Download this interview as PDF

Guy Yarden: I listened to the podcast that you have online about Blind Date…

Bill T. Jones: …which is a bit outdated now, but…

GY: …and I thought what we could do was to provide a link to that and jump off from it, especially since you are saying that it’s older than where you’re head is now with…

BTJ: That was actually done last August before the piece premiered in September, and now the piece has been premiered, it’s toured, it’s been worked on, and even we made changes yesterday, sections have been cut…

GY: I was curious if you could talk a little bit about the driving elements that went into the making of the piece and what the genesis of the piece was, what prompted you to go into that area. To some degree I don’t feel like it’s new territory for you, but…

BTJ: Well, you know, every piece seems new to me, because I keep changing. You might have found this with other artists, when you ask that question, the kind of instant archeology that goes on trying to get back to the first impulse. And, I always say that, usually, one piece comes out of another.

But, what happened? I do know that we were in Dortmund, Germany — six years ago? And they were opening one of their new musikhalles and everybody; the governor of the province was there, a very important audience. It was a gala evening around Beethoven. Why we were there? Well… I did one solo to Beethoven, we also were dancing a Shostakovich piece, and a friend of mine who used to work in Salzburg was now the director of that, that’s why we were invited. At one point, (this is the most amazing thing) the nightmare of galas, a man who looked like he was central casting for a German professor, came out, hair flying, shuffled on with sheaf of notes and then, in German, (and everyone showed him great deference) he began to speak. And he spoke for half an hour to forty-five minutes in the middle of a three-hour gala. And he was lecturing them about German language. And he was getting laughs and so on. Now, I found out later that everybody of a certain generation remembered him because he was on either every Saturday night or every Sunday night, his name is Peter Wapnewski and he is a philologist and a Wagnerian scholar, and all things German. So, his job was, I think coming right after the Second World War, to come on and teach German people about their culture. And, that night, I wouldn’t say he was castigating, but he was decrying the way the language had been weakened. Unlike the French, which he thinks are overboard, the Germans don’t police their language, words come in. And he was particularly harping—not harping—but he was saying things like honor, valor and courage, words that used to be very, very important in the lexicon of German thought, and he was wondering if those words were bankrupt.

I have a translation of it somewhere if you’d like to see it, but this was Bjorn whispering to me translating on the spot. He said some provocative things. For instance, if we assume that individuality and equality are two goals of our contemporary society, he thinks that individuality and equality are opposites, they are nearly incompatible—were you have the maximum individuality, you don’t have equality, and where you have the most equality, you don’t have individuality. The whole idea of democracy is thrown off, at least the way I took it, so obviously I was primed to hear it a certain way. And this idea of honor and valor, and courage — the election and that nasty debate that was going on where that term—patriotism—was being used as a kind of litmus test – a light to shine on somebody, even a proven war hero like John Kerry, suddenly he gets swift boated — his integrity is besmirched, simply by hearsay and what have you. And then there’s this media machine—and this language, this mendacity, is made, sort of, a religious cant. And I was mesmerized, like so many, by the debates—what was being said, who won, and so on. ‘You’re a patriot, you’re a traitor, you’re a patriot, you’re a traitor.’ Like everybody else, I began to really think—this is we, those who (and I dare think of myself as a member of a community and that’s a big one for a modernist artist) we, the progressive forces, we need to make a change. We are going to win. I was in Arizona, in Tempe, a pretty progressive community. People were on the street the night before giving each other thumbs up, horns; the next day – boom! – we lost. It was… Well, I don’t know how you felt, but for me, it was something similar to 9/11. I don’t know if it’s overstating it, but—this is where we’re at. ‘This is what happened to you, foolish, foolish, ‘60s person that you are. You really thought that the project of progressive politics was unchallengeable. You fool, you liberal fools. And you see what has happened. You assumed that you had certain rights, you assumed that everyone thought the same way about freedom of speech, about determining your life no matter what you’re sexual orientation. You assumed all these things, look at what these last election was about: moral values, patriotism.’ And that’s when I thought, okay, the dance company. I love it, God knows. The child that Arnie Zane and I had, which in its own way is a political statement, long before there was the issue of gay marriage, we had the notion that we had a union that was sacred and a profound union that expressed a way of healing all of our existential wounds. That’s what we thought that marriage was.

GY: The marriage as reflected in the company?

BTJ: In the company. So, I looked at this company now and I said, ‘there’s all that is going on in the world, and are you still in that art-world ghetto?’ And we never wanted to be and it’s no accident we’re here (northwest of NYC). When we moved down from Binghamton, we had the option of taking that $800 a month that we had and putting it into a little place over in Alphabet City, or we could invest in a piece of property with land and trees. He grew up ten miles from here, Arnie did. And we chose this life. It was a very important decision. We did not want to be in groovyville, you know. We did not want to be in any ghetto. We did not want to be in the gay ghetto, we certainly did not want to be in an art ghetto.

And I thought, when I looked at my dance company (I guess I’m one of the survivors from my generation of choreographers, I’ve done well, it’s kind of a joke when you think about how hard it is to do it, but I’m considered a success),’ what is this project about, this dance company? So, let’s test it on this issue that you’re feeling Bill, about the relationship of what you do in the studio and the stage to the larger political discourse.’ And maybe that’s what you mean, this is not new territory for me, but I actually thought…

GY: I mean in the broad sense.

BTY: I understand. I say, why don’t you let the dancers weigh in on this.’ I know that some of them are only twenty years old, and they look at me like—‘are you serious? You think I even care about the elections?’ And we had fights about it. Because I was saying, ‘well what do you think about this issue, and that issue that they’re talking about. What do you think about them making decisions in your name?’ I turned to one of the gay people in the company, a man, and I said, ‘what do you feel that people are really debating your right to be able to marry.’ And he sort of looked confused and said, ‘I don’t intend to get married.’ What about… it isn’t about you, it’s like when a friend of mine said years ago, we were arguing about racism, he said ‘what are you talking about, you’re wearing a coat and a tie you know, why are you talking about racism.’ In other words, ‘you got yours, why would you identify with another group, don’t be a hypocrite; it’s all about you, isn’t it?’ Well, I thought that we… why did I have this notion, that with progressive art making came progressive consciousness about a societal community. I know that a lot of people who are artists are deeply alienated human beings. I am one of them. As a matter of fact, I say I was bred to be alienated as who I am in this country—a black man, what have you, maybe gay, but I think that most black people would say, at least from my generation, this country quite frankly doesn’t want you.

