Amy Khoshbin: We were asked to do this conversation by Tess Dworman and I think it might have been sparked by my recent work. I am a performing artist and so is Carlos Soto. After the election, as an Iranian-American I was inspired to return to my activist roots. I’ve been doing a lot of direct action, performance, and installation work in response to xenophobia and the current administration. There’s so much to say about that. And another thing that’s happening with the current administration is talk about defunding the NEA. Before we get to talk about that, a conversation that I’ve had a lot and I’ve had with Carlos in the past too, is about this idea of labor and financial support in the art world, as working artists.I guess my first question is to Carlos and I’ll answer it as well…what has been our experience with the work that’s gone into projects in terms of labor, creative energy, collaborators etc., and how has that been supported or not been supported by institutions around us? So let’s start there.

Carlos Soto: Actually you start.

AK: You want me to start?

CS: Yeah.

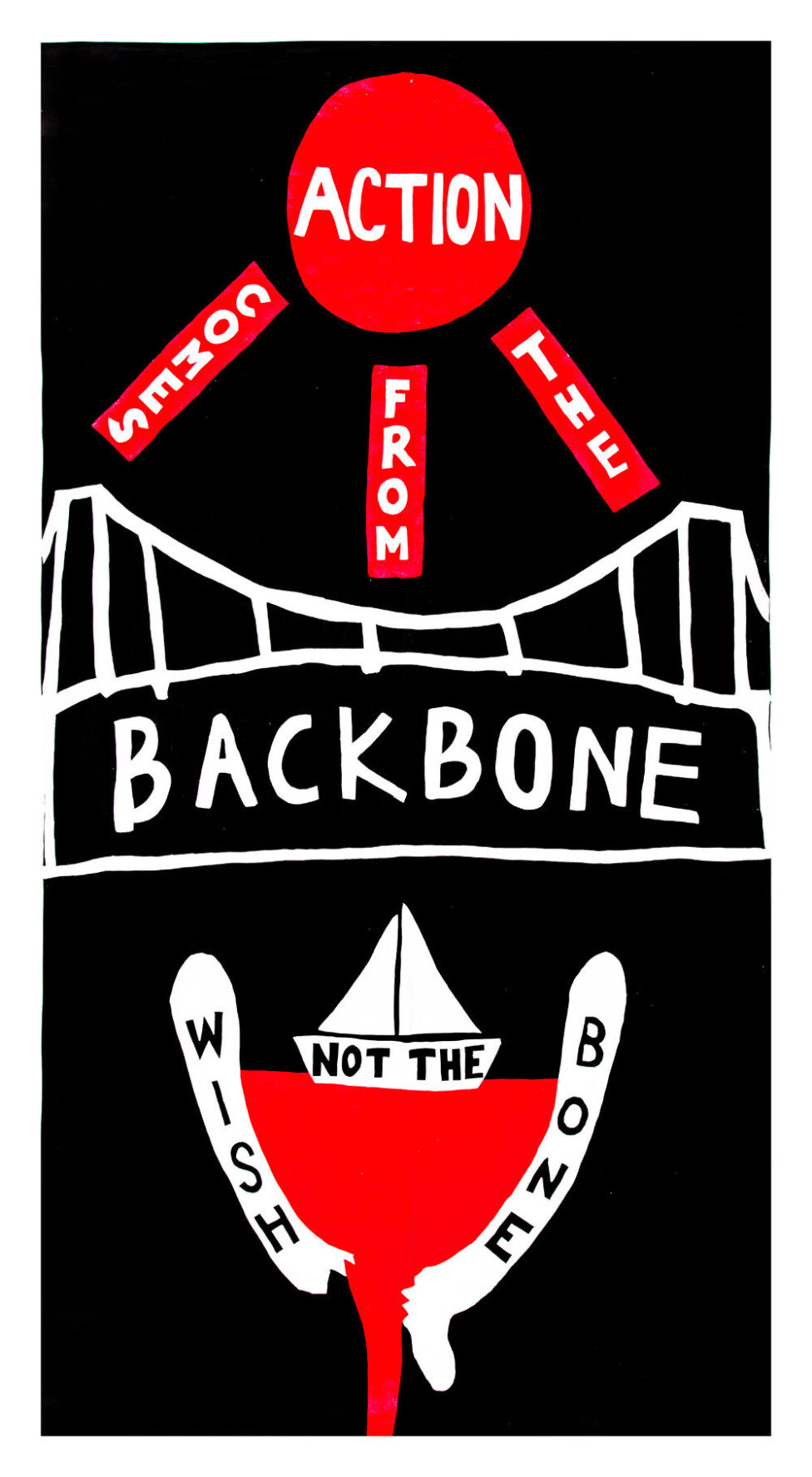

AK: OK so I’ll start. So I got really activated after the election and I started on this project that is called “Word on the Street”. I invited Anne Carson who is a poet that I know and love to respond to the current political situation with language and poetry. She wrote a few phrases, and I realized those as large-scale, hand-crafted felt banners. These banners are used out in the streets in protests and have also been shown at institutions. The whole idea of this project is creating this breakdown of the invisible barrier between the institution and the street. So this project is very politically oriented and because the street is part of the equation, it’s harder to get funded, but we do have a partner now which is Times Square Alliance. It’s going to be opening around Labor Day in Times Square, so that’s really exciting. And it’s great because I’m working with my siblings’ art production company House of Trees on it, and we’ve gotten Carrie Mae Weems and Wangechi Mutu to create original banners for the fall. We’re going to have all of the banners photographed and printed on vinyl bid banners, which are the ones that you see on lamp posts, so we’ll sort of subvert the advertising paradigm with language of resistance. We were lucky to get some funding to continue on with that.

Image created by Amy Khoshbin + Anne Carson for “Word on the Street”

AK: The second political project I’ve been working on since the election is running for local office. It came out of that initial investigation. Protesting in the streets was excitingly working on some level, some small level, specifically around the Muslim Ban when we went protesting at JFK and in conjunction with the ACLU were able to temporarily overturn it. I think as the current administration has gone on, protests are still happening, but the energy is waning and I think we’re seeing a real need to actually engage in the political environment in a more direct and maybe institutionalized way. We can’t ignore the institutions