Millie Kapp: I have a lot of faith in these conversations and I am interested in your impressions, and to know where things landed.

Kyle Dacuyan: The first impression for me is balance and it was an organizing principle throughout. The balance of objects, of objects on top of other objects, and the precarity of that. The tension of things falling or not falling stayed throughout the piece. And then the inverse of that as well, through the construction of things staying together, of finding assembly or equilibrium. I also noticed a lot of SPLAT. Another kind of adherence.

Matt Shalzi: We have talked about words and their stickiness and their adhesions and that was something that we were really focused on. And, we studied a scene from the original Dracula.

KD: That created a stand-off quality, which is another balance.

Georgia Wall: I also observed this stand-off quality in all three parts. In the first it felt like parent to child, sibling to sibling. A comic book representational of those archetypal relationships. Narratively, the stand-off went seemed to go from being between the two of you to each of you battling something internally. I was thinking about how when we are in relation to someone and there is a stand-off there is also often an internal stand-off, an internal landscape of not quite knowing where to go or what to say or what to not say. The internal standoff arises from negotiating your own maze of thoughts and emotions. In the third part the stand-off shifted so there was a space between you but in that space there was also support- like you were supporting another by literally shining a light on the other person, standing away from one another. Something changed.

Chris Domenick: I saw a beginning, middle and end as well. In the beginning your bodies are in relation to one another and the objects, in the middle your body is isolated, and in the end your bodies are constructed by the other bodies and objects. Your bodies are a part of the menagerie of objects.

Gordon Hall: I am wondering what interpretative frame we should be using. I don’t find it helpful to try to understand this work’s narrative and to try to understand it symbolically, and to try to understand it as the two of you as singular individual characters. It all shifts so quickly, in the same way the props have all of these different and very satisfying uses and change with the way you employ them. Your bodies are operating similarly, and so are your characters. I wrote down “they are not singular beings” and that was helpful. I stopped trying to interpret the symbolic meanings of your actions. I started thinking about it sculpturally in terms of how objects relate to one another. I wanted to ask what sort of interpretation you think about or want, or is there a way you talk about your work while you are making it? Is there a narrative arch? Do you have singular characters that are evolving over the course of the piece? Is your body yours? What is its relationship to the objects?

