Within dance, what do we hold onto as our relationship to the form, to the field, to our bodies, and to one another evolve over time? I invited Annie Dwyer (my longtime teacher, mentor, and dear friend) and Sherone Price (another brilliant educator, and one of Annie’s first students at Northwood High in Pittsboro, NC from 1977-78) into this conversation together about what it means to become an elder or mentor in the (often youth-focused) world of dance. Annie is a white woman in her 70s, technically retired (though still teaching) after decades of inspiring a love of dance in her elementary-through-high school aged students (many of whom have gone on to professional dance careers of their own). Sherone is a Black man in his 60s who is an associate professor at Appalachian State University, as well as a long-time teacher at the American Dance Festival, and a founding member of the African American Dance Ensemble under the direction of Baba Chuck Davis. What follows is a conversation not only about aging in the field of dance, but also about the evolution of a friendship, the non-linearity of mentorship, and the magic of messing up.

—Leah Wilks, Guest editor

This conversation has been edited for the purpose of publication.

Annie Dwyer

The definition of a mentor I thought was beautiful. I should go to the dictionary more often! [laughs] “A mentor is an experienced and trusted advisor who gives to another person advice and help over time, tools to be a better version of themselves willing to devote time and energy to advise above and beyond normal responsibilities.” But it said, “an elder is not defined by age, but rather has earned the respect of their community through wisdom, harmony and balance of their actions to their teachings. Not necessarily older, but able to share in a way that is useful to others.”

Sherone Price

I think mentorship lends itself to friendship. But I wonder whether or not eldership actually does the same? I don’t know. I think of mentorship as something that is moving, we’re always moving towards. There have been many times that I have introduced Annie as my high school dance teacher…

AD

…and people go “Oh my gosh!”

SP

And then Annie one day said to me: “Sherone, we’ve been friends a long time.” And you know Annie, we have! [laughs].

AD

I kinda always thought of myself as… even with little kids [I was teaching] that they were… with you that you were ‘eldering’ me, or I was ‘eldering’ you in different conversations, or moments along the continuum, rather than at some place where it switched.

SP

Right. The question comes up all the time for me with African dance when people call you the term ‘Baba,’ like with Baba Chuck Davis.* And most of the time the term Baba comes up, as a person who is considered an elder, a person who has age over you, but also has wisdom over you, and has done a lot of different things in their lives. And they help to guide you with thoughts as well. To me, it’s a title that people who honor you give to you. More so than the actual idea that you call yourself something else.

AD

Oh I see. That’s what I was gonna ask. So you see it as something that is given to you and that someone has noticed in you. [Something] that you earn or deserve.

SP

Exactly. I meet people who have said: “call me Baba so and so.” And it’s like, well do you know that person yet? So, why would they call you Baba when you haven’t really done anything in their lives to earn that respect in that way? I think Baba is earned…mentoring somebody for a long period of time, and then you become their Baba, in some way. That’s the way I always thought of it. I think you have always been my mentor because I’ve always enjoyed watching things that you do when you’re teaching. I would say to myself, when I watched you teach, “boy, I want to be a good teacher, like Annie. I want to know the right things to say at the right time, to keep people motivated to keep on going forward.” So that was always like my thing. Really looking at the person and saying, “wow, I would have never thought about that.” I would take that, and learn from that situation. And there have been times when I’d go back to Baba Chuck, and I saw things sometimes where he got really angry and couldn’t control his temper, and even Khalid [Saleem]** said one time to Chuck: “Why are you going off on Sherone like that?” And he’d be like: “I don’t know. I think I didn’t have my B12 today!” [laughs]. I think that’s a slightly different situation especially when it comes to the issue of someone running a company. Being somebody’s mentor, their Baba, and also being in control of the company. It’s three different hats to wear. And I think those are hard hats to wear…to have the ability to move easily through those categories without having to feel like you are disrespecting one or the other.

AD

When I listen to you say that, it’s almost like saying the expectation to be a Baba or mentor is that you have to be perfect. I was thinking about the moment I realized that I had a lot to offer. I began to understand that I only truly got to know people when I let myself be seen as vulnerable – when I did things that maybe I wasn’t proud of, or I could have done differently. I think back when I started teaching you, I didn’t feel like I knew what I was doing. But, you know, the day that I left teaching, I still didn’t feel like I knew what I was doing! [laughs]. I just felt like I was more comfortable doing it. I was more experienced, but I wanted to treat everybody that walked in the door like I hadn’t seen them before. So in a sense, it was always not really known. It was just a little more comfortable. I hear what you’re saying too with [Baba] Chuck, or with people that have that title. There’s a responsibility with it as well. And how do you balance that responsibility with being human?