GY: When you say bred, you mean bred by the country, not by your family.

BTY: The culture, the entire culture bred me to be racist, paranoid and degraded.

GY: —but not cynical.

BTY: I refuse to be cynical. That is an act of will, not to be cynical. But when I was talking to my dancers I realized, this is what your generation (I’m old enough to be the parent of a lot of people I dance with now)… The ideas that we had about absolute freedom, the ideas that we had about our obligation to anything bigger than ourselves, has bred a generation of people who are disconnected. Now, to be sure, there is a lot of activism I see in young people. And around that media-driven debate, I think people have to take sides. But I want the dancers to find a way to bring that discourse—which you don’t think it, but you’re living it everyday—into the studio.

GY: Do the dancers who work with you—do you have a sense that they understand what they do as a political act? Just simply that they are artists.

BTY: A generation ago, that formulation would have been quite clear. I don’t think right now, the way the discourse is, people even think in those terms.

GY: Do you have any idea why they don’t?

BTY: Well, mea culpa, mea culpa. I think it’s because the generation of their parents, my generation, put maybe personal freedom and individuality and cynicism, I think, before everything. They thought that all the battles had been fought in the 1960s: blacks, women, gays. ‘It’s already been fought, there’re no issues. And we’re all groovy, I don’t have any problem with you being a …,’ or, ‘I have a lot of gay friends, you know. We’re all groovy…’

GY: We see a lot of these issues in advertising now.

BTY: Right, right. So, it’s over. And that next generation actually believes, well, that’s the voice of my parents or grandparents, they’re uptight. In our generation, we don’t have these problems, so what’s the big deal now? What do you mean ‘political’? What’s politics? I think that is, roughly, the way a lot of the young artists, that I come in contact with, behave. Now, if I were in the Bay area, would I feel differently? In New York, I’m not so sure. Now, I think there’s some (do I dare say) respectability, cache in having a healthy dose of political anger in the art world. But certainly when Arnie and I came into the scene in the late 1970s, at the height of minimalism, I don’t think people were thinking in those terms. So, in a way, your question is about language—how people use language. Someone asked me the other day, in Germany, is it possible to be too political? They want to talk to me and they’re assuming…

I mean, they’re talking to an artist who is incredibly self-involved, you know, I still believe in striving for transcendence through form. No, I’m not out on the street with a petition right now, I’m actually trying to find a way to make poetry that speaks about the world I live in. I said that it maybe it goes back to Ken Kesey and the Electric Kool-aid Acid Test. Remember? You read it, right? As you know, there was this bust, The Merry Pranksters, and they were all tripping all the time, and they had speakers, so what was outside was being blasted inside, and what was inside was being blasted outside, and they had this thing that, when you had an issue, you would go up to the front of the bus and you would speak the issue. That’s how the term up front came about, as I understand it—being up front. Being political was being up front all the time. That’s how I understood what politics was, interpersonal politics and societal politics. That’s a crude way of looking at it, considering what I know about politics now, but I think it’s maybe a good rule of thumb. You want to know what politics really feels like? At a dinner party, stop the dinner party when someone says something that you disagree with. You know, be a bore. Make debate and discourse when you want to.

GY: I was going to get into this later, but I was reading in your blog, the reference to when you were in South Carolina and that event that happened on stage with the person booing and your reaction and I was thinking back to other times when [I heard] that word belligerent. You’ve used it about yourself, more than I’ve heard other people refer to you that way, although I assume that at various times, people have. And, I know what that is like to be considered belligerent. But I wonder about it, because (earlier) we were trying to really identify what the core issue is, and I was using the term honesty and that a level of honesty is not welcome, in a sense. But I think that the term you just said, was a little better…

BTY: Being up front, which is an old counter-culture term. And I don’t know if he said political or if I made that connection later, that being political is being up front all the time. First of all, I don’t think you can really do it. This is a middle-aged person speaking. I don’t know if I can really practice that with the same rigor as I used to. I can’t quite afford to practice it.

GY: Why at the dinner party is it considered to be a bore?

BTY: You know what the rule is (I don’t know where this rule comes from), there’s three things you don’t talk about over dinner: politics, religion and it’s either sex or money; I think it’s probably money. It’s just bad form to speak about that at dinner. Where did that come from? That’s generations back, when people had genteel meetings. I don’t know, is that from the salons in the late 19th century? Is that a more bourgeois notion? When you get people together, if you want an elegant evening, you don’t want to bring up anything that is going to make people either too passionate or divided—or, stop the conviviality, the flow. We’re here to enjoy each other, enjoy the food.

GY: So, the 18th century Enlightenment that you refer to, and those philosophers, were they doing something else.

BTY: They were revolutionaries, what can I tell you!

GY: Were they doing that at dinner parties?

BTY: They probably were. In their class, I wonder… They had such a sense of mission. They were making something they knew was unprecedented. They were so excited about, I bet they… But then again, they were always with people of their own class, their own race, with very strict hierarchies. The women after dinner would leave the room, except, they tell me, Abigail Adams, John Adams’ wife. She was his most important confidant. He had the utmost respect for her intellect. So, I don’t know. Were they doing that?

