WeisAcres, located in a historic Soho co-op at 537 Broadway and home to a stable of seminal choreographers and visual artists for the past four decades, has recently re-emerged as a space for performance and communion with Cathy Weis’ Sundays on Broadway series. I recently sat down with Cathy to discuss the trials and tribulations of loft living in today’s New York City within a space that reveals itself upon entry as a historical pocket in time. “Reading the walls,” Cathy situates her projects within a context that spans her extensive library of archival film, current choreographic pursuits, and technological, performative objects. Comprised of both live performance and screenings of archival footage accompanied by lectures by related artists, notable in the upcoming Sunday on Broadway program is a marathon screening of 9 Evenings: Theatre and Engineering, a performance series that, in 1966, paired artists and scientist and engineers for a run of events at the 69th Regent Armory. 9 Evenings includes performances by John Cage, Lucinda Childs, Öyvind Fahlström, Alex Hay, Deborah Hay, Steve Paxton, Yvonne Rainer, Robert Rauschenberg, David Tudor, and Robert Whitman.

____________________________________________________________________________________

Cathy Weis: I was born in Kentucky and moved to this big, bad, dirty city in 1983. In the 90s I would do evening length shows, at the Kitchen, DTW, PS 122 etc.—one every year—shows blending performance and video. Then for various reasons it became harder for me to drag around all that video equipment, so I needed to find a place to work. I looked around and couldn’t find a place. Simone Forti told me she was going to sell her loft; moved to this building in 2005.

Biba Bell: How long has she had this place?

CW: Well, this is a very interesting building. In 1975, George Maciunas, a Lithuanian artist, got together two groups of artists. One group bought this building for $325,000 and the other group bought the one next door. Back when it was built in 1868 this [537 Broadway] and 541 were all one building. Then, at some point, it was divided down the middle into two co-ops. This was an industrial zone and the light industry was fleeing the city so they could hardly give these places away. This one was an old sewing machine sweatshop. Davidson Gigliotti, one of the original people here, said that when they got this place there were sewing machine needles in the cracks between the floorboards. This building extends all the way through from Broadway to Mercer. The choreographers all favored the Broadway side of both buildings: Trisha Brown, Lucinda Childs, Douglas Dunn, David Gordon and Valda Setterfield on that side. On this side was Elaine Summers, Francis Alenikoff and Simone Forti. Jean Dupuy, a performance and visual artist, was also on this side. He had the smallest loft. On the Mercer Street side were the visual and performance artists: Joan Jonas, Jackie Winsor, and some others next door, and Nam June Paik, Shigeko Kubota, Ay-O, and Yoshi Wada in our co-op. Some of the original people are still here; Shigeko Kubota and Mary Beth Edelson, Elaine Summers and Davidson are still here, but in a different loft.

BB: That’s some company.

537 B’way in 1910

CW: Only artists could live here, they all had to get certified by the Department of Cultural Affairs. George Maciunas developed eight buildings in SoHo. They all became A.I.R buildings. These two were his last ones. He was a founder of the Fluxus movement and all the people in this building were closely associated with Fluxus except Elaine and Davidson and Mary Beth. It was a Fluxus building. It has an amazing history and you can read the history in the wall. I’m doing a piece on this— reading the brick wall. You can see traces of the building’s past if you look carefully. Here’s where Simone had a wood-burning stove… you can see over there by the two arches. There’s a big courtyard because the building was built before electricity and they needed the light. They heated with coal during work hours only. When the artists moved in they found a coal bin with about a half-ton of coal. They also had an incredibly old open car freight elevator on the Mercer Street side that they continued to use until 90s. It was very dangerous. This building was never meant for living.

BB: Is that especially challenging?

CW: Yes, it’s a big problem, heating is very uneven, and before we put in new windows it was beyond drafty. But it’s such a fabulous place to live. And now, over the years, this incredible retail district has built up around us and it has become very valuable. It wasn’t back then when they started.

BB: Absolutely. Do you feel like the role of artists at that time also became an impetus for the shift in terms of real estate? Did it add value to the neighborhood?

CW: That’s always the way. First the artists and then the rich people driving the artists out. After that they don’t give a shit about artists, really. Real estate value down here is all about money, commercial selling, stores, women’s clothing, expensive lofts. That’s where the money is. They don’t care about artists; there’s no money there. Especially dancers, we know that.

BB: Okay.

CW: Most of the artists now are in Brooklyn, not here. Except for the older artists. It’s pricey, everything. Even just getting lunch is pricey. It’s all tourists. You go outside and it’s like being in a mall.