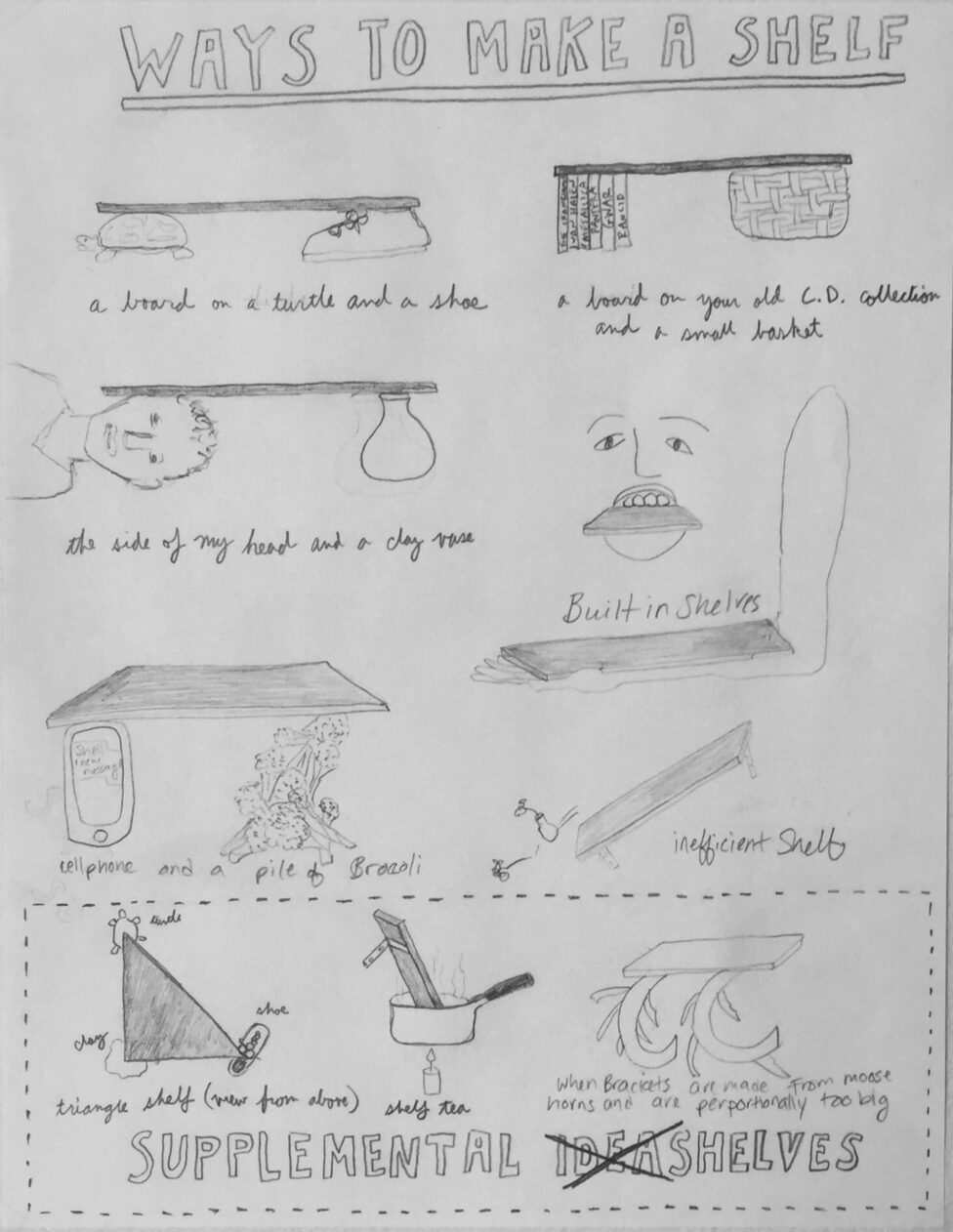

MS: We were talking about how the shelf in ones house is something that holds cayenne pepper and salt and potatoes and a photo of a dog and next to that some incense and a trinket and more simultaneously. There are some things that are constant, there is always a spot for the picture of the dog. But the salt is getting replenished or it is a new season so you are putting limes there instead of potatoes. I think of us as shelves. We can hang these different objects, that are all metaphorical, on and off of us, changing all the ingredients quite rapidly. It is a period of intense curiosity. We are learning by shifting and becoming and using. We are watching a movie and I am hungry and we are hot, but then I ate an apple so I am no longer hungry but we are still watching the movie but now my knee hurts… so that is a new arrangement. It’s a constant shift of combinations and adherences. We move through the work like this, shifting what is next to what.

MK: I’m attempting to create scores and situations for trying on and off selves rapidly. That is what it is about for me, it is about a change or a dense web of shifts. The work is formal while simultaneously being obsessed with what’s obvious and known. I want to create performance that lives in that state continuously.

MS: The way we make work is related to how we respond to work. Millie and I call this “creative response,” which is a process we learned from former teachers of ours. Depending on what work we are seeing and how it sits with us, this creative response can take many rehearsals to develop or happens instantly. Interpretation comes in the form of making…a way to live in the response and not be separate from it.

MK: We are interested in the audience having an experience, an emotional response to the work, a journey that holds the audience in a state of familiarity and abstraction.

CD: Wondering how we are meant to think about characters is almost a moot question because that is the question of the whole piece, the whole piece is about code switching. Your interpretation of something quickly shifts from utilitarian to symbolic to intimate to splat. It switches so fast between these significations as it moves through your body. The foundation is constantly called into question and that is one of the things that is successful about the piece. I am asked to constantly shift the lens of understanding the very thing that I am trying to understand.

GW: There is so much facial information. Your faces undergo so much transformation and I realized I connect face to thought. When I am watching you move, it felt very language rich. Your solo dances are like monologues. Bodies and objects are being used like words.

RJ Messineo: Your characters were multifaceted and singular. It was built around a singular subject who was more than just one thing. The relationship between the two of you was also a subject. I also saw gender playing out. A navigation between male and female or you say something and then I say something or you do a solo and then I do a solo.

