River Whittle: Let’s see, when I think about how I (as an artist) am able to sustain my relationship between creative work, my spiritual practices and my activism I would say that it’s through community work.

It’s really hard, I have non-physical disabilities that make it pretty difficult for me to be very organized and maintain a neat schedule. But usually, I get reminded that I’m focusing on one thing. I’m really focused on the creative, the creative is tied with (as a low income artist) my survival. And so, a lot of times, even my creativity will not be as focused on just the creative or the spiritual. It’s focused on: How can I sell this? And when I’m reminded of that, I feel off-balance. Moments like that really remind me: I need to be creating just for the sake of creating. Which is more spiritual.

I’ve been spending a lot of time trying to figure out how to have enough money to survive. So I’ve been less plugged into community events and such. And then I’m like: “Okay, let me go back to this place of ‘what can I do that’s proactive’ and this place of ‘I’m trying to work more from a place of abundance, and less from just being in survival mode.” That’s hard sometimes, when I have to be in survival mode.

But also, Indigenous people are very good at seeing abundance in life, even materially. We have had very little, so I’m trying to re-center myself with that. I try to interweave and connect my creative, community, and spiritual practices. That’s how I make it sustainable for myself. But it’s a challenge and it’s something I’m definitely still thinking through.

Emily Johnson: Yeah, you said something about creativity being tied to survival—at that moment I knew you were speaking of resources. That is my life too. My life is supported by the work that I make and the work that I do with communities. So it’s similarly intertwined.

Maybe because it is intertwined, I can’t separate the making part from the spiritual part and the activist part. It just makes sense in my mind and in my body. I guess as somebody who works in a body-based form (where everything comes from my body) it’s intertwined within me also.

River Whittle / LANDBACK, LANDBACK.Art, 2022. Artwork by River Whittle. Photo by River Whittle.

[ID: A rectangular billoard rests over the desert land in Apache territory (Alamogordo, NM). Dark-green bushes below the billboard contrast with the mountains in the background and the clear blue sky. The billboard displays a face carved into a copper-colored material and reads “the land needs its people.” Billboard artwork by River Whittle, part of the project LANDBACK.Art.]

EJ: At a recent convening of artists, we were talking about fundraising and grants that we as artists need and critique, and how we could try to think about it abundantly. And when we were discussing this with a funder, I said something like: “I get grants to make dances but really, I’m reworlding.”

When I think about how things are together, in my work and in my life, that’s where my thinking goes. How do we, as artists coming together, as groups of people coming together, audiences, as land defenders coming together; how are we reworlding?

RW: If things don’t change very quickly, New York City is going to be underwater. I find a huge sense of peace in that. And I also feel very stressed, because of the people who do not have resources in the area and what will happen to them when that happens. So it’s kind of a two-fold thing, right? I feel this sense of comfort in the fact that the Earth is gonna protect itself no matter what, themself no matter what. But it’s also about minimizing the harm that will happen to the people when that happens.

I just think about the CEOs of these banks and these oil companies. Do they think that they’re bigger than the Earth? I mean, they do, they’re trying to go to space. It’s a lot of work. And it’s all interconnected. And as someone who’s doing this work, I feel like I do have to think about these things. I want to get to a point where I feel like I’m making a large impact. And I have time.

