Leslie Cuyjet: In short, I want to understand more about your work as a curator. With a background and experience in dance and visual art environments, I feel like you have this unique perspective when it comes to the marriage of art and performance. In addition, I know you as a friend, but also, I wanted to reflect on my experience being an artist you curated. When you and I worked together you took such care of my creative process. It wasn’t simply putting a show together, or making contacts, or pulling art pieces together to make a shape or gesture out of a theme. There was a lot of conversation involved. A lot of conceptualizing involved, and I realized I was unclear about what is involved in your work as you seem to operate on another level. So that was really the impetus to sit down with you because I want to know more about what you do.

Alexis Wilkinson: People have different ways of doing curatorial work which is sometimes working with existing artworks or a set thematic or gesture as you mentioned. I’m really interested in working deeply with artists, in having conversations that guide how I’m conceiving of an idea, or set of ideas.

LC: Right, with people.

AW: Yeah! With artists and dancers and performers and thinkers. Something that guides my work is my desire to think through an idea with artists and dancers. There are many ways to put together an exhibition, right? There’s by way of an idea, like: “I want to make a show about x,” and then you look to find artists and plug them in to that set concept or framework. For me, the way that exhibitions or projects come together is usually being in conversation with artists, or being compelled by a particular artwork, or a set of practices and using that as a guiding force, really letting myself learn from artists. From there, I start to put things in relation: what idea or object or movement practice or poem or whatever – is interesting in relation to that anchor. Then looking at how those new elements shift or expand the umbrella concept. It’s like a bottom up approach.

LC: I remember at SculptureCenter — is that where we first met?

Kim Brandt, The Volume, 2017. In Practice: Material Deviance, SculptureCenter, New York. Photo by Kyle Knodell

AW: Oh yeah!

LC: I remember one Kim Brandt rehearsal I was in, she announced that our next rehearsal a curator was coming for a studio visit. But working in dance, we rent the studios! So what does a visit to a rented studio where we happen to be having rehearsal mean? We ran through what she was working on for you and you two had a conversation after. Now thinking back on it, knowing you better, it was starting to make sense to me then, that you were having these conversations earlier, to hone in on what the show was or could be.

AW: Right. That show was called Material Deviance, and it was especially challenging in this amazing way, because it was an open call format where you have to select artists, and then determine the curatorial concept from the works that the selected artists were making specifically for this exhibition. But with that show, and everything I do, I selected the artists intuitively. I was thinking of course about the quality and rigor of the work, but of course the ideas and practices I feel personally invested in naturally shaped that selection of works. For Material Deviance, I was thinking through larger ideas of movement and circulation, that ranged from the incremental or bodily to the social and infrastructural. That’s a really good example of the ways in which dance in particular, can inform an exhibition. When I think about movement it has a lot to do with the body and dance practice, but that also ripples out to all these other modes of practice like sculpture for example, or registers of movement in everyday life, or how you move through a gallery space.

LC: That’s something that I should mention, that show combined sculptural, capital-V visual art pieces right next to live performance with bodies in the space. How those things came up together, and that’s interesting you say that the dance practices, not just the performance part, I’m not going to use “embodied…”

AW: (Laughter)

LC: But someone who’s present moving through a state and informed by the space and other things in the space, and how that can help you see other pieces in a different way.

AW: That’s always a goal for me.

LC: When you say your style, that’s what I think of. You blend those two things, in a seamless way, and I’ve never understood that before.

Alison Kuo, The New Joys of Gellies, 2019, Abrons Arts Center. Programmed in conjunction with Extremely absorbent and increasingly hollow, Cuchifritos Gallery + Project Space, New York. Photo by Georgette Maniatis

AW: I came to grad school training in a curatorial program from the position of having a background in dance. There, I was spending a lot of time thinking about the hierarchy in museum structures that positions visual arts at the top and dance at the bottom because of its elusiveness and that it deals with people. That positioning felt like it was being crystallized when dance was being brought in to museums in that moment around 2012 or 2014. I kept seeing this uncomfortable thing of dancers and choreographers being asked to “respond to a painting or a sculpture” which felt like that just reinforced that hierarchy. Or the tactic of situating dance in the atrium, or any interstitial space that wasn’t conducive to viewing the work. Or having performance as entertainment at an opening reception. At that time, I was also looking at the ways in which dance histories were being presented exhibitionarily; in modes of presentation that have video, photographs, or residue of a moving body on a wall or a space. There’s nothing wrong with these. But I was personally feeling really dissatisfied with a lot of those approaches, because it felt representational and I was interested in something more active. I wanted to work through what it would be to rearrange that hierarchy. Some of this comes from Jenn Joy’s book The Choreographic. There’s a part in her introduction when she inverts Carrie Lambert-Beatty’s question “What does it mean to say a dance is photographic,” (referring to Lambert-Beatty’s scholarship with reads of Yvonne Rainer’s work through a photographic lens) and asks instead “What do we mean by saying a photograph is choreographic?” The book prompts the question: what can we learn about an artwork by being with live performance? That question really guides how I work.

