Amelia Bande: We read together at Abrons, for the Belladonna launch of our chapbooks. You sat in front of the microphone with your texts, but you didn’t read. You spoke.

Constance DeJong: Yeah.

AB: I know that you’ve been doing that for a long time. So, what are the differences between writing something, reading it from the page, and speaking it?

CDJ: Well, huge differences and some of them have changed over time. I felt that it took me a long time to write something that I would call mine and worthy of pushing it into the world, and that was Modern Love. And before the book was finished I set about trying to find ways to be in the public. And there was this one thing that writers did at the time, and they were called readings. So I went to The Kitchen with Kathy Acker and we asked and they accepted us as a double bill. The Kitchen hadn’t had much writing before, it was mostly music and dance and video. And you know what a reading is, it’s almost a genre. The writer comes out, they read. So I was getting ready in my kitchen, rehearsing by reading the text, and I noticed I wasn’t looking at the pages anymore. And it was that thing, the minor epiphany, the flash of light. If I spoke from memory… Let me borrow your paper. If I take the paper away, the audience and I are in the same space architecturally and in the same time which is real time. And by speaking the text rather than reading it, the text is being constructed and coming into being in real time. That was a little epiphany. The paper came to mean looking down. Take it away and that was a performance in the moment. To me that was a big difference. And you know, it was just some stupid brain function that I could do, and so I pursued it. I’d always been really aware of rhythm, time, velocity, syntax, in my written language and even sonic qualities. And whatever that is, the ghost in the language, by speaking it again I was able to embody the language rather than read it. By speaking I was able to embody those things. Those changes of rhythm, and it wasn’t acting, because I was never really interested in representing the language in some acting way. So anyways, for my very first reading I had this little window in, and I‘ve been doing it since 1979 and there have been times when the performances are utterly simple, I sit down on a stool with a bit of lighting and a microphone and it’s an hour and a half later. Sorry, long answer.

AB: No, wonderful. When you speak about timing, it makes me think of Relatives. In Relatives you are interacting with a quote unquote co-actor that’s the TV set, right? The TV screen. So what was your relationship to time and speech in that interaction?

CDJ: Well Tony and I wouldn’t say we invented this duet, but it seemed like an invented form for us. When you first start collaborating with someone it’s like, well, what the hell is the form? We already knew it was performance, but having this idea about the duet with the co-actor was important. And then, from there we thought really carefully about the sections. That in my relation to my inanimate co-actor, the video, I would have multiple relationships to the screen and what was on the screen. I come out, I stand in front of it, I interact with it, what I say coincides with what is happening on the screen. I say “she and her baby” and I point and there’s she and her baby. So, the critical thing was for it not to be conceptual. And Tony and I found the material for each scene and then devised the relationship between the scene, the language and the video. It was very on the top of the mind to make each one of those its own relationship and its own composition if you will.

AB: From each of the fictional McCloud family members.

CDJ: The sections. Exactly. The first, the great grandmother is in the painting and then there are those weather map things that break that. They are a way to transition from one place to another as we march through. There’s a deviation because that’s the way we put it together, Tony and I. Being fiends of narrative makes you a fiend of breaking the narrative.

AB: Totally.

CDJ: So the whole section about the family crest, which is just some oddball in the family who went nuts with the subculture shit. And that pops in and out of that structure that’s marching from the past to….

AB: You don’t want each section to be…

CDJ: Yeah chronologies drive me insane. I think I promised myself when I was twelve to never write one *laughs*. So Tony and I, even though neither of us had ever constructed a work like this, we found common ideas that were also very lively, vital. We had a lot of shared interests in terms of what is narrative. Neither the text nor the images are freestanding. It was very important to us that the narrative be this third thing. The narrative is in the space shared by the spoken text and the moment to moment video on the screen and neither one is the driver and neither of them stand alone. People have asked me if they could publish the text and I don’t think so.

AB: Yeah, that’s really interesting. I don’t know if you care to talk about this, but the night I went to see Relatives, the TV screen failed. The video was constantly cutting. I had never seen Relatives before and for me at first, and a lot of the people thought the same thing, that this was the way it was. It was later on for me that it became clear that something wasn’t right. In the kung fu scene and then Tony approached and…

CDJ: And people heard me say there’s a demon in that television.

