Will Rawls: What’s the meaning of life?

Moriah Evans: I cannot believe you are asking me that.

WR: I ask because you appreciate absurdity as much as I do.

ME: Didn’t Kant say something to the effect of… to have something to be busy with, to love someone or something, and something to hope for?

WR: Do you have those things?

ME: Do I have those things today, July 20, 2014?

WR: Yes.

ME: I have a lot of things to hope for. I have a lot of things to do [laughs]. More than I can handle. I have lots of people I love. It’s all keeping me occupied.

WR: How do you interpret Kant saying that it’s important to have something hope for?

ME: You know Junot Diaz, the writer?

WR: Yeah.

ME: I like him. In his recent novel, This is How You Lose Her, there is one sentence where he writes “This is what I know: people’s hopes go on forever.” He’s talking about the immigrant experience and how disappointing or incredible it can be. He’s talking about humanity in general too.

WR: Is the presence of hope destructive on some level?

ME: Well, yes. People get short changed. The United States of America—the land of oppression with the illusion of opportunity—meanwhile I am still victim to yet inspired by ideas such as “The Audacity of Hope.” Hope gives one or a community a space to envision possibilities.

WR: I think of what you do as being motivated with a sense of urgency. For you there are stakes.

ME: Hell yeah! There are stakes. There are stakes in everything.

WR: The fact that we’re negotiating a world full of stakes isn’t always so clear. Or, a sense of stakes can be pushed to the back of the mind.

How is choreography a means to engage with the world around you, to deal with questions of stakes and illusions?

ME: Aesthetically, you have to decide whether you are into [laughs] interviews or not.

WR: OK. [laughs]

ME: Um, [laughs]. I think choreography is everywhere; it is all the time. We’re choreographed by society’s perceptions and social rubrics. Choreography is hegemonic as it constantly operates through the state, our identities, the color of our skin, gender, fashion, affluence, poverty, et cetera et cetera. To decompress these days, I am enjoying watching spectacular choreographies circulated via YouTube. For instance, North Korea’s Mass Games Arirang Festival is heralded as the world’s biggest choreographed performance. Talk about precision choreography serving the ideology of the state. Those millions of detailed actions churn into an illusion, which is full of stakes. Actions are the substance of our lives. Illusions and stakes enable us to act.

WR: You watch that to decompress? I’ve noticed in the last ten years the word choreography appears much more often in periodicals about things that have nothing to do with dance. In college I could count the times I read the word choreography outside of a dance book and now it’s—

ME: —pervasive.

Maybe people are accounting differently for the systems that control our behavior and interactions. Who and what choreographs the way that society functions? When does the system choreograph us and when do we choreograph the system? How does agency operate?

WR: In your choreography do you feel that you are practicing those questions?

ME: Always. An expanded sense of the term choreography has been theorized for a long time and brought into focused, understandable definition since the 1990s. I operate aware of that history in my practice, especially through projects with The Bureau for the Future of Choreography, an apparatus striving for collective authorship. The Bureau means to increase agency for its participants and in the process transparently host complex relations between authors, institutions, dancers, choreographers, fact, fiction.

One reason why I love dance—and I use the word dance and not choreography—is that dance can escape or evade or decimate choreography. Institutional critique must be contained within the form—of an action, of a dance step, of the frame and viewpoint onto the work.

Portrait of The Bureau for the Future of Choreography as Rocks (Moriah Evans, Sarah Beth Percival, Evelyn Donnelly, Stina Nyberg, Suzan Polat, Alan Calpe), New Museum, Fall 2012

Photo Courtesy of The Bureau for the Future of Choreography

ID: Surrounded by musical equipments, several people “rock it out,” exuding a general sense of ecstasy.

WR: How do we take up choreography as a system of power relations, and then use dance to challenge those relations? To undo choreography even as it unfolds in a performance?

ME: The erasure of choreography is something that I have been busy with in my studio practice while in residence at Issue Project Room this year. I’ve been seeking steps, moments, and approaches that produce a conflict between the choreography and the dance. Can a dancing body or person supersede the choreography so that choreography enters a state of dance?

WR: What does the residency entail?