SP

When I walked into a lecture situation here at Appalachian State for the first time, and I saw those 50 people, I left after that first class and said, “what am I gonna do?” [laughs] Then somebody had to remind me: “Sherone, you know so much more than they know. You really don’t have to be afraid.” Then, I really had to trust what was already inside of me…the things that I have been taught and that are instilled in me, that I knew already. I always talk about having a living history in me of the people that have shaped my life. When I’m creating, my mentors’ voices and my friends’ voices start to come to me in my head. What I hear coming out are your voices, more so than my voice coming out. This thing that I had been listening to has now formed its way inside of my body and is coming out in a way that actually makes sense.

AD

It’s become a part of you.

SP

Yeah.

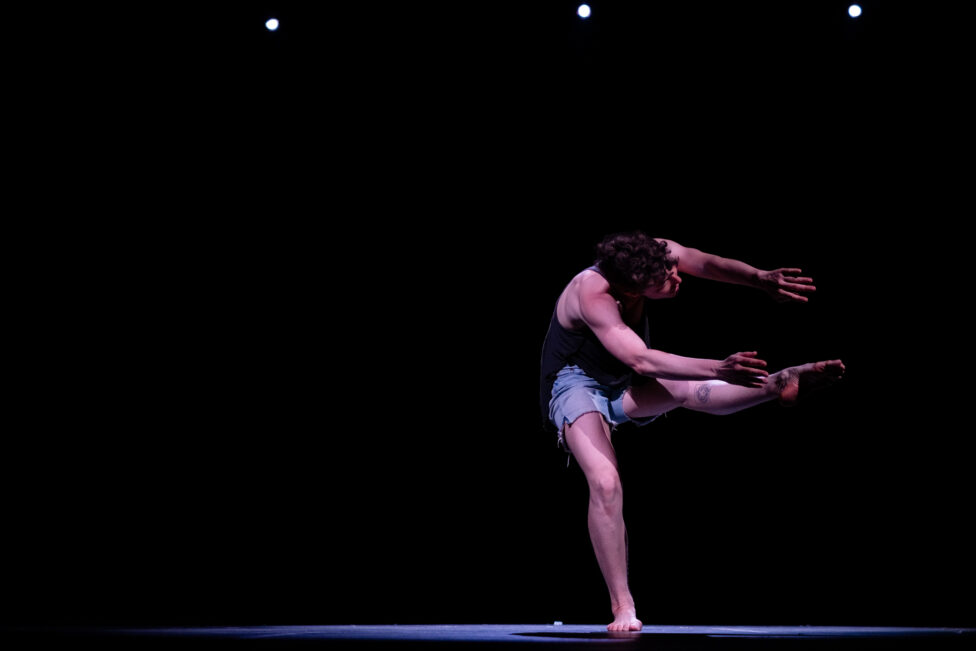

Photo credit: Anna Maynard

AD

I can remember you giving me advice back when you were in highschool. Here we were at Northwood [high school]. The administration had given us leotards, tights, and bars that the students thought they walked on the top of. It was a whole different vocabulary for everybody. I felt similarly to you. I was afraid I wasn’t going to have enough to really take them somewhere. What you always had as a student, and I think have as a teacher, too, is a quality of presence that meets the energy of the person that’s coming up to you. And that is what has brought people into it… It’s that you’re into it. And you have a presence that says ‘you can be into it too.’ That’s a rare quality to have in a teacher consistently over time.

SP

Thank you.

AD

It’s why I’ve always felt like I’m learning [from you] too. Plus, I can’t tell you how much being your friend has taught me and [provided] a little window into what it’s like to be of color in this world… what it’s like to navigate different situations. You have that graciousness when you do it that I’ve always respected. You’re honest about how something might feel to you. I think those are things with a mentor or elder in the dance world that I might not think of initially but they’re all parts of the person. When I observe how some people become elders, it seems they separate themselves from the people they mentor or teach. They make it clear that they know more than I do and it’s by distance that they establish it, rather than by proximity or closeness, which is very different.

SP

I totally agree with that. I think you taught me, when people ask me questions about certain things that I probably don’t know much about, to just own it. You said: “Sherone, you don’t have to give people the answer right then. You can say I’ll get back to you.” Most people who consider themselves mentors, and are high on that, would totally make up something and hope that you believe it. ‘You deliver it, you own it. If you don’t know something, act like you own it anyway.’

AD

It doesn’t make you less not to own it.

SP

Exactly. Sometimes it’s more meaningful to show the vulnerability that you don’t know everything because we can’t know everything. As I work with my students, I talk about the Sankofa bird… in order to move forward in life, one has to look back at the past to see what has been done. I think of that as a real true kind of statement. As I move forward, I keep looking back at what I had, at other people who I know who have done those things before.

