All photos: Courtesy of AUNTS

Levi Gonzalez: So, let’s start simple—like a little bit of the history of AUNTS Bash—how did it start, where did the idea come from, and what is it?

Jamm Leary: AUNTS started because Rebecca Brooks and I wanted to see more dance, and we wanted to curate shows, and we wanted to make shows that we wanted to watch—you know, in a very specific way. Personally, I had been thinking about this for a long time—about curating shows. It’s something I’ve always been interested in. I had put together a show at this art gallery, CANADA, in January 2004, which was great in a lot of ways, yet I think that I didn’t really know how to go about it. My idea for CANADA was that we would all share ideas and make pieces together—not the same piece, but that we would build the pieces together. We would have our separate worlds, but the worlds could and would interact. The ideas would (hopefully) overlap, and sometimes we would rehearse at the same time in the same space to add to the overlapping nature of the entire evening.

I think this was probably a reaction to being Sarah’s [Michelson] assistant at the time, because she is so insistent on being secretive and mysterious about ideas and she’s so possessive over ideas. It was exciting being a part of that in a certain way, but it didn’t make me feel good, and it seemed to torment her a lot of the time. She had a really big thing about stealing people’s ideas and so CANADA was a little bit of a reaction to that.

Then, in Spring 2005, I was working on a dance piece of my own where I just wanted to do, not a work in progress, but what I called a “trial run” of it. I was trying to find places to do it and I did it in all sorts of weird spaces.

Levi: Yeah, I remember that, actually.

Jamm: I did it in the hallway of this old firehouse, and on a roof, and I forget where else. But, most importantly, I did it at a place called The COZ. I was just asking around in dance class if anyone knew any places to perform, and Rebecca was like, ‘Oh, my girlfriend has this really great space; bands play there and it would be really good for dance. I dance around in the kitchen and the living room there all of the time.’ So, then I did a little thing there and it was a really great space; it was really amazing.

The summer following that spring I was away in San Francisco— taking a break from NYC, hanging out with the parents— and I decided I wanted to put together some curated events in NY that fall. So, I called Rebecca, and we just started putting together events, you know, a month before they started happening and we just kind of threw them together, and we threw the parameters together. It was really just basic instinct for what we wanted in terms of the performance situation that we are giving people and what kind of performance we want to encourage. And so that’s how the Fall Bashes began.

I was just writing out a little résumé for AUNTS, and totaling all the people that participated in it, and it really was kind of a free-for-all. We had something like seventy-six performances [laughter] and fifty people performing; some people would do repeat performances, and sometimes in different shows.

Levi: One thing I think about is the curating of AUNTS, and one thing I notice is the volume. It kind of sets it apart, that they are sort of marathons: here’s fifteen people doing a show tonight, you can come or go as you want. I always feel like there is something kind of democratizing about it. It feels sort of generous, like it has got its hands in a lot of places, and I’m curious if that idea of curating what you wanted—and you said wanting to watch things in a very specific way—I’m curious about what that is, and if it’s evolved as you’ve continued to do the AUNTS bashes.

Jamm: It definitely has evolved after the first set of the Fall Bashes, but, initially, it began as thinking about what an audience member is, personally and objectively. I love talking at shows (Rebecca always gets really mad at me for it). I like having the ability to watch things how I would like to watch them and to act how I feel like acting while watching a show, to have the opportunity to leave or come back to it. Going into a traditional theater, you don’t get that. You are stuck in a chair, you are confined, unless you are specifically not. Dance is not confined, and so I thought that it might be appropriate with dance to have an audience that can move around as well, to create movement in the entire show.

So we thought about rock shows, and we thought about art shows—but art shows are a little sterile, in a way—and went towards a place where people could walk around at all times. We encouraged people to drink and to socialize, and to be excited about watching dance, to talk with friends while the dance was happening, to be excited about being an audience member, and to be excited about the fact that they have the choice to watch or not to watch. Furthermore, they had the choice of what to watch, because there were sometimes multiple performances happening.

We tried to give both the performers and the audience a lot of possibilities. The performers could do as many performances as they wanted, as long as they negotiated it with other performers in that evening. They could do the performance for as long as we had the space, if they wanted to. They could decide how they wanted the audience to be, they could have the host make an announcement about how the show was supposed to be watched, or not, or they could have someone else make an announcement. They could do it in whatever corner or center space, or wherever they wanted to. Things were left up to them, and, in it being left up to them, we tried to give them some options. Like, we really encouraged people to use the lights we provided, whatever basic, fucking lights—clip lamps, house lamps, bare bulbs, colored bulbs. During the tech, which was always a few hours before the show, we really stressed that lights were one thing that dictated a performance, and it was up to the performers to think about how to light their own show—there was no lighting technician making decisions. If you wanted anything to happen, it was up to you.

Levi: It feels like there’s an aesthetic, even, to AUNTS Bash. Not necessarily that everyone’s making the same kind of work, but that the work all exists in a certain kind of context, a certain aesthetic.

Jamm: What is the aesthetic that you have seen?

Levi: There’s a little bit of a D.I.Y [Do-it-Yourself] aesthetic, and I totally see rock show, and the informality of that, and that it’s a very social environment. It’s an aesthetic that, to me, is responding to some sort of dissatisfaction with the traditional dance performance venue—particularly, I think, in New York.

Jamm: Yeah.

Levi: I’m interested because I’ve been reading the new email petition and there’s kind of a little manifesto at the bottom.