that are in place. I don’t think that we’re going to see a bloody revolution any time soon, so one question is – can we work within institutions that exist? I started to think about this idea of running for office and how I could get involved on a local level. I feel like so many people want to get involved and they have no idea how to engage. So then I thought, well maybe I’ll run for City Council and I’ll use my ignorance about local politics as a prompt to actually start an investigation into this process of running for office and documenting that process for others who might be interested. So I started down that road. Well, the problem with that is you need a staff, and to have a staff you really need to pay these people, and to pay these people you need to have financial support, and to have financial support you need an institution, a partner, a corporate donor, a commission, or some such thing to be able to proceed. That’s the problem that I’m running up against, and I think a lot of other artists that are making political work or not— that’s why I wanted to talk to Carlos because I don’t think his work is directly political in the same way. You know?

CS: Completely unpolitical in that sense I guess, by comparison.

AK: Right, I mean you’re political in your own ways.

CS: My work has no position one way or the other, that I’m aware of. It’s more formalist.

AK: Yeah, which is completely valuable and interesting and I love your work. That’s why I wanted to talk to you. I think to only talk about work that is political—yes it is harder to fund political work always and that’s been an obstacle across the board throughout history—but I think there is this preconceived notion that maybe young artists or people that aren’t involved in the art world have where they think that because you’re an artist, you’re somehow mysteriously able to support that art one way or another.

CS: Yeah, there’s this kind of invisible capital that artists apparently have that we’re able to just produce things.

AK: Exactly. Maybe you can talk a little bit about that. For me, it’s been a problem. I’ve had to postpone this project. I think it’s for the best. I don’t know enough about city council and civic engagement to really have a true run and know that I would succeed. I need these four years to gain information and to do the research to actually win in 2021. However, I also feel like a big stumbling block for me and for a lot of other artists, political or not, is a question of how we get our work funded on a short term or long term scale, and what are these ideas of capital?

CS: Also, where do you get taught to do that? Nobody ever schooled me, clearly, because I’m not figuring out the financial—

AK: [laughing] I know!

CS: Nobody’s trying to help either, in a way.

AK: Yes.

CS: Like I was saying before, there’s no project-specific guidance. That’s not something you’re born with. It’s not an instinct.

AK: …and honestly art school, theater, performing arts, dance, etc., all of these, at least for me in both undergrad and grad school, that’s not necessarily a part of the conversation either.