ME: They give you a lot of support in terms of space, time. Lawrence Kumpf, the artistic director at Issue is incredibly open, generous and supportive. The space is within a Beaux Arts building designed by McKim, Mead & White in 1926 and originally built for the House of Elks. It then became a draft registration site and the Board of Education. The building was bought and developed into luxury condos by Two Trees Management. A portion of the building is reserved for art, and Issue Project Room was awarded the 20-year, rent-free lease in 2008. It’s this strange ballroom cum meeting hall cum concert hall cum theater space. I love it. And the site is significantly influencing what I’m up to. That room might be making the dance.

WR: There’s a layered history of social choreographies in that building. Are the influences of Issue Project Room’s room a welcome choreographic imposition?

ME: It’s early; we’ve been working in the space consistently. I can’t go into much detail about what the piece is yet. We are developing a system and practice of dancing together: being in that room together and moving in constant relation. Dance exercise as ritual. The dance is starting to make itself in certain ways.

WR: Dance exercised as ritual?

ME: Well both, dance exercise.

WR: With and without a “D”.

ME: Dance exercised as ritual or dance exercise as ritual, as being together, as people active in space and time being in relationship to a room, to a position, to step, to one’s own dance history, to one another.

WR: To step? Meaning?

ME: To a step. What is the essence of a step? How to chase the essence of a step? How to re-approach that step again and again? How to situate subjectivity or energy in relationship to that step? What state to approach that step from? What state does that step lead into? How do I do that step for someone with whom I am dancing? How do I do that step for myself? What are the distinctions between doing a step for the doing of it as opposed to the display of it? So I’m asking these questions. But I’m trying to answer your question.

We are working with a spatial pattern taken from a solo I developed for Maggie Cloud last summer in an LMCC [Lower Manhattan Cultural Council] Swing Space Residency. The residency was located in a former Express store at the end of Pier 17. It was bizarre–a remnant of consumerism on the edge of water. I had a friend do architectural renderings of the space, a CAD drawing, and then we digitally placed it into the water. The idea was that it was “at retail’s end” [both laugh]. It was like a boat. The pattern has 14 actions, which can repeat while traversing space in four quadrants. It can be done with a partner in order to mirror, oppose, and unify two bodies. At Issue, the pattern has become quite systematic. Sometimes it feels like I am making a dance machine. Or a dance boat.

WR: The relationship between choreography, steps, and the energetic effect of these steps seems like a larger theme in your work. In an older piece you made with Sarah Beth Percival in 2012 that you performed in Zurich—

ME: —in Geneva. Le Théâtre de l’Usine.

WR: The name of the piece was…

ME: Out of and Into (8/8): STUFF. That’s an old piece that Ben Pryor recently invited us to remount for American Realness in New York City.

Out of and Into (8/8): STUFF (Sarah Beth Percival, Moriah Evans; Costumes: Evelyn Donnelly), American Realness Festival 2014, Abrons Art Center, New York, NY USA

Photo by Ian Douglas

ID: Dressed in white unitards with colorful and floral accentuation, two performers are opposite of each other on all four. Almost mirroring each other, their long heir is suspended in the air, their backs are arched, their mouths are softly open, creating an abstractly gentle atmosphere.

WR: This piece also has a quadrant structure and a rigorous set of mirroring patterns.

ME: That duet was dealing with so much! We can do a whole interview on that duet—there was a ton of research that went into that piece. Attempts to navigate our bodies as bold, loathsome, abject, horrifying, and horrified; emotions in dialogic relations; the pursuit of slapstick hysteria. The system through which we traverse the space is a reference to Beckett’s Quad, a television play from 1981. The dancing was amorphous, messy, and based in flesh; we needed a formal means through which to distribute this information. I’m obsessed with space. Space is somehow spiritual. And I mean spiritual in an open, existential sense of that word.

WR: Quad is a beautiful piece. And haunting. It has a strong hypnotic and ritualistic feeling to it. There’s a punishing, repetitive physicality in Out of and Into (8/8): STUFF; it produces a hysterical or humorous sensation in the room; the dance spills over.

ME: Minimalist hot mess.

WR: [laughs]

So you have this ongoing solo choreographic practice, but you also work in other capacities. You work as editor-in-chief of the Movement Research Performance Journal. But I’d like to talk about your work with The Bureau for the Future of Choreography.

ME: Alrighty then.

WR: How did The Bureau get started?