AB: And so it was a particular experience that night for the audience and of course I imagine for you. The performance ended and the first thing you said was “I need a martini”. So what happens when this co-actor falters and what happened to you that night?

CDJ: I think one advantage that I had was that I’ve become an experienced performer. And that served me because it was an utterly catastrophic thing that happened, not a little thing like a light flickers, it was catastrophic. I kept looking up at the booth because I’m working with the sound guy. I keep looking up at the booth like “Somebody help me here, what is going on? Stop the show. Save me. Get on the mic and say we’re having technical difficulties and stop the show.” They’re up there and suddenly they realize it’s the monitor. The performer doesn’t know any of this. So at some point, I mean the brain is kind of interesting. I have to be extremely focused onstage anybody with an hour’s worth of cues and language in their head, you know, you’re kind of full up. It’s really interesting that there’s time for these lightning thoughts to come in. So first I thought someone was going to save me and at some moment my brain says to me “You’re not being saved” *laughs* and I’m like “Ok. I am going to wrestle this puppy to the ground. I’m taking this thing all the way.” And I just went for it. And it involved a wee bit of occasional improvising. There was enough visual information left when the screen would come on that I could readjust to where I was. Am I on the mark? Am I off the mark? Do I have to speed up? Do I have to slow down? And that was a lot of work to do moment to moment to moment to moment. A soon as there was an image on the screen I would side-eye it to check: Are we together?

AB: Yeah, wow. So you’re still working with your actor.

CDJ: So I was still working with an actor yeah *laughs*

AB: I mean it’s almost as if the actor was more alive than ever.

CDJ: In its dying.

AB: In its dying!

CDJ: Well you know I have to say I didn’t have any time onstage to think this way, but numbers of people within the next day told me that they thought it added this layer of meaning that’s about technology and the human. But many people saw that and “The failure! We know we’re going to be screwed by the failure of technology!” You know that whole conversation about our lives now so intimately linked to technology. We’re bionic. These devices are extensions of us and that dependency came to mind to people in the audience, and what happens when that fails, when that relationship ruptures and breaks. Many people came to add that understanding out of that moment of catastrophe which I thought was interesting.

AB: Then I read somewhere that people had seen this like the battle between the human and technology, or the performance and technology.

CDJ: Narrative and technology also.

AB: Exactly and you said “In 1988 Tony Oursler and I did not approach Relatives as a battle, narrative versus technology or technology versus narrative…”

CDJ: No absolutely not, and I pointedly, and so does Tony, use the word “duet”. And everyone has to remember that we were not screen dependent yet. We didn’t have these phones, a computer was a big luggy thing. If you even had one it lived in a studio room or somewhere, they were big. This moment to moment relationship, nearly bionic relationship we have now wasn’t then, it just didn’t exist. So a duet means two things, to contribute and participate to make the composition. So that was on our minds. The other thing that was on our mind was an iconic image, because the home appliance that ruled the world was the television, and the person and the TV, and the person and the TV, that kind of iconic image, and then at the time it was very novel to end with it being a computer screen, with one of the characters, a woman, being a gamer, writing games.

AB: And maybe people would think it was strange that a woman was a gamer?

CDJ: Yeah, women do a lot in Relatives. And it also made sense. I didn’t know anybody, I didn’t model that off of anyone. But one knew it was going to be a battle. Would the tech industry allow us in? I think it made a lot of sense. And those were games of that era. The video games. And the final image is a fractal, and the fractal, again, at that moment was kind of the most up-to-date visual information image that existed. The fractal was a new idea of “there’s no end to measuring, there’s always a smaller and smaller space between the atoms and in between the space and between the atoms there’s another space.” So fractals end the piece as at that moment in ‘88 being the most up-to-date technology.