Now, pulling me back into how does an artist behave now at this metaphorical dinner? How does an artist who is mid-career (an artist who is on the brink now of, perhaps, being awarded a few million dollars to build a home and a research center, on the cultural corridor of Harlem), how can he afford to comport himself? People would often ask me in interviews, what should an artist do Mr. Jones, since you are, as the French would say, an artiste engagé—you’re engaged. They used to say, you are militante, and I would say no. Militant to me meant the Black Panthers and such things. But no, militante means what the feminist would have said in the ‘70s—assertive. In other words, the French have this notion of being engaged in the world. I guess other artists are disengaged?

For me that was a great project of modernism, this fragmentation of the world and disengagement from the world. So, when they would ask me that, ‘what should an artist do?,’ Assuming that I was saying that all artist should be pounding the tables and taking positions, I said, ‘first of all, you need to realize an artist does not have to do a goddamn thing.’ The artist should be the freeist person in the society, running sometimes literally naked though the streets, thumbing their nose all dogma and received wisdom, even when it is politically correct. That is the project of an artist. Maybe it’s a bit of a romantic notion of an artist as madman and madwoman, but I think that’s a healthy one to keep your eye on. Of course, there’s an addendum, an artist is a man or a woman or a person of indeterminate gender with a location in the society. What class do they come from? So, they have a sexual orientation, a gender, a class, a place in the world that, as we well know, affects how we relate to the world. Now, what does that person, that the artist is, need to do—need to do? That’s what we get down to. Can’t tell you what you should do. What do you need to do? What do you need to say? That’s how I answer that question about what is politics in its relationship to art.

GY: Going forward with that, (and I’m going to be imposing some of my own opinions in asking this question) the development of an industry around contemporary dance over let’s say the past 20 or 30 years, I think we can now effectively call it an industry, my sense is that the development of the industry, while it enables much in terms of creation and presentation and exposure of artists, etc.—it also diminishes the possibility of embracing the artists who would run through the streets naked, yelling their mind.

BTY: You know what? That’s a hard one, isn’t it? And more timely than… I’ll try to deal with it later, but, you know, has it ever been different? Someone said to me years ago—how much freedom can we have? And, I said, we’re going to have as much freedom as we’re willing to pay for. You can starve in a garret, on your terms. In other words, you can take the high road. Nobody is telling you that you have to have a comfortable life. No one’s guaranteed you, so run naked, burn your bridges. Who among us, of the survivors, have truly been able to live by that? I say, whenever I get on my high horse in front of a group of young artists and talking about their future and their relationship to society at large, I say, ‘this is the deal, right here you can choose to be a wild man or a wild woman, and you can live it on your terms.’ People have done it. And quite frankly I have a personal pantheon of those persons. What are you? What are you made of? What do you want? Do you want a middle class life? You feel one way at age 20, you feel another way at age 55, you feel another way at age 70. So, be careful about taking positions that are too firm. But don’t worry so much about the future. You’ve chosen what I can only consider a transcendental path in this world, and that is always perilous, often lonely. So, go for it. You wanna run naked? Go do it, but realize that nothing is free. You gotta pay for everything. Can you pay?

GY: So, you said be careful about being too firm, which bring me back into the piece, ‘cause you talked somewhere about…

BY: …about toxic certainty?

GY: …about toxic certainty and a notion of values. I felt, in here, you were referring to the 18th century Enlightenment philosophers as an impetus for the piece.

BTY: Well, just going back to a tradition that we once could all agree on. So, let’s get rid of the schism between left and right and progressives and all. These are the things that the founders believed in. Where are we around those ideas now? Tolerance, progress… deism? They were all believers, but their deism also taught that everyone should be allow to have their own expression of deism and they also believed enough in science and progress that they should be separated.

GY: But there was a lot of division amongst them, I mean, there was Jefferson and then there were others.

BTY: It’s true, but which ones prevail; what do they teach us in school? The separation of state and church. I realize that we not all heard it the same way, if you listen to Antonin Scalia and people like that speak… but where were we going with this?

GY: I was speculating on this notion of values and this increased level of certainly that people are exhibiting. I’ve noticed it a lot too, even in this President’s term. It has, sort of, created this level of mindlessness of thinking and it’s almost like people are losing their ability for self-reflection. That’s when I finally understood the title of the piece, it was at that point…

BTY: You mean…

GY: It was the ducks. The sitting duck and imagining the army recruiter and the young guy waiting to be recruited and the blind leading the blind and that’s the blind date.

BTY: Believe me, the title is purposely ambiguous in that way, so we have to find the way of what does this have to do with that? And there’s a reality show looming there. For a person who has used, at times the stuff that comes hot from the heart and psyche and work, I’m really repulsed by the notion of reality shows. This notion that we’re looking at the truth in life and it’s for entertainment. There was a show called Blind Date, and they have a set up where they would arrange for people to meet and then the cameras would be running to see how it would go. So, I should say I chose a trash title for a non-trash topic. You are right about the blind leading the blind, but it’s even more about our present discourse, and we don’t know… Now, is it, ‘Bill, you don’t know?’ Because there are those who would say, I know where it’s going, I’m sure Noam Chomsky would say, ‘I know where it’s going, history has taught me.’ And there are those like Fred Dobson who would say ‘I know where we’re going if we don’t change our habits.’ I don’t’ know where we’re going. And I speak for myself and I feel I represent a lot of what I call progressive people who I think are experiencing, what I called a few years ago, spiritual fatigue.

You know how in The Virgin Spring by Ingmar Bergman, after the father (this good man who believes in Christ and all), his daughter has been raped and killed in the forest and he has an opportunity to wreak havoc on the people who did it, and he does it right down to killing a child, and he’s out on the forest over the place where his daughter is and he turns and says: ‘Oh my God, I don’t know,’ with this gesture like this [opens arms to the sides]. Big question for Bergman and that generation. But, I don’t have the deity to turn to and say ‘Oh my God,’ all I have is, ‘I don’t know.’ I don’t know what right action is. I don’t know what my relationship is to the carnage that’s everywhere. I don’t know why there has not been a suicide bomber on 42nd St. yet. I’m glad, but I don’t know the relationship between that fact and the fact that there being people tortured right now on my behalf, so that I can be saved to go to my modern dance every day. I don’t know what I’m supposed to do.

