Interview date: November 24, 2014

Molissa Fenley, whose choreography has been an important element in the fabric of New York City dance since she formed her company, Molissa Fenley and Company, in 1977, sits down with Richard Move to discuss her oeuvre. A vast body of work that extends across multiple decades and geographies, Fenley elucidates her recent seasons at Judson Memorial Church (2014) and New York Live Arts (2013), which included both premieres as well as the revivals of early works from the 1980s, a complex period in New York dance that was distinctly thriving while also full of incomprehensible loss. Move, whose own work enigmatically dances in the fecund space between choreography and its embodied archive, engages this early period in Fenley’s dancing and dance making, mining historical contexts, informal anecdotes, and personal memories, all of which speak to the upcoming publication of her book, Rhythm Field: The Dance of Molissa Fenley, to be released July 2015 by Seagull Books.

____________________________________________________________________________________

What began as a conversation focused on Fenley’s New York performances at the Judson Church and New York Live Arts, quickly took an urgent turn toward encompassing a kind of career retrospective, albeit broad and sweeping. Our discourse revealed lost visual art objects by Francesco Clemente, lost costumes by Jean Paul Gaultier, lost scrapbooks made with Ryuichi Sakamoto and a dance dedicated to Arnie Zane entitled, In Recognition, with no recognizable archival remains to assist us in telling its story.

As our dialogue transpired, it exposed not only missing documentation and incomplete historical anthologies but also a broader range of topics, from age, to gender and an unsung heroine of Futurist Art. We both, in Jacques Derrida’s words, had “Archive Fever” and our temperatures ran hot. We deemed it necessary to retrieve what we could: a screen shot taken from a deteriorating VHS recording, the inclusion of photographs capturing Fenley from 1982 to the present. All with the hope of providing the reader a synoptic, digital document of Fenley’s four decade career.

Our exchange also uncovered a wealth of treasures. A body and body of work that renews and revives itself with reservoirs of energy. A body and body of work that communicates across hemispheres, beyond geographic boundaries, beyond spoken language and beyond gender binaries. A body and body of work that communicates, empathically, across species. A body and body of work that achieves ecstatic states through acceleration. A body and body of work, rife with progressive idealism. And, ultimately, an embodied knowledge that is, perhaps, Fenley’s most reliable archive and archivist.

-Richard Move

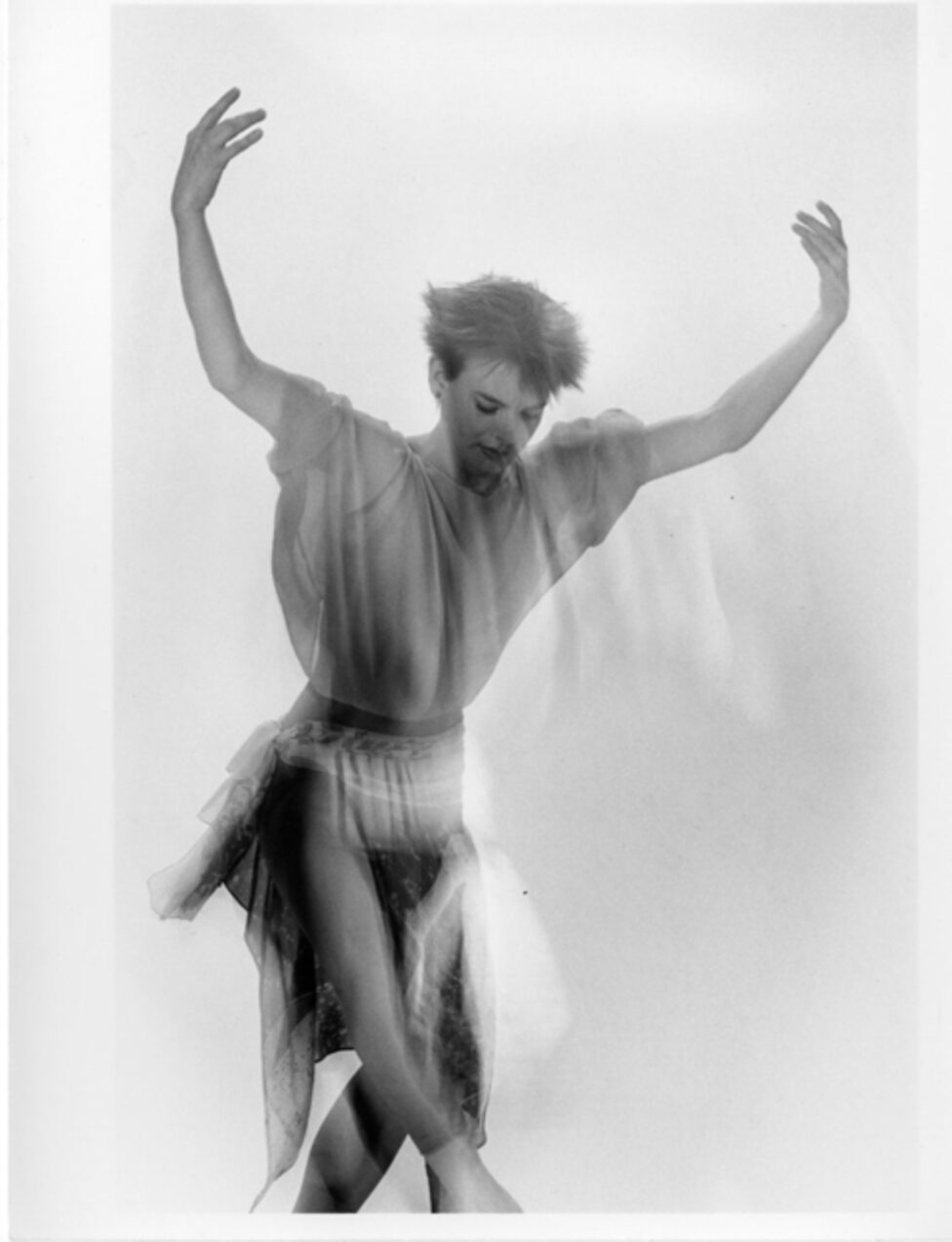

Photograph by Timothy Greenfield-Sanders

Richard Move: Let’s go back to this Eureka/Second Sight moment, when you discovered the male manifesto of the Futurists at the Guggenheim and arrived upon a female. And, how that drew you in to want to know more about her and her imagery, as you have in your Judson program notes, “…from images of Futurist dancer Giannina Censi.”

