Gabrielle Civil:

Okay, here we are. We made it. So, what’s been going on?

Steffani Jemison:

Oh, not much—the typical mid-semester wildness. And I published a book, so that has added another layer of complexity to my autumn, but has also been such a joy.

GC: Congratulations!

SJ: Thank you.

GC: How does it feel to have that book out in the world?

SJ: You know, I didn’t expect it to feel any different from having any other work of art out in the world. I was wrong. It turns out, it’s totally different.

For one thing, my community of practice has often been able to access my art objects in a way that I think of as passive. If you have work in a gallery or museum, it’s not too difficult for someone to stop by, even briefly. It feels like a much bigger and more meaningful—at least to me—investment or signal of intention for someone to go out, or go online, place an order, bring something into their home, and then spend time reading it, working through it.

Also, the book is so intimate. Yes, it’s fiction, but it still feels very much like the product of my mind and body in a weird, personal, sticky, material way. Almost in a gross way. Like, other people now have to deal with this thing I made. In my writing group, I talked about this intimacy in the form of bodily excretions—ha!—but I could just easily frame it more affirmatively. Like when you cook something for someone and then they have to contend with it. Cut it up, tear it apart, savor it, swallow it, spit it out, they can be blissful about it or repulsed by it, etc.

GC: I hear you. One time I was wearing something that I would say was lined or checked or a little herringboned . . . And someone I didn’t know very well said to me, What are you wearing that for? You don’t like plaids. And it’s true. I had to wear uniform skirts for many, many years of my life so now I don’t ever want to wear a plaid again. But I was like, How do you know that? Just the fact that I had written that kind of detail about myself and someone picked that up—that kind of knowing is pretty amazing. It shows a kind of close-reading that I experience as a gift.

So I’m just thinking about intimacy and the personal, or how intimacy can be created just through close attention. We’re in this moment where there’s a lot of self-disclosure, a lot of personal sharing that, for me, doesn’t always create a feeling of intimacy. But I’m recognizing, as a person involved in a lot of life writing, both on the page and in performance, that it can be such an intimate mode, and maybe that’s partly why I do it.

SJ: It’s interesting, the phrase “life writing” and what it means to think about writing as a tool that almost covers the life, like a cloak or a glaze, protecting and mediating and revealing life at the same time.

One thing I didn’t expect is that, although the book I wrote is titled A rock, A river, A street: a novella, and is framed consistently as fictional, because the narrator has some biographical features in common with me, many readers think that the narrator is me. They think that I wrote a confession, essentially, of why I am the way that I am. I mean, thank goodness everything that has happened to my narrator didn’t happen to me in real life. That said, of course, I drew from tidbits and details of what I know, and there’s definitely a plaid uniform skirt in the book. [laughs]

As a Black kid—one of very few Black kids in my Catholic schools and private schools growing up—I was always super aware of the way that no uniform could produce uniformity in the relation between my body and the bodies of my white classmates, and I became incredibly attentive to the details that differentiated one person’s ankles from another person’s ankles, one person’s knees from another person’s knees. That observation did make its way into the novel, but most of it is actually fictional.

I would love to talk more about the way that you navigate multiple creative communities. So much of my creative world is situated in the visual arts as a discourse and genealogy—with occasional excursions into music and performance and writing. I have learned that many of the artists and critics and curators and art enthusiasts I know don’t read fiction. They are very confused about my choice to write fiction, and have so many questions about how to even engage with the text. They wish it were autobiographical, indexically connected to my own life, which would inscribe the work within a more comfortable and familiar relationship between text and image: text as a caption or as a key or a codex, a matrix that enables you to decode some other aspect of the world. But as fiction, they’re very confused.

GC: That is so funny and resonates with some conversations that I’ve had, or some quizzical responses. There’s this word in French that I love, “décalage,” which is a lag or split. And for me that describes how the time of the writer and the time of the reader are so different. Time has an accordion quality. The time when I first have an idea, the time when I first do something in the studio, the time when I first write something on a page, the time when something is maybe shared with someone else—that accumulation of time feels really important.

