Anh Vo: So we discovered that we both had some sort of naïve, embarrassing political ambition as a child, teenager, young adults. Right? You said that, “oh, that’s why we were such great friends.” Do you want to say what your ambition was, and then I will disclose mine? [laughter]

Alex Tatarsky: Wow. Yes, it’s somehow a relief to get this off my chest, really. My secret shame! I mean, I was fully committed to becoming the first female Jewish dancing president. [laughter] And I knew this from a very young age with total certainty. People would ask me what I wanted to be when I grew up, the classic question, and I would just say, “Oh, I’m gonna be the president.” There was no doubt! I essentially began campaigning in 1997 or eight, and everybody knew. So someone made me T-shirts that said “Tatarsky, 2044.” Somehow, that’s what we decided: when you’re 54, that’s a presidential age. We had a logo—Tatarsky 2☮44— the zero was a peace sign. Grownups would say “this is gonna be a really hard job, you know, are you sure you want to do that?” And I was like, “oh, no problem. I’m so ready. How hard could it be?”

AV: Laser focus.

AT: I don’t know what happened, since then it doesn’t feel quite so… appealing. What age was political ambition for you, and what form did it take?

AV: It was much later, with some sense of certainty, but less straightforward. It was awakened when I left Vietnam. So like 16, 17, getting a scholarship to study in the UK at this wild school, which is called UWC. It was born out of the Cold War, like 1960. It has this idealistic vision of bringing different people from different cultures to work towards peace, and education is one tool for that. So we were like 350 students from 90 countries. There was a year where I was the only Vietnamese student.

I started reading about the Vietnam War; and combined with the political fervency in that school, it made me want to… it’s very embarrassing… But I wrote in my Common App that I wanted to get into Harvard, specifically, to then go into law school, to become a revolutionary, to become a history expert and use historical knowledge as a base to overthrow the Communist government.

AT: Wow, Anh!

AV: So there’s that trajectory, certainty, and clarity that’s similar to you. But it’s a little bit later.

AT: I was vice president of the Model UN club and that was very important to me.

AV: And what age was that?

AT: That was high school. I was constantly going to fake UN conferences and getting resolutions passed. At this time, it began to dawn on me that politics is, at least in Model UN, largely charisma: who likes you, who you can convince one-on-one with your rhetoric and your charm and your likability. In some way, it has informed my interest in stage presence and how energy captivates or doesn’t captivate. Certainly you can really monologue at the Model UN Conference, and inspire with your performance. But hearing what you were saying struck me in that I went to lefty, hippy schools that were formed with a sense of idealism about the possibility of change. And hearing you describe your experience in school, it just makes me think about their formation in the shadow of a certain historical situation and mood that feels so over.