GY: In the talk to Tides Foundation, you listed three areas that you’re continuing to work on in Blind Date: to articulate the potential in human movement; to discover, assign and expand the meaning of such movement; and to strive towards the beautiful. I wonder if you would be interested in talking about the assigning of meaning to movement. Is that always important to you? Is it this particular piece? And do you land anywhere in particular on that whole of issue of meaning in relation to movement and dance construction?

BTY: Well, I heard Merce Cunningham very clearly when he said any movement can follow any other movement. We are also students of Yvonne Rainer who was a great champion of pedestrian and found movement. Steve Paxton, that generation, they were great because they freed us to think about movement not necessarily coming from a predetermined, codified set of choices, as in most techniques—Graham Technique, what have you—these movements are set, this is what we do.

We could look everywhere for movement and the value of choreography was determined by the depth of formal understanding, invention, and sensibility of its creator. Boom! That’s what movement is, vocabulary—and a problem actually for those of us, now, who feel a desire for style, by the way. But, there’s the movement.

Now, I’ve always felt the desire to talk about something or to express something—feelings. The model that I have, I think, comes from story telling in the African-American tradition—my parents. ‘I’ll now testify.’ I stand up in front of a community and I testify. And then the community responds back and we have this communion. But they know, they can, ‘I hear you brother, I feel you.’ Now, modernism — ‘I see what you’re doing.’ Do I hear you? I feel you? ‘I see what you’re doing.’ I don’t know which language is really mine. I get a great joy out of looking at purely, if I can use that term, purely formalist work. Arnie was a great fan of Lucinda Childs. That was his favorite choreographer.

I have been trying to, and I don’t know if I was always conscious of this, to actually make an art that was a communal one, that testified and invited communion. I know these are dangerous kind of terms: a communion is a religious term, I know. I don’t know if I’ve always been successful. I used to do solos that were I would try to move abstractly and then I would try to tell very tangible stories, assuming that the eyes of the viewer will combine that, to find relationships. And I had some success with a piece called 21. I now do a version called 22. 21 shapes are performed—almost like a tone row in atonal music—that were taken from sports, film, literature and whatever, and then I would tell a story, tell two stories. Incidentally, those shapes would have to be done and named constantly, and then try to tell a narrative with those shapes continuing. And there would be strange kind of coincidences, where I would say one thing and what you were just talking about has a strange relationship to it, sometimes direct, sometimes elliptical. That’s one way that the movement and the content of a story, wrap on to each other. How to do that with a big group of people is been something that I’ve been struggling with, particularly when I insist on using text.

GY: And using their personal story.

BTY: Right. So I continue with this strategy of keeping the movement as abstract as possible and trying to ask for more and more clearly legible use of text. And the two of them coexist, sometimes easily and sometimes uneasily. And the viewer will assign meaning. I’m going into a new piece right now (Blind Date has some of that) called Chapel/Chapter, which you probably read on the website as well, and I started with, of course, movement. We always start with movement. But I’ve also started with three texts, all of them disturbing texts. One of them about the murder of the child up in Spanish Harlem, last December, whose father beat her to death because she took a yogurt out of the refrigerator. But it was a bigger story than that, she’d been tied to a chair, she’d been forced to eat cat food until she vomited… It’s strange, the New York Times, the way that they reported it. The father’s confession, this pathetic character, but it’s a kind of reasoning: ‘She was a difficult, troubled child. She tried to set her brother on fire. We had to tied her to a chair so we could sleep.’ Then there was this killer – the bound, torture, kill guy – who was wreaking havoc. This horrible murderer who came back within the last few years, started this up again, then he got caught. Now the transcripts are all there on the internet of the judge asking him, ‘so then, why did you choose this family?’ ‘Well, it was almost an accident. I was going to go next door, but their door was open so I went in and I waited for them to come in and I confronted them. Well I told old her this and I told him that and I separated them. I tried to make them comfortable. As I went back in to deal with the rest of them, well, he was struggling and I choked him and I thought he was dead. And I went back in and I started in on her…’ ‘What do you mean you started in?’ ‘Well, you know, I have these fantasies, and she was fighting me, so I strangled her. I thought she was dead, but she came back alive.’ Just the way they’re going back and forth in this most… it’s manageable on paper when you hear it. Now Daniel [Bernard Roumain], my musical director says if you listen to the website and you hear the testimony, in the background, you hear the family wailing. But the killer is saying ‘You know, I used to walk my dog, we were neighbors, I waved at her every day, nothing personal…’ Aaagh!

And then a strange report, not so strange, but chilling, the sentencing of hijacker. Did you read that report of the exchange between the judge and him, the last day? This is the most curious one and most difficult one because it’s somehow political. Everyone was wondering if the jury was in fact going to give him the death penalty. And, the jury ultimately did not give him the death penalty. He proclaimed in front of the media, of course, ‘I won.’ The judge was obviously pissed at this and the next day she said, ‘you said that you won, but you did not win. You’re not going to go free,’ and so on and so forth. And he said, ‘Well, it was my choice.’ And she said, ‘You have no choice. Everyone in this room will leave today and smell air and feel the sun on their body. We’re sending you to a place where you will never be heard from again.’ And this is the part that I love, “To quote T.S. Eliot: You wanted to die a martyr, but you will die with a whimper. You know, that term?” And she is quoting T.S. Eliot and saying to him this is the last time you will be heard from. Bjorn and his mother said that in medieval castles there was a place called oubliette, which comes from oublier, to forget. You open a hole, you throw somebody in it and you forget them. What’s more, they’re designed so they can hear everybody around them as they’re starving to death and they can shout out and nobody will hear them. Now, this prison was designed in such a way that they never come in contact with anybody except the guard, when he slips the food to them, the toilet, everything. It’s designed so that you go into extreme isolation and as the Times said ‘and they deteriorate quickly.’ So, to my mind, what I heard her [the Moussaoui judge] saying is, ‘we are going to bury you alive.’ Here it is again, this question about what do I do. How do I feel about people who do bad things? I allow all these proxies. How can I even allow myself to think about the acts that are committed and do I allow myself to even have a feeling about them as people? Does anyone deserve to be buried alive and, particularly, in my name?