CS: Yeah. Sometimes art isn’t even a conversation in art school. I have a friend that studied fashion in Antwerp and he doesn’t know how to make anything. They just talk about theory. There’s no practical application of what you’re studying. In terms of contemporary art practice, especially in performance practice where it really is something that requires a great many people and a lot of funding, because it’s completely immaterial, you’re dealing with a staff. It’s a supporting army of people to get this stupid thing done.

AK: Yes, we’re not stupid. [laughs] That’s a different conversation. Self worth.

CS: Every show is stupid. Let’s put it that way.

[laughter]

If it’s not stupid, it’s taking itself way too seriously.

AK: True, agreed.

CS: But those things just aren’t taught. So either you’re naturally good at spending your parents’ money or dating the right person or courting rich people. I’ve done none of those and frankly just have this kind of allergy to sucking up to people with money. This friend of mine said “You just need to know 20 rich people and write them letters and you’ll get some funding.”

AK: I’ve heard that.

CS: I just don’t want to— I can either spend time making my work or sucking up to people with money, which is a full time job on its own.

AK: Right and that’s the thing people don’t realize. If you’re in the throes of making the work, especially with performing arts work where you do have a staff, you’re a Producer.

CS: …and you have a kind of long gestation period, but at the same time the gestation period is to generate the work. Generating the work is part of it, producing it. But when you’re left in this desert of the world and expected to figure it out yourself, I can tell you exactly what I need and when I need it but somebody’s got to take control of that.

AK: Right. I know, and trying to get that funding, first of all that takes a ton of time—

CS: It takes a ton of time!

AK: And it taps your resources in a way that doesn’t feel great, to be honest.

CS: Right, because you’re just writing begging letters!

AK: I had the same problem where I was working with an institution, they wanted my piece to happen, and there wasn’t enough money that they could give. I had to do a Kickstarter to raise the rest of the money because it was a huge group of people working with me on it. I think we are both the same in that we want to pay our people, as best we can, what they are owed.

CS: I don’t want to work for free, and I don’t expect people, even if they’re friends of mine to do that. I don’t want to call in favors. I don’t want to ask people to do something that I wouldn’t do.

AK: Exactly. I feel like the activist part of me kicks in and I want to raise this community up. I don’t want to drag it down. I don’t want us to be all having to work for free.

CS: It shouldn’t become a system of making work by cashing in every favor you can. If that’s the model, we need to figure out another structure.

AK: If we cash in every favor we can, then we can’t keep making work consistently. We can’t have any momentum. We can do that one project and then we have to wait for the well to be filled up again with all the labor we have to do for free to be able to do the next project. That’s just not sustainable and that’s not how we work. We were just having this conversation where someone asked us, oh what’s ISCP? Well, it’s a place where you have to pay to go for residency and because of that, people from outside of the country end up going to that residency.

CS: Right, because if you’re French and you’re accepted, you can always go to the French Ministry of Culture and get a grant to fly here, stay in one of their cute apartments and do your shit.

AK: And that’s not going to happen in the US. It’s exactly as you said, we have to count on those 20 rich people, but again—

CS: Rich people love it. They’re never offended when you ask them for money because that just means you’re acknowledging the fact that they have money but then they’re like, oh here’s $500, good luck, tell us when it happens. Those relationships are really hard to build and they’re taxing and it’s kind of a waste of time. It’s gambling.

AK: It’s gambling.

CS: Just like doing a Kickstarter or doing a fundraising campaign. If you don’t raise it, it’s coming out of your pocket. I am not emotionally, financially independent in the way that I can just shovel out—

AK: I like your phrase too, emotionally…

CS: …$15,000 out of pocket just because oh I need some lights, or I need this. And it’s not like those are superfluous things. They’re not like follies that I’m just trying to dress something up with. Part of creating work is thinking about what your idealized version is, and then throwing all that shit away because it’s a fantasy and you could never afford it, and just getting down to the point where you’re comfortable with what it is. It’s still for the most part the work that you set out to make. Then below that, if you take more of it away and then it becomes something else, and then it’s not really the work you’re setting out to do and maybe that’s fine for you, but for a lot of us it’s not.

Carlos Soto’s Have Mercy on Me (2010), The Watermill Center – photo by Lovis Dengler Ostenrik

AK: That’s another piece of the puzzle too, that people don’t realize especially with performing arts work. The work is shaped either by funding or a lack of funding that’s received. In projects of mine, that’s pretty much how it’s had to go. Oh I had all these amazing ideas in a way—

CS: Yeah the means guide the form in a way.