ME: I had a desire for a few years to create a collective think tank with friends and colleagues. Where people could gather to discuss work and practices from a variety of disciplines. In the back of my mind, I was thinking about modes of production in art and how to conceptualize a dance company for the 21st century. Sometimes we joke that The Bureau is a fake dance company.

I have a complicated relationship to authorship. Is authorship the answer or is it a big problem? The roles of “choreographer”, “dancer”, “collaborator,” et cetera, are so interdependent; meanwhile, there’s a market system hungry for the success of the individual author. I have always felt that we’re not challenging ideas of authorship in dance enough as artists. And when we do, critique often functions to yet again celebrate the author. The tension doesn’t get exploded. I struggle with this and I’m interested to stage that struggle. The Bureau is a site where these types kinds of questions are instigated and provoked.

WR: Did you feel the community wasn’t asking the kinds of questions you wanted to ask?

ME: I didn’t feel part of a group that was asking those questions or doing things in a structured way that was über sincere, hyper naïve, incredibly sophisticated, and hopefully radical.

WR: That’s a lot to pull off at once.

ME: Yes. But what’s the point of doing anything if it’s not impossible!

I had been participating in an international collective, INCONSUMIVEL. INCONSUMIVEL gathers artists in a residency format focused on a particular set of questions. Eventually, they place a fragment of their research in a box. This box circulates among communities around the world–like a message in a bottle. All INCONSUMIVEL projects must begin with opening the box and retrieving what is there from the previous working groups. In Spring 2010, Ondrej Vidlar, Sarah Beth Percival, Mina Nishimura and I worked on an INCONSUMIVEL project in which we came up with a score.

WR: Desire Dances.

ME: Yes. How do you dance, why do you dance, why would you dance, how do you dance with desire, how do you dance without desire?

WR: When I went to witness it, and was turned into a participant, the instructions were: Do a dance of desire. Do a dance of the—

ME: Erasure

WR: —erasure of desire. Do a dance of desire with arms. Do a dance of the erasure of desire with arms.

ME: Or, do a dance of desire without arms. An assertion was given and then taken away.

Desire Dances

(take a moment to find stillness and emptiness)

Dance of desire

Dance of erasure of desire

Dance of desire with objects

Dance of erasure of desire with objects

Dance of desire without face

Dance of erasure of desire without face

(find a way to show your face)

Dance of transforming your desire

Dance of removing your desire by transformation

Dance of doing what you do not want to do

Dance of memories of desire

Dance of desire without arms (crossing the space)

Dance of erasure of desire without arms (in channels of the space)

Dance of desire without legs

Dance of erasure of desire without legs

Dance of desire without sex

Dance of erasure of desire without sex

(take a moment to look around and find your vision. look at everything and be sure to move your head. eat space with your eyes. slowly lose your sight and begin…)

Dance of desire without sight

Dance of erasure of desire without sight

(find your soul and look at me)

Dance of desire with soul

Dance of erasure of desire without soul

Dance of desire without body

WR: This question of desire was so central to initiating The Bureau. Why desire?

ME: There must have been something in that box that instigated it. I would have to go through old notebooks to really recall. But, to go back to your first question, we always have to have something to hope for, a will to action. Can we act without will? Can we dance without desire? The score perhaps makes for bad improvisation [laughs].

WR: Is the wish to forward one’s authorship the same thing as answering one’s desire? How do ambition and desire become mutually exclusive in this—

ME: —quest…

It depends upon the individual artist. But, no. Or yes and no.

It was the spring of 2011; we would practice the Desire Dances score outside in public space. It was Louise Höjer, Emma Kim Hagdahl, Kyli Kleven, Sarah Beth Percival, Julia Simpson, Anna Whaley and me. Asad Raza was participating in some of our meetings. Eventually in June, we did a Judson [Memorial Church presentation through Movement Research], and Gui Garrido and Pieter Ampe performed with us. You were our coach at Judson. Visual artist, Evelyn Donnelly, and I made those Mylar, sound-generating costumes and blue cutouts over a single weekend. That whole moment was ambitious and fun. In part, it was spectacle as a form of announcement, of the birth of The Bureau.

WR: So how do you become a member of The Bureau for the Future of Choreography? It’s perhaps a silly question, since I am a member. But each Bureau member might have a different response.