BB: It feels like this building and this co-op is like a time capsule, an island in time.

CW: Oh, definitely. But who knows what will happen? There is pressure as it becomes more valuable. And artists can be just as hungry as everybody else when big money comes along. But this building has an incredible history in terms of artists, with Fluxus as a centerpiece. Even now, downstairs is the Emily Harvey Foundation. Davidson, one of the original people, is the president. They have a big Fluxus following, people who were involved in that movement. It’s an older group. They do a regular exhibition and performance season every year.

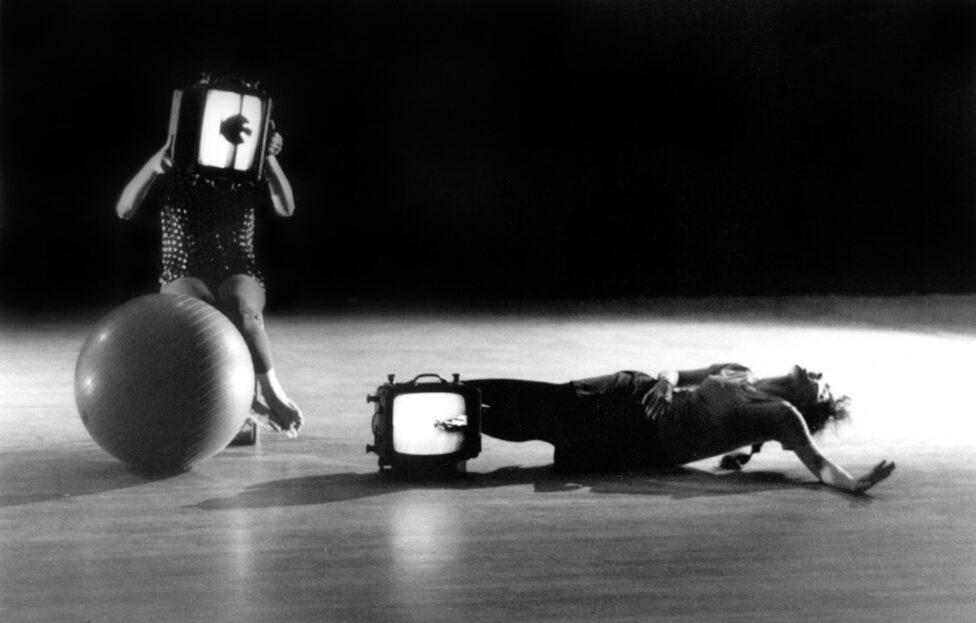

Electric Haiku, 2002. Cathy Weis. photo: Richard Termine

I first moved in here because I wanted to work. A number of years ago, I started a Salon Series where I had small invited shows because there aren’t so many places where dancers can really show work in New York. These kinds of places used to exist all the time. Dancers had places like this where you’d go with friends to see what they’re working on and talk about it.

Electric Haiku Calm As Custard, 2002. Jennifer Miller & Cathy Weis. photo: Richard Termine

BB: Dancers had their own studios.

CW: Yes, they did. Choreographers needed a place to work so they had studios. But you can’t get that anymore without a lot of money. Back then you could if you chose to live in rougher situations. Trisha said when she was first here it was like the Wild, Wild West. There were no rules and you could do whatever you wanted because nobody was down here checking on you. Anything you thought of you could do. It’s not like that anymore. That’s how things change in New York City. It’s always changing. Did you read Carolyn Brown’s book Chance and Circumstance: Twenty Years With Cage and Cunningham? I love that book because it was really a dancer trying to understand what it was that kept her engaged. She was trying to understand what it was about dance that made her continue and what she needed from it. In the ‘60s you could go downtown, you could live and friends would help friends and you didn’t need much.

BB: Yes, her stories are so vivid about that time.

CW: She let us know what could be done in that environment. This is a different environment. The whole country has changed—it’s not just New York. People’s attitudes about dance are completely different. There’s no hunger for it. People have become isolated and detached; they don’t have any connection. But at that time it was different, Steve Paxton could come from Arizona to New York without any money and live and meet people like himself, it was exciting.

BB: It’s hard to imagine those kinds of opportunities for young dancers now.

CW: It was much freer and there were many more opportunities in that way. Now all the young people I know have to earn money. That means time, so you don’t have the time to hang out and look at things and the spaces aren’t there. That’s really why I wanted this space, to have a place where people could look at things and talk about dance, a place that used to be everywhere and also a place for me to work. I wasn’t just being generous; I wanted a community that would be strong. That was my intent. I moved to New York in ’83. I was doing video, not dance. That’s a whole other story. But from 1993 until 2005 I choreographed a major show in New York every year.