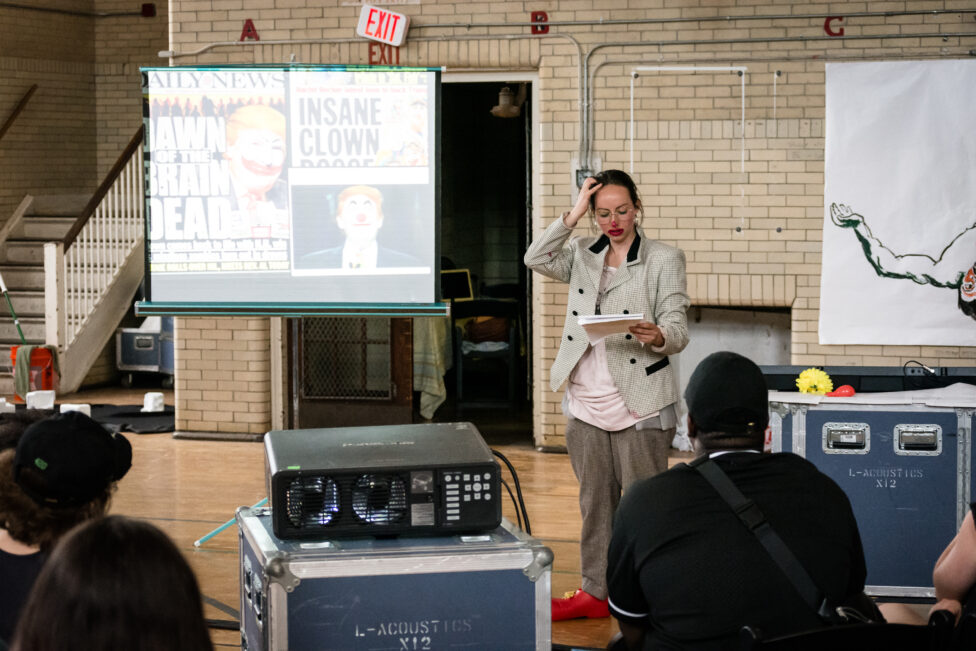

Photo by John C. Hawthorne

ID: With a red nose and red lipsticks, Alex delivers a lecture in front of a group of people. Projected in the back are press images of Donald Trump in clown makeup.

AV: It’s true. There’s no coincidence that most of the people graduating from that really idealistic high school went into international relations and the UN. People became consultants. A lot of people went to banking. That idealism in school doesn’t translate. If anything, it even prepares you for the fucked up world economy, capitalistic thing, though I’m not sure how.

AT: Right, that’s the cliche of that generation. The hippies grew up into bankers or whatever. I mean, that’s kind of the joke. But it’s pretty interesting to try to untangle that relationship because the result for our generation seems to be a pretty profound cynicism—to have witnessed that you could have such idealism so easily distorted and lost.

AV: For me that idealism continued with switching into dance somehow, like that was very viscerally clear. I realized for my peers who continued on an international relations path, there’s some taming down of that initial embarrassing and naïve impulse. Whereas going into performance kind of rekindled and reawakened that naïvete for me. When talking to my high school friends, they often are like, “Oh, my god, you’re so different. How do you make such a detour?” [laughter]

AT: They never expected you to become an experimental choreographer?!

AV: Being a dancer was the thing that made sense with the inner fire when I was 18. Not that I switched into dance and was like, “Okay, I’m gonna combine my revolutionary ambition with dance.” There’s no such thing. In retrospect, it felt like that energy was sublimated into dance, in ways where continuing with politics didn’t feel right or urgent or nurturing of that energy. That’s why I never think of myself as making political work. I don’t identify with that. If anything, I refuse politics because of the desire to hold on to that naïve political ambition, which for me exceeds politics.

AT: That’s a very beautiful phrasing, actually. To refuse politics, so as to hold on to the naïve political ambition that exceeds politics.

Alex Tatarsky: When you brought the word revolutionary into the conversation, what comes up for me is early Soviet avant garde art. This moment, like 1911-12 leading up to the revolution in 1917, which has been historicized as a proper Revolution. These poets and artists were really devoted to breaking apart the word, treating the word as something as powerful as a stone that can be thrown at windows and break them. However, after the revolution they’re all arrested, killed, starve to death, sent away, commit suicide. It’s all well and good until the revolution happens. Then everybody who helped foment that revolutionary fervor is and needs to become obsolete. The state can’t tolerate that kind of world breaking.

Anh Vo: That’s funny that you think of revolution through art. When I think of revolution I’m like military struggle. It’s such a central identity to me, to people who grew up in the Vietnamese nation state. We are very much defined by being able to overthrow the French and the US successively, the two most powerful empires in the world.

For me, it’s so hard to reconcile art and mass-scale revolutionary change. On a visceral level, I’m all about the militaristic overthrowing of institutions and empires. But of course, in performance studies, I’m aware of the body holding possibilities for micro-revolutions, the theater facilitating revolution, and the feminist revolutionising of the domestic spaces. I am all here for that, of course, of course, of course [laughter].

AT: There is this skepticism in your tone that is intriguing to me. Precisely because this conversation began in a place of shared embarrassment over a certain naïvete that, in order to be saved, preserved, celebrated, had to express itself covertly in other channels. So it’s interesting to hear a certain tone that distances you from the thing you’re saying… of course, of course. I know the revolution happens in the body, in these micro-ways, in the domestic sphere, of course.

But I totally relate. Because the tone of revolutionary conviction in its sort of militaristic boldness is so at odds with these micro-revolutions that might happen at a totally different, not smaller scale, but different scale. That it almost feels incongruous to even use that tone.