ME: Anybody can be an agent of The Bureau. They just have to show up and participate. It’s also possible to send us an email at dearBFC@gmail.com to find out more.

WR: How did you settle upon the name?

ME: It took a year to come up with the name—The Bureau for the Future of Choreography. It’s slightly obnoxious in that it sounds officious. It’s bombastic. It’s also supposed to be funny—I really hope people can recognize the humor and absurdity of The Bureau’s activities. And it’s a conceptual proposition. If you say, “The Bureau for the Future of Choreography,” a likely next question will be, “What is the Bureau for the Future of Choreography?” We have a score called The Bureau for the Future of Choreography is… in which different agents of The Bureau provide different answers. Consensus is not the aim.

The Bureau is young, a four-year-old project. There have been about forty different people involved in varying capacities so far; we keep a thorough list of all these collaborators, participants, and agents. Sometimes there is an idea afloat that if one encounters a Bureau project they automatically become part of it. It’s quite viral.

WR: And absorptive. It’s a blob.

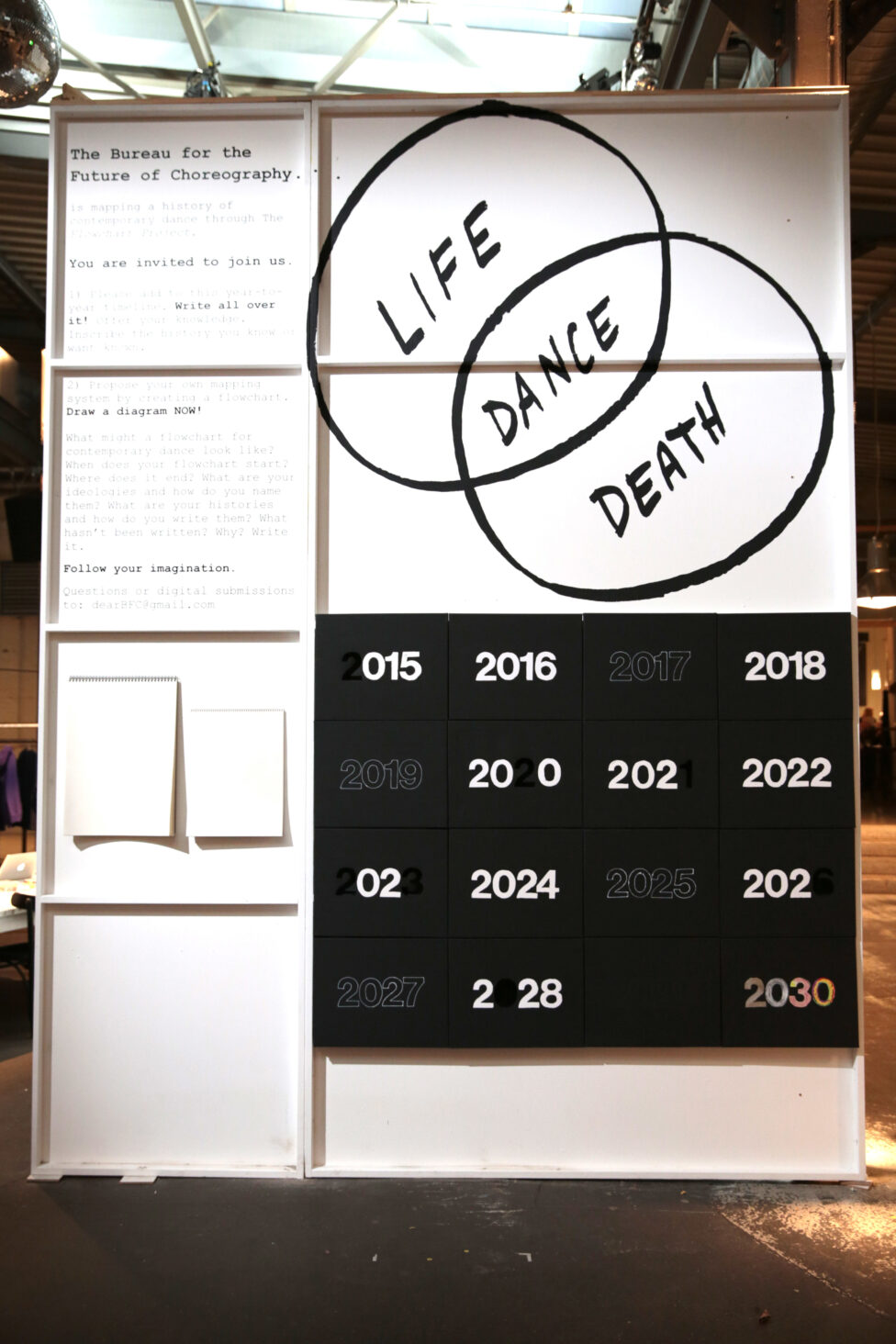

The Flowchart Project: Timeline at American Realness Festival 2013, Abrons Art Center, New York, NY, USA (detail)

Photo by Kenan Halabi

ID: A large cardboard box with pens and paper on top is positioned in the middle of a small room, occupied by a few people whose figures are blurred. The translucent walls are busily cluttered with colorful drawings, such as Fluxus, AIDS, 9-11, Occupy.

ME: A swarm. It contaminates. Hopefully for good! We can all criticize it, and we do. It’s absurd and fun, and yet also sincere and serious. It’s about research and play. How can we artists assume institutional power?

Anyway, anybody can join. We’re really serious about that.

WR: I know we are.

ME: For real. If you wear a T-shirt that we’ve made, you’re implicated.

WR: The T-shirt has the words—

ME: Life. Dance. Death.

REPOSE (a work by Moriah Evans, Rockaway Beach, Beach Sessions 2021). Performer: Irene Hultman

Photo by Maria Baranova.

ID: A performer with bright neon green shirt and shorts lies down in the sand. Populated all over the costume are Venn Diagrams that say “Life, Dance, Death” (with Dance in the middle of the two circles of Life and Death).