So when people are looking at one of your sculptures, when they’re coming to one of my performances, when they are reading our books and maybe they’re spending two minutes on it, but maybe it was five years that we’ve spent on it. [laughs]

SJ: Such a beautiful observation. I absolutely reflect on those distinctions, the multiple experiences of time that interact in a single work. It’s often the case, in my practice, as in yours, that a concept or an idea will unfold in multiple ways over time, maybe in different media, sometimes even reflected or relayed across different beings. It’s also the case that my video, sound, and kinetic sculptures are durational, sometimes evoking experiences of time that extend far beyond any viewer’s capacity to sit or to witness.

This compulsion to return again and again to the same material served as the point of origin for my book, which, while it is not about pantomime, per se, certainly takes up some of the physical problems that I began to think through very deeply with my collaborator—the actor Garrett Gray—who served as the physical performer in our collaborative performance “On Similitude” (2019) as well as my video, Similitude (2019). That compulsion to return haunts my daily life, too. I really enjoy doing things exactly the same way.

One of my closest friends, who’s also a writer, and I share a hobby. And we really like it when each time is exactly—EXACTLY—the same. We prefer to be able to ease into not just a similar experience but a virtually identical session, week after week. Another example: I’ve taken dance classes with a number of instructors trained by Lynn Simonson. One reason I enjoy Simonson Technique classes is that they share the exact same introduction; it never changes at all. It’s easier to track changes within me because the compass is always pointing in the same direction.

[ID: A video still depicts a man stretching his mouth open wide as he looks into a mirror. Video still: Steffani Jemison, Similitude (2019). Courtesy of the artist, Greene Naftali, NY, and Annet Gelink, NL.]

GC: That sameness was a big part of my last book, the déjà vu. There’s so much about repetition in there. Although, in the déjà vu, repetition implies some kind of ghostliness, and it is really about tracking changes and tracking what doesn’t change as well; thinking about how things repeat over time, and how that repetition could be individual and collective, or how we could share a body that’s repeating through history or time. That feels really exciting to me. And what you said reminds me of how the beginning of a ballet class is usually the same, as well as the beginning of a lot of yoga classes, so there are certain physical practices to ground you. It feels so good to return. I wanted to ask you, what drew you to fiction as a mode?

SJ: It’s such a good question. My work has had so much to do with the activities of formation and being formed—not form as shape, but rather activities of shaping, and the ways that we are shaped. When I was invited to make this book, I saw an opportunity to engage with bookmaking directly, and fiction was a received form I was curious to try working within, to see what was possible.

I was aware of the triangulation that would inevitably unfold between my voice and the voice of the narrator and questions of, I’ll say, belatedness and anticipation. One of the reasons that I have returned to pantomime, thematically, is because it forces me to think about this question of what it means to come after, which for me is a big existential question that I share with some of my peers. My work is shaped by traditions that I deeply honor—my work sometimes takes the form of honoring and holding those traditions—and yet I have an ambivalent and complicated relationship to framing my practice in relation to the past. How can we carry something that we’ve learned and also open ourselves to what’s next? There’s something that’s uniquely complex about that heavy role, that kind of being open in two directions at the same time, that feels just generational. I think we’re of a similar age, similar generation. I don’t know if you’ve ever felt that.

GC: Oh, you just said that so beautifully. I’m a few years older than you, but I definitely feel what you’re saying. At the same time, in my heart, I still feel so wide-eyed and new. I feel like the original ingénue where everybody took the class that I didn’t take, or everybody knows the thing that I don’t know. You know what I mean? And that’s part of what I’m interested in doing in art-making, in writing: I’m trying to learn, trying to discover, trying to…because I don’t think I already know. I feel like we’re living in a moment where everybody not only knows everything, but everybody is sure that they know everything and they want to tell you. And as a teacher, I’ve been struck not just by how some people are arriving with their certainties, and the impact of that, but how other people are arriving, or sometimes even the same people, just completely shut down. They might say: I could never talk about such and such. And I feel very troubled because I don’t know what has happened to curiosity, or what has happened to witness, or what has happened to being able to make a mistake.

[ID: In dimmed light, Gabrielle, wearing a black dress, tights, and silver boots, dances. Her knees are bent, one arm is raised and the other swings behind. Gabrielle Civil, Q & A. Photograph by Ally Almore. Courtesy of the artist.]