Electric Haiku, 2002. Scott Heron. photo: Richard Termine

Then, when I bought here in 2005, I invested everything I had and everything I could borrow and scrape together. Simone was very generous. She didn’t get as much as she could for this, but she wanted to keep it in the family so we made a deal. She wanted to buy a place in LA for her family. We didn’t have a broker and did it between us cutting out a lot of red tape and expenses. We were able to do this deal and it was a lovely thing. But I had no idea what I was getting into. The Board here, mostly people who were not the original shareholders, didn’t want to let me buy because I had MS! I got a lawyer who convinced them that this was a very bad reason. Then once in, I didn’t know I was moving into a nightmare. But I should have had a clue.

BB: Why is that?

CW: Some day I’m going to do a piece called “How I lived in the meanest co-op in New York City.” It turned out to be rough going. But everyone has horrible tales of their co-op experiences.

BB: Oh my god, I’m so sorry. [both laugh]

CW: It was just insane. There was one couple that really worked hard to make life difficult for me, and they had friends. Fortunately they’ve moved on. Also our building manager at the time of my move is now serving time for embezzling money out of the co-ops that he managed.

BB: That’s no good.

CW: I’d never been around such people before. I couldn’t believe that with proper discussion we couldn’t just work things out. I’ve learned a lot since then and it helped me understand what a mess the world is in. People don’t compromise and don’t have empathy for anybody else. I want somebody to write the story about this coop; maybe someone that’s seeing this now will want to write that story because it could be an HBO series. It’s perfect for that! It’s got intrigue, backstabbing, artists, sex, everything you want!

BB: It’s very sexy.

CW: Totally sexy. New York artists… big money!

BB: Bravo Television.

CW: Oh, it’s perfect.

BB: So you entered another world…

CW: Another world, and they made me president right away. Nobody else would do it. But within a few years we had a million dollar lawsuit and were being investigated by the Manhattan District Attorney’s office.

BB: Did that stop you, were you able to work?

CW: I’m only just getting back to work now.

Sundays on Broadway poster

BB: Is this series, Sundays on Broadway, the beginning?

CW: It’s the beginning.

BB: Have you wanted to do this for quite awhile?

CW: Planning for it. The whole reason I went through all that was to keep this place so I can do stuff like this. I gave up a lot, but I got a lot. Things are smoothing out. I’m still president, by the way.

BB: And you can continue with your life?

CW: I can continue.

BB: Congratulations on entering this next phase! What a relief.

CW: Yes, this is just the beginning of the next phase of what I’ve wanted to do all this time.

BB: So right now, did you start off with a screening of 9 evenings from the Armory?

CW: We started off in the Spring with Julie Martin. I asked her because I knew her and I was interested in this series that she did. I asked her if she wanted to do some screenings here, so we began the series that way. We started the first, David Tudor, which was fascinating. You know about 9 evenings?

BB: A little bit.

CW: It was in 1966 at the 69th Regiment Armory on 25th and Lex, a huge place. It’s the armory where they did the big Armory Show in 1913. It was an Art and Technology event so it was a big to-do. They hooked up artists with engineers from Bell Laboratories.

9 Evenings, 1966. Robert Rauschenberg. Video still.

BB: I remember the Bell Laboratory connection.

CW: Julie said that when the engineers asked the artists what they wanted to do, they all just wanted to fly. But they did incredible things. David Tudor is one of my favorites. The armory is so big and when you say something the echo has a six second delay. They thought dancers couldn’t dance to the sound.

BB: Because the sound is throwing everywhere, echoing?

CW: Yes, it’s completely lost and it comes back way after. Of course, for David Tudor and John Cage that was a huge advantage, something that could be fabulous to play with.

BB: It was difficult for the dancers because…?

CW: Well, it was their first spontaneous reaction. The musicians, the experimenting musicians seized it. I think a good improviser seizes the problem and makes it an advantage. David Tudor made the whole place an instrument. He had little platforms that captured sound waves and threw them out and multiplied everything. He was making a cacophony of sound that was building and building and building by playing a bandoneon into some kind of complex system that controlled lights, video images, and moved the sound around the space. Great. Each evening was totally unique and it’s fun to go through them because there are some people who were there, like Mimi Gross. I don’t know if you know her. She’s a wonderful visual artist. She does a lot of work with Douglas Dunn, and she was there in ‘66. Billy Kluver, who later married Julie Martin, and Robert Rauschenberg got all the evenings filmed. Julie is still editing the films. There are interviews with people who were there, talking about them now. When we play the film we also try to get somebody who was there to come and talk about what it was like. Fascinating.