AK: The means guide the form. And we’re very resourceful in that way. I think that’s how we’re resilient and how we create the work. But I think there’s this issue where we’re the content producers, we’re the content, in some ways we’re the heart, we’re the backbone of the art world right? We’re making the material, we’re the meat of the meal. But then…

CS: But the meal gets monetized.

AK: The meal get’s monetized, and we don’t—we’re like the cows that are in the meatpacking industry.

CS: Right, they’re sucking our tits.

AK: Yeah, they’re sucking our tits or they’re putting us in a little pen, and then leading us out to slaughter we don’t really see any of that capital for our next project. We don’t. We’re barely breaking even, if that.

CS: Especially when you have a commission which also includes your fee and everything you have to spend and at the end you’ve spent another $10,000 of your money if you have it.

AK: And who has it?

CS: And you walk away with nothing. You spend years working on this thing.

AK: Yes.

CS: And what do you see for it? Except for a bunch of emails from friends who are like sorry I couldn’t make it!

AK: [laughter] This is our jaded selves right now because ok, if you think about the positives, anything about this trajectory of the emerging artist, it is a gamble. You’re investing in the sense that you’re showing in a certain place and you’re showing for nothing, because you want to put that place on your resume, you want to gain those contacts, you want to gain that exposure, you want to gain that worksample that gets you to the next thing and then that thing is hopefully a little bit bigger, a little more exposure, now you’re getting press, hopefully, fingers crossed. Then maybe you’re finally getting a little cash to do the production, and then the next one, maybe you’re getting a little cash in advance of the production, and so on and so forth.

CS: Then your production value grows and you’re willing to spend more time developing or fine tuning it because you’re not worried about getting your teeth done or getting your metro card or whatever.

AK: I thought that that arrow, or that arc, was a forward and upward arrow.

CS: Mhhmm. It’s very horizontal.

AK: [laughter] Yeah, it’s horizontal and you see little bumps and huge dips and a bigger bump and a bigger dip and it sort of keeps doing this back and forth, up and down ad nauseam. I’m at another place where I’ve had a boom and I’ve had a dip and now I’m regrouping after just closing this festival. I was lucky enough to curate the Movement Research Festival this year that Carlos was a part of, which was so great. It was an incredible amount of work and it was an incredible experience and I met so many amazing people. Now I’m regrouping in my life and I’m looking at what’s next and I’m like wow, I really have to make some cash and extremely quickly because I’m in a place where I can’t pay my rent. So that’s sort of the question, and that’s maybe the next little bit we could talk about. Maybe we don’t have any solutions for this. But, what could be some potential solutions? I want to get a little utopian because I think that’s where we have to start in the same way that we have to start with our creative projects. And then we have to sort of pull back from that. I don’t want to live in the art world ghetto anymore. I want to ask for what we deserve and I want to try and get it to the best of our abilities. When people agree to work for free and have employed interns working for free, that creates a really problematic dynamic, especially if you think about it in terms of class and race. If you think about the kids who are starting out, the kids who are able to live in New York City and work for free at internships, they are usually coming from privileged position where their parents are paying for their life and they’re not usually people of color who are struggling to survive. I don’t want to put it in racial terms because that creates really fucked dynamics from the beginning. It’s really about class. But it does create this problematic dichotomy from moment one where people are working for free because they can and the people that can’t aren’t given those opportunities to even enter into the world to then be lifted up, in theory. I feel like there should be, and I’ve been thinking about this a lot, a union, but I know unions are problematic for a lot of reasons.

CS: Yeah well, especially in theater where unions stand in the way of you actually getting stuff done.

AK: Exactly. Not to degrade them because in theory they’re amazing organizational tools for people, protections.

CS: Because god knows every director is going to try and abuse a stage hand.

AK: You know? But then the stagehands are just sitting around, you know, and we’ve all experienced that.

CS: Well they’re like sitting there checking their phones doing nothing, so.

AK: [laughter] So it’s sort of like how do we balance this out? Maybe unionize is the wrong word because it rings the wrong tone in people’s ears. How can we somehow organize and agree to not work for free?

CS: Well it also assigns the work a certain value. When you work for free, it makes the work valueless. You’re not placing any value on it by working for free. So what worth does it have?