SJ: Sometimes I feel the same way that you do—that students in my classrooms aren’t as curious, or as willing to take risks, as I would hope. But other times, it’s clear that the issue isn’t that young people are less curious, but rather that the university system is not a place where anyone can be their best selves, students included. Because when I look at the world and especially the art worlds I inhabit, and when I look at challenges that young people are bringing around the repatriation of artifacts from the Met, challenging the structure of Boards of Directors and Boards of Trustees, challenging hierarchy in the workplace and the expectation that they will work long hours for no pay, challenging unpaid internships, challenging so much of what I simply accepted as a fact of life, I see that they are clear, focused, and can call it like it is. When they don’t bring that same energy to my classes, I wonder whether it’s the university system rather than the students that are failing to be creative. I mean, look at me. I know for a fact that the university is not getting the very best of me. That’s not to say I don’t work hard; it’s just a fact that the most spirited, creative, smartest version of myself is not produced by a world of learning outcomes and diversity committees and faculty meetings. The most impactful Steffani is not capable of being squeezed into that container. That must be the case for students as well.

GC: I love that you said that so much. And I just chuckled because it made me think about some recent meetings at work where I have just been like, Okay, is that really how you all want to do that? Or just feeling like there could be some other much more creative way, much more interesting thing that we could do together. This is my what? 22nd year of being a professor? And so I’ve had to reckon with some big changes. In society, people don’t seem to believe in schools as a place of transformation anymore—unless they are schools that they create themselves. Charter schools or new educational programs. I struggle with that because I was completely transformed and nourished and supported by school, even as all kinds of racist things happened in school and microaggressions and macroaggressions happened.

SJ: That’s exactly what I mean when I say that we’re this weird in-between generation. We’ve inherited that ambivalence. I, too, was transformed by school. I loved school, even when it didn’t love me back, right? I was a good student whose mind and body aligned with the values privileged by our education system, and yet I was discouraged by racism at the highest academic levels. I loved it anyway, you know? I loved it. I am also aware this love represents conservatism—in the purest sense that I am emotionally invested in the oppressive system that shaped me and picked me. Academia is uniquely invested in reproducing its own conventions and values, and it self-selects for those who can succeed within its frameworks. I recognize that I am one of those people. Not only did I succeed, but the academic system succeeded in making me love it, despite the many ways it excludes. When I look at students who are not served by the system, I have so much love for them. I have so much love for the very fact of their defiance, defiance I wasn’t strong enough to summon for myself. Maybe I was too “good” of a student—I internalized their discipline too well—for certain kinds of defiance to even be accessible to me. You know what I mean?

GC: I do know. I mean I really do. Your optimism is so moving and the idea that other generations can see things that we can’t see. As a Gen X person, I often feel prickly because it feels like our ideas get left out or forgotten about. There’s a section of the déjà vu called “On Commemoration,” where I go back to something I wrote in the early 2000s and share it and look at it and acknowledge that I’m thinking differently now about some things—the world is different—but also not just disregarding or eschewing what came before. I want to be able to hold those realities at the same time, who I was and where I came from and where I am now. Maybe that’s your idea of us being able to look at both sides, being in that doorway.