AV: I am curious where does the revolution live, especially in relation to your work? For me, not that I try to make work about revolution, but that history comes up all the time. That incongruity you talk about is something that really drives me. Performing all of this doesn’t cause a revolution “proper” and yet I feel so enriched by all this history of armed struggles.

AT: That makes me think of the word revolting, to revolt in all the ways, to relish being revolting. In performance I try to be as revolting as I can! To practice revolting. Both revolt and revolution come from the root word revolve, so they involve a turning, perhaps a choreography of turning towards or turning away. It makes me think of your decision to not share BABYLIFT for an audience, and this refusal as a pandemic-prompted statement of sorts. I’m thinking about how the gaze operates in relation to that material in the context of what you’re saying. How would you describe the feeling that accompanies your decision to not invite the gaze into the room?

AV: I don’t invite it but it’s there. For me, studying porn makes it very clear that even if you’re in your bedroom, the gaze doesn’t disappear… It’s still very unconscious to me. I don’t feel much different. I get to focus on the ghosts, because that piece very much dedicates itself to that history of war and tries to conjure the ghosts of it. The decision not to have an audience actually affects my larger practice than the piece tself—the piece has been a finished product.

AT: Yeah, I’m thinking about how the work that I most recently made, also adjusting for the current circumstances we’re in, almost revealed the opposite thing to me. I have been working on a piece for many years that was cancelled due to the pandemic, and I wanted to give myself the gift of continuing to explore its fragments. So for the month of September, I inhabited an empty storefront in a very commercial zone in Philadelphia and just surrounded myself with the detritus of the show that didn’t happen. I was just in there, essentially all day and night, continuing to rehearse the thing that couldn’t happen. And I really wanted to give myself the space to be non-product-oriented, like thank God, the thing that can come out of this moment is that I can not make a product. I will just be indulgent with my process, but I will put this process on display. I can fulfill my contract with the presenting institution, but it will be pure process that anyone can consume at any time of day or night. In this fishbowl storefront, I myself am the product on display. But what is available for consumption is just this unfinished mess.

However, I was so hyper-aware of the audience that it became about communicating and responding to them rather than being in my process for them to watch, or rather, being watched became the process. And what ended up happening was, there were two simultaneous shows going on: there was the show I was doing inside and there was the show they were doing outside. So they were watching me through the window, and I was watching them through the window. I could also watch the audience watch itself in a way that I had never been able to see before in the theater. So I’m still trying to make sense of this, but many people who came said that they also were never able to watch the audience in that way—to watch the passerby of the street performing for each other, and for me.

Photo By Lorelei Ramirez

ID: Seen through a glass window, Alex appears as a sad clown with a half-eaten bagel and a bottle of San Pellegrino sparkling water in her hands. Objects are messily spread across the floor and small notes are posted on the window with blue painter’s tape.

AV: It was like three weeks, right? I saw Instagram stories about it all the time. I would tell people, oh my god, this thing Alex is doing is the best thing that came out of the pandemic….

AT: Pull quote!

AV: I have not watched it and I really don’t know what happened… I really don’t. But there was something that was so compelling. I was so fed, and yet I have no idea what you did.

AT: That’s really amazing to hear.

AV: There was something about it being such a generous gesture: on display in this Nothing Office, like 9 to 5 for three weeks.

AT: 9 to 9! The thing is, if people were still watching at 9, I couldn’t stop because I wanted to give everyone the experience that the process is ceaseless. So, I would even put all of the objects in the space to sleep and tuck everything in and turn off lights slowly; I would make a moon come up in the sky and set and try to induce that there is some sense of closure for the viewer. But often, we would be in this twilight experience for hours, especially if it was one person still watching late into the night. I have very specific memories of this communication with certain individuals where we were just existing in this zone, and it felt like it could never end.

AV: You had the assumption that you were gonna be in process and people just watched, whereas with me and BABYLIFT, there’s the opposite thing of having no audience. Then we both arrive at this in-between space, this exchange between people. A lot that is happening to me as well actually, in different ways. It seems like there’s this real desire for the social that jumps out during the pandemic. But not really, I don’t think so. I feel like that social space is so present in your work regardless.

