Benedict Nguyen: Critical Correspondence is interested in the artist’s process and the many facets that are involved in that. I was thinking we could start this conversation by talking about time as one of those facets and how your collaborative process has evolved over time?

Orlando Hunter: Well first, we started right here in our living room, just creating. It was really like improv all the time, just turn on some music and start dancing and our first performance was at a Brooklyn brownstone. What was it for?

Ricarrdo Valentine: It was like a curation they did every month where you didn’t find out the location of the venue until like the day of, or the day before. So the location was moved every month, and it happened to be in Clinton Hill. And I forgot who was the curator of it but it was like a friend of a friend who was putting it together.

OH: And so from there we were creating around mass imprisonment. We were looking at Mumia Abu-Jamal and how he’s still imprisoned. And that was from the 70s. How has the system changed, or hasn’t changed, since he’s been in prison? And that just kind of spun our interest into what other topics affected us or what other social mores kind of affected our lives. So we kinda started to move more into our cross cultural identities, with Ricarrdo being Jamaican American and me being African American and what stories do we bring to the table when we, you know, are seen on stage together, you know? They see two dark-skinned bodies but our histories definitely aren’t the same. As we’ve been going deeper in our process, our latest right now is how to survive a plague which is around the veneration of black bodies around the world who’ve been lost to HIV or who have been living with HIV and AIDS and looking for treatment, looking for solace. So yeah, it’s just kind of been like a deepening of our process, of our identities, and global, social, and economic issues I guess.

BN: With that opening up, bringing in more cross-cultural vantage points, how has that shaped the process of making work, developing work?

OH: Ricarrdo, you wanna speak to that?

RV: How has it shaped the work?

BN: Yeah, or the process. How you approach creating something, rehearsing something, or what language or ideas around, you know, that cultivation?

RV: Orlando can you kick it off and I’ll probably tag team it cause I’m just trying to develop my words?

OH: I think, cross-culturally, I mean, I didn’t come from a Caribbean background, you know? So adding Dancehall to our work, is also part of African American culture and actually our Hip-Hop culture has spun out of Dancehall culture so it’s interesting that, you know, at least going back to the roots in terms of thinking about how this aesthetic lives here and how, you know, Ricarrdo, you can speak more about how Dancehall interacts with our work or how we bring in contemporary Odissi or something.

RV: Mhm. For me, growing up in Brooklyn, New York and always living in an Afro-Caribbean neighborhood in Crown Heights, I just felt like it was important to go back to what I would say is my mother tongue of movement and to really contemporize it with someone who is not from Brooklyn, New York and may not even know the dynamics of that community. And that’s something that I’m always interested in bringing into the work that we create together. And just, understanding that complex identity that we both hold as two men together. I mean most of the dancehall vocabulary is very heteronormative and to see two same-gender loving men do those same movements in the public light, I think is revolutionary because often times, two men doing dancehall together is actually seen in darkness. And you don’t really get to see that all the time in the public sphere. So I think for us, to have that cross-cultural connection is really important because we have individual and collective stories to tell.

OH: Absolutely. I mean, it kind of brings me to our food. I think it really kinda became clear to me once we started to cook together and I’m like, “Oh, you didn’t cook collard greens growing up?” And he was like, “No, we didn’t eat collard greens. We ate callaloo.” Like, that wasn’t… you know?

BN: Right

OH: We don’t have the same food culture, you know what I mean? And that tells us something different about our people, and how we grow up and the foods we eat, so that was really interesting to me, definitely, thinking about our food. And also that’s been a part of our journey as well, connecting to land and food sovereignty and how does that work as a whole holistic practice, you know what I mean? If we’re going to be these thought-producers, cultural producers, how are we staying healthy, staying whole in our practice? And food has a lot to do with that. So that’s been a part of our journey as well. Developing food and herbal practices in our work, really working with the earth.

BN: So there’s scent and herbal work pretty intentionally incorporated.

OH: Absolutely. Food as well. In our work Afro/Solo/Man I cooked the audience collard greens and cornbread and they’re eating that, ingesting that, while the performance is happening or before the performance, or sometimes even after the performance there was leftovers. People like, “You got some more of that?” And I was like, “Yes honey, eat!”