[INSERT] AUNTS is about having dance happen. The dance you’ve already seen, that pops into your head, that is known and expected and unknown and unexpected. Dance that seeps into the cracks of street lights, subway commotion, magazine myth, drunk nights at the bar, the family album, and the couch where you lay and softly glance at the afternoon light coming in through the window. AUNTS constantly tests a model of producing dance/performance/parties. A model that supports the development of current, present, and contemporary dancing. A model that expects to be adopted, adapted, replicated, and perpetuated by any person who would like to use it. Where performing can last five seconds or five hours; never a “work in progress.” Where the work of performing is backed by the “land of plenty” rather than “there is not enough.” Where the work of AUNTS defies the regulation of institution, capitalism, and consumerism. AUNTS is about being gracious in this world. Thank you.

Jamm: [Laughs.] I know. We [Biba Bell, Erin Sylvester and Jamm] wrote that for the Contact Quarterly and I just stuck it on the bottom of an email for one of the shows, and I’ve gotten a bunch of comments about it—it’s really funny!

Levi: I like it because it’s a little provocative. It shows that AUNTS is about something, but it doesn’t feel like it’s telling you what it’s about, but that there are ideas that are being addressed.

Jamm: Yes, though there are definitely ideas being addressed. I think that the Fall Bashes (fall 2005) were really just for us, the people that were producing, and to see what the possibilities were—what the highlights and strong points of this type of model are, which I found to be that the performers had a lot of options and that there’s no pressure to do anything except to perform. They got to be social with the audience, the audience got to be social with each other, and the performers and the audience was comprised of many…it was definitely a dance-dominated crowd, but it was also made up of a lot of other people. So, the social atmosphere was really great. I loved it and I think that other people were interested in it. It became a very social gathering, a way to meet people.

We really discouraged “works in progress.” Initially, in the email that we sent out to performers for how things were going to be run, we really specified that this is not a works-in-progress show; that one of the few things that we do not want is a work-in-progress and just to think about it as being a show. So many times in New York, you go and see these works-in-progress and it’s a justification—it’s about, ‘this is what I have right now, but the costumes aren’t quite right and I haven’t had enough time, or this isn’t fluorescent lighting, and this is time just in a studio.’

What are you showing then? Why are you showing? I just don’t understand, personally, why people show works-in-progress. I think that it’s great to show—I think “showings” are great—but I think the idea of “work in progress” is awful.

Levi: I think it validates a certain model for what theater is: the big theater that is presenting you is the “real” gig, and everything else is less important. When I go to an AUNTS show, I feel like that’s…like it’s really fucking with that. The kind of performance that happens there—and I think that it’s gotten more clear the more they’ve happened, because the artists now understand what the context of the work is better than when it first started—I feel like it’s the kind of work that can only exist in that kind of environment. You know what I mean? That that’s part of its strength—that it’s not in a theater, that it’s in a crowd, and in someone’s house, or The Event Center… [both laugh] …or in a space that’s not a neutral space.

Jamm: It’s not a neutral space. It’s not a studio. It’s not a place with bare floors and bare walls and maybe a few folding chairs. It’s a space that you are affected by—your performance is significantly affected by the situation that you’re in, and people, and the space, and the location of the space—your own choices in that. It’s not distanced. In a studio there is great work to be done in terms of the physical body, and what can happen when you are really working with the body (and it allows for very few distractions when you are working in a bare studio), but, there are a lot of other things out there that people could be aware of, namely, other people and other spaces. Like walking on carpet or like dancing over by the bathroom, and not dancing in this pristine space.

I feel that watching dance in New York (even downtown dance in a black box), there’s this striving towards being like a television set. It flattens out the performance. The Joyce is built almost like a flat screen TV. Maybe that’s partially dance striving to be more acceptable, and more like the other forms of art and entertainment. It’s so great when people are dancing right by you, like going out dancing, there’s this real sort of primal energy to it that you don’t get to witness when it’s on a stage and so far away. Not that that’s not great—to see a dance piece on a stage can be a transforming experience.

After doing some administration for dance people and watching the very minimal money that trickles in to people that are well-regarded in the field, and how they had to struggle personally and artistically to make work, I thought, let’s just look around and see what we have in excess and ask for things like space, just so we can do something. Because, if you don’t have any money, then you might as well just do something.

What is that ladder that you go up, and what happens when you get to the top of that ladder? There are so many people that climb up this ladder that doesn’t really lead anywhere; it doesn’t lead to any sort of stability or satisfaction—it’s a cliff, you can jump off or turn around or just stay there on the edge of the cliff. The NEA died and people are applying for grants that are $5,000. When you think about an independent film being made, $100,000 is a tiny, tiny, tiny budget. So, if we really don’t have anything, let’s really think about it that way. Let’s just do something that is completely what we want to do, kind of underground.

Levi: There’s something about it that’s a little bit celebratory too. It’s introduced me to different people in the dance community that I probably wouldn’t have hung out with.

Jamm: We’ve had some couples get together—two dance couples, that I know of, met at AUNTS. They were dancers orbiting in slightly separate circles and they met there, and that’s actually the story that I am most excited about—that people are meeting each other and hanging out. I know that both of those couples (well, now it’s not that many months later) are still together. I was really happy about that.