ME: A few things have become clear about how The Bureau is working: it is inherently collaborative and almost all of our projects, and we might make this a requirement, begin with an open call to action. A score. The score can be anything. For instance, The Flowchart Project is a monstrous score. The Bureau sent out hundreds of emails to dance artists, historians, and theorists inviting them to map the past fifty years in contemporary performance, and also postulate the future.

WR: This Flowchart Project is really exciting.

ME: It takes as a point of departure Alfred Barr’s Flowchart of Modernism from 1935. Barr was an American art historian and the first director of the Museum of Modern Art. He formulated a diagram to graphically explain the development of modern Western art. It’s a universalist gesture, done by a white man, at the center of power, which MoMA still exercises. Although, yes, MoMA critiques it even to this day through various collecting and programming initiatives. And Barr has been critiqued ad nauseam.

WR: He also revised the chart periodically over his career.

ME: Yeah. And many people have revised that chart. And responded to it with spoofs et cetera. It has always occurred to me that we do not have a similar set of discussions in contemporary dance and performance. In our form, there is so much knowledge that is stored in people’s lives and revised in their artistic practices. Yet so many performances get erased. So much information is being generated and accumulated by and in performance communities that isn’t stored anywhere externally.

WR: A performance disappears because there isn’t a record, but we all write. That’s one of the things the Bureau proposes—that we write. And, more broadly, practice recording.

ME: The Flowchart Project says that any point of view is valid and that we can’t have a universalized chart anymore.

WR: Can you describe how it is installed in space?

ME: We’ve done The Flowchart Project three times so far, once a year since the project has been conceived. The first time was for the Movement Research Spring Festival in 2012, then at American Realness in 2013, and then at the Tanzplattform at Kamp Nagel in Hamburg, Germany in 2014.

Each iteration of the project shifts its form; however, the three basic components are: a timeline running from 1960 until 2020 or 2030; a station in which people diagram their own flowcharts and sketches of history; and a station at which we silkscreen flowcharts on T-shirts and other items that function as logos for the project, essentially costuming the crowd in enthusiastic Bureau-wear. If people wear these tees in their lives, the limits of the project extend further.