BN: When it comes to the movement though, where you talked about how dance hall isn’t a part of your lineage in the same way it is for Ricarrdo, so in the composing of that, how do those ideas interact?

OH: You know for me, I have a very vast dance language so was coming from contemporary Odissi dance, coming from Afro-Brazilian, coming from— I grew up as a street Hip-Hop dancer, mixed with all this now Imperial Dancing— Ballet and Modern. It was at a time when I started to learn all these things that I was like, “Wait a minute, what is going on? I don’t know who I am or what is my mother tongue? What is my mother language?” I couldn’t… I was like “What is going on?” Especially in my comp classes. And so, then I was like “Forget it, I just have to go back to dancing how I dance.” And then I talked to a mentor of mine, Ananya Chatterjea, and I was like, “What am I supposed to do with all of this?” And she was like, “Use all of it at one time. Do all of it at once.” And now, for us, especially for storytelling, now we can craft with different vocabularies, you know what I mean? To make things, to say certain things, to give it certain flavors, to spice it up a little bit or cool it down a little bit. And I feel like these languages we know collectively between Ricarrdo and I, we kind of find this like, harmonious world when we started to create. And we were like “Oh yeah, this can go here and this can go here.” And so really just kind of like crafting, knowing the languages that we know and when to use them.

BN: Ricarrdo, does Orlando’s thought bring to mind any particular section of what you’re working on where this crafting and mixing has come together in an interesting way? Whether that’s… I’ll use ‘interesting’ on purpose.

RV: *laughs* Yeah, I mean for me I’m new to the contemporary Indian movement Odissi so that’s a new vocabulary that I’ve taken on as a dancer and creator so— sorry, trying to gather my thoughts. Yeah, that’s something new for me but I’m also teaching him I guess the traditional aspects of Jamaican movements and how they’ve transformed over time and finding different ways to use that vocabulary in 2017 and flipping it on its head. I think for me for Afro/Solo/Man, because it’s two solos in one, I was really thinking about how to get this kind of movement onto the popular stages and make it more exorable to other dance techniques that are out there. Because they tend to be looked at as ‘less of’ compared to ballet. And so that’s something I’m exploring more and hope to continue to push to the forefront of creating.

OH: I think there’s a section in how to survive a plague, at the end, we’re doing more contemporary Indian stuff and also in Sun/Son, that whole duet that we do?

RV: Mhm.

OH: That’s kind of like a hybrid of sorts. Yeah, even in—what’s that dance? Black Jones, that second section that’s more ritualistic and it’s more, uh, I don’t know, you could see like a hybrid of movement there too.

BN: Do you remember how those hybridities come to be developed?

OH: Well, we think of ancient movement, you know? Like a lot of things for us literally come out of our DNA. For us, well I can really speak for myself, Orisha movement came to be just because I’m a dancing, moving body and these movements just bubbled up and I just happened to go to Trinidad one time and all of these things make sense to me around movement and connection to the different elements and things of that nature. So, it is very intuitive, our practice. It’s kind of like, we’re not the kind of people that mill and mill over choreography, you know, it’s like “Oh my gosh, this isn’t right.” It’s kind of like, it comes out and we’re like—

RV: This is what it’s supposed to be.