Levi: That’s great. We talked up at the Lexington residency about the state of New York City in terms of….when I first moved here, Movement Research was on Third Street and Avenue A, and there was a coffee shop and everyone would hang out after class and get to know each other, and it seems like, more and more often: a) those spaces don’t exist anymore—the coffee shop you could sit in for three hours is now a restaurant where you have to spend a lot of money to sit at a table, and: b) that people don’t have time anymore to hang out with each other, because everyone is working so much to pay their rent. I really feel that it’s partly economic and partly political, and that one of the things about dance to me is that it is a communal art form—it’s about being inspired by your colleagues and talking about ideas, and hanging out with them in different ways. It’s not just a formalized relationship. To have that idea be kind of pulled out to the front is really satisfying, for me.

Jamm: Yeah, the social aspect of it was one of the goals. To introduce dance people to each other, because otherwise we end up in these enclosed circles of who you know which defaults to people who you went to college with and you are still working with four years later. Which is great, but it is also nice to have some mixing. Now, I’m leaning more towards looking at cultural economics, which has to do with consumerism and guilt for asking for things—always feeling like you have to buy something, instead of any sort of trade.

Levi: A barter economy—that’s where the boutique…

Jamm: …which is what happened with the shows following the… I’m always trying to figure out ways to better the model. I wanted to have everybody bring something to it and take something from it—not that they already weren’t, but I wanted to be very clear. Originally, we put money into it and we were paying for some liquor, we were getting some of it donated, and that was kind of a lot for us, who also have no money or space. So, we decided that we didn’t want to have any money exchanged, but that we would have people contribute, for their admission, to either the free bar or the free boutique—they would drink at the free bar, for free, or they would shop at the free boutique, for free. Or both.

We have this great free boutique director, Michael Helland, and he got really into his role. He would have fashion shows with all of the stuff that came in. Some people would bring big bags of stuff and other people would be like, ‘What? I didn’t bring anything’ and they would take off their belt, and give us their belt. Isabel [Lewis] gave some chapstick one time, and it ended up that Eleanor [Hullihan] really wanted it. So, it was this exchange of material goods within the dance community. Like, I went over to my friend’s house and I was like, “Oh! Those are my shoes!” [laughter]. And she really loves them. Isabel has Janet Panetta’s hoodie…

Somehow, that was to promote this kind of new cultural economics—ways to bypass our need for so many material goods—how you can actually live, because there are so many things you can get for free if you actually know about them and ask for them and you figure it out. I mean, most of our space we got for free, and great spaces, you know?

Levi: It seems related to the initial idea of frustration with the money situation—that it’s a financial system where the artist is at the bottom trying to navigate to be able to do their work. Then, the value of work is that which is presented at the theater and not the day-to-day experience of dancing, in a way. I also noticed that a lot of people that are in AUNTS are not necessarily identified as “choreographers”—they are more identified as dancers, a lot of the time. I could be wrong, but some of them aren’t even interested in becoming “choreographers”—that something about the act of dancing becomes central.

Jamm: Well, yeah, people want to become choreographers—that’s great. But, we also wanted to have people just do something, because you learn so much from trying to present something of your own. In really selfish terms, I wanted to be inspired by the work of my generation, and I felt like this is the way that I am most effective in doing that—not by trying to pursue my own work—and that informs my work and how I do the AUNTS events, and vice versa, but I am really interested in what other people are doing.

So, after the Fall Bashes—they went well, they were fine, people had a good time, and there was some great work that was happening; it was a beginning of something—I talked with Rebecca about what the possibilities were for AUNTS. I felt like we needed to have a vision of it and I thought that I wanted it to be a model that wasn’t based on promoting and producing it, but it’s something that people could take and adapt and adopt and use for their own needs. On my end, I’m constantly trying to rework that model, but also have the openness of—you can use whatever you want from this exchange, whatever it may be for you. My friend Biba [Bell], in San Francisco, put together this festival, alongside this big dance festival there at the Yerba Buena Center. She did her own, called “Other Dance,” and it was pretty much based on the AUNTS model. And it was great—it was great to see that the model can actually sustain itself and be reworked in a different context.

Levi: In a different city…

Jamm: Yeah, totally different city, totally different people, and it was great. Biba did a fantastic job putting it together, and added her own things (and in San Francisco, of course, there are really large spaces). So, that’s one of the things that made me really happy. AUNTS is not…I mean, of course it’s going to be associated with me and Rebecca (though now she’s not doing it), and other people that are involved, but it’s really about this thing that can sustain itself…it’s not such a ‘mine, mine’ or ‘I’m the host of it.’

Levi: I always feel like it’s AUNTS Bash, and though we associate people with that, it seems kind of fluid, in terms of who’s actually…

Jamm: Growing up in San Francisco with earthquakes, I was brought up with the idea of architecture in terms of fluidity and withstanding the earth moving. I think when I was ten, I went through the earthquake in ’89…

Levi: The one where the Bay Bridge collapsed, one on top of the other? I remember that.

Jamm: …so there was a lot of talk around about how buildings were constructed, specifically for that region, which I think heavily influenced my concept of how to build a structure and is very applicable to this thing that I am currently trying to do where the strength of the structure lies in its flexibility.

Levi: Flexibility built into the structure… I want to talk about what is happening right now with AUNTS, because there is an idea about letting go of curatorship, in a certain way. Could you talk about that?