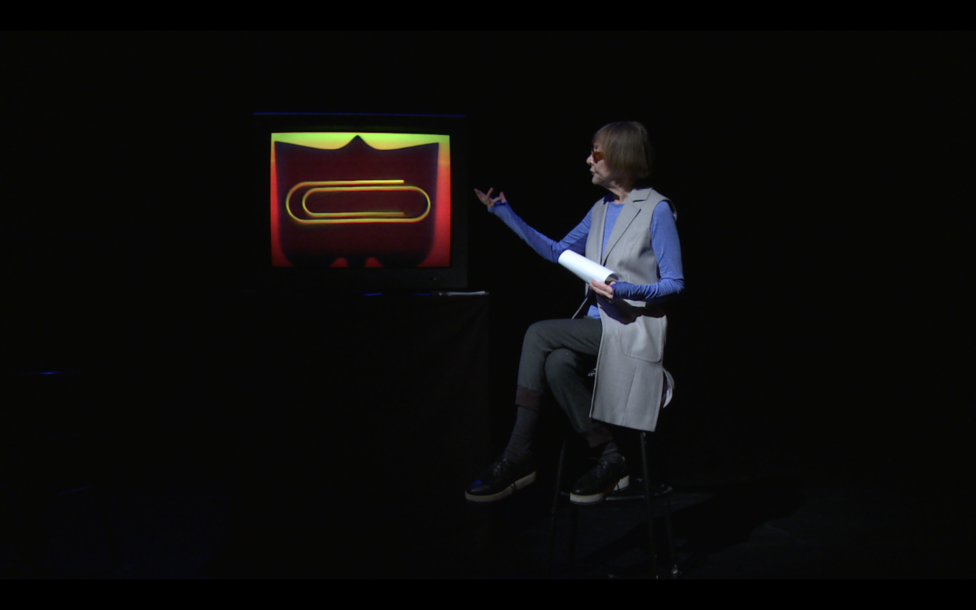

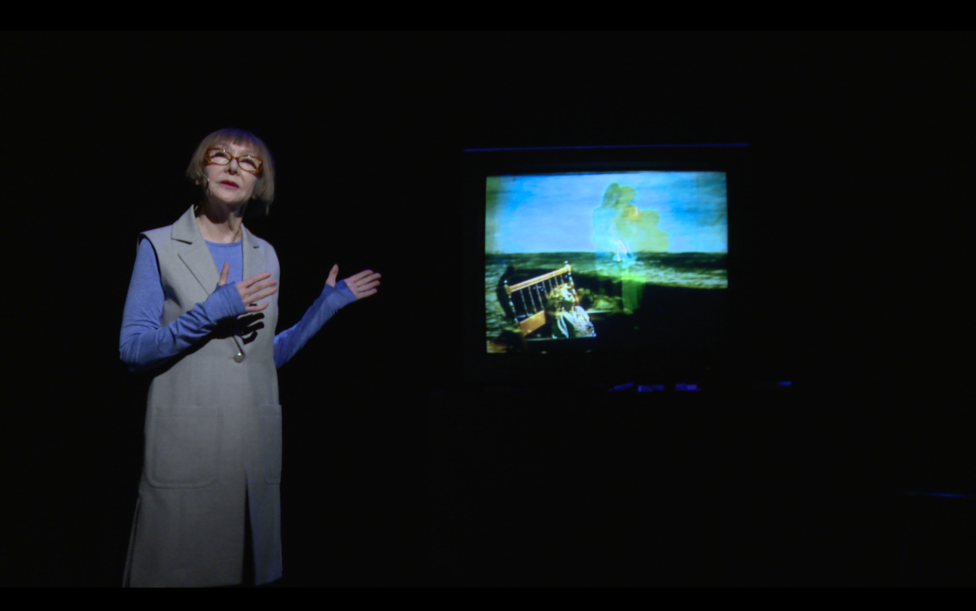

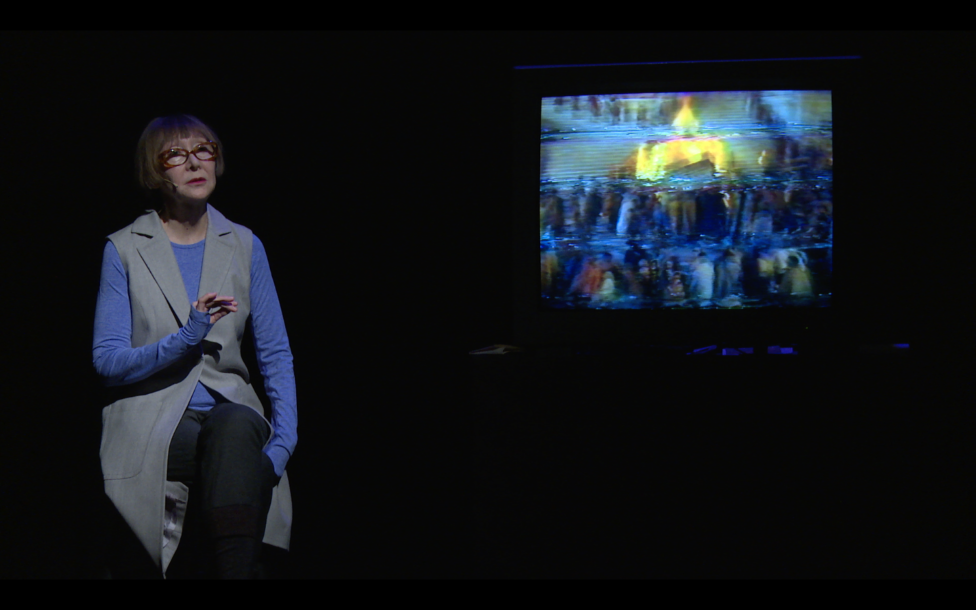

Constance DeJong in Relatives. Photo courtesy of The Kitchen.

AB: That’s crazy. In Relatives, you have a family.

CDJ: Yeah, yeah, it’s a family saga.

AB: It’s a family saga, but it’s not quite a family drama. It’s not about the relationship between the members. There’s not a “is this family functional, dysfunctional?” But I was also thinking about how at that time and even before that, the TV was this thing that…

CDJ: Family family family!

AB: What was the role of the idea of the family when you and Tony made this?

CDJ: Oh wow, I’m sorry if this gets long because there’s a number of answers. One answer is Tony and I both recognized and were interested in the generational evolution and/or development of technology. People are born into a moment with technology. It’s an existing structure, you can look at that. W each have it. And by the time you’ve lived a while you belong to several of those generations. So, in a formal sense I didn’t only borrow from one family saga, we borrowed from that notion. You know, the technology during the Civil War introduced telegraphy. And quickly telegraphy is like a damn miracle, you’re receiving a message from someone who’s not there, that’s a miracle in that time. So, it’s the Civil War, everyone has at least one person dead. It was the most violent battle the country had ever experienced and almost all the families in the east coast lost people, so they’re in mourning and desperation. And within a very short period of time something was invented called the spiritual telegraph. The idea of telegraphy, that you’re not there, but you’re sending me a message became “you’re not there and you’re actually dead and I’m getting a message from you.” So those kind of coordinates between what’s in the moment and what’s the technology in the moment and how do they come together was at work as well as this fictional family. Short answer, I’m not a representational writer. And the thing that people call a story doesn’t interest me. The “so called” story. And it never has and I’m utterly consumed by what narrative can be and do, but that thing about story isn’t an interest of mine. I was aware of it