All of these elements are randomly put together and ti becomes this really strong ending. The other thing I find provocative or interesting about using that recording of the playground at the end of the piece, is that all the kids recorded in the playground have grown up or died by now, or could even have been dancers in the piece or have encountered the various scenarios that THEM suggests/ depicts. It’s actual snapshot of the time the piece was originally made that we are listening to. We continue to bring this snapshot forward each time we reconstruct THEM. The music that overlays it gets louder and more distorted each time, as well. Make of that what you will.

IHJ: It’s really strong, and that points to another thing that seduced me into wanting to do it again. Is that that space, that new space, the technology in this new theater at Performance Space New York is incredible. It’s intimate. The audience is right there with us, that sort of won me over to think “Oh, it’ll be really interesting to do it in this new space. This new place.”

CC: And also when Dennis came, I felt the skepticism in the room. But there was an energy that the dancers were conveying after these exercises around intimacy, and Dennis really engaged, like “Oh well there is something here.”

IHJ: So, the dancers in the piece are Alvaro Gonzalez Dupuy, Michael Watkiss, Johnnie Cruise Mercer, Michael Parmelee, Hentyle Yapp, Jeremy Pheiffer, and Kensaku Shinohara.

CC: One more thing. Johnny had to do this solo dance, if you will. There are two couples that are dancing in circles of light.

IHJ: Very tight, small circles. It’s always choreographed that two couples would be doing their dance, and he would come out and they would just leave. And Johnny Mercer, he didn’t know what to do. The dancers almost never left the stage, they were always off to the side, there was no off place. So, he said; “what do I do while I’m waiting?” He decided to enter the space to look and just go from one couple ot the other and just look as the outsider.

CC: And he talked about it, that when he was doing the dance it was not a linear thing, that there were many things going on at the time. How do you inhabit all of these contradictory feelings at once? There’s a great line from John Coltrane “I start in the middle of the sentence and I go in both directions.” And in some ways it’s what Johnny was talking about. He wasn’t trying to linearly inhabit, he was trying to expand in both directions. It’s a really interesting idea musically, too. It’s like, stop thinking of the sections and then find your own narrative throughout the piece. You have Dennis’ text, you have Ishmael’s direction and choreography and my music, and how are you inhabiting this piece? Are you just paying attention to the music? Are you just paying attention to the language? Paying attention to the choreography? What’s your narrative that you can find through this? And not dictating that. Just saying that each one of you should find narrative to it.

Interview has been condensed and edited.

Jeremy Pheiffer and Michael Watkiss in THEM at Performance Space New York, 2018. Photo by Rachel Papo