AK: Exactly, if you’re not going to value it yourself then how is anyone else going to value it?

CS: “And if you can’t love yourself how the hell are you going to love somebody else?”

Amy Khoshbin in the Van Alen Institute Arteries Festival, photo by Melissa Levin

AK: I was looking into artists’ unions and I saw there was an artists’ worker union called the Artists’ Union in the 1930s in New York during the Great Depression and the WPA (Works Progress Administration) era. They actually got some shit done.

CS: Were they considered communists?

AK: By some. Of course. But they had some street actions and some demonstrations and they got some forward movement on getting people paid and labor rights issues. When the Federal Art Project of the WPA was set up in 1935, the good conditions offered to artists, including the relatively high pay rate, were largely a consequence of pressure by the Union.

CS: There’s this really funny film from the 20s in France titled, “Le Million” and it’s about this group of artists living in this cold water building and they all owe the landlady tons of rent, and someone’s going up the stairs and she asks what they do and he says, “Oh, I’m an artist,” and she says, “ No you’re a thief, a scoundrel, and you’re a criminal.” I think there’s a problem where artists look too much like freeloaders because nobody understands what artists do, and so they don’t put any value on…it’s not like you’re making tires.

AK: Right.

CS: There’s a very qualitative and quantitative evidence of what you’re doing. You start off with a chunk of rubber and you end up with a tire that goes on a car and people drive around with them. Artistic output is really difficult to quantify.

AK: Someone just recently was saying to me that art comes from privilege on some level, and the product is a product of privilege and so people look at it as such. I would argue that that is not true. If you look back at cave paintings, these are the origins of language and communication. It’s art.

CS: Certain works of art in non-western cultures are produced for a ceremonial purpose and its value is in its success ceremonially. They were originally not meant for trade. Eventually they were meant for trade. But those are different times. It’s also one of the curses of Western art, which is much more about concept, where it has no purpose, it fills no purpose. And if it fills a purpose, it’s not considered art.

AK: Right, I think the real problem that we’re in right now is a societal conception that “Art” with a capital “A” doesn’t serve a purpose, when the reality is that art is the origin of design, is the origin of a lot of the media and technology that we’re seeing today.

CS: …and its value is dictated by some really mysterious things that even I don’t understand. But also, in terms of non-western art, there’s this argument that the works that were collected in the 20’s and 30’s, their value is dictated by a bunch of artists. Picasso, Nolde looked at Oceanic and African art and said this is what’s good and this is what’s not good. Then you have this host of dealers that are selling that to them and going back to Ghana or to the Ivory Coast and saying this is what we need and having the artisans produce these types of works…

AK: …or these “products”

CS: And it makes this kind of canon of what African art is, but there is no canon, that’s just a thing dictated by some white guy in Paris selling shit for 1,000 times more than he traded it for and taking it completely out of context. They become decorative works.

AK: Right, not knowing the context, the historical value.

CS: Also moving them out of the context where you’ll never be able to identify what these things are. Because you know, it’s just decorative art.

AK: Right, it becomes a totem to your wealth in some ways. It’s confusing because I think the valuation of art is so elusive, to all of us, to artists…

CS: Well was it Tino Sehgal who figured out objects, or even a concept is sellable because someone will be willing to pay for it, and as soon as someone is willing to pay for it, it has value?

AK: Tino Sehgal is especially interesting because I actually sat in on a meeting when I was working at the Guggenheim where one of his works was being acquired and that’s the only time I’ve ever sat in on a performative work being acquired by a major institution, and it was so interesting what was evaluated. What was of value to them was a set of instructions so it could be recreated. When you think about an archive and you think about the “societal value” or the value of these artworks, the fact that they are going to be recreated is of value to society, and so that becomes part of the package–the instruction set, its restaging, and the ephemera. The ephemera has to be of a certain quality level, so to even get the ephemera to a certain quality level, for some people that’s documentation, for other people that’s drawing, you know it depends on what your practice is.

CS: How do you mark things? How do you document?

AK: These are good things to think about for performing artists who are trying to finance their practice, and are looking to these institutions that are not coming up with the money they need… and of course it’s all a house of cards.

CS: Well, institutions don’t have any money because the government doesn’t give them any money. And nobody’s given money for it anyway. Except Aggie Gund.

AK: I know thank you, Aggie Gund! That was an amazing move. I hope more collectors do that.

