On Sunday we all woke up to the largest, but by no means the only, hate-fueled mass murder this year, and the largest mass shooting in this country since Wounded Knee. I need some time to be alone with grief, but, as this festival helped me remember, I also need community to heal. This festival structured the rhythm of my week; I am lucky right now to be doing work that allows me to put other things aside and inhabit that rhythm. I am also lucky in my community, and grateful for the gift offered up by the curators of this festival, Tara Aisha Willis, Eleanor Smith, Elliott Jenetopulos, Aretha Aoki, and to Anna Adams Stark, Randy Reyes, Levi Gonzalez, the entire staff of Movement Research, and every performer and healer who brought their bodies and their time to these shared spaces.

These people know well that though all of us need to heal, not all bodies are equally threatened by violence and exhaustion. At the start to each event, the curators offered up this reminder: “We want to acknowledge that we are on stolen land, labored over largely by unrecognized and stolen people. Recognizing that healing and care are ongoing processes, we offer reverence for what has come before.”

The arc of this festival began last Monday night, as I moved through the first house created by Liliana Dirks-Goodman, feeling birthed into a new and safer space. In groups of two and three, overlapping, coming together, and coming apart, dancers improvised performances in response to one another and to the space and moment we all shared, held by the sounds of Julia Santoli. As Randy Reyes, Lily Bo Shapiro, Anna Adams Stark, Marguerite Hemmings, Justin Cabrillos, Anna Carapetyan, Ayano Elson, Sarah Maxfield, BASHIR DAVID NAIM, Marissa Perel, and Michael Mahalchick enacted this public intimacy, I was watching communities form. As Juliette Mapp, Donna Uchizono, luciana achugar, Kayvon Pourazar and Natalie Green come out to dance their joyful appreciation of Levi Gonzalez before he moves to Los Angeles, I am watching a community celebrate itself.

Appreciating the communities of other bodies in a space transitions to asking how we form our own communities. The doulas, caregivers, bodyworkers, and healers who shared their insights on Tuesday asked us to think again about how we care for one another, specifically in the liminal spaces between birth and death. As Anna Carapetyan, devynn emory, Robert Kocik, and iele paloumpis answer questions posed by Risa Shoup and the audience, I find myself thinking that the boundaries and connections between people are always liminal spaces. I can no longer remember who said what, but written down in my notebook from that day are the lines: “there are times to be closer and times to be further apart” and “reach out as far as you can go to establish the network that you need.” How do we form the communities that will both give us what we need and allow us to offer the care we long to give, how do we navigate consent and needs that are not our own, and who has access?

Volunteering at BkSD before Wednesday’s performance meant taking a step into the work of maintaining a community. I arrived, squelching with rain, at 2pm, and scrubbed floors, laid stones, shoveled dirt, and planted flowers. By the end of the day my body was dry, and dirty, and exhausted, and replenished. Mariana Valencia made me laugh with the joys and aches of queer childhood, jokes, campfire stories, and growing pains. Drawing not a line but a curve on the floor in tape, she made her own space, but that space was open.

Then, Jumatatu Poe comes out and introduces himself and his co-performer William Robinson. Explaining the work to us, he says that he has performed it twice before, but always felt that there was something missing from the audience. This time, he tells us, he is going to bring his own black friends to the performance. In case the white members of the audience need permission to laugh, or feel a certain way. I don’t need to look around to know that most of the audience is white like me. His friends are projected on the far wall, a group of people watching from the other side. The wall is too far away to see their faces, but they watch us as we squint across the room. Or, they don’t. They aren’t there, really, but the screen makes both them and their absence present. Partway through the performance the screen has played itself out. The dancers run through sequences of movement, smiling out as the melancholy lines “Please fall down, testing sounds” and “Faith in prayers will make you see your bones” ring out. The incongruity continues as they push themselves to the point of exhaustion, ending a sequence only to start anew, performing exhaustion. At the end of the night they hold each other, speaking into one another’s mouths: “What is it you want, is it my sameness or my difference?” and then “My sameness is my difference.” I can’t tell who speaks which lines, they come from the same place, they come from different places.