AT: Well, there’s this image that stays with me the most, that kind of breaks my heart again and again. Because I want everyone to see the show that I saw while performing my own show, but it’s impossible beyond storytelling. One evening I was creating an environment that seemed both like rain and tears with many different materials. I looked at one passerby on the street. As I was raining and weeping, this person came up to the glass and began drooling his blue Slurpee! He was expressing to me that he got it, that he was also making a substance that was like rain and tears. I completely understood what he was communicating to me. The thing that was so amazing about the storefront—because I use text so much—is that people couldn’t hear me and I couldn’t hear them. So there was no possibility to communicate with words. Here, everything became metaphor or image-based and—

AV: Kinetic.

AT: Yeah. He was communicating with this same idiom—

AV: Drooling with his blue Slurpee.

AT: Yeah. Like weeping, raining with the Slurpee, using the material, the prop that he had to join in the scene, basically. It was so amazing. And I think about this all the time: during the pandemic, the theater was closed, but I got to watch the best show. And it hurts me in my heart that no one else got to see that scene.

AV: I feel it, I’m seeing it.

Photo by Lorelei Ramirez

Alex Tatarsky: I even offered that the gaze would somehow be absent in the circumstance that you’ve created for yourself with BABYLIFT, but of course the gaze is in the room.

Anh Vo : That’s why I really stumbled when you asked that question, I was like what? The gaze? Like I still work with Vietnamese rituals and have to tell myself, please don’t research it, don’t Google it. I don’t want to learn what the proper rituals are only to bare for these USAmerican people. So I work off memory and try to do the best I can; I’m sure I butcher the rituals, and that’s fine. That thinking is still there even if no one’s seeing it.

Having no audience definitely affects certain textures of my practice. I really yearn for this interpersonal space, yearn to have people be there with me, performing with me even if I’m performing for them. All of that is very much in the gesture of not having people there. Now, I’m really, really explicit about trying to engage people. So like let’s do one-on-one studio visits, let’s talk about it with everyone I encounter, let’s do a durational six-hour opening ritual and have people come offer something. You know, this real yearning for that blue Slurpee moment!

AT: Yeah, it makes me think that the piece moves into the realm of oral rather than written history and document because it’s about imagining what’s happening. It’s about telling someone and distorting, mutating, shaping the thing as one person tells another.

AV: Like the myth of it.

AT: Which is its own kind of sculptural project, how this is shaped. Because it’s hard to write about both of these projects, even though they’re very different, like, someone cannot come and watch the piece in either of these situations, so it cannot be described in its entirety, it has to be commemorated or shared differently… It has to be grasped at in, like, glimpses.

AV: But that’s performance anyway, that’s the thing. People have the fantasy that they can sit and watch a piece.

AT: Right, they have the fantasy!

AV: The preparing, the lingering after the show, the grabbing drinks, all of that is performance, and not just the piece itself. The rumors that spread, the drama, someone gets cancelled, the gossip…

AT: Getting cancelled, the greatest show of our time!

AV: That’s why I refuse to put on a socially distant show. The theater [Target Margin] pushed me for it, which perpetuates this fantasy of consumption. People come, do the contact tracing thing, sit in a seat, watch the show so they consume a piece and they leave. No lingering. No one can talk and grab drinks. People watch the show and leave.

AT: Right. So much of live performance is the possibility of contamination, specifically. The possibility of swapping spit with someone. It’s the charge—you could meet someone in the bathroom line, you could get too close.

AV: Kind of, hopefully. In the best way, yes. Though this bourgeois structure of the theater doesn’t facilitate that really. The spectators sit in the dark and watch and then they leave. That’s why I return to the word “ritual” even though I don’t want to use it. It reflects this yearning for contamination, for mess, for negotiation. In rituals, you don’t sit and watch in the dark. You always participate even if you’re not the one facilitating rituals. And like the contamination, the exchange of spit happens in a more readily way in the ritual structure than the theater. Of course you can fuck with it, but the structure is there. So not having an audience feels like loosening that structure, that allows me to return to this ritual moment.