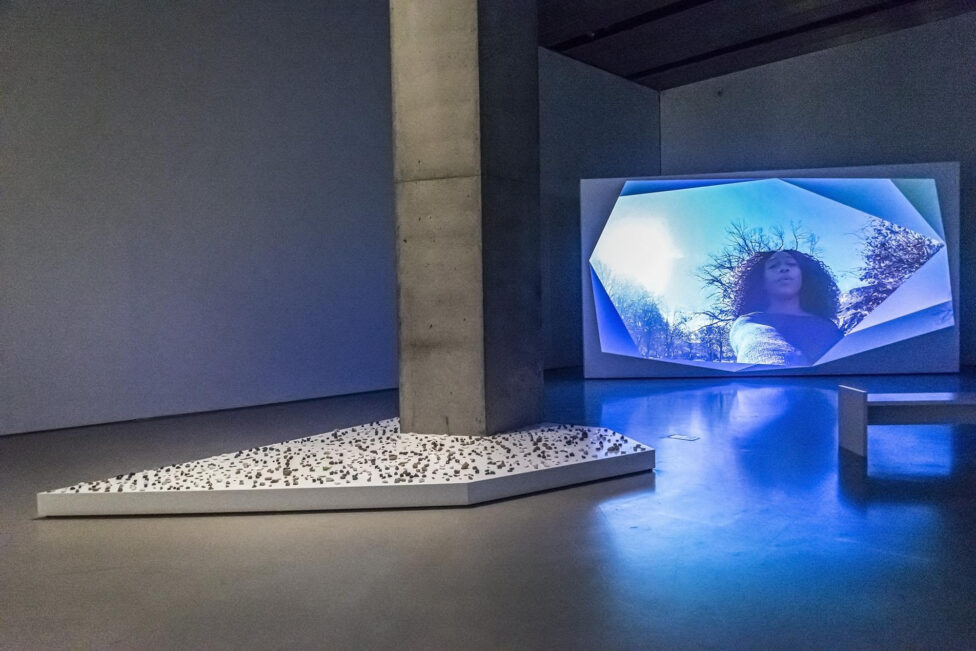

[ID: In the foreground, small pieces of glass, rocks, and pennies sit on a low standing irregular shaped plinth. In the right background, a projection screen depicts an image of a woman reaching her arm beyond the bottom center of the frame. Installation view: Steffani Jemison: End Over End, March 5 – August 8, 2021, Contemporary Arts Center, Cincinnati. Photograph by Jesse Ly. Courtesy of the artist, Greene Naftali, NY, and Annet Gelink, NL.]

SJ: I try to think of my in-between position as its own opportunity, its own advantage, its own superpower. To do that, I have to acknowledge that I will never have the same political convictions that I see in younger people. I don’t have an authentic relationship to certain positions—it would be hard for me to get there authentically via my own experiences—but I can defend the value of those positions and others, and I can defend everyone’s right to speak from exactly where they are. I recognize that the horizon that they see may be a little further than the horizon that I see. Maybe my role is to defend their right to do that, make space for them to do that.

A few years ago, I was teaching at a small liberal arts college. A single Black student had registered for my class; she was brilliant, but utterly uninterested in what we were doing together; she really was not feeling it. She barely engaged with my questions, no matter how hard I tried. At one point, I asked her what the problem was. One issue she mentioned: that I so often referred to objects and conversations that had unfolded in museums, which she opposed. They are purely extractive, she said. Keep in mind, she’s, like, 19, okay? She says, They are purely extractive. They are colonial institutions that can never, in any way, be extricated from the history of colonialism. There’s nothing to repair there. There’s nothing to recuperate. She was like, I cannot turn my energy and attention toward this desiccated skeleton of a cultural system that you’re trying to give me. Why would I? It is rotten. All this was very obvious to her.

I was shocked. First of all, when I was growing up, I studied what I opposed. As a kid, I understood that if I was assigned an essay by James Baldwin, what I was intended to be learning in school wasn’t what was literally in the essay. I was learning why people think what James Baldwin wrote was important. I was supposed to be absorbing a whole critical and conceptual paradigm within which this particularly literary work was meaningful. This paradigm is precisely what she was rejecting. She was unwilling to allow herself to be corrupted by internalizing a value system rooted in the contemporary art industry or the discourse of art history. Many years later, I remember having a conversation with a powerful person in relation to the work “Decolonize this Place” was doing in opposition to the Whitney Biennial. The person said (I paraphrase), These activists are so young. They don’t understand anything about how museums work. And I said (paraphrasing again): That is exactly why we have to listen to them. That’s exactly why. It’s true that they don’t understand. And we may never understand exactly what they say. Ultimately, though, we have to ask ourselves, do they have to be able to justify it to us? Do we have to understand for it to be true? What if we’re not going to be able to see it from where we sit? We have been shaped so deeply by the traditions we’ve inherited, but they haven’t: what if they can see something we can’t see? What if the activists’ refusal to understand how museums work is precisely the source of their vision?