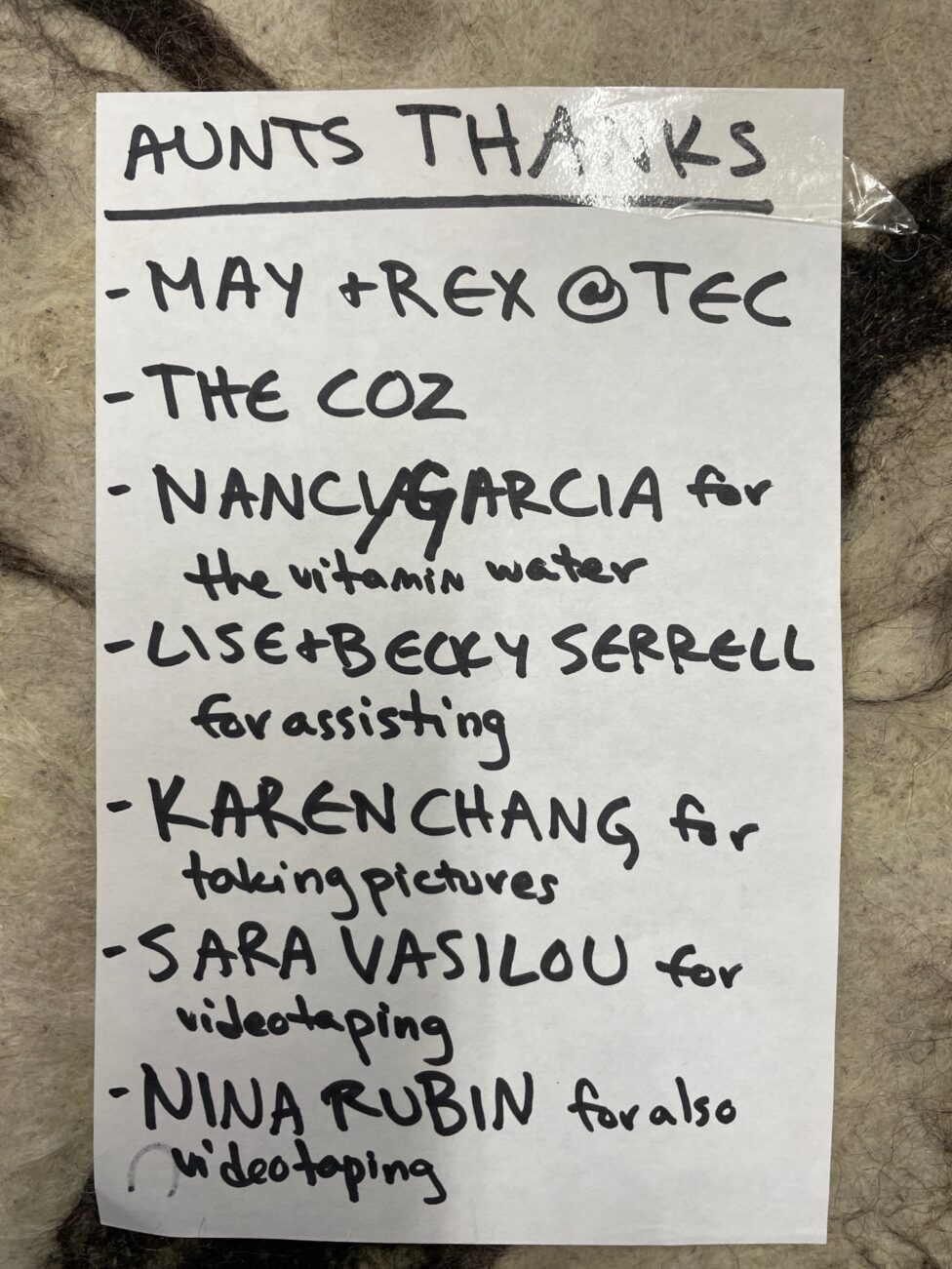

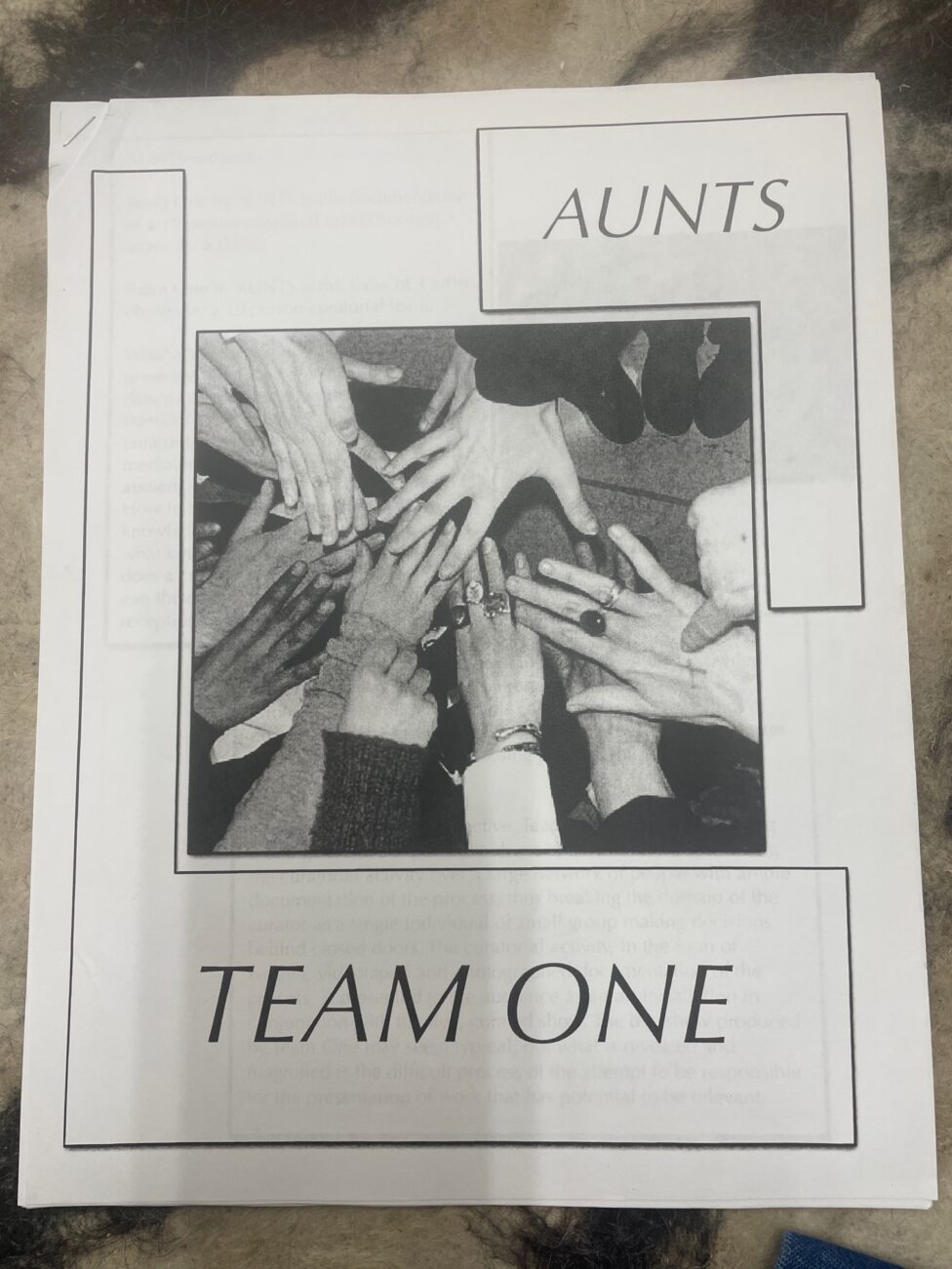

Jamm: I think that I was influenced by my job at the fashion PR company, with our designers, who are emerging luxury designers, where to make money they will design a line for bigger companies—like Bing Bang Jewelry designed a line for Marc Jacobs and Philip Lim 3.1. So, thinking about that, and also “Team One,” which I originally wanted to do in the Spring 2005 and which was a very large curatorial team with some structure and people would vote and the team would meet a few times and would talk about work, and they would have to bring people to the table and then people would say “yes” or “no” and there would be some voting process.

Levi: What is “very large?”

Jamm: I was thinking thirty people. So, the curatorial process would be this whole group meeting, we’d videotape it, and then we’d have four people that we would have picked in the end to show work for a weekend. But, really what we would get to talk about is the work. Every team member would have to propose and defend work they would like to present with no videotape, live showing, or images. Because I felt like, yeah, the AUNTS Bash is a free-for-all, and that we did the panel, which was a grandiose vision, and then we did these more dance-party, performance things, but I wanted to concentrate on the work (which was what I thought about for Team One), and talking about work, and just getting people to think about work. Anyway, that didn’t happen, so the follow up to that was that I wanted to have people, individually, think about the work that was around them, and who they would want to have represent them in our shows.

So, we talked to people about doing the first show and we put together a whole group of people. We said, okay, for the first show you can either do the show, or have someone represent you. For the next show, if you had [already] performed, then you have to have somebody represent you. If you had [already had] someone represent you, you had to have the person that represented you pick another person to represent them. So, basically AUNTS would only have reigned over the first set.