AT: Which makes me think of the slippage between religious ritual, artistic ritual, and political ritual. There is less distinction between these forms and functions than might be assumed. I’m thinking back to the beginning of the conversation about political performance and artistic performance as if it’s a choice between two very distinct pathways. They are not so different after all, but I’m interested in the fantasy of their difference. Which, in fact, you are refusing by not allowing the audience to validate the fantasy of their difference. Does that make sense?

AV: Yes. They are not so different but people think they are and consume as if they are.

AT: Consume as if they are!

AV: I always return to history because history materializes, and the material history of the theater is very different. The word ritual arrives through anthropology—not just anthropology as a discipline, but the instinct of “civilized” people go into primitive cultures and study primitive rituals. Like that kind of fetish. So ritual is always something inherently backward in time; that word has that connotation to it because of that history. I’m not an expert on the history of rituals, but that’s my association. When I think of ritual, I don’t think of political ritual, I don’t think of artistic ritual, I don’t think of brushing my teeth. I think of going to pagodas in Vietnam because that’s a backward-in-time kind of practice. In the sense that an anthropologist could go and take notes and then write something about it.

AT: I was laughing because I was remembering my little brother and I insisting to my grandma when we had a half-day at school, “You have to make us Annie’s mac and cheese from a box.” And she goes, “Why? I’m not making any macaroni and cheese from a box.” I’m like, “No, our mom always makes us macaroni and cheese from a box on half-days because it’s a ritual. You have to do it. It’s a ritual. It’s our ritual.” And my grandma, being from an Orthodox Jewish family in Transylvania goes, “That is not a ritual! That’s your mom not having time or care to make you a proper dinner.”

AV: That’s real. [laughter]

AT: That’s really real. [laughter]

AV: That’s not a ritual. It is, but it is not.

AT: It’s not. Or, I don’t know… There’s something that feels both tender and sad in the way that we do, but do not, have ritual in that way. The ritual of the boxed mac and cheese…

Anh Vo: I do think my work provides a chance for me to say fuck you to the rich, white bourgeoisie. Sometimes they might not even know that I’m saying fuck you to them just because of the Asian subtlety thing.

Alex Tatarsky: Wait, I should lend you this shirt. A classic Canal Street t-shirt that says Fuck you, you fucking fuck. I just wear this t-shirt and it does the work for me. [laughter]

I do wonder if that has to do with the bodies that we each inhabit on stage and the different but entangled histories they carry. Because I certainly feel like it’s irresponsible of me in my particular body to say, fuck you, without also saying, in some sense, we’re the same. Like, to say fuck you, I also have to be saying fuck me too. Or maybe the strategy that I’m interested in as a performer is saying “fuck me” as a way of being able to say “fuck you!” and have it be heard and absorbed.

AV: I get that. What you say gets to this abject theory that there’s no real division between you and me. And yet whenever I perform, especially when I perform works around the war and communism, the gaze of otherness is so real. I can’t identify with the audience through the work somehow. Even though the audience is very heterogeneous.

Whenever I show the war stuff like BABYLIFT, I feel a delineation between me and you: I’m bringing my history to you. Through my history, I implicate you so that you find yourself within my history. It’s a very clear thing; maybe it’s just energetic. But it also feels very fetishistic. Like people engage these materials with some sort of curiosity in ways where they don’t just sit and watch, but they sit and gaze.

Photo by Maria Baranova

ID: Anh solemnly kneels in front of an altar wearing only a dance belt. Projected in the back is the iconic photograph of Thich Quang Duc’s self immolation (1963) during the Vietnam War.

AT: And you feel that as a performer?

AV: For sure.

AT: How do you keep making the work? That sounds really intense to experience as it’s happening, within the duration of the performance.

AV: It feeds the work, I think. Like gazing through the lens of whiteness into my own

History, though it’s not a possessive thing. In college, I learned about the war, Buddhist philosophy, and Confucian principles through mostly white men. There’s that anthropological ethnographic gaze that somehow allows me to access my culture. So playing with that in the performance enriches me too. It’s not just a violent thing. And I can’t articulate it, but it is an intense energetic experience. Similar to you, I do perform as a politician a lot. As a revolutionary charismatic figure that is really in control of the space, of the energy. So that fetishistic thing gets a little bit more loose.