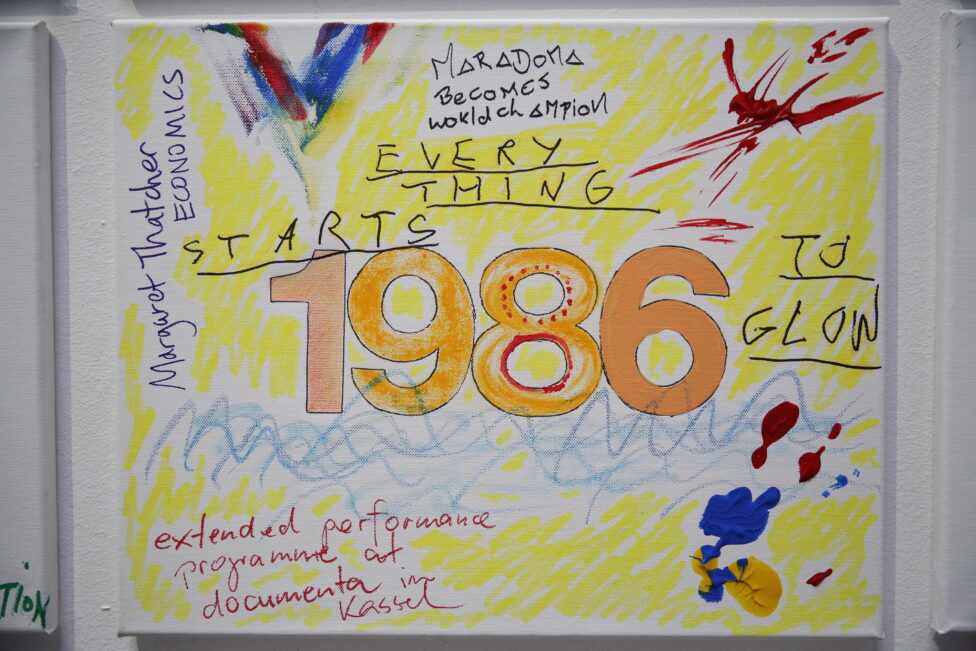

The Flowchart Project: Timeline at Tanzplattform 2014, Kamp Nagel, Hamburg, Germany (detail)

Photo by Anja Beutler

ID: A clash of bright colors on a white canvas with the word “1986” prominently featured in the center. Around “1986” are some sparse texts in different handwriting, such as “Madonna becomes world champion.”

ME: The monumental timeline created during an installation of The Flowchart Project is dismantled at its completion so this call toward monumentality is ultimately destroyed. We’re no MoMA. We’re not keeping the history intact. We are constantly rewriting it, reimagining it, and tearing it down. It’s a performing of archiving—a performance of the gesture of writing history; but it’s not ironic. There is a lot of content that is being generated and shared, but it is not only coming top down from experts. Meanwhile, we collect all the flowcharts, even ones made by three-year olds.

WR: Three-year olds?

ME: I’m serious. When someone’s little kid tries to make a drawing at our Flowchart Station, we keep that performative expression in this giant notebook with all the others. The project builds upon itself each time we do it. It’s really alive and incredibly specific to the context and scene that invites it. The results of the project are not being stored away as fact or sacred object. It’s DIY. The Flowchart Project produces a site for the residue of performance and the multiplicity of its histories.

The Bureau is busy with myth.

WR: Myth makes me think of DIY. And cultural ventriloquism. Why is myth important?

ME: Myth unravels and re-monumentalizes. It keeps going on and on.

WR: Is dance a form of oral history?

The Flowchart Project: Timeline at Tanzplattform 2014, Kamp Nagel, Hamburg, Germany (detail)

Photo by Anja Beutler

ID: A large white wall is erected in the middle of the room. This wall is neatly divided into smaller different-sized rectangles that contain the “Life Dance Death” Venn diagram, a blackboard section listing years from 2015 to 2030, though some numbers are obscured.

ME: Through the body and yes. The Bureau’s calls-to-action can be answered or executed or danced so diversely. It’s living in a legacy of the Judson era ideas, where any body [can dance]. Harnessing the energy of a multiplicity.

One of the key people who is super involved with The Bureau is Evelyn Donnelly. She’s a co-conspirator and visual strategist for The Bureau, among other things. She’s a visual artist who works in many media, including performance. Architect, Steve Gertner has joined us for a project. Writer and poet, Claudia La Rocco, recently became an agent. Maybe she can take the play of language at The Bureau to the next level. Choreography inherently encompasses other forms. The Bureau is conceived to move into larger domains and pose questions about choreography with all sorts of people.

WR: What’s next for The Bureau?