When I sent out emails about it (to ask people), some people got it and some people really didn’t. I had to call people and explain to them what the idea was. It’s a concept that happens in the fashion world, all the time, and it happens in the art world, too, where they have artists curate other shows but, maybe in dance it’s a more unheard of concept? I don’t know. Because, I felt that everyone was kind of scrambling to do their own work, without even thinking what was around them—the work that was around them.

Levi: I think the idea of curatorship in general is absent in dance; that people don’t curate so much as present. It’s a different structure.

Jamm: I think you’re right. I think that Miguel [Gutierrez] does a really great job curating—I don’t know if he’s doing it this fall—but there’s Chez Bushwick; I think that the stuff at The Kitchen…Miguel is somebody that, he’s really into his own work, but he has great sensors for what the work is around him, and for encouraging work around him that is not necessarily following in his footsteps—which I really admire. I think all of the people that he has picked are fantastic.

Levi: Right now, with AUNTS Bash and Shtudio Show [Chez Bushwick], and now Ambush and the thing that Chase Granoff and Chris Peck do at the Chocolate Factory, Live Sh—, it seems like there’s a whole movement of younger artists wanting to curate, actually. There’s always been some artists’ curatorship (even in the dance world), but now it feels like it’s a whole generation of young people that are saying from the beginning, ‘We want to curate, we want to understand what that’s about, we want to face those decisions; [it’s about] making a statement about what work is affecting us, what work is exciting us.’ That, to me, is really exciting and that’s why I’m doing these interviews.

Jamm: Yeah! It is really exciting, I think…

Levi: …and I love the idea of giving up control, too, in relationship to that.