LC: I love this question. That’s what gets me so excited about your work. I was so eyeroll-y about seeing another performance in a gallery, smacked on top of someone else’s work, and it felt like a lot of labor for the performer for not a lot of reward. When you curated my work, Fossil in your exhibition A Collection of Slow Events in 2017, it felt like there was a real blending of all the pieces in the show that it was more of a collaboration. There are still questions like, what is a gallery space that functions both ways? Is it a “neutral” territory for both performers and art? If you’re doing a lot of jumping, you can’t do it on a concrete floor. So is it the wrong piece or the wrong space? What is a space that is nurturing and conducive for both? I don’t know what that answer is but I’m really glad there’s somebody thinking about where they coexist as equal partners, instead of this hierarchical, or even linear way; one before the other. That just feels really exciting about how not only they can work together. I’m always thinking this way as a maker: can I expand dance beyond the field? I don’t necessarily need to or want to, but I feel like for sustainability reasons, for gaining new audiences, which also ties into sustainability, for interesting collaborations for new ideas, and inspirations that that expansion is definitely in our futures. Politically, how do we get to be equal playing partners in an art world that sells paintings for millions of dollars and dancers make $20 per hour. How do we blur those lines between funding for performance and visual art? That’s kind of where my mind goes, that gets me excited.

AW: Totally! All of that. I also think, going back to this idea of equal footing, I think about what we can learn from performance by pulling it into more visual arts-oriented spaces. A performance audience has expectations of viewing time going into performance, versus the expectations of viewing time in a museum, I’m really interested in moving the way that you view performance to this other space, which has to do with duration, extended looking, and also, maybe not always, this quality of relation. What you do as an audience member matters in that performance space. You’re contributing some sort of energy, there’s a stronger sense of relationality.

LC: With another body in the space.

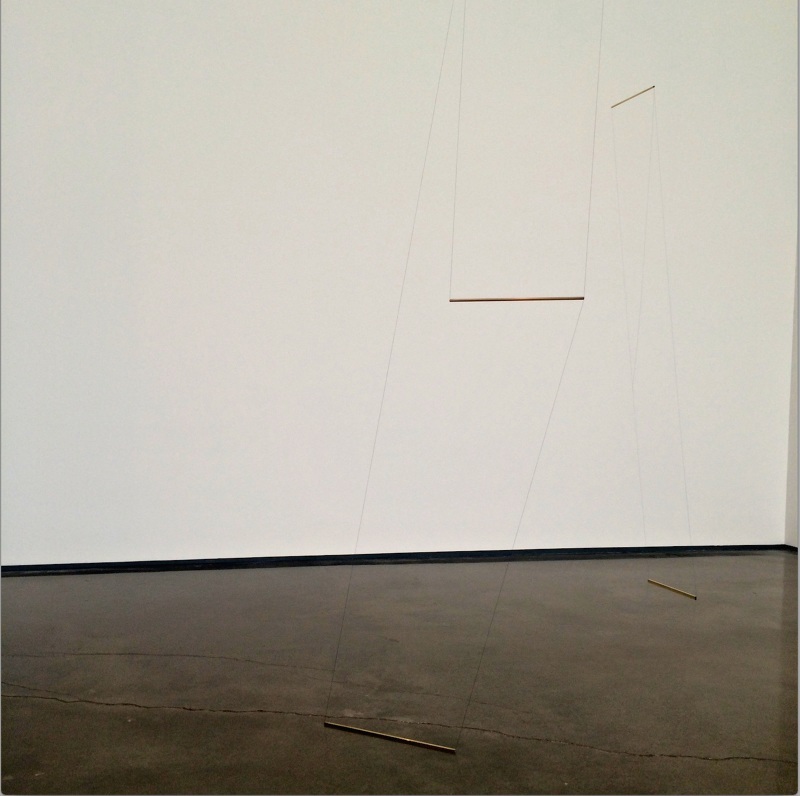

Jonah Groeneboer, Bent Hip, 2014; and Fractured Plane, 2015. objects are slow events, Hessel Museum of Art, Bard College, New York

AW: Yeah. I’ve also been thinking about the private-public mode of looking or attending to and thinking about how that plays out differently in encountering performance and artworks. This comes from a personal desire to slow down and have a long extended private emotional experience with an artwork the way you are conditioned to when attending a performance.

