preface to a manifesto of persistence

As a vital conduit of free expression, dance and the performing arts have long intervened in contentious social and political moments. Today, conservative political campaigns to revert advancements in diversity, equity, education, and healthcare policy; nationwide violations of free speech; and the recent election of a convicted felon leave many anxious about what is to come. This moment encourages the Movement Research Performance Journal Editorial Intern Team to investigate how contributing artists of the Journal’s past have both responded to and persisted through transitional political times.

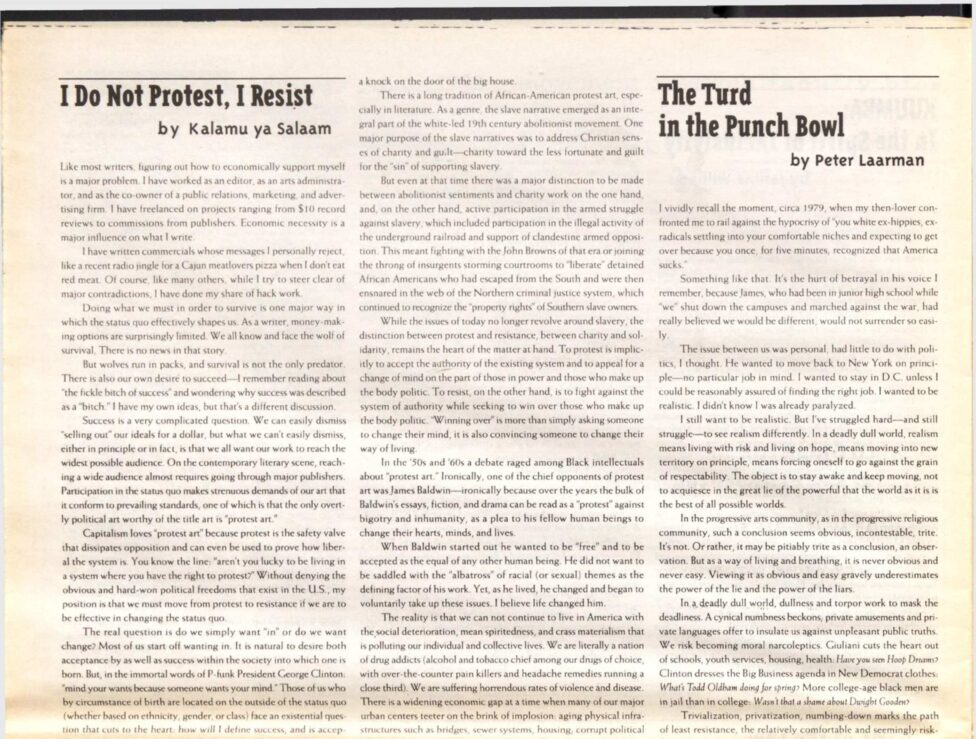

In the forthcoming weeks, our team will publish a compendium on mrpj.org entitled a manifesto of persistence. This curated selection of articles from the archive of the Movement Research Performance Journal invites readers to engage an empowering legacy of interpersonal, organizational, pedagogical, and performance practices for persisting through troubled times—however transitional or interminable. This week, we offer a preface to this project. Kalamu ya Salaam’s 1995 article “I Do Not Protest, I Resist” is the first of several articles we will recirculate in the coming weeks.

— Storm Stokes, MRPJ Intern

Kalamu ya Salaam’s “I Do Not Protest, I Resist” examines the “status-quo” and “success” from the lens of being an artist in the united states. Salaam critiques “protest art” and instead advocates for “resistance art” as an integral artistic and socio-political tool. although published in the Movement Research Performance Journal in 1995, Salaam’s article felt like it could have been published yesterday, today, next week, or [insert future time here]. “I Do Not Protest, I Resist” serves as a glaring, somewhat painful, deeply enraging reminder that history is cyclical, or rather, that the root of the conditions for working artists from the past thirty years have not changed all that much. if anything, the same structural conditions of class imbalances and inequity in the field have become even more pervasive. this is not to discount the changes that have been made and the fights that have been won, but is to say what we’re seeing and experiencing now as artists in 2024 is not new or surprising; artists are still playing and fighting to survive in the game of late stage capitalism and ever-present white supremacy that conditions how funding, notoriety and success operate. Salaam brings forth a quandary that I find myself and fellow working-class artists navigating and discussing as we make and participate (or choose not to participate) in this work:

My position is simple. We live in a period of transition. We can protest the current conditions and/or we can struggle to envision and create alternatives. We can plead for relief or we can work to inspire and incite our fellow citizens to resist. As artists, we have a choice to make. Indeed, there is always a choice to make.

