IDEAS

Anat Ben-David : I’ve got this idea. What do you think about the idea?

Andrew Morrish : Well, I need to make it clear that I’m talking about a particular approach to a particular art form. It’s not ideas in general, it’s ideas in relationship to improvisational performance. I first started to improvise when I was 31, so I had 31 years of ideas to work with. For a few years I had always started with an idea and I thought “this improvising is easy… I’ll just start with an idea”. And then one beautiful day I couldn’t think of an idea. I think that verb is really interesting…I couldn’t think of an idea. I was a bit ashamed of myself as I had been using ideas but I had never given any thought to where they came from. I had been treating them like they were a fundamental unit. As if nothing smaller than an idea existed. Much like the physicists thinking about fundamental particles in the last century. For a long time atoms were assumed to be the smallest unit possible. Gradually the possibility of smaller units was speculated, and then they were finding totally mystical units inside the suddenly big and clumsy atom.

I had to think about where do ideas come from? Are there more fundamental units within the structure of “an idea’? Because I worked with young children a lot in the eighties I knew that we are not born thinking. When we are born we are just a bundle of sensation noticing devices. I decided that the fundamental units I am working with are sensations and what happens is my body receives information from the outside world, this gets fed into my brain and the brain says I can turn that into an “idea”.

In a general sense an idea or concept is also a way of “knowing” what something is, this “knowledge” means I don’t need to attend to it anymore. As the brain matures it can begin to manipulate the ideas inside the brain. The brain begins to believe that the WHOLE process happens in the brain. The truth is that it all happens because of the stimulation of the brain through sensation.

ABD: This is Andrew Morrish by the way, I realize we did not do an introduction, we just went into the flow. Andrew, what kind of improvisation can become an art practice?

AM: My premise for my performing is that I don’t have a plan for the content before I perform. I don’t want to be coy about this, there’s lots of things I do know i.e. when it’s going to be or where it’s going to be. I usually think about what I’m going to wear, and a decision has been made about how long it will be. Sometimes I have given it a title, which is an indulgence, I just give it a title because it’s fun, I don’t allow the title to consciously influence what I do in anyway. If you accept my initial premise, then it’s interesting to ask, what kind of art can you expect? This question helps me stay in, and trust, the improvisational process. There are lots of more modified positions in relationship to prior knowledge of the content and I know I take a fairly purist position.

One of the implications of this decision is that the content is emerging while the audience is watching me. As a result I know there is something happening between me and the audience, and I am being shaped and formed by them. This doesn’t mean I ask them for ideas, it’s not that kind of improvisation. In the tradition of theatre improv often the audience is asked to provide starting points in some form. In my form it’s not that direct but I believe that in the interaction there’s a lot of exchange of information. Indeed, just the fact that they are watching, changes me.

COLLABORATION

STUDENT : Would you say that this is collaborative?

AM: Yes, in that way it is a duet. It’s collaborative and it’s ephemeral. I am trying to make some- thing that works in this moment between me and this audience. It’s very specific.

ABD: And the skill involved in improvising is something that one would then hone down, and later decide what the output will be.

AM: I think every art form has an implicit virtuosity. And behind the implicit virtuosity you will find the traditional values embedded. Of course we live in a time when many artists want to question or interrogate these embedded values of distinct art forms. But I would say that in improvisation the implicit virtuosity is working with your attention.

ABD: And there is skill involved?

AM: Yes, there is in every virtuosity.

ABD: You can become a really good improviser?

AM: Yes, you can become really good improviser.

ABD: I think if you do something for long time, you are good at it.

AM: Yes.

NOTICING

AM: Implicit in improvisation is working with one’s attention i.e. noticing what you notice, then having the skill of shaping and forming from that attention is the next cycle. Another cycle is the structuring of the material over a period of time. My current preferred length is 50 to 55 minute solos. I feel this both gives me time to structure the material and to allow the structure of the material to emerge.

ABD: While you’re doing it ?