9 Evenings, 1966. Robert Whitman. Video still.

BB: So, you’re really producing, continuing to produce and add to the archive around these works by hosting these evenings.

CW: We did David Tudor first, then John Cage, then Deborah Hay, then Oyvind Fahlstrom, and then Robert Rauschenberg. That’s what we did here in the Spring season. This fall we have Yvonne Rainer, Steve Paxton, and Robert Whitman. Two more events will be Alex Hay, Lucinda Childs. In January, we are going for a marathon and watch them all.

BB: That’s great. I’m going try to come into the city for that.

CW: Last weekend, we watched Paxton’s evening. Afterwards we Skyped him and talked to him projected on the big screen over there. It was great talking to him about what it was like. He’s not the first one but he talked about how hard it was because all these artists had been downtown artists performing for their friends and people who understood what they were trying to do. It was like a science lab downtown where people were investigating movement. Suddenly they had this huge event at the Armory. The whole city, thousands of people, in a huge, huge place with lots of equipment, high tech stuff from Bell Laboratories. One obvious thing they did that made things harder was having two productions by two different people every night! To take it down and put it up again, it was crazy! Yvonne said she got really sick because everyone was working nonstop around the clock and things weren’t turning out right. It was down to the wire, no one knew how it was going to work. She said she wasn’t eating, she wasn’t sleeping and finally she had to be taken to the hospital because she got so sick. Steve said the same thing—that it was very stressful. After 9 evenings, he said he quit group work; he suddenly found solo work very alluring. You make mistakes when you try something new.

BB: It creates a huge juxtaposition to imagine people working in spaces like the loft here, a live-work space that’s a studio that also feels like a home—it’s intimate, it’s personable—and then to go to a space where the scale changes massively.

CW: You’re showing work for your friends who have similar aesthetics and then suddenly you’re showing it to uptown people who have never seen anything like this and don’t think it has anything to do with art. It was very intense for everybody. You know, these films were cut to twenty-minutes, interviews for twenty minutes, when the actual event really was more like an hour and half. You can make a lot of stuff look good if you cut out all of the bad parts.

BB: A good editor can!

CW: A good editor does wonders! I asked Mimi, “Was it like that from your memory?” She said, “Oh no, it was such a boring time! Nothing was going on, everyone was waiting and waiting for something to happen.” Meanwhile, the performers were frantic. They were trying to get the thing to turn on and everybody in the audience is just waiting.

BB: Wow, yeah it does sound a little stressful.

CW: It sounds great. It was so raw, people were taking chances! Nobody had ever done anything like that. They didn’t know anything about it. There were big mistakes… all the stuff that one has to expect if you really take chances.

Technology and artists came together for the first time to try something new. It was very exciting but also had failures which you had to have. Now there’s no place to make big failures. Today you take off your clothes and people think, Oh they’re doing something unusual, or repetition, doing the same thing for an hour… but it’s been done many times, it’s really quite safe. That’s why I want to have this place where I can try things and it can be dumb or doesn’t work. Now, you do one show a year in a big place and it better be good because everything depends on it and the place has to get people in, they need the money, they need the audience.

BB: There is so much at stake in that single event.

CW: Yes, it’s got to be safe.

Electric Haiku, 2002. Scott Heron. photo: Richard Termine

BB: And you, yourself, have a major archive of your own video and performance documentation. Are you going to be showing that at during the Sundays on Broadway events?

CW: Well, my first love and interest is in live performing. That comes first on my list of priorities. As for my archive, I don’t know. I have a great archive. I’m transferring a lot and digitizing a lot of work but I’ve got tons more. I’ve got to clarify the concept of the whole thing before I start playing around with it. I’m not ready yet. I do want to do this one thing called “Look into the Past” with Madame Xenogamy. I may have a palm reader. You could make a reservation with the Madame and she’d take you back into the past to witness rare dances not seen in 30 years–Steve Paxton, Ishmael Houston-Jones and other mystic creatures–NYC downtown’s finest in the dance scene of ’83, ‘84, ’85…

BB: That sounds amazing.

CW: I’m working on that.

BB: Wow.

CW: I think that will be happening in March or April.

BB: Fantastic.

CW: Yes, I want to have a different way to view dance from the past and that has to do with my archives. But I don’t want to just show tapes in my Sundays on Broadway series.