If Wednesday’s event asked us to bring our selves into the communities we had watched and listened to on Monday and Tuesday, Thursday’s healing workshops allowed us to look at and care for our selves in new ways. Regina (aka Wolf Medicine) took time to explain the relationship Ayurvedic medicine teaches us to see between what we eat and the health of our skin, and I found myself casting back to Tuesday’s event. What do I allow to enter my body and why? What will harm me if I let it in? How do I keep myself healthy, and how do I balance what I need from the world and what others need from me?

In my private somatic therapy session, Weena Pauly asks me to reconnect with what my body already knows. I am sitting on a mat facing her, and she asks me to close my eyes. You can open them if you feel you need to, she says. The darkness feels spatial as she asks me questions. I feel like I might fall, but then I realize I am falling into myself. How is your body feeling right now? What are you thinking? What emotions are you experiencing? Gratitude and a little fear, I tell her. I am so far inside myself that when I open my eyes and walk out into the street, I think they might still be closed.

On Friday and Saturday, when we come together as groups to share in performances and readings and reveling, I think the festival has taught us to come together differently. I am bringing myself in a different way when I show up on Thursday, with my carefully underlined copies of Audre Lorde, Silvia Federici, and Fred Moten and Stefano Harney’s essays. All three of Liliana Dirks-Goodman’s houses are here, and I move around them before I take my seat, holding the rose and message Sarah Maxfield has sent to us all. “What you are doing is enough,” I read. The space is shifting.

We sit in a circle and begin talking about Silvia Federici’s essay on precarious and reproductive labor as mayfield brooks, Justin Cabrillos, Marguerite Hemmings, and Ni’Ja Whitson begin to move around us. Tara Willis and Lilliana Dirks-Goodman, gently guiding our circular, multiple lines of inquiry, ask us to think about the labor that goes on underneath, below the labor that is often most visible. Under and through the houses, the performers participate in the conversation with their bodies and mayfield brooks calls out words, thrown into the conversation when we need them, where we can hold them. How do we reproduce our communities, how do we teach ourselves and those we care for to refuse a system that hurts us, without ourselves doing damage?

As our responses slowly conclude, Rihanna’s “Work” begins to play, Marguerite Hemmings asks us to get up: “You better work.” The circle slowly moves inward, forming a line dancing through the first house as we slowly come back around, remembering that our bodies are part of what we bring when we think together.

We come back to talk through Fred Moten and Stefano Harney’s essay on the undercommons. We don’t know what that is, or where, or who, or how to get there, but we’re working on it, cultivating our own practice of studying together, underneath the work that gets acknowledged by the institutions whose resources we steal, giving ourselves the resources we need to do this work. We know it was never theirs anyway. Some of our bodies, one person says, are always fugitive: it’s not a choice. “The subversive intellectual came under false pretenses, with bad documents, out of love.” Fred Moten and Audre Lorde agree about love, but she reminds us that when we come with our love we come with all our pain, too. “And there are no new pains. We have felt them all already.” That entanglement is dark but it lifts us up. There is a lot to fear, but none of it is new. We can bear the pain that may come because we have felt that pain before. All night, we have been wondering how to imagine something new. Poetry, she seems to suggest, is where we can transition from what feels impossible to what becomes potential. It is the threshold of action.

That action enters the circle when Ni’Ja Whitson steps in. I realized, they say, that we’d constructed a boundary or a limit, with the circle where discussion happened and the dancing outside of it, the intelligence of the mind and the intelligence of the body kept separate; and that seemed kind of fucked up. mayfield brooks tells us about feelings, beginning inside one of the houses, standing and facing away from us, drawing on their body with red lipstick and explaining to us that Audre Lorde was an affect theorist. Breaking through that boundary, they brought their bodies into the circle, and then all our bodies were there.