— mik phillips, MRPJ Intern

The MRPJ Editorial Internship Team: Spencer Klink, Ethan Luk, mik phillips, Chloe A. Schafer, Storm Stokes, Cameron Surh

"I Do Not Protest, I Resist" by Kamalu ya Salaam, 1995

Like most writers, figuring out how to economically support myself is a major problem. I have worked as an editor, as an arts administrator, and as the co-owner of a public relations, marketing, and advertising firm. I have freelanced on projects ranging from $10 record reviews to commissions from publishers. Economic necessity is a major influence on what I write.

I have written commercials whose messages I personally reject, like a recent radio jingle for a Cajun meatlovers pizza when I don’t eat red meat. Of course, like many others, while I try to steer clear of major contradictions, I have done my share of hack work.

Doing what we must in order to survive is one major way in which the status quo effectively shapes us. As a writer, money-making options are surprisingly limited. We all know and face the wolf of survival. There is no news in that story.

But wolves run in packs, and survival is not the only predator. There is also our own desire to succeed—I remember reading about “the fickle bitch of success” and wondering why success was described as a “bitch.” I have my own ideas, but that’s a different discussion.

Success is a very complicated question. We can easily dismiss “selling out” our ideals for a dollar, but what we can’t easily dismiss, either in principle or in fact, is that we all want our work to reach the widest possible audience. On the contemporary literary scene, reaching a wide audience almost requires going through major publishers. Participation in the status quo makes strenuous demands of our art that it conform to prevailing standards, one of which is that the only overtly political art worthy of the title art is “protest art.”

Capitalism loves “protest art” because protest is the safety valve that dissipates opposition and can even be used to prove how liberal the system is. You know the line: “aren’t you lucky to be living in a system where you have the right to protest?” Without denying the obvious and hard-won political freedoms that exist in the U.S., my position is that we must move from protest to resistance if we are to be effective in changing the status quo.

The real question is do we simply want “in” or do we want change? Most of us start off wanting in. It is natural to desire both acceptance by as well as success within the society into which one is born. But, in the immortal words of P-funk President George Clinton: “mind your wants because someone wants your mind.” Those of us who by circumstance of birth are located on the outside of the status quo (whether based on ethnicity, gender, or class) face an existential question that cuts to the heart: how will I define success, and is acceptance by the status quo part of what I want in life?

While it is simple enough to answer in the abstract, in truth, i.e. the day to day living that we do, it’s awfully lonely on the outside, psychologically taxing, and ultimately a very difficult position to maintain. Who wants to be marginalized as an artist and known to only a handful of people? Given the choice between having a book published by a mainstream publisher and not having one published by a mainstream publisher, most writers (regardless of identity) would choose to be published, especially when it seems that one is writing whatever it is one wants to write.

Without ever having to censor you formally—after a few years of rejection slips most writers will censor and change themselves—mainstream publishers shape contemporary literature by applying two criteria: 1. is it commercial? or 2. is it artistically important? Either will get you published at least once, although only the former will get you published twice, thrice, and so forth.

Unless one is very, very clear about one’s commitment to socially relevant writing, even the most revolutionary writer can become embittered after 30 or 40 years of toiling in obscurity. As a 47-year-old African-American writer, I know that if you do not publish with establishment publishers, be they commercial, academic, or small independents, then you will have very little chance of achieving “success” as a writer.

I sat on an NEA panel considering audience development applications. One grant listed Haki Madhubuti as one of the poets an organization wanted to present. I was the only person there who knew Madhubuti’s work. I was expected to be conversant with the work of contemporary writers across the board. But how is it that a contemporary African-American poet with over one million books in print, who is also the head of Third World Press, one of this country’s oldest Black publishing companies, was unknown to my colleagues? The answer is simple: Madhubuti is not published by the status quo. He started off self-publishing, came of age in the ’60s/70s Black Arts Movement, and is one of the most widely read poets among African Americans, but all of his books have been published by small, independent Black publishers.

Too often success is measured by acceptance within the status quo rather than by the quality of one’s literary work. That is why we witness authors proclaimed as “major Black writers” when they have only published one or two books (albeit with major publishers) within a five-year period. There is no surprise here. My assumption is that as long as the big house stands, “success” will continue to be measured by whether one gets to sleep in big-house beds.

