In my time at Critical Correspondence, we have published several pieces that reflect on the nature and need for class series that let us notice what we’re practicing. That activate our values of experimentation (not technique) and learning (not instructing). We create class series in bursts because this is often how our thirst and our capacity works. In May and June 2024, Jennifer Nugent instigated a class series at Triskelion Arts in Greenpoint, Brooklyn called Dream Space / Activating Pedagogies. The classes were taught by Leah Wilks, James Barrett, Kimiko Tanabe, Mawu Ama Ma’at Gora, and Ogemdi Ude.

Jenn wrote the following proposal for the series:

“Considering, gathering, ways in which to activate spaces or workshops that are engaging your most immediate needs, thoughts, and current self.

A space where one is not exactly sure what might form. A space to gather. A space to not get “better, or improve” instead go deeper towards where we are. To improvise. To nudge capacity; to engage with, to rest, replenish. Activating improvised formations, communing together, and making time for this precious proposal. Tender hearted explorations, giddy realizations, intimate endeavors and sensations that reveal the aliveness, the beauty, and the uniqueness of being human. Breath and desire, always dancing; knowing this can take many forms and there are so many dances to be danced.”

Below, Jo Warren reflects on attending and being shaped by each teacher’s offerings. We’re grateful to publish this record of action.

—Londs Reuter, CC Co-editor

I wonder:

What does it look like to resist the ceaseless call to “get better?”

Can we get deeper?

Can we uncover?

Can we learn new ways to be together? To love? To share? To learn and grow and expand outward not upward?

Can we relinquish competition, scarcity and judgment?

Can we revel in the brilliance of one another?

Can we see the value in every person we come into contact with and feel how just knowing them changes us on a cellular level?

Can we find new forms of resistance together?

////////////////

Jennifer Nugent was one of my first dance teachers. I took her “Intro to Movement” course as a college freshman—now over a decade ago—which was my first true foray into studying dance. At the time (as a “non-dancer”), class was a spiritual practice. It was a way to locate my body in relationship to other bodies, to relinquish fear, social anxiety, and habits of intellectualizing in order to access a state of being-ness. In my first month in Jenn’s class, I wrote:

“I can feel that pulse between us – that organic and unavoidable force. We convince ourselves that we are separate, but we are inherently so intertwined in the most profound way. The willingness to move yourself freely and organically – without judgment – reminds us of that connection. Also the willingness to touch and be touched – to feel fully the aliveness of another being in proximity…”

As I continued to study dance, I began to approach dance class from an extractive place—a desire to get or gain something. I thought if I took the right classes and approached them with enough rigor, I might legitimize my body and my dancing. I might find a way to “belong.”

We’re taught to believe that discipline and rigor yield reliable results – but what in this world is truly reliable? What about a living body is a given? What are the ends of discipline when the bodies we are training, shaping, disciplining are aging and dying?

As we reckon with an ongoing global pandemic, climate collapse, genocidal violence, state repression and the systemic lack of care for human lives, I have begun to approach class differently. Instead of coming to class with a linear desire to gain skill or approval, I approach class with a longing to feel more, experience more – to be closer to other people, myself, and to life. I come with a longing and need to be with other bodies in non-codified ways, to be gentle, playful, rough and vulnerable. To locate myself as part of a collective body.