LC: That’s the thing I love about performance nowadays I see so clearly: I just made someone not look at their phone for an hour. How do you do that in a museum or gallery setting? When you’re talking about an empathetic exchange, while you’re sitting with something, there’s just a different energy exchange. You’re more vulnerable in stillness. Especially if something is slow and durational, you’re able to breathe and calm down, and I just think that’s nice when I get to experience as an audience member.

AW: Right, doesn’t everybody want to experience that?

LC: Why not! You have an appreciation for slow durational things. Making space for that to happen feels really important.

AW: It’s true, I do love slow durational things.

LC: When you curated Fossil, which originated as the last 8 minutes of a 30 minute dance, at first I thought that section was too long. It’s the longest “section” at the end of the show, people are going to get bored, or want to leave. This is my self-critic talking. You told me, I could just do that section for an hour. In the original piece I wanted to create an illusion as if it just kept going forever; out of the theater, out the door, down the hall, to the street. I wanted it to really traverse a long time but felt limited by the conventions of the theater and dance performance and a shared evening. And you said, “Um yeah, you should do that.” You gave me permission to take time. In a gallery it’s not here’s your ticket, here’s your program, come have a seat and watch this dance. It’s such a feminine thing to say, but it’s ingrained in me to consider how much space I’m taking up and consider how I move in the world. I felt comfortable for the first time to do this thing I wanted to do and it’s going be 45 minutes long, and people can come and go, and that’s ok.

Leslie Cuyjet, Fossil, 2017. A Collection of Slow Events, The Luminary Gallery, St. Louis. Photo by Brea McAnally

AW: Two things. One, I think all performances, people should be able to come and go always. People have different levels of ability to sit down and be in a space for a really long time, and I take issue with being held captive in a performance setting. Like when seating is situated so that you have to cross the stage, for example. If we’re talking about accessibility, these factors make performance inaccessible. Even if it’s a proscenium setting, open that space up. You need to stand up, go to the restroom or stretch or whatever, do it. I’m interested in that mode of contextualizing a space as a generous mode of being with, but that’s also – going back to what you were saying on the allowance of doing that kind of thing – what’s also at stake with working in a slow durational way, there’s such a demand for spectacle.

LC: You mentioned entertainment earlier.

AW: Exactly, that sort of demand or desire for entertainment or spectacle that choreographers and performance-makers have been working past for years that gets reinscribed when you bring performance into a visual art space. There’s so much to learn from looking at something over a really long period of time, or paying close attention to things that appear one way but are actually in some state of change. There is so much in little details or rhythms. It feels imperative to spend the time to be with those things and observe change over time. That leads into the types of artwork I’m interested in. Not only am I interested in that quality in performance and dance when it’s situated in exhibitions. I’m also interested in art objects that operate along those lines, that have qualities of change over time. Minuscule, often hard to see, elements of movement and change.

LC: This artist, Jonathan Schipper does this: microscopic movements. The first piece I saw of his, I didn’t know he was a New York artist at first, because it was in my hometown in Louisville. It’s outside in front of this pizza place that was converted from an old garage. It’s called The Slow Inevitable Death of American Muscle, or something. There are these two muscle cars facing each other on a track that slowly pulls them together and like an inch or a fraction of an inch a day. So sometimes you’re there and it looks static or other times you’re eating pizza and suddenly hear a pop when the car finally starts to bend. In the end, they are smashed up against each other like a car crash. I was obsessed with the slowness there. Like, how dare you! It’s like a reward when you check back in, but you also have to go away. It’s an investment coming back to you, which is something that performance doesn’t do. With a dance performance, it’s a weekend one night. I see it once, and that’s it.