Jamm: That’s why I wanted to extend it even further. Most of the people that I’ve heard about that are representing our first group, I don’t even know! It’s so great! It’s funny, the questions that people ask: ‘does it have to be dance that represents me?’ or ‘is this person okay?’ It’s funny that people have a little bit of apprehension or confusion, in terms of the concept of it. Like, I would send out an email and say, ‘I’d like you to do the first show and have someone represent you on October 18, or whenever, and then they do the next show, etc.’ I would get an email back saying, ‘I can only do the December show,’ but I had stated that, if you can’t do the first show, you can have someone represent you—I’m just asking you to do the first show, I’m not asking for these later shows. People didn’t know how to, exactly, deal with it, which was interesting. But then they got really into it. I also tried to encourage people to represent themselves, like, “Marc by Marc Jacobs,” which has not happened yet!

Levi: Oh! I see what you are saying, yeah.

Jamm: If you want to do all four shows, you just represent yourself in all four shows.

Levi: It’s about messing with ideas of authorship.

Jamm: It goes back to my entire original idea with the CANADA show, with this crossover of ideas. It’s so applicable now, because ideas are coming from everywhere.

Levi: One thing I’ve been noticing—and you mention rock shows or art shows, and just doing these things in alternative, or other venues, not dance venues—that there’s a desire with dance artists to not have their work defined only as dance. Like you mentioned, the curiosity about the world around you, and the people; and music and fashion and film, or art. There’s an awareness of other things—and politics—it doesn’t even have to stay in the culture realm.

Jamm: [agreeing] No…it’s political. Our situation is partially because of politics (because of culture and politics); the situation that dance is in, the way that dance is made right now, and the way that it’s thought about. There’s this whole intention of what dance is—which is just movement, moving bodies—put into a tiny little box; it only can be this, it only can be packaged a certain way, it can only be a certain way. And, you have to make money from it. Of course, people have to survive, I definitely understand that.

Dance is such an amazing form because you’re taught to look at unseen relationships, systems and infrastructures between people. You look at people, you look at objects, but we’re not taught to look at the relationships between people and objects, or between people and people. But dancers are. That’s really what making a piece is; it’s about relationships between people, and you’re taught to look at that and to identify these relationships.

Levi: All the time.

Jamm: All the time, and every system, every corporate organization is built on these interrelationships. Dance is so amazing in that. It’s almost as though you have some sort of “sixth eye,” that you can see these things … it’s a training that is not taught in our contemporary Western educational system.

Levi: In rehearsal, it’s really easy to immediately sense what other people are going through. It’s hard to ignore the presence, because everyone is communicating on this energetic [level], for lack of a better word.

Jamm: It’s true, and that is what is so amazing about dance.

Levi: I’ve had this conversation with many people lately about social dance, about dancing for fun and how much fun that is, and how much we all either still do—or have—loved it. Most dancers I know don’t do it that often, and, in New York, all the clubs closed down. (or most of them) But, that’s why (many of us) we were into it in the first place, its the feelings that you get from social dancing. It’s not so much what happens in a theater. You perform sometimes and you’re having this intense physical experience and the person in the audience three feet away from you is asleep—it’s this insane divide. I feel like AUNTS takes the “artistic-experimental” dance and recontextualizes it in a place that is social, that starts to feel like that again.

Jamm: We experimented with the social aspect of dancing in all of our spring shows, starting with the panel that we did at Movement Research. In terms of trying to do what we wanted, that was the first time we had a DJ there. The DJ was playing throughout the entire panel, which was set up in a completely different way than any panel that I had ever seen. The DJ was playing with the volumes, and then there was a performance that happened when we pushed all of the chairs away once the panel discussion was over, and then it turned into a dance party.

Levi: What was the panel?

Jamm: For the MR Festival 2005: Open Source. They asked us to do a panel on the future of dance. That was after all the Fall Bashes and we had an idea of what we were doing. We looked at some panels a nd there was one at DTW that was absolutely horrendous. Fluorescent lighting, some tables up in the front, and these two women moderators. It was two hours and by the time something got going, it was over; and the moderators kept interrupting with their questions. Sarah was on that panel, I think it was something like “the absurd in dance.”

So, for our panel we interviewed all of our panelists beforehand, extensively—sometimes for three hours—to get them started thinking about the idea for the panel, which was their grandiose vision for dance in the future. I recently looked up the word “grandiose,” and it is something that is delusional. So, it sounds good, it’s flashy and extravagant, but the actual implication of the word is something that is characterized by exaggeration.

We wanted people to think in the biggest way possible. What did they want the future of dance to be? Whatever it was—really, really think about what it could be. We asked people what they thought their responsibility was and a whole set of other things. The panelists were picked on the theme “Grandma takes the kids to the Opera;” i.e., people that were younger and not so caught up in the drama, like parents are, and grandparents who are like, ‘yeah, fuck it!’ and treat the grandkids to ice cream and go to the opera.

It was great. Douglas Dunn, and Phyllis Lamhut, and Janet Panetta, Luciana [Achugar]…….among many others. We had them all sit around in a circle, we gave them a bunch of wine. Rebecca and I moderated it in a very specific way, more as hosts at the actual panel. We had done so much work beforehand because we didn’t want the conversation to be interrupted, so it was this four-hour conversation. It was self-moderated, almost, because the panelists kept on coming back to this grandiose vision themselves…it was really great! Miguel came—we didn’t invite him because we felt like he was too much of a parent—but he came to the panel and brought his grandiose vision statement with him. [laughter]

Levi: He crashed the panel!