On the last night, we are tired and full of joy. This night is a performance and a party, and we know now that our bodies are required for both. This week has carried me beautifully and devastatingly out to other people and far back into myself, so that now, showing up with other people, I bring myself more fully. I am ready to be here with you.

The night begins in stillness. Michael Mahalchick, buried under a sheet of silver that matches the foil-covered walls, tells us the story of the boy who cried wolf, “a good boy,” “an irresponsible boy” as childhood images swim by on the projection screen. I am feeling for this best, irresponsible boy when he stands up in a wolf mask. Who is the boy, who is the wolf? Maybe I feel for the wolf in us, too.

Lily Bo Shapiro crawls into the room, and Jonathan Gonzalez follows, carrying a light that casts her shadow, a slow-moving vigil. We are watching over, too, as she begins to roll across the floor, uttering sounds at the edge of what can be said. When she turns out the light, we are in the dark, still together.

Social Health makes us move. Ivy Castellanos, Ayana Evans, Zachary Fabri, Maria Hupfield, Geraldo Mercado, pace around the space, each intently engaged in their own activity. There are multiple urgent things happening at every moment, they remind us. We can’t keep track of it all, and we are also in it. First one and then another audience member is called up, engaged in something they don’t know the rules for. What are the limits of a performance? “Where are we going?” the performers call out to one another, but the response is another question. “What will we do when we get there?” There is foil and danger-tape scattered across the floor. We make a mess and we clean it up. They begin to prepare to leave, but we aren’t all always ready at the same time. Zachary Fabri asks again, “Where are we going?” and isn’t satisfied with the answer. “But really, where?” “How will we know?” “What will we do?”

Jonathan Gonzalez needs to get into it. He keeps telling us, he keeps trying. He asks the audience for help. Do you feel it? I’m almost there, he says. He strips and spins around. Is he there yet? An audience member (or a performer?) rolls him in tarp. Is this what we were getting ready for? How do we prepare for an ending? Do you feel it?

We all filter out, and a small crowd waits for the next performance to begin. Becca Blackwell and BASHIR DAVID NAIM welcome us back in. We move from the haunting violin songs of Mark Golamco to Hye Yun Park a.k.a. Ancient Toddler the Clown’s painful, hilarious performance. She plays a toy piano, racing mounting boos and mounting panic. After a great day, after an awful day, she tells us, she feels compelled to eat fried chicken. She takes of her skirt, and begins to rub a dildo against a large, fabric vagina, telling us her story, eating fried chicken, and sobbing. The person next to me is bent over in laughter, and I’m mesmerized. Applause begins to sound, and then there is our applause as well, and I feel complicit in something without being quite sure what. Which is not, actually, unusual.

The dance break between performances is what I needed. My body needs to move, and I’m grateful for this moment of release, of coming together and celebrating one another. I find some of the curators and cheer with them, for them.

Becca Blackwell hula hoops while telling us about their childhood discovery of porn, and then Zavé Martohardjono comes out to help us work on our self-care regimen. Just 30 seconds a day, he tells us. Your self-care, too, can be quantified and commoditized. “When one of us wins, we all win; when one of us wins, we all win; when one of us wins, we all win…”

Cae Monae enacts a ritual. Three members of the audience hold candles, experiencing their divinity as she shares hers with us. There is blood, or is it paint, on the floor.

BASHIR DAVID NAIM closes the show, singing a digitized, extended rendition of Whitney Houston’s “I Will Always Love You” against projections of kombucha and yoga poses in fake clouds. It isn’t real; it’s all the realness I want. Sometimes healing is painful, sometimes it’s angry, sometimes it’s hilarious, sometimes it’s quiet solace, sometimes it’s a party. In the words of my good friend this week:

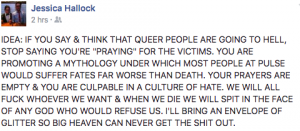

I am grateful for all the healing and transformation last week brought into my life; I’m bringing it with me, we’re going to need it, I’m going to need you. And glitter.