CS: I saw a Ray Johnson exhibition in Chelsea recently and there’s this great little collage, that’s one of his “Nothings”. It’s one of his little black bunny and there’s a text that reads, “PLEASE GIVE TO AGNES GUND – nothing”

AK: [laughter] Because that’s what you actually need, maybe. For those of you that don’t know, she is a major collector and she, is she on the board at MoMA?

CS: She is President Emerita and Chair of the International Council and PS1.

AK: Right, she’s the president. She just sold…

CS: A Lichtenstein.

AK: Yes, a Roy Lichtenstein called “Masterpiece”. A painting that has one of the highest values– $165 million. What’s amazing about what she did is that She used most of that money to start an art for justice and criminal defense fund to try and work towards stopping mass incarceration.

CS: Yeah and to also challenge other collectors to put their money and their art where their mouth is.

AK: Everyone wants to get politically active. Well guess what, you’re sitting on the wealth of the art world and that could support so many, not only political projects but other art projects and other community engaged initiatives.

CS: If you’re sitting on a Paul Thek, and now it’s worth millions of dollars, maybe sell that…

AK: And maybe put that work towards artists with AIDS, you know what I mean? Visual AIDS and other organizations that need funding.

CS: Think also of the amount of art that people buy that’s sitting in a warehouse, that they don’t even have in their house because there’s an extra sofa. That’s how people collect.

AK: Oh my god, absolutely.

CS: Someone tells them what to buy and they think, “That would look really great above my Jean Prouvé.”

AK: Yes. And then the Jean Prouvé moves and then the other piece…

CS: No, they sell it at Sotheby’s because it’s not chic anymore.

AK: Yeah because it’s not on trend. I mean that’s a whole other issue and conversation. Art markets in the visual art world, especially now since there are prospectors, like the real estate market almost. Some of these works are being traded among hedge fund managers who are trying to drive the prices up among their cronies.

CS: …and it even feeds the whole publication industry of catalogs because catalogs for the most part exist to pump the value of something. You know a gallery will publish a catalog of some useless thing because they need to sell it and now it automatically has a publication credit.

AK: …and good for the publication issue but again, let’s look back at the artist. What is the artist getting out of the equation? Not much. If they are represented by a gallery, they get a certain percentage of that work when it’s originally sold and as it’s resold they see none of that. And often there’s that sad thing, like with Paul Thek, people die and then the work goes up in value because it’s limited edition.

CS: Or work gets destroyed. There’s a Paul Thek in Robert Wilson’s collection that was sitting in a warehouse for decades. Someone was clearing out the storage facility and opens this crate and there’s a little prehistoric diorama with playdough dinosaur, a landscape with little volcanos; the whole interior of the crate is painted. It’s so beautiful. When it’s closed, it’s just a nondescript crate that states “This Side Up.”

AK: Which by the way is amazing if you’re ever at the Watermill Center take a look, if it’s still up. It was up for a while when I was there on residency, October in 2015.

CS: I think it’s permanently up…We’ve circled and I’m sure we haven’t gotten to a point.

AK: No this is great. I think to distill what we’ve said, I think that artists should come together and start having this conversation more actively, about how can we support one another to raise up the community so that we’re not working for nothing. I am a proponent of community engaged activism within the arts community. Ears shut off when they hear the word “activism”. They need to get with the program, in my opinion. We have to have this conversation. Can we develop something like the Artists Union in 1930? Can we develop some kind of coalition, union etc. that actually has some legs? We are the heart of the art world. Without us, there isn’t an art world.

CS: …which is actually just the culture industry.

AK: Yes!

CS: I don’t even think about it as art. It’s just an industry.

AK: Yes, it’s a culture industry. We’re cultural producers. How do we monetize that? Don’t be afraid to monetize your work.

CS: …and don’t be afraid to discuss money.

AK: Yes. Ask for it upfront.

CS: …and don’t be afraid to ask colleagues and friends and peers how they do things. I think one problem is that kind of fog over what artists do and how artists make money. Artists have the same problems. We have blinders to what other people are doing and so we’ll naively go about doing things because we just think oh you know, somehow it happens. Somehow people are paying rent. A lot of that knowledge is also capital.

AK: Yes.

CS: How much do you get paid for that thing? How much does so-and-so get paid for that thing? How did they make that thing?