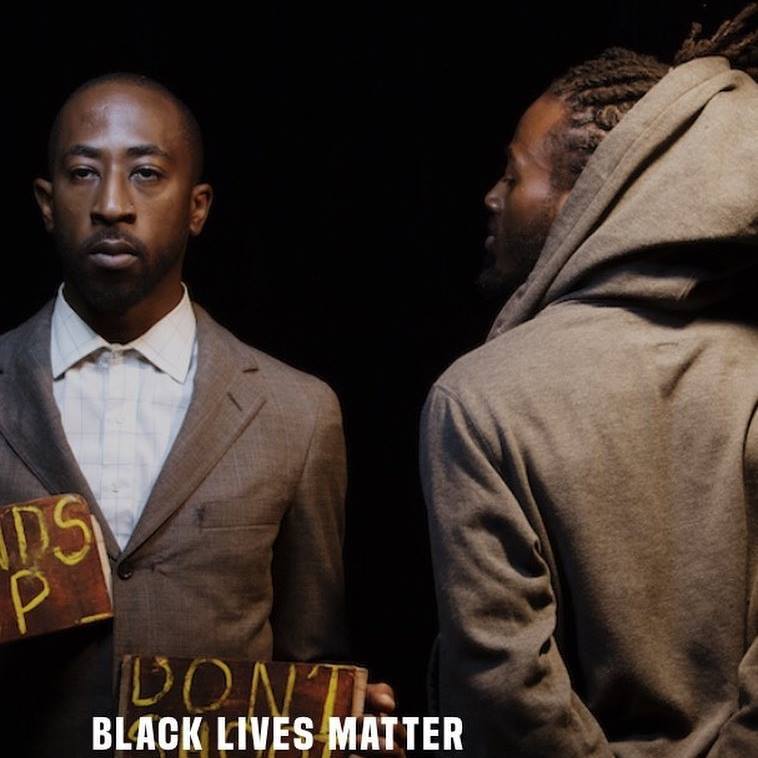

photo by Jaime Dzandu

OH: Yeah, and we can feel it. There’s one dance we created and were like “No. That will never be seen ever in life.” But other than that, now we kind of get this ebb and flow, you know what I mean? That dance was one of the first dances we created together. Now we know what we don’t want to create, now let’s create the shit we wanna create. I think that was really great in terms of figuring out our practice and figuring out our movement style and vocabulary.

BN: We may or may not have to go down this line but can I ask what did you know didn’t work about that piece?

OH *laughs*

RV: Um… everything? I mean, it was just really… the images we had in our head really did not come through in the performance and—

BN: That happens, for sure!

RV: We were like “Oh, this is gonna be so great!” And once we got that video back, it was like “Let’s hurry up and fucking delete that shit.”

OH: It was so stale.

RV: Yeah

OH: I can’t even—that’s the only real way I can describe it. I felt like I was watching it, I tasted it. And I was like “Ughh. That is stale.” We would never, ever do that again. And I don’t know if it was because… maybe the elements weren’t right, I just don’t know. It just wasn’t the work to be…

BN: …that you knew you were supposed to be making?

OH: Exactly.

BN: So it’s beautiful to hear how the dynamic has evolved where that it feels intuitive, there’s an ebb and flow, there’s motion to the creation. Ricarrdo, you also mentioned thinking about, I think you said the word translating? You’ve talked about translating ideas with a lot of history across time, translating ideas across space, from a living room to a stage. How does an awareness of a viewer, or what’s on the other side of that performance, how is that a part, or not a part of your process?

RV: How is it not? How is it? Um, I mean I don’t think I think about the audience too much. I don’t know, maybe I don’t really create the work for the audience, in my opinion. Yeah. I don’t really keep them in mind. I think I’m just like, I’m gonna dance or create what I wanna create and I’m just gonna see how people respond to it. And, let me see…

OH: There are aspects—because we definitely have audience participation in our work. We can’t say we don’t think about it.

RV: Yeah, I think it shifts space to space. Once we know what space we’re gonna be in, we give ourselves more room to improvise within our work and to really engage with the audience in different ways. And that’s just me pulling local references that come from other choreographers that I’ve worked with, like Edisa Weeks is someone who I think is really great at interacting or engaging with the audience in her work. And so, I’m just pulling these kind of ideas from choreographers that I’ve worked with and I really appreciate how they’re able to connect with the audience members, and so even for how to survive a plague, we give out these tea bags to the audience members as a way to understand one aspect of the healing process or self-care process. And so yeah. But I believe it does shift from space to space. Sometimes we’re in a proscenium setting and we’re not able to connect with the audience but I think we’re also rebellious in breaking that wall as well. *laughs* And figuring out new ways to perform the work. I love how Okwui [Okpokwasili] uses like non-traditional spaces but then also uses those kinds of aesthetics to bring it to proscenium stage so I’m looking at artists who break the rules in how to present their work.

BN: So when you were talking about translation earlier, it sounds like space is a key medium for how ideas move?