Jamm: And then, after, Douglas asked, ‘Why don’t you do more jumps?’ and Phyllis was like, ‘Why don’t you all go home and do your dance in your communities and get it going there?’ (because she grew up in New York) And everyone was like, “NOOOO!” and it was so great! And DD [Dorvillier] was yelling at [Michael] Portnoy…it was all this crazy shit…. [laughter].

We had a circle of panelists and there were performances around the periphery. And, sometimes performances would trickle in, but mostly just around the periphery—you could watch them, or not, and sometimes they were more distracting or not—and Julie Atlas Muz and Ede Thurrell, they were the coat check girls with the microphones and they were kind of the peanut gallery who could make comments whenever they wanted to…[laughter]

Levi: Where was this at?

Jamm: It was at Chashama. It was the last event for the MR Open Source festival, right before Christmas…there was a lot going on… …but, anyway, with the DJ, it turned into a dance party and it was really great, that after all the build up, people just did social dancing. So, then we really got into social dancing and all of the [AUNTS] late shows had social dancing at the end.

Levi: Would people dance?

Jamm: YEAH! That was when the idea for the next AUNTS shows came into play. We had this dance team with different dance captains each time, a band, and the whole thing was Conan O’Brien-, Pina Bausch- and SNL-inspired.

The first two were at Panetta Movement Center, which ended up being a big disaster for Janet, because there were too many people and it went late, which was supposed to be ok, but turned out not to be. We also realized that it was in a studio and people had to take their shoes off, and it was too much of a typical “modern dance show,” even though we tried hard to break it up, it didn’t quite work out. So we changed the last show to CANADA Gallery—which was a great show – at the end of the show, everyone was dancing!

Levi: I have two more questions. I’m thinking about the modern garage movement; I don’t want to go into it too much, but I was really enamored by the idea of it. It felt like this series of performances that not that many people are going to see [laughter], and what intrigued me about it was this idea of experimental dance as associated with urban centers, particularly New York. The idea of taking a road trip and stopping in people’s garages to do experimental dance seemed to me like a great decentralizer. And also, this idea of not being afraid, not having this “us” and “them” attitude about the sophisticated urbanite versus the American suburbanite. So, those are two takes on it, but I would love to describe what it was.

Jamm: This is separate from AUNTS.

Levi: I know. It’s some of the same people, but even more people.

Jamm: The moment that I really started thinking about what AUNTS could be (it didn’t have a name at that time) was when I was in San Francisco that summer. I was both on break and in the middle a dance I was making and I had done the trial run and was not happy with it. I had some friends in San Francisco, but I didn’t even know why I was there; what was I doing? So, I decided that I would make a dance in this garage—my stepfather’s garage. I thought the garage to be a really a perfect setting for dance. This was a really small, one-car garage, the driveway inclined up, a perfect place for everyone to sit. I thought the garage was so similar to a theater but so much cooler. Like, when we’d be rehearsing in the garage and people would be walking by and [thinking] and asking us ‘what are you doing?!’ So I made a dance with two of my friends, basically, so I could hang out with them all the time, and then another one with my little sister and her boyfriend.

I wanted to have other people show work, too, but it didn’t quite happen. We did two weekends of these garage shows, and they were really fun to do! I think that people just had no idea about what was going on, but I felt like everyone had been in a garage before, and everyone knew what it felt like—people don’t know what it’s like to be on stage, but people knows what it’s like to be in a garage. But, then the garage transforms into something else.

It was also another rock band reference—a garage band—practicing in a garage. Doing dance wherever. After, I thought, “Oh! Let’s do a tour! Let’s travel around the West Coast…” So, I got the family car, packed it in tight and contacted people I directly knew or friends of friends or sometimes, like in Santa Fe, it was my mom’s friend’s friends. That ended up where they couldn’t be there and there was a housesitter, but they said, ‘it’s fine, you can still do the performance.’ I’d never even met them.

I’d also been reading this book called Graceland, and there was chapter where this guy joins a traveling theater to get away from somebody who’s trying to kill him. In every city and town they would go around with their trucks and everything [yelling] ‘we’re performing tonight, we’re performing tonight!’ get everyone riled up and then they get together and perform—and I thought, ‘Ok, that’s a pretty awesome model.’ So then I thought, ‘how can we actually make this happen?’

If I had done it a different way, I could have sent out press releases to local newspapers, but that takes a lot of time, and was not my main focus. In Portland, there was a girl that did that for us and we got a lot of press, and people came, but those were not some of our best shows. As our tour progressed, we realized that part of the work in making this happen was that we had these posters, and when we got to a town or city we would put up the posters, talk to people and invite people. Our audience was people that were friends of people in the house, friends that we had that were there, and then the people that we riled up around the town [laughter]. Every time it was really different, and it was really nice rehearsing in a garage. I was trying to think about dancing on concrete and hoped it would be okay on our bodies, so, together, we made this whole warm-up/maintenance that we called “dancing together” and we’d do that for an hour and half or two hours every day that we were rehearsing or performing. And we’d do it and be looking out on the hills, and lightning, and the crazy hip-hop ice-cream truck coming by, and the neighbors and other people.

That was partially the idea of looking at your resources and trying to think about what you could do with what you have and what is available to you.

Levi: So much of this conversation is all about context, the context of experiencing dance, and I just wonder about the content. It makes me think about new technology and delivery systems and that language, and how content becomes secondary to context.