I’ve seen a few of your works where they also reference political stuff, history, contemporary events, but there’s this sense of a shared history that can be assumed somehow. Whenever I bring history in, I always have a kind of didactic question: Oh, shit, do we have to teach people this thing?

AT: Certainly I’m writing and improvising from the specificity of a particular discourse and a set of associations and cultural moods, fictions, fantasies, nostalgias. That comes from some kind of a shared aesthetic, like saturation, like assuming that a lot of the audience has been saturated in some of the same mass imagery and sounds and words.

AV: Yes and you turn it inside out.

AT: I’m very much thinking about codes and secrets and ways of playing games, so that you’re able to say something that you could get killed for. And how you can keep the game going so that anybody watching can think that you’re just playing, can feel even invited to play along, and then you’re able to communicate something that is a threat to that same game. I guess I’m thinking of performance as a game of dreidel, a kind of spinning top Jews would use to cover up and therefore enable the study of dangerous texts. This is coming very much from mystical Jewish philosophy of language where there’s this base of understanding, and then there are all these secrets that take a lot more knowledge to access.

AV: Probably not just knowledge. Sometimes being there, immersed in it can be translated to knowledge. Even the word knowledge feels so rational.

Alex Tatarsky: I am also reflecting on how surprising it is to realize that you’ve ended up in a particular life. And to me, it feels very economic. Like, entering into adult life during the recession of 2008 made me feel like a certain kind of economic stability was not possible.

Because of that precarity, there was strangely an opening for making stuff, making art. Which is, in some sense, connected to what you’re saying. The sense of having watched the whole system that may have held some hope for us as children clearly not function.

Anh Vo: So are you saying that the recession solidified or prompted you to dive into this precarity to performance? Do you bookmark your presidential ambition to the recession?

AT: I suppose in a way because the Obama years were filled with such hope, and also opened up a wellspring of despair. Because even if there was a certain kind of representation in the White House, you could still see such violence and such horror.

AV: I really don’t even associate that with Obama. There was a moment I realized politics is just evil and to engage in politics you have to engage in evil practices. And unconsciously,there’s a point I was willing to do that. To be a politician you have to be very manipulative and I was preparing myself for that trajectory. And then at one point, I was just like, “no, I am not willing to engage in that practice” and then it spiraled out into this performance thing.

AT: Although now that you mention evil…! It’s a curious word. Because performance is also one place that complicates good and evil, good and bad. In a way, performance allows for exploration of evil as opposed to denial of evil. Maybe the politician has to deny involvement with evil, whereas I would hope that a performance can crack that open, in different ways and to different degrees. Like, dance with evil essentially.

Photo by Walter Wlodarczyk

ID: With eyes wide open and a big smile on her face, Alex sits in a deep squat spreading her legs apart. This position exposes her white underwear, loosely covered by red fishnet stockings and further accentuated by a pair of red high heels. Red, white, and blue metallic fringe sits in a tangle atop her head.

AV: Do you feel like you dance with evil?

AT: Yes, of course.

AV: I don’t but I’m glad you do. [laughter]

AT: Wow, that’s amazing. [laughter] Can you say more about that?

AV: On some level, I truly believe performance,or at least my performances, don’t affect shit. It does, but it don’t. There’s this existential acknowledgement that the stake is low. Politicians, you kind of have to play with people’s lives. We don’t… We do, but not really. So even if you dance evil, evil feels just so small compared to the stock market, real estate, or banking.

AT: Yeah. At the risk of alienating all my funders… I’m aware of where all real money comes from. And being okay as a working artist is engaging with my reliance on practices of evil to the extent that the word evil itself ceases to be all that helpful. But it’s very much on my mind in trying to make a living. As they say in show biz, you can’t make a living, you can only make a killing…

AV: Wait what do you mean make a killing?

AT: It’s an idiom for making a ton of money. So you can’t make a living, you can only make a killing.

AV: [gasps] Oh…

Cover image description:

In a white onesie with red flower petals in outstretched hands, Alex seems to be crying in the middle of a pile of stuff. A small clown figurine is collapsed in a spiral to her side. Vinyl letters on the storefront window obscure parts of her body as well as the performance space. The letters spell the word “WHY.”