OH: Absolutely. I mean because like, for our first work, we were set up at FiveMyles Art Gallery. And that’s just one open space but we were like, “How do we really break up the space?” So we had—

RV: —and use the whole entire space at that.

OH: Exactly. The whole space. So Ricarrdo acted like the warden and there are these bars before you and there was only one door to enter the space so we used that as this kind of entryway. There was this office door that we used as a jail cell that people were able to come visit me. We had another friend of ours Brittany L. Williams, she had an installation there where she was handing out programs. We really tried to use the whole space and tried to see how the work inhabits that space, whatever it is. And I think where how to survive a plague was definitely a huge— actually, I think Afro/Solo/Man was the first kinda space we transformed, yes? In terms of creating installations, and having wall displays and like, then we just…

RV: So we premiered Afro/Solo/Man in Denmark, Maine [at the Denmark Arts Center] and it was like in this old barn house—

OH: Theatre house.

RV: Theatre house. Yeah, we actually had the audience sit on the stage itself and then we would be in the space a different way so we kind of changed their perspective of it. And then we also allowed them to get up and stretch and then move the performance across the street outside into the natural environment where we, you know, where people once performed before going into the proscenium stage setting. So I guess, just reversing the way the performance can happen in the environment.

OH: I think that’s something that we’ve been tapping on. I don’t know if we’ve really articulated, but we feel this need to kinda go back. We’ve been going to the earth, we’ve been planting things, we’ve been harvesting things. A lot of our practice is going back to these ancestral memories of how we worked in collectivity, how we shared in different ways, really kind of breaking down these oppressive structures that tend to break us away from the land. So for us, it’s kind of like this reverting back to ancient practices. My solo in Afro/Solo/Man is called Forgiveness: The Indispensable Truth and it looks at the degradation of the black family through food and I’m specifically looking at collard greens and cornbread and how my mother and grandmother would make these things. For me, I connected it to forgiveness. Love and forgiveness. My father was on drugs. My grandmother and mother would make these foods for him. For me, I was seeing love and forgiveness in this whole practice of creating these foods. You know, greens are a cleanser. What are these kinds of practices that we may not even see as valuable, but what do we— you know, someone like me— extract from our story that people may think they know? African American child having a parent on drugs and growing up in the hood, you know what I mean? People think they know something about that story but they don’t understand how someone like me would have come to understand love and forgiveness.

RV: And for me, the Afro/Solo/Man production, my solo was called Give Way and it just really looks at this idea of returning back to the land and having the space to strategize and think about your next movement before you go back out into the chaotic world. And really connecting to the color green and the greenery that you’re surrounded in there. Like most of the time, for creating that work, we spent a lot of time in New England area where it’s just a plethora of greenness everywhere and to have the natural resources serve as a way to feed us internally and externally. And connecting to the idea of connecting to, for instance, the hummingbird was something really important in my work. And how that can be ancestral as well and communicating with the underworld in that way? So, just thinking about how the ancestors were able to strategically find the oppressor. They’ve always retreated to the green mountains to really feed their body, their mind, their spirit before they were able to go back to the world and be victorious. So that’s how I like to use our practice, as a black artist in this field where we’re not given a lot of space to create and to strategize and to succeed or fail.

BN: Y’all are creating that space in the performance, in the manipulation of the space, the expectations that an audience might have about how things are organized. Thinking of Charmian Wells’ response of that New York Times review of the Forces of Nature show?

OH: Mhm.

RV: Mhm.

OH: Yeah, that’s really important to how people view the work. People have written some interesting responses to our work without being very informed on the cultural pulling, if you will, from where we’re coming from. Or the cultural references that we’re pulling from. I think it’s important if anybody is going to write about something and like publish it, you know, if you want it to be written well, you know what I mean? If you want it to be written like whatever then go off, write it by yourself, *snaps* Bow! Publish it, great.