This brings me to the subject of protest art. The reason I do not believe in protest art is because I have no desire to bed down with the status quo nor do I have a desire to be legitimized by the status quo. Instead, my struggle is to change the status quo. For me protest art is not an option precisely because in reality protest art is simply a knock on the door of the big house.

There is a long tradition of African-American protest art, especially in literature. As a genre, the slave narrative emerged as an integral part of the white-led 19th century abolitionist movement. One major purpose of the slave narratives was to address Christian senses of charity and guilt—charity toward the less fortunate and guilt for the “sin” of supporting slavery.

But even at that time there was a major distinction to be made between abolitionist sentiments and charity work on the one hand, and, on the other hand, active participation in the armed struggle against slavery, which included participation in the illegal activity of the underground railroad and support of clandestine armed opposition. This meant fighting with the John Browns of that era or joining the throng of insurgents storming courtrooms to “liberate” detained African Americans who had escaped from the South and were then ensnared in the web of the Northern criminal justice system, which continued to recognize the “property rights” of Southern slave owners.

While the issues of today no longer revolve around slavery, the distinction between protest and resistance, between charity and solidarity, remains the heart of the matter at hand. To protest is implicitly to accept the authority of the existing system and to appeal for a change of mind on the part of those in power and those who make up the body politic. To resist, on the other hand, is to fight against the system of authority while seeking to win over those who make up the body politic. “Winning over” is more than simply asking someone to change their mind, it is also convincing someone to change their way of living.

In the ’50s and ’60s a debate raged among Black intellectuals about “protest art.” Ironically, one of the chief opponents of protest art was James Baldwin—ironically because over the years the bulk of Baldwin’s essays, fiction, and drama can be read as a “protest” against bigotry and inhumanity, as a plea to his fellow human beings to change their hearts, minds, and lives.

When Baldwin started out he wanted to be “free” and to be accepted as the equal of any other human being. He did not want to be saddled with the “albatross” of racial (or sexual) themes as the defining factor of his work. Yet, as he lived, he changed and began to voluntarily take up these issues. I believe life changed him.

The reality is that we can not continue to live in America with the social deterioration, mean spiritedness, and crass materialism that is polluting our individual and collective lives. We are literally a nation of drug addicts (alcohol and tobacco chief among our drugs of choice, with over-the-counter pain killers and headache remedies running a close third). We are suffering horrendous rates of violence and disease. There is a widening economic gap at a time when many of our major urban centers teeter on the brink of implosion: aging physical infrastructures such as bridges, sewer systems, housing, corrupt political administrations, and increasing ethnic conflict. Something has got to give.

My position is simple. We live in a period of transition. We can protest the current conditions and/or we can struggle to envision and create alternatives. We can plead for relief or we can work to inspire and incite our fellow citizens to resist. As artists, we have a choice to make. Indeed, there is always a choice to make.

Protest art always ends up being trendy precisely because the art necessarily struggles to be accepted by the very people the art should oppose. Ultimately, protest artists are, by definition, more interested in relating to the enemy than relating to the potential insurgents. This is why we have protest artists whose cutting-edge work is rejected by neighborhood people.

Yes, neighborhood people have tastes that have been shaped by the consumer society. Yes, neighborhood people are parochial and not very deep intellectually. Yes, neighborhood people are unsophisticated when it comes to the arts. But the very purpose of resistance art is to confront and change these negative yeses! Our job as committed artists is to raise consciousness by starting where our neighborhoods are, and moving up from there.

Resistance art needs to be internalized by an audience of sufferers in order to be successful. The horrible truth is that every successful social struggle requires immense sacrifices, and the committed artist must also sacrifice — not simply suffer temporary poverty until one is discovered by the status quo, but sacrifice the potential wealth associated with a status quo career to work in solidarity with those who too often are born, live, struggle, and die in anonymous poverty.

We think nothing of the millions of people in this society who live and die without ever achieving even one tenth of the material wealth that many of us take for granted. We think nothing of those who are literally maimed and deformed as a result of the military and economic war waged against peoples in far-away lands in order to insure profit for U.S.-based billionaires. Somehow, while the vast majority of our fellow citizens are never recognized by name, we artists think it ignoble to live and die without being lauded in the New York Times.

But if we remember nothing else, we should remember this. Ultimately, the true “nobility of our humanity” will be judged not by the status quo but by the people of the future—the people who will look back on our age and wonder what in the world could we have had on our minds. Protest is not enough, we must resist.