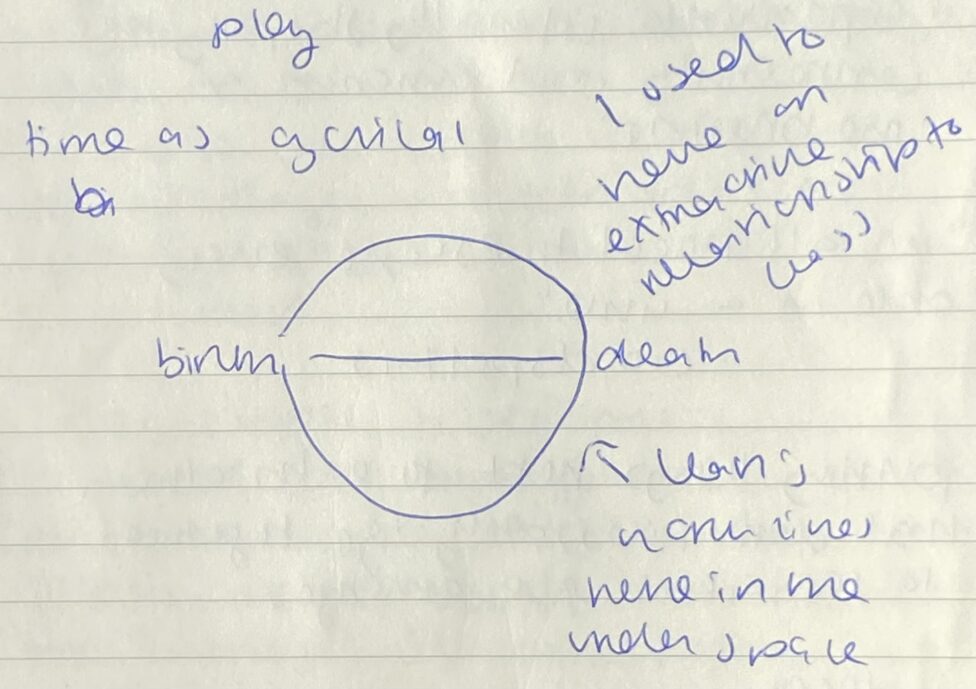

The first class in the series was taught by Leah Wilks. She asked us to consider time—not as a linear process, but a cyclical one. In her class description, she asks: “How might non-human life cycles, decay, electrical impulse, plants, and dancing all be the same thing?”

“Birth is here,” Leah said, pointing to an imaginary dot in space, “and this is death” gesturing again to another point. She drew an arch from birth to death and then death back to birth, creating a circle in the air – “my work is sort of here,” she says, pointing to a place near death. “I’m interested in this under space, the movement from decay to reemergence.” The dark, the unseen, the unknowable, the fertile, the potential.

Within the first 10 minutes, I was in a dance with someone I had never met. Initially tired, heavy-limbed and resistant, I found myself suddenly moving, pulling, rolling, diving, laughing, lifting and being lifted. We had hardly spoken more than a few words to each other, but were communicating fully and listening deeply to one another with profound care and trust.