RV: *laughs*

OH: But you know like maybe fact check? You know what I mean? “Oh, let me reach out to this artist and see what this is what they really was communicating with this piece. I felt this.” And it’s okay to write that! We want to know as artists what you felt. That’s why we produce it in front of an audience. We’re trying to make you feel… something! Whether that’s anger, sadness, discomfort, uncertainty, or something. As long as you leave feeling something, I think the artist is satisfied. And so, I think it really takes a really great researcher, if they’re a writer, to investigate a little bit, know what you’re going to see, you know what I mean? Have a little context. It’s also up to the artist if they wanna give that much context.

RV: And it also, I mean, the dance education system is not giving out the right information to future dance artists, writers, to write about dance. You know, they’re still stuck in the hierarchy of what kind of dance techniques are better than the others, and they’re not having the cross-cultural connection to other forms of dance. And so, when they do write something because they see a movement, they’re like, “Oh, it’s capoeira.” When it’s like, “No, I never did capoeira in my work and I don’t know where you got that from.”

OH: Mmh!

RV: It’s kinda like challenging to read something about your work which is like, you know, incorrect or off.

OH: It’s history making you know? That’s like leaving a trail. That’s lineage making. So how are we seeing ourselves a part of a lineage when our histories are written wrong? You know? That’s been a huge problem for the African American artist or [person] of color artist in general, you know. Having their histories written wrong by a white supremacist structure or a publishing company or a writer, you know? Or editor, for that matter. The editors want you to write certain things in or write certain things out.

Image by by Kiritin Beyer

BN: So moving towards how to survive a plague, what are some ideas you’re thinking about? You know, there’s so much history there, yeah? Deep lineage within AIDS broadly and dance around AIDS, specifically.

OH: I think for how to survive a plague, in 2017, it’s really important. A lot of the information that we are disseminating within the work isn’t widespread and isn’t even in a lot of the contemporary notions of HIV and AIDS. Especially how AIDS and HIV is ravaging the southern part of the United States of America. They have the highest AIDS and HIV count in the world. That’s crazy. If we’re deemed the superpower of the world and have all of this medical technology and things of this nature, why is a whole sector, subsector of our community here…

RV: Emulating the 80s of New York.

OH: Exactly.

RV: That’s like the language which we start to see in these health reports. They’re comparing Atlanta and Memphis to what it was like when the HIV outbreak was happening. We keep repeating this cycle. And that’s unfortunate.

OH: Is it even a coincidence that it’s happening so severely in a specific community, you know? All of the information that we had come about, that’s why we even named it how to survive a plague because we watched the movie how to survive a plague, and it was basically a lot of white men on there talking about how they were in the fight, in the struggle, trying to save they friends, putting money on the black market to get drugs and things sent here. And it’s like, “Well, if y’all were doing all of this for your community, what was happening over here?” Because we didn’t see any men of color in the video. Actually no—

RV: They probably walked by.

OH: Exactly, we saw a couple walk by the screen but they weren’t on there telling their stories. They weren’t on there giving their testimony about being a part of that time. So we had to do a lot of digging. John Bernd’s who—I mean, last year’s Platform 2016 [at Danspace Project]—why the whole thing came about. He has his work archived at Harvard University, which is how we were able to be recreating things and finding articles and all of this stuff. We’re trying to look up Essex Hemphill and Assotto Saint, and who else? Marlon Riggs and all the information is very limited. Luckily, I was actually working at Colby College at the time and I had access to their database and things so I was able to do some research, but I mean I guess you can go to the Performing Arts Library and there’s the Schomburg [Center for Black Research]. And we do have those resources outside the institution, but who’s going to know that? Who’s gonna know that? Like we can’t just google these artists, black men artists, who’ve created work or just existed during that time?

RV: And you might not even find that information at the LGBT Center. I know when I went to the LGBT Center in New York it was mostly white men’s narratives, you know? Our narrative is not really put on the shelves for us to go and grab. And that could be in one part because we’re mostly orators, but we also do— we’re writing more. And our stories need to be—

OH: And there was performances!

RV: And performances as well. And then who gets to— sometimes the family members of those African American leaders, gay leaders, their family— hold onto their stuff? So then we also have to find a way to negotiate with them to get that kind of archive. And that comes a lot with shaming, you know, cause your son is one: black. And he’s gay. And he’s HIV-positive. Who wants that information out? It wasn’t until after Alvin Ailey’s death, years later, we find out that he was HIV-positive.