AW: Well, the temporal registers are really different. So what you’re doing in an hour or weekend is extended for this car, is stretched out over the course of year or however long. They relate, just on different temporal registers. What’s at stake for me in bringing dance, performance, and visual art close together, is thinking about change and the fact that everything is always in a state of change. To hold on to the idea that anything is static feels dangerous, in a larger social-political sense. For me, one of the most valuable things about performance is that it happens and it’s a given that everybody has a different experience of it. Everybody has a different vantage point in the audience, everyone was in a different mood, everyone leaves with a different memory of what they experienced which is what we are truly left with of live performance in the end. That’s true for artworks too, but there’s an idea that it’s the same; that because an artwork is not visibly moving or changing that there’s one objective truth to a work.

LC: It’s that moment in time and a desire to catch it. In that example of the cars, there is a constant action of the hydraulic system or whatever pulling the cars together. But only a select few are there for when that dramatic change happens. Let’s say a dancer was engaged in the same phrase of movement and that was the constant, as a dance audience member would I have that same delight through witnessing the changes of constant effort over long periods of time? I’ve always questioned form and the way you’re talking about engaging with performance, if we challenged audience members about how they consume performance, I think they would rise to the occasion. That’s all I’m saying, I feel like there’s space. My body changes every week, by the season, or time of day, and that changes how I watch for sure.

AW: What do you mean challenged by, like open up a different, continuing performance in a different setting?

LC: Yeah, the theater convention. There’s something about the reflex of walking into the theater at 8 o’clock, that triggers a mode we operate in. As opposed to a space that doesn’t have seating, or there’s no discernible front, then those cues are telling you that you can come and go or you can move around or you can sit on the floor, you can have agency on how you want to engage with the piece. So what are the other tick marks in the range between those two modes? It’s a spectrum, and somewhere in that spectrum is this blending of performance and visual art.

AW: I think, again this thing of slow durational pieces feels closely aligned with meditation because there’s this perception that nothing’s happening, but my favorite moment is when you think nothing’s happening, or you think you’ve found a singular pattern or something that you sort of come to, and realize something completely different has happened. I’m thinking of Kim Brant’s work, specifically in this example. It gives you an allowance to let your mind wander a little bit and then come back to something that has changed while you were…

LC: Zoned out.

AW: Away. Yeah!

LC: I meant away. (Laughter)

Lauren Bakst & Yuri Masnyj, Temporary Walls, 2017, In Practice: Material Deviance, SculptureCenter, New York. Photo by Kyle Knodell

AW: I’m also thinking about style and approach. I continue to return to or orient myself with this idea of care. That’s something I learn every time I’ve worked with dancers, in any context, but very specifically visual arts spaces. The ways in which different practices and modes of care are required to think about bodies in these spaces, as opposed to art objects. Specifically working with dancers and the type of care that needs to happen for bodies to be OK, safe and taken care of. This also extends to art works in this interesting way. There have been a lot of instances where I show artworks that look vulnerable. Like those works made of threads [by Jonah Groeneboer] that I included at the Luminary [Gallery, St. Louis], people constantly tried to blow on them or agitate them somehow. I guess they were trying to test the limit of this extremely delicate and precarious material that was taking up a lot of space? There’s something interesting and quite disturbing about how people respond to vulnerability with object like that. But I know it happens when people are performing on the ground in these contexts, the audience doesn’t know what to do or how to act appropriately for a number of reasons. That’s always a learning experience that I keep at the forefront of my mind. Also, I’m interested in making shows where there’s an element of maintenance; for objects and bodies as care.

LC: When you mentioned that thread piece, there was so much in that show that was precarious, the Simone Forti piece and those stools, and the thread piece, and us: six performers moving on the floor. That required attention in care, for sure. I was terrified that we were gonna bump into that or destroy this.

AW: It’s never the dancer that fucks anything up. (Laughter)

LC: You’re right, it’s not really the performers, but I wonder if other people felt that tension. and what else can you do but sit still and go with it.

AW: I hope other people felt that tension! While I don’t want people coming in and trying to mess with vulnerable artworks or people, all of the precarious seeming artworks that you mentioned were included to propose a more conscious viewing experience, to give visitors an opportunity to really tune in to the space and the objects around them. Maybe this is a lofty desire, but how can you take what you’ve learned from these contexts, in terms of respecting vulnerable objects or people in a position of vulnerability and take those lessons into life, to the people and spaces you’re interacting with in the world?