and I thought somebody’s going to point that out to me that these people never have dinner together or something. So I took this thing that I really can’t stand, which is the family saga, the genre which is always so clunk clunk, next, next. I borrowed it, we borrowed structurally it as a chronology and had this other idea of generational connections to technology. Miraculously, one person in every generation of one family, it’s absurd.

AB: Of course, there’s a lot of humor in it.

CDJ: Yeah, it’s an absurdity.

AB: But it also takes you away of this type of addiction to what the family drama is going to offer.

CDJ: Yeah, we need another one of those…

AB: Exactly.

CDJ: I don’t think so.

AB: The next question is a question about the collaboration. Did you write the text? Did you both write it? How was the process of working together?

CDJ: It can’t be separated, it really can’t. It was a two-person endeavor in terms of both the language and the visuals. And it would be impossible, it’s not necessary. It’s impossible and not necessary to pry it apart. We were always working together on it.

AB: Yeah, I somehow thought maybe Constance wrote the text and Tony made all the images.

CDJ: No, no, no, not at all, and it couldn’t have been that way because, as you know, as any writer or artist knows, you actually have ideas in process. Not just before and after you have the thing. And collaboration can galvanize that, and you can take those ideas from those in-process things. He would have the picture, I would say something, then the other way, and it would change. I could never unbraid it now. I’ve not worked that way with another person. Such an engaged, in the process, making of a single work, by two people. I’ve never worked that way with another person. Some collaborations are represented by this person does the music, this person does the text, this person does the movement, and each one contributes with the thing they do. But with Tony, from the beginning, it was not you do this, and I do that.

AB: And what was the difference between having performed this in 1988, 89, right?

CDJ: Yeah, 88, 89. 89.

AB: And then bringing it back now. Because it’s done in its original form right?

CDJ: Unchanged.

AB: Unchanged.

CDJ: And that was a decision.