Okay, I‘ve just given you my schpeel of text. Now, what does that have to do with the movement? I have been trying to find ways that the text is introduced when we see certain movement. Therefore, that movement then is, hopefully, in the gut and in the mind of the viewer, is associated (it’s not literal movement at all) with that horrible thing. Now, can that movement, almost like DNA, move through the piece and, in a way, leave a trail of association and meaning, even in its most abstract passages? That’s my project right now. Because ultimately it’s about morality and not forgetting. Now, what is there about abstraction that we love, when it’s’ free of content—is that true? Or, open enough that we can bring our own content, that’s a favorite one, isn’t it? They leave enough space that we can get in and bring our own content. Well, okay then, I think that’s who I am. Maybe that’s why I love Merce, maybe that’s why I love Trisha’s work, the non-theatrical work in particular. But is it the work that I need to be making? Knowing how my heart works and my mind works? This discomfort I have always in a way in being alive? I’m a kind of moralist or something, I don’t know what it is. Is that the work I need to be making? That’s what movement and meaning is about for me right now.

GY: Where this was leading me, in thinking about the question and seeing that you had referred to the importance of assigning meaning to movement, was…

BTY: Maybe I should correct myself. Do I want to assign meaning or do I want to reveal meaning?

GY: You want to allow for the possibility of assigning meaning, that’s what it sounds like you’re saying.

BTY: Yes, right.

GY: And, I’m often very painfully aware of this because of the work that I do, both as an artist and as an administrator, and I don’t know if I’m imposing something or not, I may be, but there is an aesthetic divide, or aesthetic divides—multiple ones—usually, I tend to think created by artists that are either opposed to each others work or are dismissive of each others work along philosophical lines. And then there’s what I call a macro level of decision makers in the form of administrators, curators, philanthropists, press, etc., who are in a sense the arbiters. Going to what you’re looking to do in Harlem, and trying to engender community, I wonder how do you create community that simultaneously can, not embrace aesthetic divide, but more that there’s room it, but that at the same time, there isn’t really divisiveness, in the sense of—we’re over here and we’re over here. Because in my mind, it’s an economically weak industry, and we make it weaker through artists not accepting what each other does and instead saying—‘that shouldn’t be funded, or that shouldn’t get gigs, because this is what’s really new and important now.’

BTY: Well, you probably know more about that than I do.

GY: But, you must feel it.

BTY: I do feel it and I’ve been wounded by this feeling. Arnie Zane and I came into a world that was never… they didn’t know how to deal with us. They didn’t know how to deal with my showmanship. They didn’t know how to deal with (in some quarters) what was seen like our overt pronouncing of our relationship. I didn’t think that, we were just being ourselves. We were ambitious. I’ve been wondering about this. I always thought that Movement Research and, to some degree DTW, maybe, they were places that were supposed to say, ‘we believe in diversity, we believe that…’ Who was it, Merce or John who said—‘there are many ways’? It used to be John’s way of thinking. You can imagine what snobs they were about the work they made, but they would they would always preface criticisms by others with ‘there are many ways.’ I thought that was what Movement Research was about and I thought that’s what a lot of the downtown spaces were about. And admirably, I use to think that it was racially…that there was a racial divide. But, I think now, there’s room for Ron Brown and Reggie Wilson and Rennie Harris. There’s room to be Black now. There’s room to… and still be cool, I think, you know. Or is that because of the funding? Is that because of the arbiters who’ve…

GY: The tokenism?

BTY: Well…

GY: Or is it less token than it used to be?

BTY: What I’m getting at is. I think, I don’t know, maybe you can tell me, I feel like a pollyanna here. I believe that there is more room for people to have political points of view, to use narrative. Could you make a dance and be taken seriously at PS122 that was built on Graham technique—well, there’s Richard Move. I think the scene has answered that question. Now, is it fashion that answered that question; is it box office that answers that question? Is everybody concerned with getting the largest demographic in there? Funders make us do that. ‘What are the underserved communities?’ That was a few years ago, the Wallace Foundation grant. They wanted to give you a grant to identify the communities that you would like to have in your seats, and then they would like to give you a grant to help you cultivate programs that would bring in these very persons. So, it makes you begin to think in a certain way. I always thought that anyway, I was interested in getting more people of our color in there, keeping the generations fluid, and so on. But, looking back at the groovy period of my imagination, Judson Church, maybe later, the Grand Union, they were people who were pretty like-minded people. They were probably, I could be wrong, I think the demographic would show that they were similar race, probably similar class and they were all in this kind of enclave of experimentation, and a bit like a balkanized notion that ‘the world is so corrupt and materialistic; they don’t understand this high minded work we’re doing in here, so fuck the world, we’re going to do it for ourselves.’ That’s maybe never been different.

GY: But then those organizations that you mentioned, in this case Movement Research and DTW, grow out of those movements, very directly. And over 20, 30, 40 years, they’re striving, it seems to me, for addressing some of these issues.

BTY: How are they doing? I believe they’ve done well, haven’t they?

GY: I think they’ve done well and they struggle with it on a daily basis continually. When you’re inside one of these organizations, there is a general agenda of what can we do to make the artists that participate in our programs a more diverse group. How can we reach out to different populations around the city, in different areas, across racial lines, ethnic lines? And it’s incredibly challenging for them to actually be successful at it.

BTY: But, aren’t you rewarded for it?

GY: You mean financially?

BTY: Yeah.

GY: Yes.

BTY: So I’m not sure if it’s a noble effort or is it a cynical effort. Maybe you can tell me. It probably is a mixture of it.