Jamm: It’s true. With AUNTS, that was one of the reasons why we were trying to do Team One, was to focus more on content—to really focus on work and being able to talk about work and look at work and consider work. If you were part of the team, then you could propose as many people as you want, but you wouldn’t be able to show video or slides. You would have to talk about their work and why it would be a viable option for the consideration of Team One. We did feel like AUNTS was so much about context and situation, with the bashes and even with the grandiose vision, it was more structural, rather than the work that you are doing…and I’m still trying to figure that out. As the structure is forming, I’m trying to figure out how the work fits into the structure and how the structure influences the work. Which is one of the questions that is influencing the decision to have representatives, to really think about work. I tend to do more work influenced from the outside, but there is also a deep work that can come from the inside that I haven’t figured out how to promote. Yet. In the spring I’d like to do some kind of residency-type work that AUNTS sponsors.

Levi: It also has to do with how the artists themselves take up the situation.

Jamm: It’s true… I would love AUNTS to go in the direction of sponsorship. For instance, Michael Helland is doing a show at the Chocolate Factory and he’s at every single AUNTS show, and he’s helping write grants right now, and he’s really fantastic. I said, ‘let’s have AUNTS sponsor your show and you can use AUNTS and whatever it is, how you think of it, in whatever way you want. Not just in terms of a mailing list, but how you can use this thing and use it however you want. You could make our whole MySpace page about the Chocolate Factory [show], change these things that we have and utilize them for your own purposes.

That might be more about an individual’s work, but it’s also a little bit more about content. I’m hoping that there are some galleries or studios or homes that we can team up with, where there’s a long-term AUNTS [residency]; somebody gets to be there for two months or something, and basically we give them space where they can do whatever they want, but they have the time to work.

In the long term, if AUNTS does get money, how should that be divvied up? Right now, money goes to rent space. We have to rent the Event Center, so we have money going towards that from somewhere. When we did the Movement Research panel, they said they could give every panelist $25 and we said, ‘don’t bother.’ So, if we don’t have that much money, the way I could deal with that would be to do some sort of space. It’s sort of inspired by P.S. 122, when they had that Open Movement— do you know about that? It was such a great thing; so many people met each other and got to do work in that space. Maybe we could have a space that we’d have it for Friday and Saturday for eight hours, anyone could come in and use it and make work; all together. I wouldn’t want it be about performance, but about work. A workspace that the only thing you have to negotiate would be the other people working in the space and what they are doing. Dancers are so good about that: when we have tech rehearsals with everyone in an hour and a half, it somehow works because everyone’s so used to dealing with space in dance that they just naturally can negotiate the space very well, and efficiently.

So that might be the next step. Because, if I am going to pay someone for a performance, I want to give them a shit-load of money, I don’t want to give them a pittance.

Levi: [pause] Yeah, it starts to feel like a gesture, rather than anything useful.

Jamm: Yeah.

Levi: Again, it goes back to a space where people can just work together and negotiate with each other—it’s about being together in community, in a way.

Jamm: I know, it is, it really is….

Levi: …no, not in a cheesy way, though! My last question is: what is your experience in the New York dance community so far? How do you feel about it?

Jamm: I’ve been here a few years now, maybe six years? I moved here when I was 21.

Levi: Me too. I’ve been here nine years.

Jamm: Ok…so…I LOVE dancers and people in the dance field. This is a field that am involved in and I am happy being involved with. [pause] I have had some exceptional opportunities to work very closely with people in ways that were unique, in terms of being an assistant to a few different choreographers, where I really got to watch the trajectory of them, their work, in the dance community, in the public sector. Not just Sarah, there was Karol Armitage which was a whole separate thing. And, I got to see how they were supported in this domain. I was a little bit appalled with Sarah and her lack of vision in terms of sustainability. I was completely awed by her brilliance in terms of choreography, performance, thinking about art, making art.

Since I’ve gotten here, especially after September 11th, and the international community dissipating, a bit (don’t worry, we have another bottle Levi), I’m mostly excited that it’s just this kind of level playing field in a way right now. There’s just nothing here, in a certain way. I try to get other people excited about it, because, with nothing there, then you can really do whatever you want—you don’t have any restrictions. As compared to Europe and you get these grants; there are people who play with the grant structure and write grants for one project when it’s almost done so they can get money for the next project. But, mostly, in that structure, dance is very institutionalized. So, I can be excited by the fact that it is, a little bit, dying out or that has totally died out in the United States. Because, there isn’t any real solid funding for making dance! So, recognizing that, because there’s no funding, you can just do whatever the fuck that you want! The only restriction that you have is monetary, and that doesn’t necessarily need to be so much of a restriction. You can ask for space—if you can look around for it, you can find it. But, in terms of making the work, you can make whatever you want, and you can build yourself up in whatever way you want right now.

So, I like the community here. I get a little bit annoyed when are dancers are sooo dancey in terms of only being interested in dance. I love the rigor of dance and doing dance all the time, but I think that it’s also important to go hear music and hang out with people that aren’t dancers and go to museums and have time to rest and do nothing, practice your observations that are based not only in making a dance.

Levi: Being a human being.

Jamm: It’s not just dancers that that’s happening to. Everyone in New York—the work ethic—it’s everywhere—Germany, they don’t have those four-week, lovely vacations, or in France. Everywhere the work hours are going up.

I kind of love and hate that Ann Liv (Young) doesn’t go to see dance shows. There’s this whole thing that you are obligated go see your friends dance, that you have to go see all these shows—but, if you don’t want to see them, leave! Why waste your time. Don’t be so passive. In dance training you’re taught to be submissive, but you don’t need to be that way.