OH: Mhm.

RV: You know, that was because his family didn’t want that in his accomplishments.

OH: Mhm.

BN: So how does how to survive a plague respond to that context? How has it evolved in the last year since Platform 2016?

OH: We expanded a section, the American section, which we just talked about in the southern part of the US. And we have an aromatherapy component that we’re adding this time that we really wanted to immerse people even more. You know, I feel like “how to survive a plague” is like the first real public AIDS/HIV dance since, like, what? Bill T. Jones’ “D-Man in the Waters” [originally premiered in 1989]? That’s been a dance that’s been circulating that deals with AIDS and HIV during that time. But like, what..

BN: What new work has been created since then?

OH: What new work has been created? No one’s talking about it. And we have. Maybe people are talking about it, but no one’s putting it in a dance and putting it on the stage and saying, “This is important. This is who we are. This is a part of our community and how are we dealing with this?” I think it’s something very important, especially because a lot of people don’t know how to take care of themselves with— whether that’s sexual health, mental health, or spiritual health. And I feel like how to survive a plague gets a lot at these nuanced understandings. We open up with Eshu and Baron Samedi, which are cultural deities out of the African spiritual practice. One from Orisha and the other from Voodoo. And again, that’s a cross-cultural practice but also there’s this connection between them in terms of their relationship to sex and sexuality. And just the genitals and how sex exists in the human world I guess. And we really try to touch on the spiritual component of sex too. Because it is a beautiful thing. Unfortunately we live in a society that shames sex, that is not sex-positive or even educates us on how sex really exists just in everything. So I feel like we try to open up some of these cultural taboos, if you will, with how to survive a plague.

BN: Did you miss that Ricarrdo?

RV: I missed everything.

OH: I was just talking about how to survive a plague and the importance of it now and how it’s one of the contemporary works around AIDS and D-Man in the Waters and maybe I’m ignorant to someone else who has created, I’m sure— actually Makeda Thomas created a work that I was a part of called A Sense of Place, which was talking about HIV and AIDS and Mozambique. She went and did a study there when she was getting her Master’s. But yeah, she created a work around this too.

BN: She was about to be calling you after this.

OH: Yeah, what you saying? Yeah, she definitely created a work and that’s from a woman’s perspective, yeah? Which absolutely is needed because again, there was no women in the whole how to survive a plague movie or when you’re talking about AIDS and HIV, it’s always filtered through this male lens but women are definitely affected by the virus as well and we bring some of that information into the work too. This is one of my favorite works right now. I really love to perform it.

BN: Anything you wanted to add, Ricarrdo, to that?

RV: I think Orlando covered it.

BN: It’s a lot of things. We’ll probably start to wrap up soon since it’s a lot to distill. Brother(hood) Dance! is addressing a lot of ideas in this one dance. You were talking about sex positivity and body positivity where those concepts have become accepted more readily, there’s racial dynamic to that. Aromas in a space— people have different reactions. Some people are very sensitive to scents. I guess, do you think about, or how do you think about all of these dynamics in conversation in the same space in the same moment?

OH: I feel like we work at intersections. At intersections there’s never just one thing and I think that’s what we’re trying to get at as a whole, as a society, trying to work with a more intersectional lens. When I come to a table, I’m not just black. I come to a table, I am black, I am a male, I am positive, I am all of these, you know? I bring all of these things and I’m not going to leave one thing out, as I was talking about with our movement vocabulary. Sometimes we’re going to use all of it and sometimes we’re going to distill some of it. But that’s for a particular story we’re trying to tell. If there is a particular grant, you know what I mean? You have to filter yourself through the lens that they are asking for. If they’re looking for a black man for a role, you fill the black man— doesn’t matter if you’re a black queer man or a black disabled man or a black trans man, you know? So I feel like we really work at the intersections in a hyper-sensory world because everything is coming at us quickly. How do we kind of bring that in but intentionalize it more? Because it’s something that human bodies are already wired to? So how do we use that same kind of wiring to infuse some kind of different information?

BN: Ricarrdo?

RV: Can you repeat your question?