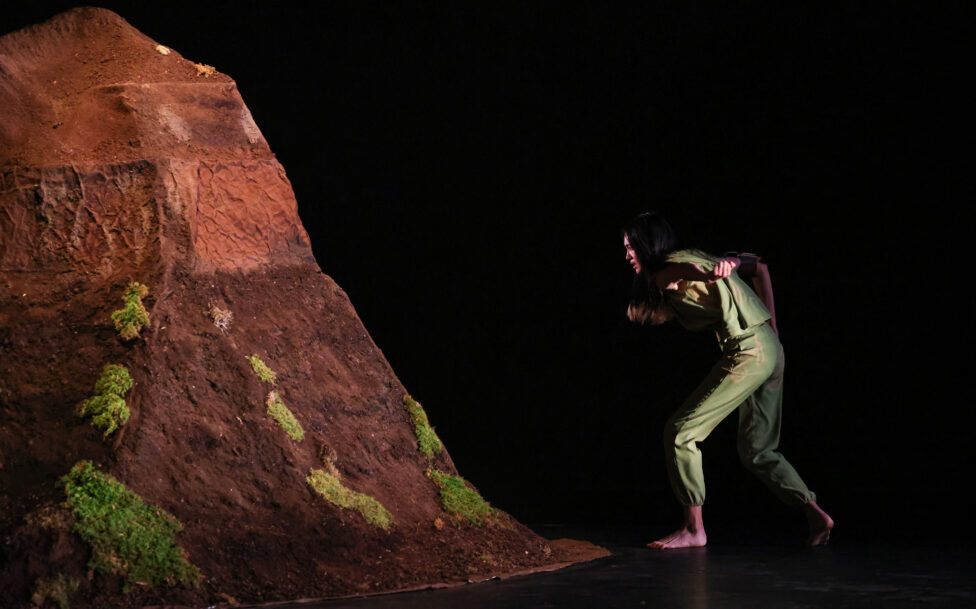

Emily Johnson / Catalyst, Being Future Being, 2022. Performance view featuring Sugar Vendil, presented by New York Live Arts. Photo by Caitlin Ochs.

[ID: A person with long dark hair in an olive green outfit is onstage lunging towards a set piece of a brown mountain with green moss along the side]

EJ: I feel the Earth moving this way, too. This action that grew out of the last few years, which I’ve been calling and thinking about as the Rising Stomp. It has come from the ground. It’s a physical action, we do this physical action in Being Future Being, we’ve done it in protests and in lots of different forms in the last year and a half. It really came out of this time, and it feels like it just came through my body.

When I do this, stomp, I’m thinking of the ground lifting up underneath, right? And usually I’m inside a building or I’m on concrete or I’m on a stage or something. But I’m feeling and I’m thinking about the land coming up underneath my feet. And there’s this very real movement that’s happening.

And there’s a very real exchange that’s happening between our bodies, the Earth body and my body or anybody’s body who’s doing the stomp. It’s in this lift, it’s in this in-between space—it’s not in the landing, it’s not in the sound, it’s not when you come down—it’s in that up, it’s in that lift. When I think about this particular movement, and when I do this particular movement, I know that it comes from the land itself, and the land taught me this.

When I visited last summer, my mom told me this story that she read: when COVID first started, a lot of humans stopped a lot of the rumbling around that which we usually do and construction and traffic and all of that stopped. She said that—it’s obvious, but it was so poetic for me to hear it—the Earth got quiet. Things got quiet. And so the Earth could be heard.

What I keep thinking of is all the other humans and our more-than-human kin who are in a reciprocal, or trying to be in a reciprocal, relationship with the land and the Earth. What have we learned during this time? You mentioned other people learning and maybe not even knowing yet or not having words yet about the ways in which they are being accomplices or allies.

I think about the land teaching us how to be accomplices, how to be allies, and that comes in many different forms. I think of the rising stomp and I think of what else the land is showing us, is sharing with us at this time. I think of our relatives, the children, the small ancestors who have been found in recent time in the land, which we knew were there, but now we know in some cases, specifically where. That came from the ground. That came from the land.

River Whittle / LANDBACK, LANDBACK.Art, 2022. Artwork by River Whittle. Photo by River Whittle.

[ID: Image of the NYC skyline with “lenapehoking” written across in red script. Billboard artwork by River Whittle, part of the project LANDBACK.Art.]

How do we manage the protection of land and kin? And our more-than-human kin? And how do we stay in a learning process with our kin and with Earth? And how do we fight those CEOs and capitalism managers that you already mentioned? And how do we stay in real radical acts of care? And how do we extend and be supportive and be part of mutual aid networks?

RW: There’s a lot of negativity that you can focus on, as a Lenape person coming back to our homelands. But it’s been really nice to develop a project that’s focusing on the positive and what we want to do, what we want to make happen. It’s been really incredible to be resourced and have people who know how to navigate institutions and grants…

Indigenous people… we have the solutions. We literally have the solutions.