AM: Yes, while you’re doing it. No material is pre-planned or cued. I experience it as an unfold- ing. That gets much more complicated if you have another person working with you or if you have a lot of technical things set up in the space. In addition, having pre-set technical elements can possibly mean that you begin to accidentally slip into the “written” or « set forms”. I think that could also be great but the fact is, I want my art to be about the shaping and the forming and the decisions I make, whilst the audience is watching. The decisions I make therefore reveal me as an artist. So it’s suddenly very simple.

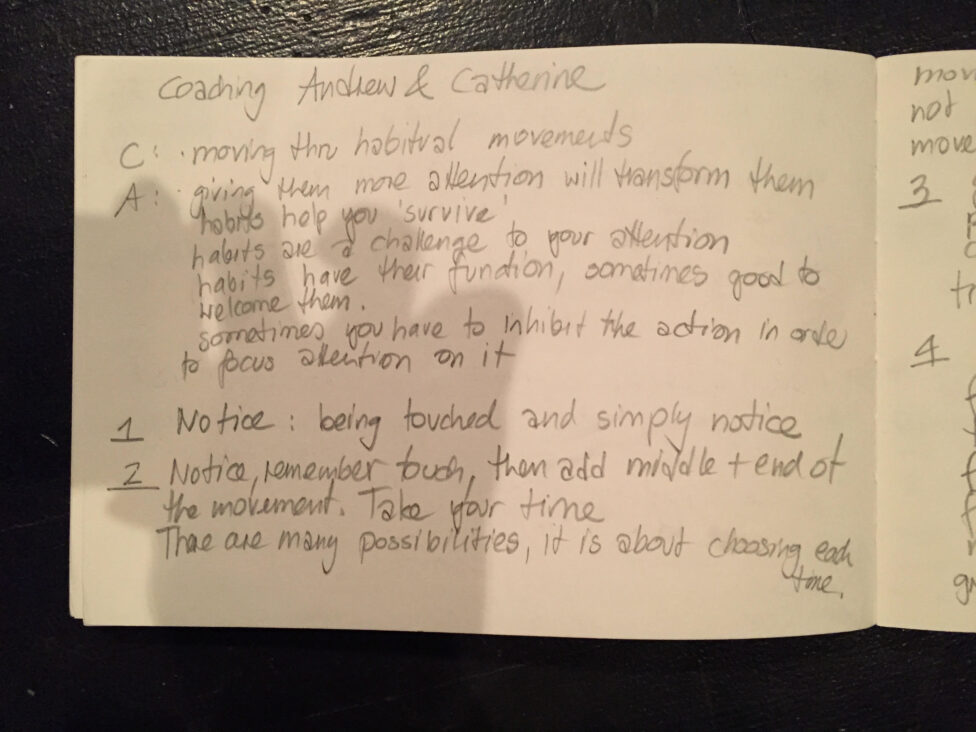

Notes On A Masterclass Session Between Andrew Morrish And Catharine Cary, Theatre De Bouxwiller, Alsace France, 2016

USING SPEECH

ABD: I am being selfish now and I want to ask about speech in improvisation.

AM: Yes, please ask me about speech in improvisation. I’d love that.

ABD: I find that speech in improvisation is perhaps the hardest thing to do and to watch. As we tend to be structured in the way we speak, maybe that’s why words sound estranged in the process of improvisation. Catharine and I had a discussion after a session, about how speech arrives. (Catharine is very good at it.)

AM: Yes, she is.

ABD: Catharine said that her speech is almost involuntary. I’m so jealous. I want it to just come out like that — detached from consciousness. We have spoken about Tourette’s Syndrome and having no control over our production of language; we also spoke about Oliver Sacks’s book « the man who mistook his wife for a hat ». So how do you do it so that the speech is not composed ?

AM: I also love that an improvisation will not be what you wanted it to be. It feels like the improvisation is a little bit rebellious sometimes.

ABD: When you improvise, do you think: “I’m going to say this thing” or do the words just come out?