BN: To jump off of Orlando’s response a bit: The work is grappling with so many questions. So Orlando was talking about intersections of identity, but there are a lot of intersections around space, time, history, sensation, as well? So, I guess I’m curious about the ‘how’ of that? I’ll bring in another word here: Maximalism. I don’t know if that’s one that is related to your thinking at all but…

OH: Maximalism? What is that? Using lots of thing at once? Maxing out the space?

BN: Yeah… doing the most.

OH: Yes! Doing the most! *laughs* I think yes! I think that’s what we do when we go into the space. We definitely do the most.

RV: I mean, we gotta bring everything. We can’t leave anything behind because every piece is important. And so, shit, if that’s gonna be Maximalism, I’m down for it.

BN: I don’t want to impose that label if it’s not one that—

RV: I think that’s where we probably we live. I think that’s where we live.

OH: But also, it depends on the performance. Because sometimes we’re like, “Well, we can’t be doing all of that shit. We gotta bring it back.” And so…

RV: Right, but I think we go all the way. I think we put everything in. And we start to say, “Okay, what needs to stay behind in order to tell the story?” That’s how I like to move. I like to go to the far extreme of the spectrum, whether that’s minimalism or maximalism. And then I try to figure out the in-between then.

OH: Definitely.

RV: I am interested that we’re bringing the aromatherapy into this work the second time around, because you know sometimes, you go to an art performance, you’ve fallen asleep, and the scent might wake your ass up and get reconnected to the section. So… *laughs* I mean, yeah, what is it like to use all of your senses while watching a work? Most of the time, you’re just listening or seeing. But to smell and to touch, or to taste, is something that we need in performance.

OH: Mhmm. Some people say we talk too much, but….

BN: Never enough.

OH: As the dancer now we have a lot to say, you know? Especially because people have deemed our art form as unintelligent or ‘less than’ in a professional world. We have a lot to say and then for those who are a part of the knowing of dance, the Dance World, who will probably say, “Well why do you have to talk?” I think it’s all about creating accessibility for the audience, you know what I mean? It goes back into that idea of— if you create for the audience or not— for me, I think it’s really about legibility. If I want you to understand me, then if I have to just be like, “I * need * to * say * this * to * you * like * this. * And * this * is * what * it’s * going * to * be!” *taps table between each word* Then I got my point across, bow! And I can go on to some other abstract shit. *laughs* But if I’m going to say something that I want to say, I need to make it clear so that I’m not trying to dupe you into something.

RV: Mhm!

OH: I’m not trying to do anything else but tell you exactly what it is I’m trying to say. I think what I’m trying to say is important. I think you hearing it is important, whether you take it with you or not, long as it just came across to you and you’re like “Oh, that was interesting to think about. Hm… moving on.” Or, “Damn, now I’m gonna change some shit.” You know? However that happens, I still transmitted the information that I felt was necessary and important for that time.

BN: Any thoughts to round this out? Anything you want to share that you haven’t yet? Ricarrdo or Orlando?

OH: I’m excited to perform it again. Especially now, it’s kind of outside of the context of the Platform 2016 HIV and AIDS whole curation. And now, it just lives as its own…

BN: Own work?

OH: Yeah, as its own work, as its own idea, as a continuing.

RV: And it could be in any curatorial platform. *laughs* I mean, I only say that because there was this one writer who felt that, you know… I guess the work only serves in the conversation of HIV and AIDS but I think the work can be so intersectional in many different ways and it doesn’t just have to live in that kind of platform. And I’m just really excited that perhaps more queer POC folks will be able to see this work. I just think about the feedback that we get from our peers who are queer, or same-gender-loving, or probably dealing with HIV and how excited they are to see a reflection of themselves in our work. And so I’m just really, really appreciative and scared to show the work because my mom hasn’t seen it yet. And hopefully, one day she will.

OH: My mom has.

RV: I’m looking forward to that. I’m looking forward to continuing to show what two dark-skinned, black men can look like and love and enjoy trying to figure out how to survive together and probably, individually. And to also really just lift up the voices that came before us. And we’re adding on to that lineage.

OH: All of that good stuff.