GC: You have such a beautiful way of honoring what came before and also looking to the future. I think I’m still catching up or digging my heels a little into what was left behind. I’m super enthralled with the past, especially traditions of Black women who came before, especially people who I feel did not get their due. Wanda Coleman, for example. Or other poets I love like Anne Spencer, Naomi Long Madgett, or Dolores Kendrick and The Women of Plums. To understand and appreciate them, to even know about them, you have to have some tolerance or ability to engage with the systems they engaged and lived in and struggled with and often loved. If you’re not willing to do that, then they remain erased or become erased in a new way, flattened out or turned into someone else. Without a nuanced sense of context, which could include museums or other deeply problematic things, you lose the nuance of these people. You’re not really seeing them, you’re only seeing yourself, projecting backwards a version of yourself.

Growing up, I didn’t see many models of people like me living this life. But now the world is so blessed with our brilliance and talent! I remember the first time I found out that there were people who were Black and who were women and who were alive and that they wrote books. I didn’t even know that. It was in an Essence magazine. And it had Alice Walker and her 40-acre estate in California and the whole thing blew my mind. I was like, I don’t even understand this.

SJ: She was the first Black writer I learned about too, actually. My parents kept lots of books in the house, and my mom really sought out titles by Black authors. I remember we had Betsey Brown by Ntozake Shange. I remember every book by Walter Dean Myers. I also remember a book for young adults about a dark-skinned girl who had a lighter-skinned cousin, close in age, with hair so long, she could sit on it while she played piano. The cousin died young, I forget why. And then the other girl was left to reckon with the fact that she never would have long hair, but also got to live.

GC: That’s an amazing book. I want to read that. Actually, maybe you should rewrite a version of it just like you said. That’s so classic. She had long hair so long, she could sit on it, but then she died.

SJ: [laughs] I had a really vivid mental picture of what both of them must have looked like.

GC: Oh, yeah. I can see them now. But I mean, who is your work for? Do you feel like the art— the videos, the sculpture—has a different audience than the writing?

[ID: Gabrielle, in a white dress, kneels on an ornate orange and red rug with scraps of text scattered around her. Gabrielle holds a large fold of paper over her head with arms outstretched. Gabrielle Civil, ___ is the thing with feathers. Photograph by Dennie Eagleson. Courtesy of the artist.]

SJ: Honestly, this question of the audience of the work, the community for the work, has felt increasingly pressing for me. It feels more important than it ever has. Early in my artistic career, I took audience for granted. The audience was who came, basically. I certainly thought a lot about the artists with whom I am in community, mostly artists of color, as really important interlocutors. I also build my work in dialogue with other creative people—mostly Black creative people whose work doesn’t circulate in the art world—who sometimes end up as subjects of or collaborators in my work. Working so intimately with others adds another layer of accountability and another way of thinking about audience.

But lately—I’m being very candid—I have started to wonder if one of my goals in the coming years will be to bring new viewers and readers and thinkers into conversation around what’s important to me. Do I want to consider, if not orienting myself toward a broader audience, then at least making my ideas super clear to the audience that has found its way to my work?

These questions come up in relation to my half-hearted participation in social media. “Sabotage” would be a strong word, but I have certainly chosen not to take the easiest road when given opportunities that might have been life changing. I have often come up with weird moralizing explanations and justifications. The fact is, these choices often come from a place of comfort and fear of the unknown. Could I find more generosity in the relationship between my work and its communities? It’s a question I’ve been working through: what do I want? What am I afraid of?

GC: It’s super hard to figure all this out on your own, not least because the questions are really layered. I mean, those are ethical questions, moral questions. But then what you just said is that sometimes you wonder if your ethical or moral responses are also hiding another kind of response, which is around fear of success. You seem to me like a private person, and so maybe fear, too, of exposure, of having more eyes on you? I definitely relate to many of the things that you just said, although the stuff that I do is sort of weird…or maybe it isn’t that weird, but it isn’t as marketable.

SJ: Because you’re one of those people who can do EVERYTHING. Like, you have this book, and it’s like a zillion different books.

GC: Right, and maybe more people would be able to read and understand one book in a book, you know what I mean? [laughs]

SJ: Your book is beautiful, and all of us fellow weirdos, of course, appreciate the expansiveness and the multitudes it contains.

GC: Ahhh, thanks! And yeah, that’s the thing, I do believe that I’m a weirdo. And I love weirdos, and Black weirdos are the absolute best. When I find films or objects or books or poems by people who are a little off-kilter and aren’t saying exactly what people expect, I just feel so nourished and so happy.