GY: I don’t know if it’s noble or cynical. I’m more wonder about its effect on the art in so far as what a mission of an organization says its artistic mission is. So if somebody is saying their artistic mission is to foster experimentalism. And then the artists that associate themselves with that organization around that mission, the organization becomes identified by the artists who associate themselves with it. That’s the way I tend to see it.

BTY: And that’s a first stage, I think. And then after a while, if you get enough root growth there, then you can maybe re-examine what you mean by experimentalism. You know, I quote—and I wish I could find the source material for this—there was a moment in the 1960s when there was a conference or something going on, and there were the young turks, like Yvonne Rainer and all, I think she was quite a big voice for that (and then there were black modern dance companies on that program or on another festival at the same time) and she made the statement— ‘how can they do revolutionary work using such traditional means?’ (paraphrase) Now, their notion, how they used the word revolutionary and all, and her language, said, no way. Now, are we still there? If I were administrator right now in either of those organizations, I’d have to know enough about the differences in the social contexts out of which artists come, to understand, for that artist, what is experimental? And the criteria that was the bible, circa 1960 to 1970, of experimentalism, I think I would be falling down the job if I had I not rethought that. And that is the challenge I put forward to all the progressive cultural workers right now, writers in particular. When you criticize a work, do you know enough about the context out of which that work has come, so that you can maybe adjust your critical criteria to understand why that person is making those decisions and—what is a risk?

This is not original, Meredith Monk did it years ago, and I know Ishmael Houston-Jones did it. When I did Uncle Tom’s Cabin and I had Stella Jones, my mother, on stage, first of all, I remember making people (a video artist I was working with at the time) uncomfortable even talking about the issue of faith. Realize, Arnie Zane had just died, that was my whole understanding of my own future, and what was worthwhile was shaken. And I went back to these sort of iconographic foundation myths in my existence about the meaning of life and faith, and so on. So when I talked with people who are acting like, ‘what’s going on, why are you using language like faith?’ But, I brought my mother on stage because I said, in a classic postmodernist tragedy, I was going to, in an unmediated fashion, recontextualize her and as a result recontextualize the performance…

GY: and you.

BTY: and me, and me, right. Yes, thank you for that. And I said, do people understand this is not some sentimental gesture? It was that, but I’m actually trying to show you what my heritage is, how I understand performance and how I understand… there it is. My mother could never give me anything material, but what she gave me was this amazing, deeply profound notion of an unambiguous life. There is God, there is Heaven, there’s Hell. And what you gotta have is the Sword of Truth that comes with Faith. That’s how you get by in this world. I asked my mother — well, slavery, uh, Christianity is a slave religion? My mother (in the early days, first version of it done at the Black Arts Festival in Los Angeles, right after Arnie died, maybe in the early 90s), I asked her that question in public and she said, ‘well son, we were over in Africa like savages, running around, and if it took slavery to bring us to the Master, it was worth it.’ Boom! That was her belief. So I said, what I wanted to do in that performance was to conjure, evoke, a real person of faith, in an ambiguous, relativist environment, which is the art world. Now let’s look at it. Feel it, if we could. Quite frankly, I felt envious of her.

GY: Envious because…

BTY: She had something that I don’t think I can have. That’s what I’m trying to find. She had a real, rock-solid… She was like that tree.

GY: That narrowness?

BTY: You call it narrowness…

GY: Narrowness, not in a pejorative…

BTY: Yeah, yeah, this relativist problem that we have of so many options, so much awareness of that which is indeterminate. Do I want to go back? This is where the toxic certainty question is, I think, like a lot of people. But, she had something like that tree. She also had this ability to be curious, though, curious about people. She wanted to travel and so on, but she knew where she was at. Do I know where I’m at? And do I have the kind of courage that I can go into a lot of different places, and be comfortable there, because I know where I’m at? ‘I’m a Christian woman; I’m a mother; I’m a black woman.’ She knew all that stuff.

Do I think when I go to…when I’m talking with Tere O’Connor and he is coming this close to saying that funders are too politically correct, they fund a lot of crappy ethnic work because they have to. Does that shake my faith? Is he talking about me? Is the success I have because a lot of good guilty liberals who have put me forward because they feel better? I’m a second-grade artist, but they put me forward? How do I deal with that insinuation, as we are trying to speak across the gap around—what is experimental art? What is good and what is bad? How do I let you come close to me to understand what I think is white-hot with meaning? And, how do we practice our various (and I use this advisedly) aesthetic creeds next to each other, which is what your question is about? And define ourselves as a community? How do we do it? What some of us do is say, you know what? I’m gonna build my thing, strong. And if I can survive through the next piece, that’s the only criteria that matters. If after twenty years (I started with the American Dance Festival in 1981 as an emerging choreographer, Molissa Fenley, Charlie Moulton, myself, Marleen Pennison and Johanna Boyce, we were the emerging choreographers in 1981) well, I’ve climbed out of the slime now! I’ve emerged; what does the landscape look like? Where are my colleagues? What’s going on? Maybe that’s the only vindication I can get.

When you asked me to do this interview, actually, you represent that world. You represent that enclave. Arnie and I started and I think you guys came a few years later. In 1980 we did Blauvelt [Mountain] at DTW and it got a lot of attention. When did Movement Research start?

GY: ’79.

BTY: ’79! So you [MR] were around already, but you weren’t…

GY: I wasn’t around. I got here in ’84. but it started in ’79 and [Richard] Elovich got involved in ’87, I think. And that is when MR started to shift, in my mind anyway, and started to say, there’s a broader view here that we can be addressing and bringing the political in. And there was a lot of reaction to him and after him when we did the Gender Performance journal and all those things. There was definitely a reaction by several artists, who…

BTY: …were losing their true religion.

GY: Yeah. And the true religion for them, I think, was Judson Dance Theater and ideas that came out of that. And why do we need to talk about sex and why do we need to talk about gender and why do we need to display all this publicly.

BTY: …and race.

GY: …and race.

BTY: …trying to be friends now.

GY: I don’t remember people saying—‘why do we need to talk about race?’ I think people were too afraid to say that.