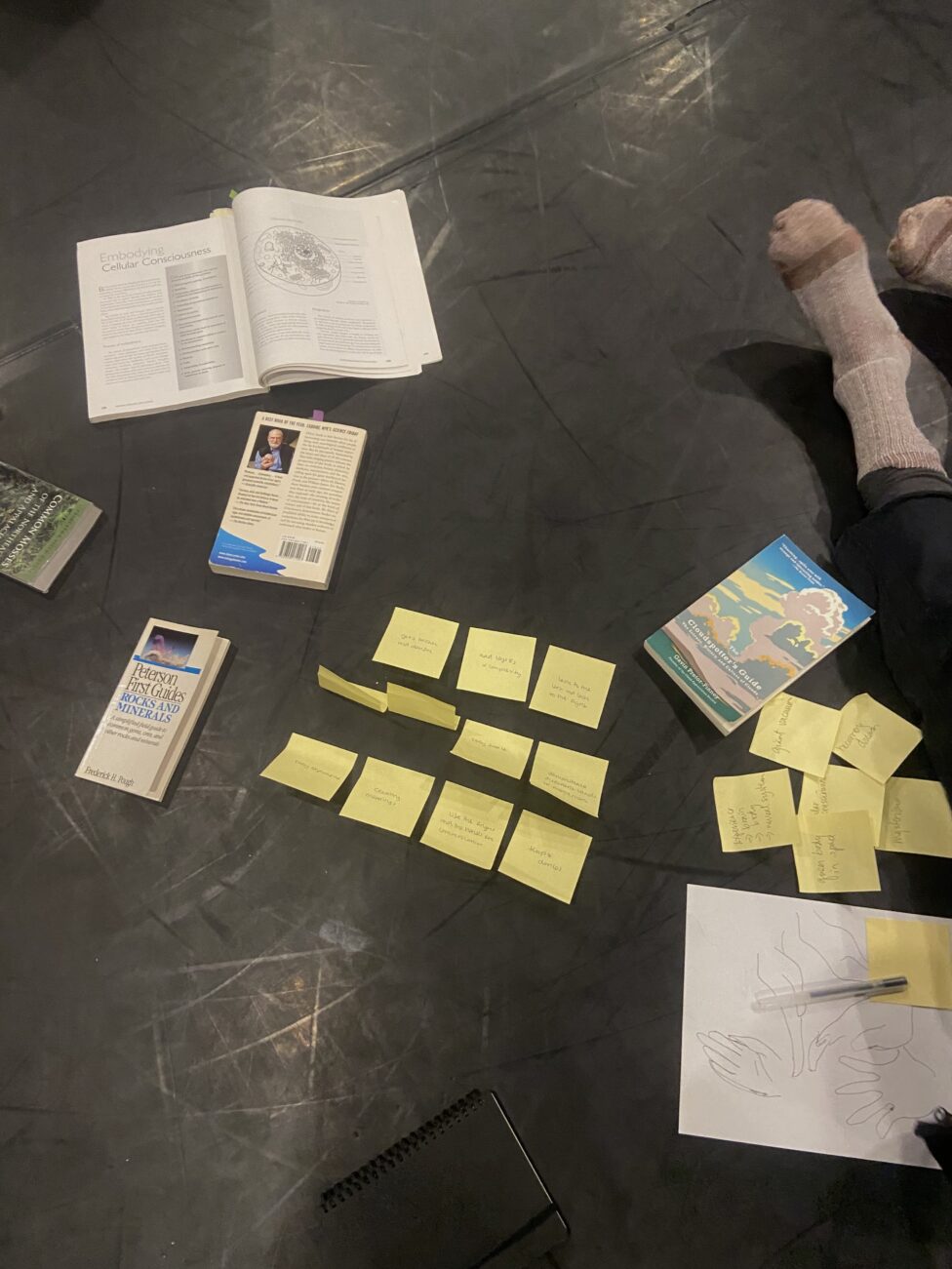

After an hour of dancing, Leah opened what she called “the library,” laying out books of all kinds and inviting us to follow our desires and curiosities – to read, to look, to collage ideas. There were books on weather, somatics, theory, revolution, lichen and on and on. After we read and gathered and scratched our own personal itches, we were invited to pair up and share our “research” with a partner. I was struck and moved by how different our interests and desires were – by the specificity and expansiveness of the minds of each person in the room and by what we all had to say, offer, share and show. My partner had honed in on hands. After sharing our research, we gathered words and phrases and made short dances from them. More brilliance, more surprise.

Class is a place where we get to become a detailed witness.

We get to get to know each other in a more expansive way, beyond the codified confines of a “workplace” or other kinds of social environments.

We get to touch and be tender without it being “romantic” or “sexual.”

We get to see bodies in a new way – outside of order or value production.

We get to see each other – how we move, think, interpret the world. We get to see each other’s vulnerability and witness our individual and collective brilliance.

////////////////

At the start of Kimiko Tanabe’s class, she told us from hands and knees that “warming up is part of the ethos.” The warm-up involved pairing off and holding our partners heads. First we asked: “can I hold your head?” This sensitizing warm up was a way for us to attune to the shared humanity in the room, to look at each other’s morning faces, to become vulnerable and animal, to support and be supported. I thought about how rare and special it is to feel the entire weight of someone’s head in your hands—especially a “stranger.”