I have a dream about starting an experimental pop-up school that would be around for a finite time. We would know from the start how long it would last and that it wouldn’t last forever. Some classes would be an hour or a weekend or a few weeks or whatever and some would last for a few years.. We would just experiment with different ways. Then after that finite time, we would sunset it, archive it, and take whatever was productive and give it to other people. The whole thing from rise to shine would last about five years.That’s a dream of mine. I guess the kind of school would be a Black Weirdo School. You know, you could go to hair school or nail school—this is Black Weirdo School, where you don’t have to be a Black weirdo to come. It’s like you don’t have to be Black to go to an HBCU, but that’s the ethos. Do you see what I’m saying? Just the thought makes me feel so alive! So energized. Maybe in Black Weirdo School, we go to Kentucky Fried Chicken, and we put up signs that ask questions about labor practices. And we also eat the biscuits there because we’re not perfect. Maybe we do that first, then hang the signs. I don’t know what we’re doing, but I think we should just be everywhere doing all kinds of things. Because what I am missing in so many institutions where I’ve been working is that kind of strangeness and zeal and access and mobility and simultaneity of people fussing and finessing over the right things. Biscuits at KFC! For Black Weirdos! Anyway, that’s a dream of mine. That and to try to make someone fund this. [laughs]

Also, wow, I feel like talking to you today has made me feel more cheerful. Thank you! My new book was supposed to come out this fall, and it got delayed, and that has been a real bummer for me.

[ID: A woman wearing a white dress and white gloves with her face painted white stands with her arms extended to the sides. In the background is a small stage with a row of chairs, a cross, and a person wearing all black standing on the left hand side. Steffani Jemison, Sensus Plenior (2017). HD video, black and white, sound. Installation view, Whitney Biennial, Whitney Museum (2019). Photograph by Ron Amstutz. Courtesy of the artist, Greene Naftali, NY, and Annet Gelink, NL.]

SJ: What do you mean? Another book?

GC: I know, it’s wild. the déjà vu came out in February and the new book was supposed to drop in October, believe it or not—but apparently there were supply chain issues so it had to be pushed and won’t be out for a while. I was in my feelings and then one of my friends said to me, I know you’re upset but you need to calm down. You’ve been pushing so hard, you need to rest. And that totally makes sense, but also, also these books are important to me. And I love them and want to keep them moving in the world.

SJ: I totally understand. I mean, I had a privileged experience with my little book because the publisher is small, so we were able to move from completion to publication really, really fast. But I will say I do find myself listening for signals from the universe. It comes because of this kind of openness that I have right now regarding what is next for me. I have lots of projects on the horizon, but I also feel that writing the book opened something different, a new direction, and I’m trying to listen to what that is at the same time as I’m trying to be attentive to everything that I want to do. And I also feel—maybe connected to the generational drive that I talked about earlier, the generational position—a strong obligation not to squander what I’ve built or squander my potential or squander the possibilities. It’s as if I owe it to the community that has assembled in connection with my work to follow things through. Whereas I often internally feel mercurial, drawn in different directions, not dissimilar to what I witness in your work.

You created a single book that invites us to understand the way that we are simultaneously inhabiting not only different times in different places, but also this porous way in which the many different creative lives we’re living are all at once, and how wild that actually is. To recognize that it really is all one life.

GC: I’m so curious about what can happen in one life, in what a person can do, in what I can do. What can I contribute? What can I offer? I feel like a word like “accountability” is trying to get at an older idea of “duty,” although those words feel different tonally and generationally. They both are about showing up—how can I show up for others? And how can I show up for myself? How are those things sometimes in conflict with one another? How can we be in better balance? And with our own work? This requires deliberate attention. If you do a lot of different kinds of work, you can’t do it all at the same time. Trying to figure out how to prioritize that becomes a question of how you spend your time. And you really can’t do that wrong. Because any one of those things is wonderful, you know?

[Cover Image ID: Gabrielle lies on the ground of a stage in a red tule dress and stockings with her lower legs resting on a red chair. Her head is hidden under layers of her dress as she holds a flashlight up to an opened magazine. Two loose flower stems rest nearby. Gabrielle Civil, * a n e m o n e. Photograph by Sayge Carroll. Courtesy of the artist.]