BTY: Oh, they were afraid!

GY: I stuck my foot in my mouth several times, but not by asking the question that stupidly.

BTY: And there is one way to talk about it, show up and be that. Show up and bring your values of performance, your stories, your expectations of what an audience and a performer are, bring that to the stage and, well, and see what that group sitting there, what they make of it and how they write about it, what they do. There’s a lot of feelings. This is not of about blowing my horn, but now I understand how change happens. That’s, once again, those artists. You have as much freedom as you’re willing to pay for. So go in there and be yourself, now. Bring your issues into the discourse. Let’s assume there is a place for discourse, and that’s what you are trying to do. You’re trying to refine that space where discourse happens. It’s very possible to be operating in different rooms from each other. Have faith in the discourse, first of all. Have faith and courage in what you need to do from the profound depths of your personhood, not your artistic notions, but from your personhood. Now, bring that with your best craft, most researched craft, most historically acute—the understood craft—bring that into the discourse. And now, control your breathing enough that you allow there to be a response and an exchange. That is what we want. That’s worth fighting for.

GY: The sea shanty.

BTY: Mrs. McGrath? Did you know the song?

GY: No. I could tell that it was a sea shanty and a certain style.

BTY: Right, right. I didn’t know about it. I have Irish-American friends who said, ‘oh we all know that song, we used to sing it at camp, around the campfire.’ I discovered it from listening to old records of Irish singers, but also Pete Seeger singing it at Carnegie Hall. He says ‘here’s this song written about 250 years ago (I think he’s wrong and it’s less than that) and it goes like this, and when it’s over, when her son’s legs are blown off, and she is saying ‘Ted my boy, the widow cried, your two fine legs were your mother’s pride, I’d rather have you back the way you use to be, than the King of France and the whole Navy, Wid yer too-ri-aa, fol de diddle aa Too-ri-oo-ri-oo-ri-aa.’ Or, ‘foreign wars I do proclaim, between Don John and the King of Spain, I swear they’ll live to rue the time, when they blew the legs from a child of mine, Wid yer too-ri-aa, fol de diddle aa.’ Wow! Tough for a campfire song, right? But, he says ‘I hope we never have to sing that song again.’ The audience is… (clapping) yeah!!! And he says, ‘I hope we never have to write another song like that again.’ What year was that? 1962? When was it originally written? Our research says that it is Napoleonic era. So, mothers have been wailing about their dismembered and murdered children a long time. And that’s why, in Blind Date, when that song is sung, you see a [text that says] same old song. You know what I’m saying? Same old song.

GY: The duck? Or the ducks?

BTY: The ducks, that came from a story.

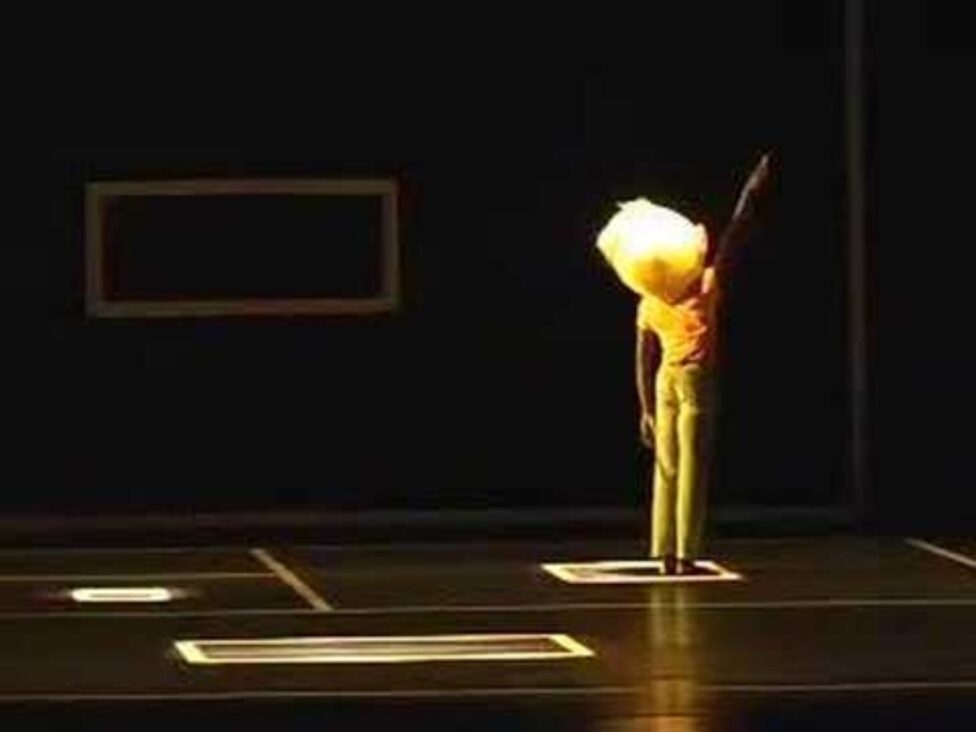

GY: … with the [duck] head, that’s you, I assume?