*both laugh*

OH: It’s just good work. I really believe in the work. I mean, I guess if you don’t believe in yourself then, like, nobody will then it’s kind of like of course y’all gonna be like, “Oh it’s great.” But I really think it’s a great work and I really hope as many people can see it as possible because I think it changes you. It changes your idea about how people are viewing these bodies moving and experiencing together.

RV: And it brings up, I think, when we had premiered it last year, I mentioned my previous partner’s name. His name is Renny. You know, there were a couple audience members who were like “Oh, I had a friend named Renny. And he also passed away from the virus.” And so it just brings up those really good moments of friendship that they may have had with the person.

OH Absolutely.

RV: And so you really reflect on then and now. And to really give life to those names again.

OH: Yeah, we have a video that plays and there’s just a scroll of names that are just happening while it goes and lots of people are coming up to us after like, “Oh, did you know that I knew so-and-so?” And “Yeah, oh yeah, that was so-and-so, that was my friend.” Or, “I used to take class from this person.” And so all of these stories just start coming out about these different people. The most— I guess, I don’t know if it’s haunting— or, I don’t even know… auspicious should I say? Was Al Perryman… while we were creating this work, this woman… we were at, what’s that farm?

RV: SPACE on Ryder Farm?

OH: SPACE on Ryder Farm. There was another artist there who was doing work and we were just talking and she was like, “Do you know Al Perryman?” And we was like “No.” And she told us all about her experience with Al Perryman and how she felt like a reincarnation of him. She lived on the same block as him. She went to his dance school and all of this and he passed. He was one of the first in the dance community to pass of the virus and people were just like, “What is going on? What is happening?” And come to find out Al Perryman was teaching another woman that we knew and so this whole life of Al Perryman that we knew nothing about as a dancer or in general, we didn’t even know who he was, you know? And so, he came out of the unknown to us. And so that was really beautiful. So we kinda knew that this work needed to be done. That’s why I really am excited to just share it, to just get it out. I mean, each time is kind of nerve wracking. Just because one: it’s very erotic. And we were working with the idea of eroticism within this work, looking at Audre Lorde’s… what was that?

BN: Uses of the Erotic?

OH: Yes. And thinking about that, what does it mean for us to be sexual beings? Our sexuality in the United States of America is always either stigmatized, it’s over- and hyper- sexualized. It’s never seen as a function of love. So like, what does it mean for us to love intimately? I think that’s what this really all gets at. What does it mean to love intimately?

BN: Any last thoughts Ricarrdo?

RV: Nah, I’m good. Shout out to Brooklyn. *laughs*

OH: Shout out to Brooklyn.

BN: Love it.

OH: Thank you so much.

BN: Of course!

OH: It’s always nice to be able to share. Cause we’re fairly new too, so people are always like, “What are y’all doing?” When people see our work, they be like, “I don’t know what I just saw.”

*laughs*

RV: They’re really interested and they’re just like, “So… how do I support this thing?” So yeah, I mean, I’m excited about the newcomers coming to see it. The new eyes.

BN: Can I share some thoughts I’m thinking about at the end?

OH: Yeah.

RV: Absolutely.

BN: I think what I’m really excited about in terms of dance and performance being the vehicle for this is: you’re mixing explicit things in terms of naming things outright, people’s names. But there’s still so much room for interpretation and subjectivity because as you’ve said, those names can mean so many different things to so many different people. A gesture. A look. The way you’re saying it… gives a lot of depth. The most.

OH: The most! *laughs*

RV: *laughs*

OH: We’re gonna be known as those dancers. Doing the most.

RV Child. I would love it. Like “Yessss, okay!”

OH: Doing the most in a good way, honey.

BN: Legible and how can you read it at the same time when it’s that many things?

OH: Exactly. One writer said she can’t even write about the work. She has to see it multiple times because she wouldn’t even be able to do it justice to write about the work. I mean she attempted and then she got it wrong, but that’s a different story.

BN: Name is not being named at this current moment.

RV: We ain’t gonna shout them out.

OH: Until it’s time! *laughs*

RV: Maybe for the dual memoir, we’ll probably shout them out.