ME: Right now we’re working on making a dance marathon. What is a dance marathon in 2014? What are the histories of dance marathons in the USA? There were the dance marathons in the 1920s during the Depression through which people used to try and get money, as commemorated in the book, They Shoot Horses, Don’t They?, as well as in the movie [written by Horace McCoy, directed by Sidney Pollack, respectively].

WR: With Jane Fonda.

ME: Today, dance marathons are major fundraising events on college campuses. They are often organized to raise money for Children’s Miracle Network Hospital.

Is our dance marathon going to be a relay? Is it about exhaustion and time? Is it about partner dancing? The marathon is harnessed as a choreography to move a larger community.

WR: Maybe The Bureau will only know after the fact. At the end of every Bureau session, a photo is taken of the people that were present. Is that still happening?

ME: Yes. We have mythic Bureau portraits. It’s a score. We also did a marathon of the Score for Proposing Scores. Every score had to be 26 minutes 2 seconds long. And we have that awesome photo timer so we really can time 26 minutes and 2 seconds!

WR: When is the marathon?

ME: When is it going to happen [whistles]? We don’t know; we are going to start working on it again in September. We did some basic dance marathon trials during The Bureau’s LMCC residency at Governors Island. They were interesting. Especially the first one, which was less arty and just open space. We kept dancing and the public joined. Some of The Bureau criticized itself: “It was like a wedding.” But others loved that anybody could come in and dance. Can a dance marathon be positive? Or does it have to be abusive? [laughs]

Dance Marathon Trial, LMCC Governors Island, New York, NY USA

Photo by Adam Macchia

ID: Different people, visually from different age groups and different racial backgrounds, look happy dancing together in a studio. Dressed in comfortable summer clothes, some barefoot, some in sneakers, some in slippers, they all embody different shapes and qualities of movement.

ME: The Bureau is committed to the idea of a marathon. Where. When. Is still being finalized.

It becomes hard because most people who are involved with The Bureau are active in their own domains outside of The Bureau. Agents of The Bureau are also individual authors—and that’s the proposition, the people who participate in The Bureau are free to manipulate and re-orient what it can be—maybe not entirely but certainly many aspects of it. We need spaces to work through ideas together as artists. I dunno, forces of people change history. What do you think?

WR: The Bureau’s bio announces that it produces documents, choreographies, and perceptions about contemporary dance. Where do these documents exist and how can people find them?

ME: We’re trying to make our archive online.

WR: A score for proposing an online archive?

ME: We have debates within The Bureau about this.

WR: I bet.

ME: The Bureau participates in the internet; it’s a symptom of existing in public space today. When The Bureau is online it needs to use the choreography of the internet, not to the ends of garnering visibility, but to the ends of play and discussion. Not to say that accessibility is not wanted. Right now we’re creating .pdfs of every document that The Bureau has ever made and figuring out how to collect it somewhere.

WR: OK, moving away from The Bureau now and back to Moriah.

ME: I don’t own The Bureau. I try to keep it conceptually intact from day to day while we explore collaboration at different levels of responsibility. Sometimes I like to think of The Bureau as fascist and totalitarian and extreme and viral and Weapons of Mass Destruction! Obviously delusions of grandeur at odds with democratic process [laughs]. But why not? Let’s have fun with it. I love the potential for absurd play.

WR: Seems that the dance of maintaining the existence of The Bureau erodes its choreographic endeavors. But isn’t this a kind of success, ideologically speaking? The dance is decimating the choreography in a way that you are seeking in your solo projects.

When you come home from The Bureau, do you feel that you are still part of something?

ME: I really feel inspired by my collaborators and friends. And I think it’s cool when people come to work at The Bureau; it’s a place for authors to fight with each other, eventually, hopefully, in a productive way.

The Bureau hopes to be generous.

WR: It’s inconsistent. But so is making things. At least, for me, Will Rawls, The Bureau seems to frame and re-frame that inconsistency.

ME: Dance is deeply inefficient. I feel we perform that inefficiency as laborers in our field. The Bureau is always in a state of constant redefinition and, because of this, is a dance. Dance is always in a state of redefinition.

Cover Image Description:

A performer with bright neon green shirt and shorts lies down in the sand. Populated all over the costume are Venn Diagrams that say “Life, Dance, Death” (with Dance in the middle of the two circles of Life and Death).