BTY: No, that’s Donald Shorter. Donald is dancing a solo that was originally for Malcolm Low. I was trying to make them all talk in the piece—tell me what makes you a patriot, what is your take on election, what have you. So, Malcolm said I want to do something but I can’t just speak spontaneously. I said what don’t you write something? As a matter of fact, if you want to talk about your experience but you don’t’ want to talk about your experience, why don’t you make it a fiction. He got really excited about it and he began to write these stories, really clever, strange little stories. Things that came from him, but also I said, (the character is called Richard) but what if Richard joined the army. And he said, oh, yeah! And he thought about it. So, now there is this teenage boy whose father tells him that he has to get a job and he gets a job at the Quack-a-Dack House of Burgers. And his job is to stand out every day, wearing that uniform and waving his arms saying ‘Quack-a-Dackburgers, Quack-a-Dackburgers, over here…,’ until one day, a man in a uniform showed up and he said, ‘we could use you, you could be of service.’ And Richard looked at him, and he didn’t wear a duck mask, he had this suit on with shiny shoes, he had a briefcase and obviously he is respected, and Richard signed up. Richard didn’t know what he signed up for and we say to the audience, ‘I know that you just met Richard, but on the day that he was supposed to report to duty, which uniform do you think we wore.’ And then the piece proceeds, kind of almost I Love Lucy style. They’re doing this army cadence. They’re doing these gestures, which are almost like a military drill, and he’s wearing his duck head, doing it with them. That’s the end of what was the first half. Then it comes back again with Shaneeka [Harrell] singing Otis Redding’s Security. Then the whole world becomes a kind of strange Quack-a-Dack logo, and we don’t see the mask any more, but everyone’s inside that world. And the ducks become… talk about assigning meaning to movement. Can you make the jump from Richard’s story to that symbol in the second act? That’s what I’m talking about, that trail of meaning. It’s very important to me. And, remember the commercial? You probably couldn’t see the commercial very clearly [on DVD]. There’s a commercial that Peter Nigrini did. And I told him it should be a commercial, imagine a cut-rate burger joint somewhere in the mid-west. You see that it has Paris Hilton, it has…

GY: I didn’t see that.

BTY: When you come to the performance, I want you to look closely at that. It’s shown twice. I think he did a real clever, tongue-in-cheek job. I told him, I want you to put as many subliminal images of sex and war in there, as they’re chomping on the hamburgers. My feeling, of course, is that’s what marketing is. You’re ultimately selling desire, and then (I don’t need to tell you this) the whole foundation of American materialism is based on a kind of corporate engine—an amoral corporate engine. The same thing that sells guns and sells war, sells hamburgers. So, that’s what I was trying to get at with that. Well, the commercial he made was strong. I mean, there’s a lot of kind of cheeky references to beautiful blonde women chomping hamburgers and ketchup, and people running to get hamburgers, quack-a-dack, quack-a-dack, quack-a-dack … and this little black boy selling Quack-a-Dack, burgers. But then it comes back a second time and I said to Peter, I think it needs to be stronger, even. Pornography is a multibillion dollar business in this country right now and it’s promoted by the likes of General Foods and people like that, own franchises, they don’t advertise it, but they do. Time Warner—big one, all your hotel porno stations are Time Warner. I said, now we’re going to lay into that heavier, and I think—violence. I said, why don’t you have more blood and guts, that ketchup should become more disgusting, why don’t you have real images from the war. Well, he did get around just the other day to delivering one to me that has a cum shot in it, two young blond girls getting cum shot on their faces. He actually produced the beheading last week, you know. It was strong, not to mention there’s already porno in the earlier one, and a woman giving a blow-job, that you couldn’t really see what was going on, just the motion, but this suddenly was in your face. The cum shot and the beheading. We showed to Lincoln Center, Nigel Redden personally wanted speak to me—‘it’s over the top. It’s over the top.’

GY: You decided to show it to them before just doing it.

BTY: Oh yeah! We thought as a courtesy. We’re talking high-… the dinner party… remember? Can you afford to?

GY: Right.

BTY: So we did, and just as I expected it, he said, ‘you can’t show that.’ We had it out—… we’ve been going at it for thirty years. He said, ‘no, you can’t do it, we’ve sold tickets.’ I said, we’ll put a sign up there. I said, ‘you know what, why are you saying this to me?’ He said, ‘well, you know, if you don’t like this country, why don’t you leave it, why are you always…’ Can you believe he’s saying that to me? I said, ‘what do you mean leave this country? I said, I think you should fight the good fight! You don’t leave…

GY: You change.

BTY: You change and you try to make change. So he and I are going at this and he’s sounding more and more like a Republican, and I’m sounding like a snotty, superior artist, and finally I said, ‘you know what, I won’t do it and I’m about to end this phone call, but I want you to think good and hard (this is the artist speaking) you can’t sort of do a tough piece, you can’t sort of live in this world, (you know, I got on my high horse about that) and I’m hanging up now.’ Hung up on him, right. Talk about biting the hand that feeds you. So we’re not using it. And I’ve been wrestling with that. We make our deals, right. We have to. And is that called maturity? Is that called…

GY: The question I have for you is do you have to, because certainly over your career there’s examples of where you didn’t, and has it hurt your career or, in fact, in the end, did it help it?

BTY: In the long run, you mean? Being called a victim by Arlene Croce, did it help or hurt?

GY: Well, not even that one, but…

BTY: You might say it helped!

GY: I mean more the decisions you make in your art, not how somebody else contextualizes it.

BTY: Well how that debate spun out of that. The debate. Did it help?

I said, ‘you know Bill, standing on principle on this one, making something so that next week in the paper there’ll be talk about how over the top it was and how the Festival is allowing this work, designed just to shock, to be there…’ To walk into that for artistic principle, I said, you know what, I’m not going to do it. And I wrote to him and I said, ‘you know Nigel, I really do think showing the second commercial stronger, would have sharpened the metaphor of the ducks, sharpened the meaning in the piece, deepened the critique. From an artist point of view, I say that. From your point of you, knowing that you have a large popular festival, I think you made the right choice. I don’t want to show any disrespect because ultimately, (this is the interpersonal part) I hung up the phone, I don’t like that activity. Like when I was on the front of the stage with ‘let’s fight.’ So, I did that, and sent him flowers and yesterday he called me back, said, but Bill, you didn’t have to send the flowers and so on. And he said, (he never apologized for anything), ‘you know, you can go public on this, if you like.’ Go public? Go public on this….

GY: Well, that’s another way to sell tickets.

BTY: Yeah, it sounds like… what was that?

GY: To me, that’s what that is.

BTY: I said, ‘I don’t want a big thing out of this, Nigel. Maybe I’ll put it on our website.’ But this is the question right now. Fight the battles that you stand the chance of winning? And then, what is winning about?

GY: Thank you Bill.

BTY: Yeah, thanks guys.