AK: Yes. Breaking open the process, talking about this openly. Being unafraid. Being unafraid to be vulnerable about it. It makes a lot of people feel vulnerable to talk about how much they’re making or not making.

CS: For example, I didn’t study theater, I studied fine arts. I’m coming into theater having worked in theater but I didn’t study it. So I’m just learning as I go along. I’m learning to adapt.

AK: Can you say a bit about what you do and what you’re working on as of late?

CS: I guess the catch-all is I’m a theater maker and designer and I’m sort of lucky I’m able to work in lots of different departments. I mainly work in theater, performing arts, and dance.

AK: You’re an incredible costume designer. That’s theater but you have a special skill.

CS: And along the way, I try and make my own work. It’s kind of difficult to balance because of course you get gigs and the gigs pay and often really well and it’s still theater in a way, so I’m happy—

AK: You’re still a part of a team in creating a work. You’re still collaborating on some level.

CS: Exactly. It’s not like you’re in an office somewhere, clicking keys kind of hating your life. It’s still within the same spirit.

…and where was I? …I make performances. You know, carving out time and space with bodies and light and color and sound and trying to figure out a new theatrical vocabulary that just doesn’t focus on a text or a narrative. I guess it’s nothing new but I feel like everything always ends up being some giant history lesson or something.

Nosferatu On the Beach, 2018, performance. Photo Credit: Tess Altman

AK: Well for me, for my job, I work in the arts. I do video design and installation and I work with different artists and institutions. I do short videos and it’s a hustle. I work freelance as you do. It’s feast or famine.

CS: Videography and editing and graphic design.

AK: We’re like hire us bitches! You know you do it all. You wear many hats. That fucking sucks but it’s just true.

CS: But it’s also great because some people don’t know how to do shit, and then they don’t know how to communicate, can’t explain what they want or what they need and in a way that’s part of my wearing that hat. Part of being an autodidact is that I want to learn. I want to be able to communicate to people what I want them to do. Most of the time other people end up having the same issue. When you work with people that have no idea what to tell you and just assume that you’re psychic and just don’t have the words to explain things…

AK: You have to be a good communicator. I’m similar. I’m a performing artist. I use movement, comedy, video… I do visual arts as well, collage, drawing and painting, etc. But it’s a real struggle. Over the last years, I’ve been trying to shift my practice to be able to work on my art a lot and get paid for it, while working money jobs when I can. . We’re actually at Lower Manhattan Cultural Council (LMCC) on the Workspace residency and we have to go in a minute because we’re having our last meeting…but you know institutions like this have been great because they try to encourage you to give yourself the time and the focus.

CS: It’s also nice that LMCC requires you to show up.

AK: They require you to show up every Monday. They require you to engage with the community.

CS: …and actually go to your studio and work.

AK: Totally. It’s taken me a while to shift so now I feel like I primarily do my artwork and I gig to supplement that. But the problem is there’s not enough funding from the artwork to support myself fully. I’m coming up against this thing where I’m like, oh my god, is there a way out of this constant work 60 hours a week hustle? I don’t know if there is.

CS: …and knowing and acknowledging your value. Like how much is your time worth?

AK: Yeah exactly.

CS: Because a lot of the work we’re doing is full time work.

AK: It’s full time work and I want to reiterate what Carlos said. People aren’t being trained. There are a couple of places you can look to for that help – Creative Capital and LMCC do some workshops for free that you can apply to as first steps in learning about time management and budgeting and all that. But I really do think it’s about valuing yourself and keeping this conversation open and really asking for what you deserve and advocating for that, because we do deserve to be paid.

CS: Because the worst you can say is “no” and the best you can say is “no”.

AK: Exactly, and to be able to walk away. I know for a lot of us this is hard.

CS: Know your limits and just know how much you’re willing to lose, or how much you’re able to gain. Letting go of stuff really isn’t failure.

AK: Exactly.

CS: It’s just acknowledging sometimes that you’re just too old for bullshit.

AK: Yeah or you might even be younger and you’re like no, I can’t take that 5 month long opportunity where I’m getting paid $5 an hour even though I can put it on my resume.

CS: Or exposure.

AK: Exposure only goes so far. Anyway, thank you Carlos.

CS: You want exposure, get an Instagram account.

AK: Yeah exactly. There’s so many other ways to get exposure now too, through social media. Alright thank you, bye forever.

CS: Do we sound like brats [laughs]?