AB: Because what caught my attention is that in this performance you’re interacting with archival materials. With image, with video, with a painting, with a puppet. And nowadays we use these little phones, they archive everything. When we send a video, audio messages. A text.

CDJ: Which we didn’t do in 89.

AB: Exactly, so in a way that part seemed premonitory. What was the difference in presenting the work in 1989 and 2018?

CDJ: I think the difference was stress level. Because I’ve come to appreciate why theater people have a workshop or a preview. Generally that’s done with a new work. Considering that Relatives hadn’t been performed in thirty years, if I had had greater intelligence I would have had a dress rehearsal with an audience. I literally think my hair was falling out because all I could think was, ok, you’re doing it, you learned the piece, it could be your moment of complete mortification in front of a 2018 audience. You’ll come to the end, they’ll turn the lights out, they turn them back up and you’ll hear two people clapping in the background and you’ll quietly leave the stage and have suffered a great humiliation. Does it have legs? Is it relevant? When you are the maker of the work, you don’t know. This is an odd answer to your question. So the difference was, kind of interesting because when I came out on premiere night in Boston in 1989 everything was in the same moment. The people in the audience, the piece, me. It was all in the same moment. Now in 2018 we’re all in 2018 and the work is not.

AB: I thought about that.

CDJ: It was stressful. And we’ve all done stressful things and I think being an artist and making a new work can be like that, you just have your neck out very far. You’re taking a damn risk. I mean you know it, everyone knows it. So this had that element to it, unlike that kind of stress wasn’t back on the premiere time in ‘89. So I’ve been somewhat incredulous. I’ve actually been really thoughtful that it’s been so resonant with people. It’s made me very thoughtful about the people, the piece itself, things I would not have been able to assess only by putting it into world in 2018.

AB: But don’t you think that also the perception of interdisciplinary performance has changed now?

CDJ: Yes, absolutely. I’ve been that creature since I was very young and it wasn’t always a big shared world, interdisciplinary. It’s hard to explain. To me that’s the form, and I’m comfortable with the form. And I have written other works that are me and a screen since Relatives. I did one at Bureau called Speak Chamber. I did one with Lia Gangitano called Scry Agency. So form-wise, that’s one of the things I do. My head was not stressed about the form, just over the content and over the meanings and over the material itself and so on.

AB: And the material, the archives, how did you keep them? Were they damaged?

CDJ: It was ridiculous. Relatives toured. For some reason the world said “come on over here.” You know there’s a cycle to that. I have a set of master tapes, we call them show tapes, of what you use in the show. I have lived in hovels without air conditioning, top floor apartments, those things have been baked and god knows what else. So when the opportunity came I went to EAI (Electronic Arts Intermix) with these pneumatic, I don’t know if you’ve heard of them, they’re very big. EAI, one of their missions is to restore old work, in some cases take care of, so they keep equipment from earlier generations up and running. It’s a very old, venerable wonderful, it’s not not-for profit organization that has been a distributor and restore work. So, some minor fluke happened that my tape hadn’t melted, it hadn’t stuck together. So I thought I was just dropping the tapes off, and John Derringer, who is one of their technical people who would reformat the tape into digital format, said “No, you better sit down, we should just run through it because maybe there’s no work here” *laughs*.

AB: Don’t go home yet.

CDJ: Don’t go home yet! So I sat there and everything was there, god bless. There had been deterioration of a sort. Resolution isn’t quite the word. Color, contrast. So Tony and his assistant, right before the first performance, returned the original contrast and color to the tape. So there was a number of processes. And we were just really lucky that the masters hadn’t melted.

AB: But there was a process of kind of bringing them back to life. Digitizing.

CDJ: The last thing was, there’s something called the aspect ratio. The aspect ratio of 1988 is not the aspect ratio of 2018. So if you play it in digitized format, the image in a present-day screen, there’s black bars in there. OK, that’s not the piece we made. Tony and I are not having it.

AB: So that’s why you had the old TV.

CDJ: It’s a CRT monitor from back in the day, that has that aspect ratio and we were able to locate one and rent one in New York that was big enough. Because it has to be visible, big enough. And we rented a dying piece of technology, who knew? Even though before then we’d had two rehearsals. The tech people at The Kitchen are very good and professional, they were always testing it. I think I was twenty minutes in when it did that first gasp of dying.