AD

Also, sometimes you can have something stored in you that you don’t realize you are influenced by. I always felt, maybe it’s weird to say, that in mentoring somebody and being available to them, one of the things I need to be able to let them see is that you can be not just vulnerable, but you can actually mess up, and go back and fix it. Your integrity comes from how you handle what happens – it’s not that things don’t happen to you. Just because you’re a mentor, it doesn’t mean that you’re above things. It just means that you are at a place in your life where you recognize that what’s important is that things get resolved. That you get right with yourself, and that you get right with anyone affected by your choices.

SP

When teaching I often say, “take what I’m saying with a grain of salt. You can use as much of it as you want or don’t use any of it at all. It’s your choice. It’s your work.” It’s giving the student the opportunity to make some executive decisions about their work instead of actually choreographing for them.

AD

Well, and realizing that they have a reason for why they’re doing what they’re doing choreographically. And that their reason doesn’t have to be the same as yours would be. I think with creativity it’s really tricky because you want to give them permission to just go. At the same time, you’re asking them to reflect. I think if you can give the power to the person, nine times out of ten, they’ll do something amazing with it. More so than if I took control of it – they would just look like me…the respect I earned didn’t always come particularly from what I could do, it was what I could get them to do. I wasn’t always superb at what I could do.

SP

Does that change? When we don’t have the body to do what they want us to show them? In regards to the issue of eldership?

Photo credit: Tommy Noonan

AD

For me, I don’t want to say I’m gifted but, I think I’m successful at the things that I can teach about the body because I understand it in a way that I didn’t [when I was younger]. Through verbally describing movement and creative ideas, I know how to help somebody do certain things. I’m not necessarily the person to take technique classes from anymore because I don’t have that capacity to demonstrate physically a lot of the time. But I think it’s interesting to realize you have something else to offer…

SP

The issue of physicality and age…[there are] things that I wish I could still do, that I know my muscles won’t allow me to do, but I still have the love for. I still have the passion for teaching people how to do it, even if I can’t do it myself.

AD

One thing that I’ve always enjoyed is watching you on stage because even if you’re just shaking the shekere,*** you’re having a good time. It was such an honor to have you come play in that alumni concert, and have that feeling of exuberance… it’s out of age.

SP

Honestly, that whole show was just amazing. So many talented dancers, choreographers and musicians.

AD

It was magic.

SP

I agree. And that’s the big word, Annie. Maybe, the whole thing that we’re really reaching is that mentorship and eldership can’t be anything without the issue of magic. Honestly, the magic that we make when we are really into what it is that we’re doing to create something that’s beautiful, touching, rewarding at the same time. Sometimes we use the word magic, people are like, “what do you mean by magic? There’s no magic here! This is a skill.” I say no, skill is different. People can have the best skill in the world, but they’re not magical on stage performing.

AD

It’s when you can transition to a different reality for a time and space, or be so present in the moment you’re in that it transforms it. So how does this magic that we’re talking about relate to being a mentor or elder? I think mentoring or eldering is about noticing, cultivating and naming that magic in someone else. Titling it for them, so that they start to believe it. It’s saying ‘I see it in you. I see it in you and I celebrate it.’

SP

Yeah.

AD

Maybe it is magic. I guess that’s why we keep doing it.

SP

The magical part that makes what we do so beautiful is that dance is an art form that is always changing but you can’t duplicate. Each night is not gonna be exactly the same. Every single time you perform it, it’s a new experience.

AD

And it’s not going to come around again. We always think about that part of wanting to be present, don’t miss, don’t miss it. Don’t go out on stage and not have taken a few minutes to think about what you’re going to do because it’d be over before you know it. And other people might like it, but you didn’t get to feel it. You didn’t get to have that rush.

I mean dance is life, how you do your dance is how you do your life. I really think so.

Footnotes

*Baba Chuck Davis was the founder of the Chuck Davis Dance Company and DanceAfrica in New York City, as well as the African American Dance Ensemble in Durham, NC. He taught at many schools, universities and dance festivals throughout his career. He was also the recipient of numerous awards, and could get an entire opera-house-sized audience on their feet meeting their neighbors, dancing, and repeating in call-and-response (complete with accompanying hand gestures) “Peace! Love! Respect! For Everybody.”

**Khalid Saleem is a percussionist, musician, performer, accompanist, arranger, and teacher. He has taught African drumming and accompanied Modern and West African dance classes as a faculty member at places such as the American Dance Festival, SUNY Brockport, Appalachian State, and Duke University. He was also the former music director of the African American Dance Ensemble, and is an acclaimed international performer and educator.

***The shekere is a West African percussion instrument made out of a dried gourd covered in beaded netting.