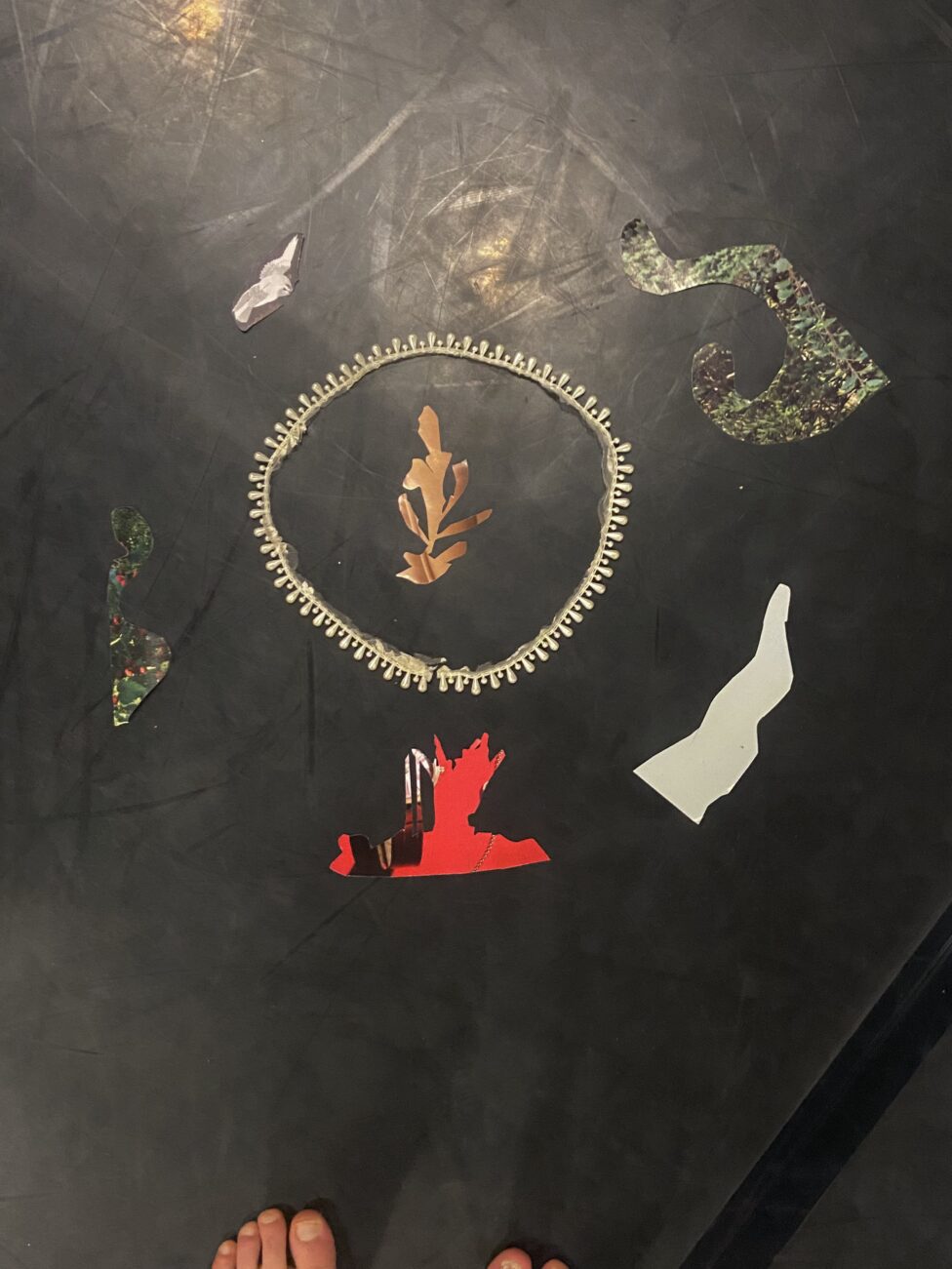

Later in class, Kimiko had us approach a pile of shards, fragments, scraps, bits—orange, blue, lace, black and white photographs, limbs, clouds—and asked us to create a collage of our current energetic state. Everyone slowed down, spending time with the fragments, with their bodies, listening, choosing, arranging. After we’d all finished and admired our images, she told us to dump them and make a new one. There was quiet… “It’s a practice in impermanence,” she reminded us, “there’s freedom in impermanence!”