AB: You mentioned that each generation has its own technology. And you do some work with old radios.

CDJ: Yes.

AB: So, yes. My question is: What other things are you doing? What is this work with radios? And why old radios?

CDJ: Well, I didn’t plan to be a writer who became a spoken word person and by virtue of that I’ve become a maker of audio, and many different kinds of objects. So that I can be the recorder, the writer, the performer, the editor, the mixer. I think very early on something I didn’t quite know about myself or hadn’t articulated yet was a growing awareness of the intimacy of spoken language. And the intimacy of the space of spoken language. And now that I’ve performed for all these years, you can feel it in the room when you’re performing. I’m sure you’ve felt it. It’s a zone and the audience is in the zone and so are you. And a place where that can happen that isn’t live that I know of, is the radio. And again, it’s an iconic relationship. It’s not something you look at. It’s very domestic. It’s not portable, it’s not with you on the subway filling your head with audio. It’s this domestic solo with an appliance or maybe two people with an appliance, an intimate space like no other. I think, for me, it’s a little bit analogous to reading, which is one of the only other antisocial activities. And I like antisocial activities. Being sort of a recluse. That’s a bit facetious. I think it’s a very particular mentality. And a kind of time, a kind of engagement that’s very unique. I’m not so much fetishizing vintage radios. For some reason I’ve always been interested in Bakelite and these old materials that technology is made of. So I searched out all kinds of places, online, in garage sales, for old vintage Bakelite radios. This is the third set I’ve made and I’ve now moved into radios like this one from the late 40’s. It’s a Crosley, which is a company that doesn’t exist anymore.

AB: Oh wow.

CDJ: They’re very wow.

AB: They’re like art deco

CDJ: I have some that are even more so. This other one is purple marbled plastic and it was an early moment when radios didn’t always have clocks in them that became an associative thing, the clock radio and the alarm and all of that.

Green Crosley. Image courtesy of the artist and Bureau New York. Photos: Dario Lasagni.

AB: That’s so interesting. This is a bit of a detour, but I teach Spanish and they had their first exam and they needed to know how to write the time and I put clocks with different times and they had to write it and they don’t know how to read the time.

CDJ: That’s analog.

AB: I was so shocked because the language was not the problem, the students know how to write the time in Spanish, they just don’t know what time it is in the clock. And it was the first time I encountered that because they’re about 18, so they were born around 2000.

CDJ: Yeah it’s all numerals. I had an analogous moment, we can share this because I know what that shock is like. I teach graduate students in the MFA program at Hunter and I teach an Artist’s books class and there’s a day when they’re supposed to share their projects. So there’s a boy student who had his project and we’re looking at it. And it was a scroll format rather than a codex format and I’m looking at it and I’m saying “Oh, I’ve always, this is not a critique, but I’ve always been interested in handwriting and this is a part of that.” At least six people in the room didn’t know what cursive writing was, what handwriting was, and had not been taught it. They’re no longer taught to go head to hand to shaping the language.

AB: Do you write in a notebook, or do you write in a computer more?

CDJ: Everything, everything. I do have an interest in handwriting because I think it’s somehow inhabited by the person. It is.

AB: It changes a little bit, the syntax of how you write also.

CDJ: It does.

AB: It’s a different line of thought somehow.

