Michael Bodel: You mentioned that you visited The Philip Johnson Glass House in Connecticut, and that his transparent architecture in the natural environment was an early inspiration for the dance. Can you talk a little about those earliest ideas?

Ivy Baldwin: I had a surprise trip to The Glass House, it wasn’t an intended research trip. It’s so beautiful. Have you ever been?

Michael: No, never.

Ivy: Because of the glass there is this beautiful, unsettling thing that happens, where you are seeing reflections of things that are in another reflected surface. There are all these images piled on top of each other that are so complex, but yet absolutely crystal clear because of the glass. I found this space to be so inspiring, and the woods surrounding it paired next to that tiny modern piece of architecture. It’s just two completely different things sandwiched on top of one another.

The Philip Johnson Glass House, photo courtesy of www.nycitycures.com

Michael: So what sent you thinking in the dance direction, instead of that just being an experience?

Ivy: Well, it coincided with me having to write a paragraph about what this dance was for New York Live Arts [laughing]. I was required to write a paragraph for marketing before I had even started rehearsing, so I had no idea what this dance was going to be about. But two days before, I had had this really inspiring experience, and that place just kept coming up: how it made me feel.

I have a friend whose son is a photography student, and they live right near [The Glass House]. So, his son had taken, over the years, all of these photographs of the house. I’ve spent a lot of time looking at them.

Michael: Then what has happened when you stepped into the studio and started to play with these ideas on bodies?

Ivy: When I went to the studio, we started making things that played around that idea of something very modern paired with wilderness. And that [theme] has stayed throughout: these clean architectural studies of movement paired with this feeling of being wild. I think more of the architectural has stayed. It’s gotten simpler and simpler.

Michael: I was thinking about Modern architecture, because I knew that was an inspiration for the piece, and how one iconic aspect of Modern architecture is the pared down, skin-and-bones aesthetic, which is very bold and in-your-face at first, but then leaves a lot of room for seeing the space around and seeing the space through. Then thinking on your previous dances, I feel like I see a clear connection with some formal elements that you have in your dances. In Here Rests Peggy there’s that section with all the battements, or the section with the slaps, or the winks. There’s a very clear element, but then either through duration or repetition, we start to not see that element anymore. Instead we start to see the person dancing, or notice three people in dresses, or see Lawrence [Cassella]. Can you talk a little about these formal elements in your work?

Ivy: Are you asking if that is prevalent in this piece as well?

Michael: Just in general.

Ivy: It’s a theatricalized version of real life: blinking or hitting. That’s always been interesting to me, but this piece just feels so different. It is much simpler and more about the movement and the body conveying the drama and tension. The obvious drama or theatrical elements aren’t really there; the structure is very different. There aren’t these “events” that I think my work usually has. I didn’t want to do that with this piece, or it wouldn’t let me, I should say. I kept having to cut things that were like that, and [the whole] has become far more important. Everything is dependant on everything else in a certain way. The whole picture is what every moment has to add up to.

Michael: That seems very architectural.

Ivy: Yes, for it to stand. I’ve been thinking a lot in my work, about safety nets and what are my safety nets. What are the things that I know work, or that I know I personally remember about a piece, but they’ve started to feel too easy for me. I’ve been thinking about how to remove those things without removing what makes your work special to you.

Michael: It seems you’ve been doing a lot of removing [laughing].

Ivy: Yes, I’ve been doing a lot of removing. I’ve removed and removed, and the piece is very sparse.

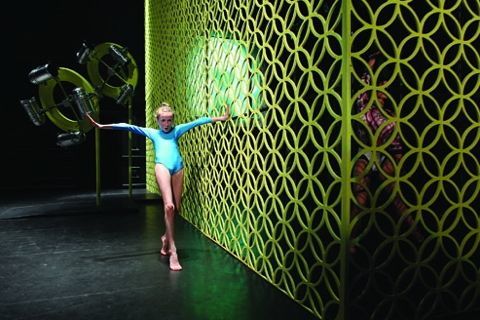

Ambient Cowboy” in rehearsal, photo by Nola Lopez

Michael: It’s interesting that you talk about avoiding specific catchy units, because while your work has had those in the past, the words that come to my mind [in describing your dances] are more like “uncanny” and “mysterious.” Can you talk more about wanting to create sections that evoke, but don’t describe themselves too much?

Ivy: I’ve been thinking about removing “telling” and giving clues about how the audience should feel—about trying to remove that and letting it resist the more traditionally theatrical. This piece has much less of that.

Michael: Does that mean removing the humor? [laughing]

Ivy: [laughing] Yeah, this dance isn’t funny. Sadly! We made a lot of funny stuff, at least some, but it just didn’t fit. And all the speaking has been cut.

Michael: Are we going to get to see ###em outtakes?

Ivy: When we yell and sing and make jokes? No! For me, it’s been about resisting those things that come easier to me, which is scary, but really exciting.

Michael: You perform in your own work, and you also work with a lot of the same go-to collaborators. These are seasoned performers and each very unique. How do you approach the idea of performative presence in your pieces? Are there conversations that you have, or exercises? Or do you just let people be who they are, and you don’t address it, but just hope to end up on a similar wavelength?

Ivy: A lot of the time I try to cultivate something about that person’s own way of performing and interpreting the work. That’s really fascinating to me. We spend months together, and I work collaboratively with them making the material. I talk and think a lot about imagery and use imagery as a way to create movement and then in how to perform the work. But, the way the work is performed is often how we create it from the beginning. Context then colors everything and new ideas emerge as to what different things mean in the bigger picture. I direct them, especially now in these last two months, but I don’t do a lot of performative exercises. I usually tend to pick people because I love the way they are on stage.

Michael: This may have just been grantese, but you describe your work as being “collaborative documentaries” of you and your performers’ lives.

Ivy: No, I believe that, as well as wrote it in a grant! [laughing]

Michael: Can you talk about the way that life enters into your work?

Ivy: I feel like, if I’m present and they are present, you can’t block out life. I guess some people stay super on-track with what they’ve decided something is going to be about, but that isn’t as interesting to me as a maker of things. [I’d rather] let life filter in, be it my life or their lives.

Michael: Who are some choreographers you’ve seen recently that have really moved you?

Ivy: I love Tere O’Connor; I have my whole New York City life. His work always just makes me feel so much, and I always feel incredibly inspired. I just saw Jodi Melnick, and she is just one of the most beautiful performers. Watching her dance made me want to hurry and call all my dancers and get in the studio. I still think about Sarah Michelson’s Dover Beach.

Non Griffiths in Dover Beach, performance at The Kitchen, 2009. Photo by Paula Court.

Michael: I wanted to end with more of a brass tacks question; it has to do with career stuff. You work very hard at making dances, so much time and energy, but you also work hard at advocating for yourself and getting funding. What advice do you have for younger choreographers or choreographers entering the field here in New York for staying positive, navigating such a dense environment of choreographers and locations, and for finding ways for your art to be sustainable alongside your life?

Ivy: That’s a good question. In the beginning I showed my work in every possible place that would let me, as frequently as humanly possible and as a contract would let me. I just put myself out there over and over again, and kept inviting people over and over again. Until I cracked through. You have to just get your work out there, and show it as much as possible. It sounds silly to say, but I think that’s all you can do. Go see as much as you can, talk to people. Make sure you have a supportive community of art-makers and friends, then just put yourself out there.