An Abondanza in the Air, 1990. Lisa Nelson & Cathy Weis. photo: Lona Foote

I also want to make new work and to continue exploring ways to expand my own movement range by partnering video and technology with performance. We’re so used to the way we look at video or film; we’re all staring into these squares. In my performances both performers and video imagery move around and my frame is the whole stage, not just the video frame. But I know if I put media on stage everyone is going to be looking at the screen. How do you choreograph for the eye? I just taught a course at Sarah Lawrence called “When Technology and the Human Body Become Partners, Who Leads?” that deals with these issues. Also, this Madame Xenogamy, who looks into the past to find a different way of looking at dances.

BB: Almost as if it is a memory.

CW: A memory that you can look back into. But you asked about my archive. I’m trying to find a way of showing the pieces so that one cannot forget the context in which it was made was different than the present. Simone is a perfect example. Simone did a lot of stuff in galleries where you would walk around and it was very informal. You could see the bodies, they were right there. That was a different piece but how do you talk about the dances from the past, and how do you look at them? Back when Steve did a pedestrian movement on stage it was completely different from seeing a pedestrian movement now on stage. We’ve seen it a million times. Then, you hadn’t. So how do you do it? Maybe you can’t. Maybe we should forget about it altogether. But I think we can break the habits of how we look at things. To say, “Look, it’s in the past, it’s in a different context…”

BB: Making the context seem unfamiliar through a palm reader and the act of looking into a crystal ball seems to speak to the impossibility of revisiting this past.

CW: It at least makes you aware that it’s something else; it’s past.

BB: There’s no way to have this idea…

CW: You can’t have the same experience as when people saw it the first time. That’s true of every generation.

The Bottom Fell Out of the Tub, 2014. Cathy Weis. photo: Cathy Weis

BB: It’s a great way to comment on that. Your Sundays on Broadway series also includes live performance. I see you did a number of shared evenings.

CW: As I said, this is where my heart is… in the live performing. I’m starting with sharing one Sunday evening with Jennifer Miller, another with Vicky Shick, another with Jonathan Kinzel. In each, I will show something I am working on, they will show something they are working on, and then we do a structured improvisation together. I used to do informal live performances. When I was doing those big shows every year I had to give all of my concentration to that. It takes a year to get everything together. People, scheduling, the place… it takes a year. But I always enjoyed the opportunity to perform more when it didn’t have to be so precious and you could develop something with an audience and with people viewing it, not just in your head or alone. Performing becomes more integrated into a weekly practice. Even in a rehearsal you had time to adjust to people watching and make that part of the rehearsal. That was another reason I wanted to do this, to use this space for my own work, to get more information about it and to see how other people see it. It also gives me a chance to work with more people. I’m working with a couple of young kids but if I was only doing a big show I wouldn’t take a chance on people, wouldn’t have the time. Having a space of your own changes everything. To simply work with people, try things out, see how they perform and how they relate when they’re performing, how they improvise, how their imagination works when they’re moving, all the things that I’m interested in, allows me to see without having to be so safe.

When I was younger, my friends and I were all working together. Now that I’m older, everyone is doing their own thing; this is always true for choreographers. It took me seven years to get this space. I had to be in a place that was easy for me. I couldn’t go back and forth. I had to have a place where I can leave things set up and come back and it will be the same. I had to go through a lot to get this and I was lucky enough to have it work out. There were a lot of steps and it could have failed in a lot of ways. But it didn’t.

BB: Do you also want to be able to fail in your work?

CW: You have to be able to fail or you’re not taking a chance. Even so, I always try not to gamble too much now that I’m older. I gambled a lot when I was young, I didn’t know any better. But when I got older, I knew that it hurts when you fall. I try to take chances when I know I can survive the fall. Now this is a nice moment where something is coming to fruition. I think it’s just the beginning of what can happen here.

BB: Considering what you’re opening up to the dance community now, and considering all the resources and richness that you have both from the past and into the future, I don’t see how you can fail.

CW: Well, it’s a big world out there. They can always pull out the Uzi and chop you down.

An Abondanza in the Air, 1990. Lisa Nelson & Cathy Weis. photo: Lona Foote

BB: But it’s pretty incredible.

CW: I have a lot of work I did that I love. Last week I did a couple of old pieces, each about ten minutes, and then a new piece. Being able to keep old work alive is great, not just on a videotape but really having people see the stuff and also to try out new work. Not just all new, but both old and new. I’m not only interested in making a communal base, it’s also a laboratory for me. It’s something I want to investigate and I need people to do it with. I want to do it with people who are a part of the whole process. I want to make things with them. This is the time to do it.

BB: It sure is.