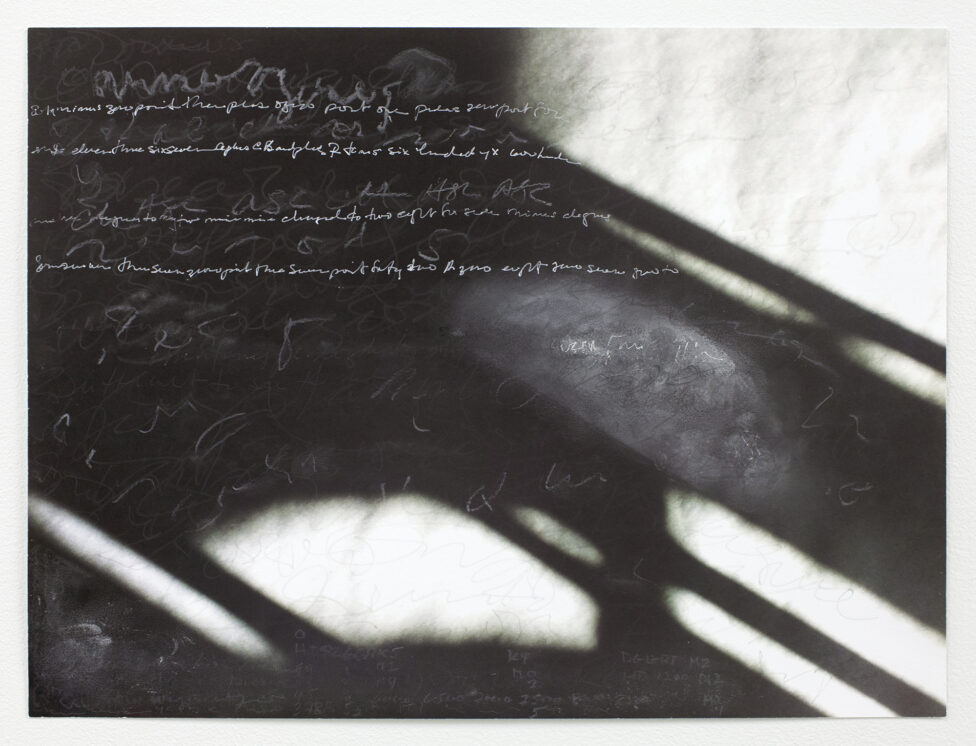

CDJ: It can be. The speed is different, and the back and forth is different. Anyways, I have these drawings they’re part photographs, part drawing. So some part of my work becoming spoken word drew me into technologies and treating language as a time-based material, really. Various forms and projects over the years that I’ve worked in are kind of this natural growth movement so that my own technologies and using them to make things. So, in this case those radios have to be reengineered to play an SD card. And I added LED lights to them that respond to the amplitude of the voice. That’s coding that I can’t do by the way. I have a person who does it. You know, one has the ideas and they are executed by geniuses of electronics. And I have done these things called talking photographs.

AB: I think I saw some of those online. Show me.

CDJ: Well it’s just a still in a frame, it’s a digital frame, so they have a sensor in them, so it goes into sleep mode and when someone comes near they wake up and they play. So that’s about a two minute work. It’s an absurd pairing, an image that’s a still photograph and something that’s time-based. You know, a text, but I like it.

Ionics by Constance DeJong. Image courtesy of the artist and Bureau New York. Photo: Dario Lasagni.

AB: It makes me think of, and this is my last question, but I read somewhere, I don’t remember where, that you and Kathy Acker would meet and talk about verb tenses? And that resonated with me because I teach language and my favorite thing to teach is verb tenses. It’s much more entertaining than a lot of the other aspects of language teaching which can be very tedious.

CDJ: Which is just vocabulary!

AB: Exactly, or verb conjugations, that in Spanish are very tedious. But verb tenses…

CDJ: Oh I love you that you understand that! Most people read that and they think “Oh my god! How boring, what nerds!”

AB: And it’s been a challenge for me to learn how to teach them. But it’s by far the most fun part to teach for me. So I wanted to ask you what was it that you talked about? What was it about verb tenses?

CDJ: Well it also pertains to, Kathy was one of the few writers I knew that shared an interest in the mechanics of writing, the structural mechanics. You can be less interested in that as a writer if you write to a convention, let’s say. So we shared that, talking about narrative and making time. So, as she and I shared an awareness of narrative as a time-based form and narrative as a time-based material, you’re going to get to verb tenses, you’re going to get there, because you’re thinking of the narrative as time. You have the opportunity to make multiple times. A past, a future, a participle. It was just going to be a built-in part of that conversation. Linked to, she and I would talk a lot about the POV, the point of view. You know like, if something is gone into the past tense, what generates that point of view? How do you get the past in there? You know what I’m saying, these are like technical aspects, but they’re interesting though.

AB: Yes, it’s interesting. I write mostly performance text or theater and so that for me is very easy because it’s very in the present. But right now I’m trying to write something that’s more in the format of a novel and I’ve not been able to finish it because of a struggle with how much time is in the novel. I know what I want to happen, I know these characters, I know who they are, I just don’t know if it’s a year, if it’s five, if it’s a week.

CDJ: Don’t think about representing clock time. I’m going to become, turn that off.

AB: Ah?

CDJ: Turn that off.

AB: Ok, we’re done?

CDJ: This is shop talk time.

Constance DeJong in Relatives. Photo courtesy of The Kitchen.