AM: Both ways. If I know what I’m going to say then the interesting thing becomes « When am I going to say it and how am I going to say it ? » And the other important thing is « Will I keep listening to myself when I speak? » Normally when I speak I don’t listen; my brain is on autopilot. When I am performing I am listening, so the gaps that appear in my speaking can become interesting for me. In other frameworks these gaps might be called mistakes, but in improvisation, they are gifts. I once said the word, I was just talking and I said, “it’s very excremental.” Immediately my brain knew it was a new word that means “things get shittier in smaller and smaller steps”. This really exciting but it’s also a “mistake”. In another framework, e.g. acting, if the script says « incremental » then « excremental » is wrong and you have to fix this mistake. In improvisation you say “wow” as you know that your brain has expanded in that moment. I also think that excremental is a word that we need right now. I think we live in excremental times. (laughter).

In this process, by noticing/listening to yourself then spaces start to open out as you break down the hegemony of unquestioned units of meaning.

Student: So that improvisation works as an interruption within the ordinary use of the word ?

AM: YES YES YES , I would definitely say that a huge skill base within improvisation tools is interuption. By learning things such as making decisions in places where you would not normally make them. The definition I am using in my teaching for speaking poetically is: “don’t speak normally”! Once you interfere with what “normal” speech is for you it immediately becomes more poetic. If I just go a little bit slower, that’s more poetic. Or I can go faster, I can speak high- er, I can speak lower, I can leave a gap, put in a new word that I wasn’t expecting, I can change the palette of words that I’m using. Use words to paint a picture in someone’s imagination, choose words that paint pictures rather than those that make you think about what I am saying. All these kind of things are connected to interrupting your own decision-making.

Student: But still be a catalyst for more information, because you are kind of talking about words as sort of a brush stroke or gifts ?

LANGUAGE

AM: Language is definitely about meaning. But it’s also possible to give yourself permission to be surprised by what you say. Why accept that the thought you had five seconds ago is the one you want to « talk » to the audience about ? At the same time I don’t think the kind of perform- ing I do is about giving people information, it’s about a shared experience. It’s about the an- thropology of why theatre exists. I have a low-level theory about how theatre started. Most of my theories are low -level. A low- level theory does not have much evidence to support it, it is just something I have made up to make my work more plausible.

I imagine that theatre, and performance was created with a lot of cold frightened people sitting around a fire. Animals were making noises in the dark, Then, someone from the group says, « Do you remember when…” It began as an act of community to give people enough courage to get through the night. That’s what theatre is about for me. It’s about that shared moment and then somebody chooses to step out of the group and say something which somehow the group can be with that says the sun will come up tomorrow.

In the end, I think that it’s about my ability to break down my material into smaller and smaller units. The sensations are remarkable and potent units of the body.

PLEASURE

ABD: You have talked about pleasure in the work.

AM: I usually speak about pleasure and ask my students to talk about what they enjoy as a means of processing their experiences in my workshop. I could also say “interest”. We could rather talk about what is interesting. But I think that this word implies thinking is required. Asking them to talk about a pleasure is implicitly asking them to describe a sensation.

ABD: You should do a course about pleasure.

AM: Yes, great idea. Pleasure in a sensation. When you put chocolate in your mouth, you do not say “ what an interesting concept”. No, when you put chocolate in your mouth and you say “MMMM.. .“ that’s what a pleasure is.

STUDENT : What kinds of things are detrimental to improvisation or what state of mind should you be in ?

AM: I believe that for all art forms it is really helpful to have a clear idea of the paradigm you’re in. Sometimes I see people who think they are improvising but they have a whole heap of other paradigms at the same time. Of course this is fine, hybridity is very interesting and necessary. But I think it is good to be clear about what paradigm you are in. This will always help you to evaluate what happens.

That’s how you can know if excremental is a “mistake” or a “gem”.

This article was first published in the Royal College of Art Research Journal, PROVA, in June 2018.

Impromptus au Jardin/Singulier(S)Pluriel 2019, Constantin Leu and Catharine Cary, photo by Fabien Collini