Class is a world-making endeavor. The facilitator gets to usher in a microcosm of the world they want to live in. Gentle group logics emerge from a kind of cellular listening. We get to access parts of ourselves and be witness to new edges of our own being. We get to witness ourselves in relationship.

“There is space here. There is movement here.”

That was the refrain of James Barrett’s class. We whispered it to ourselves, to each other, and were reminded as we moved: “there is space here, there is movement here.”

Later in class, James had us give each other tours of the studio space, describing objects as something they decidedly are not. “Aw, this is my puppy” someone said, pointing up at a speaker attached to the ceiling. “This is the dissolving glue that is holding my life together,” someone else said, dragging their finger along the place where two pieces of marley connect.

The practice deepened, and we were invited to begin to “yes and” each other. (“This is the window I used to look out every morning before school,”

“Yes, and I used to stare back at you from the other side.”)

Worlds began to be created. Shared logics, new characters and creatures entered the space. My partner went to the bathroom and James and I stood back and quietly watched the pairs in the room: deep inside imagined realms, complete realities, laughing and playing, trying on new voices and physicalities. One pair rolled together on the floor in a unison near-wail while another reached wildly up toward the ceiling toward something we could not see. “Aww… everyone is a child.” James smiled, “This is exactly what I wanted.”

Class is an opportunity to locate dream logics and follow them to their natural end. Or perhaps they never end and we can follow and follow and follow – never knowing where we’re headed.

////////////////

Ogemdi Ude takes the prompt of dreaming somewhere else. In her class description, she cites a nightmare in which she is “put onstage with a dance company in front of hundreds of people, and everyone except [her] knows the choreography.” She offers: “we will draw from that fear and learn how to use forgetting to our advantage,” inviting us into a space of agency and lucid dreaming that allows us to transmute our nightmares into possibility.

What happens in that edge space? What happens when instead of shrinking, hiding, retreating – we stay? What dances can be made?

////////////////

For Mawu Ama Ma’at Gora, a dreaming practice is agency. It is relinquishing ideas around failure and embracing a wider realm of possibilities – “not colonizing my own dreaming practice,” not tainting it with frames of whiteness and Western supremacy – stretching beyond the frames and limits we’ve been served.

”Even the fact that we’re in a ‘classroom’ is colonized,” Mawu said in a voice memo. “[This] forces me to have a bigger dream […] to not be afraid when I get to a point where I don’t know… and knowing there are possibilities even when I brush up against the unknown.”

For Black, brown, indigenous, queer and trans people: “dreaming is an anchor. It’s salvation.” For Mawu, dreaming is not ethereal or leisurely – but rather a necessity, a discipline in itself. It’s a form of knowledge, practice and rigor that isn’t about yielding reliable results, but about moving into a living present that sustains us. A collective present.

Our well-being is inextricably tied to the well-being of the collective, and yet we are led to believe that the only way to survive is to compete for resources and think of our lives as separate. It’s impossible to feel all the threads connecting us forward and back in time and space and all the massive, invisible forces acting on our lives. Often it’s easier to sink into isolation and despair than it is to reach for those threads with our imagination and feel into our longing – a longing so great it threatens to tear us in half.

I wonder:

What are we practicing? What are we moving toward? What tools do we need for a future that remains so precarious and uncertain? What kind of excellence will serve us?

How do we return to a place where class is about discovery, delight and forging new ways of being together that feel expansive and joyous? How do we bring more beauty into the world instead of more violence?

Interacting with Dream Space—Jenn’s larger vision and the pedagogy of Leah, Kimiko, James, Mawu and Ogemdi—I find myself with more questions and fewer answers. Over a decade after discovering the world-shifting capacity of dance class through Jenn’s lens, I feel grateful to be feeling my way in the dark once again. I’m dreaming of more spaces like this where we can experiment with new collective realities and inhabit spaces of inquiry, integrity and meaningful care – where we can practice something radical and quiet and beautiful together.