Lydia Okrent: I was thinking about conflict inside of cohesion. In the first part, your faces matched the activity and this made a narrative or a potential narrative stand out in a really trope heavy way. But as things started piling up, as objects started to adhere to places where they don’t belong or get used in ways they are not “supposed” to be used, the literal started to unravel. Objects and moments coalescing into new configurations because of the objects and your bodies being in conflict but adhered. I was not trying to track anything as everything disappeared the moment before I could name it. This is a really lovely place for me to be as an audience member. Being allowed to take part in or give in to the delightfully illogic. It takes me away from asking why something is happening.

GH: I did a lot of thinking about emotion and your faces and sincerity and irony and horror and slapstick and humor. The acted emotion changes so quickly that I don’t feel anything in direct response; I don’t feel happy or scared or worried. I am feeling a lot of emotions about other things like a sort of wonderment over what happens when you just follow an idea to its end. I am baffled in the best way. I wonder what your faces are doing to the work, what would be different if everything was the exact same but your faces were neutral.

MK: The face is a tool that is stereotypically underutilized in dance. We are interested in getting at a movement state that refers to something and then doesn’t and that is something the face can do.

LO: I found it jarring when you weren’t actively using your face. When you became natural. Or less than neutral, self conscious.

MK: We have thought about this question a lot. When the face is used as a signifying tool and then you try to take it away, it is really confusing.

LO: You can’t ever take the face away. It’s always going to be there on the front of your head.

KD: I watched your faces less as something evocative of emotion and more like part of this whole terrain of moments that have different consequences. I was also tracking your faces as one person registering a shift in how an object is being interacted with. The moment I noticed most was when Matt was crinkling the cans, and your face registered that as “I hear something is happening with the cans and I am going to move in a way that is responsive to that new atmosphere that is happening.” It was less like, here I am going to use my face to make the audience feel a particular way about my internal state, more like we are working together facially to make agreement about rules or environment we are going to be working with.

GW: They’re masks. They’re not you. You aren’t saying this is me.

GH: We are hardwired to respond to faces emotionally. When you are speaking to somebody and they are making facial expressions, you don’t really have any agency around how you are responding. A little bit goes a long way. Your facial expressions are not expressing emotions in a standard way which I am excited about. It’s a very weird feeling. Maybe just think about that more and play with what it is to produce emotions that are not expressive.

MS: Do you think that applies to just the face? Or if you use your arm a certain way it leads to a certain set of consequences. Or are the consequences of the face more than the consequences of your genitals your big toe your knee? There’s a hierarchy of consequence in the places at the top.

GH: When we watch dance, bodies are moving and we are responding to what those bodies are doing. The face has a particular power, and not just conceptually, to effect the emotional state of the people observing. It is a powerful tool. There were places in this where it maxed out and I couldn’t engage.

LO: I think you could have more dexterity. It can be subtle and still as evocative. Apparently babies are having a hard time relating to their caretakers that have had botox, the micro movements have disappeared and those micro movements convey so much. I’d be interested to see a bigger range between the pantomime of “evil guy” and a more “neutral” face.

GW: I think there were two or three too many objects. The magic is this returning and repurposing and finding every possible way to use the thing. I got maxed out on the magic of the objects because it was like if you need it, it was there.

CD: I was thinking about a hierarchy of gestures and objects. What gestures am I engaged and mystified by and which gestures do I just read really quickly. There is a line drawn in the sand where viewers on one side are excited by deconstruction and reconfiguration, and the viewers on the other side feel they are manipulated to where it feels oppressive or untrustworthy. There were a few things that I was skeptical of, like the licking of the screwdriver and the going out the door. I don’t know if that is a completely subjective read or, that you pushed me too far as a viewer and I can’t trust that I am still on the magic carpet with you.

LO: I felt similarly about the screwdriver. You did what I would have done. It lost the bewilderment, I felt myself catching up with you.

GW: When I was thinking about what I would take out, it was the screwdriver. It is already something that is used to produce, its function is too apparent.

GH: But it is being used for everything other than what it is supposed to be used for.

MS: When we make work there are moments where we find ourselves acting out the obvious. The gesture of licking the screwdriver is one of those moments. It feels important to include these kind of acts.

MK: Maybe it’s about where it comes In the sequence. The beginning there’s these sort of tropes that are super established and then start to disintegrate. It’s about context, what comes before and what comes after. Going out the door, given the madness of that middle section, it is maybe not where it should go.

CD: In no place in the piece do I feel like you guys are losing control. There’s this real element of prowess and expertise around the movements. There’s no moment where I am left to lose it or watch you lose it. I was thinking about that during the solos which I felt we’re really about this type of physical, gestural, and theatrical prowess where you have the ability to incorporate and utilize all these different communicative tools with utter confidence. At what point does it get to a place where you lose a sense of control and like what does that look like.

GW: What does losing control look like when you’re already so out of control. You can’t have an explosive solo dance that looks like you’re out of control because you’re already doing that. What is really outside of this world?

GH: I have no desire to go outside of this world. There’s a tension in the whole thing. You created a universe that is so tight, to me that’s captivating. I actually don’t need to see you lose control. It’s a performance, no one ever actually loses control, it’s always a pretending to lose control. Your super uptight world of objects that you’ve made is a Polly Pocket where everything happens inside. Everything is exactly where it needs to be in order for the performance to work. It is obviously all planned out. That is really satisfying.

LO: When Millie chuckled, when you laughed at whatever it was that Matt was doing, that was, in a sense, a loss of control. In that it wasn’t planned, it was a response to the current situation, in real time. You lose control of your controlled performance, that’s what bodies do. If you step on the clay, or forget the cherry, or unexpectedly find what the other person is doing is funny and respond, then it is a peep into the moment, into the fun you are having, it is revealing of the matter behind the artifice of the performance.

CD: In terms of the idea of control, obviously the representation of being out of control, that was not the idea. I wasn’t looking for that. You’ve created a situation where whatever happens gets absorbed and comes apart and that’s such a success of the piece. I think about control in regards to your process. And it seems related, like to the licking of the screwdriver. I don’t know how to articulate the relationship between those two things but they are tethered. The idea would not be to eliminate the licking of the screwdriver, but rather how do you restructure an understanding of the licking of the screwdriver in such a way that gives the viewer a step into not reading it as flat-footed.

LO: It is also about spacing and timing. You both licked the screwdriver downstage right and the door is stationary so that action happened in the same place each time. I could probably do a pretty good job of recreating both of those moments. It became a more solid image for me. It stuck.

GW: Why does this world need a screwdriver? Even though I know that is an absurd question.

RM: The screwdriver needed to do something very specific that only the screwdriver can do in this world. I was weirded out by the turtle. It’s the third being. That’s not a toy turtle, that’s a real turtle. At first I thought it was alive. So then I am distracted by this dead turtle. The turtle is the pet, the turtle is the baby, the turtle is the project, the turtle is the thing we are worshipping. It has or had some kind of life, that doesn’t give a shit about this world, if felt like an unwilling participant where nothing else had that coerced feeling.

MS: We became interested in some turtle mythology and then we went to Millie’s grandma’s house and heard this story about her grandpa finding a snapper in the front pond and they ate it and saved the shell and shellacked it. I’m renting this taxidermy turtle from a friend.

GH: I’ve only ever seen your work presented in performing arts setting where the props are in the work and then they’re gone. What would it be like to exhibit it in a gallery setting where the objects could stay and people could see them close up? Or what will happen when the audience is larger and everyone is far away because of the larger space and then they lose the details of the objects? How does this scale up or interact with different kinds of audiences and spaces?

MK: It is an interesting conundrum. Making art in New York more often than not I find myself making in really small studios and often showing in tight spaces. We’re fitting ourselves into a condition. Matt and I made a performance last summer for a gallery and a few months later we tried to show the same work in a theater and it lost something.

GH: I want you to be empowered to say this is what we do and we want small audiences so no matter what you will limit the amount of people that are watching. Your work is growing in these certain conditions and it is totally within your rights to insist on those conditions.