Molissa Fenley: Yeah, I’m not sure what it has to do with Eureka. Eureka is 1982.

RM: With music by?

MF: Peter Gordon.

RM: And Second Sight?

MF: Second Sight is part of that.

RM: I’m just calling up titles of your works and associating…You had a “Eureka” moment when you came across the female among the male futurists, and the male manifestos, and you arrived upon the singular female.

Eureka, 1982. Photograph by Jack Mitchell.

MF: Absolutely, I did. Firstly, she was one of the only dancers. Almost everything else is a theatrical situation. This is someone who is actually doing something very physically movement oriented. And, what she’s doing is so peculiar. In my mind it goes back to the Greeks. She has this discus man position that she does. It reminds me of the sculpture of the discus man with his discus down by his knees and his hand like that. She has positions that are like that, she has positions that are kind of coy, she’s up on relevé and has her leg in a parallel passé and her hand is sort of like this. So, the angle of her body, I love those angles… where the hand is, there’s a shift, where there’s a wrist, there’s a forearm and everything’s always really in different planes. I love that.

Redwood Park, Part 2, 2014. Photograph by Reiko Yanagi. Rebecca Chaleff and Matthew Roberts.

RM: Do you feel simpatico?

MF: Yeah, oh yeah. I admire its peculiarity. I felt this is really interesting, I’ve never heard of her before. I can’t say I’m an expert on Futurist Art but I’ve never heard of her before. She was a discovery for me personally. After looking at the book, I came home, googled Censi and came up with a couple of other images. But she was really very obscure. She had worked a little with Marinetti. I think she was one they kind of admired in a way.

RM: Now, in the context of your own career, do you identify, would it be possible for me to speculate that you identify with Censi? In terms of all that you have previously said about Censi herself within the context of…

MF: The very male dominated world of art making.

RM: Yes.

MF: Well, it is very dominant in dance, particularly in the ballet world. I think that my real attraction to Censi was that she was unsung. I had never heard of her before. And so, I wanted to bring her into life. I wanted to look at her work, be inspired by it, and credit her on my program and have someone else think about her. Maybe they’ll go and research her too. I thought, what a great idea that this person had come up with some very interesting stuff and I wanted to bring that to life. I don’t know what she did in terms of the dance, how she put things together, but you can sort of surmise. If you look at the photographs, it’s like a sort of Muybridge type thing: shape, shape, shape. And so, that’s what we did! We went from shape to shape to shape. And once we got into the shape, I would have the dancer just hold it for a second. So it was: arrival, change, move into the next place, arrival, change, and move into the next place. I loved it.

Photograph by Molissa Fenley of a photograph of Giannina Censi from Italian Futurist Theatre, 1909-1944 by Gunter Berghaus.

RM: So, essentially…

MF: I know what you’re trying to get me to say [laughs]

RM: Your relationship with her brought her to new life.

MF: And she brought me a new life. I mean… that was the thing that was so great; it was new material for me, completely new material. I love that it fit into my oeuvre, certainly, it fit into my aesthetic, and yet it wasn’t from my aesthetic. So, I loved that. And I found that working… and the dancers, when I would show them the photos… we just all fell in love with her. Here’s this woman, what an interesting thing. It made you realize that in history you hear about the things that the critics want you to hear about. That history is just so difficult, in the sense that you have no idea what was going on in the entire gestalt of Futurism in this case. You know about the artists that were written about. But here was this obscure person that somebody finally, showed in this book, again I was just lucky to come across that book, it was on the top floor of the exhibition along with other books about Futurism but Censi wasn’t in any way a part of the art exhibition. She was just in this book. And she was the most interesting part of the exhibition for me.

RM: Extraordinary. Have you ever felt that same way as a dance artist in your own career?

MF: Well, I feel… I just turned 60 years old.

RM: Why do you use “old”?

MF: Well, just because that’s vernacular. I am 60 years of age. [laughs] So, in other words, I’ve been around a long time, I’ve been choreographing since 1975. I’ve had a dance company since 1977. And, there’s a part of me whom questions… How is it that I’m not further along as far as the consciousness of dance? For instance, the other day I saw a book about “American Dance” and my work, along with the work of Elizabeth Streb, was described in one paragraph! This book was a huge anthology and both of our careers seemed to be a mere footnote. To me that is simply irresponsible!

[pause]

RM: Let’s go back to…no… we’ll skip ahead now to Esperanto. Esperanto premiered…

MF: 1985.

RM: Where?

MF: In Tokyo.

RM: And its New York premiere?

MF: At the Joyce.

RM: Yes. Esperanto…

Esperanto, 1985. Photograph by Chris Callis. Molissa Fenley and Jill Diamond.

MF: Esperanto was commissioned by a producer in Japan named Shozo Tsurumoto and his organization, Tsurumoto Room. Esperanto was a work with original music by Ryuichi Sakamoto. The entire work is a full evening length work and what I brought to the Judson just recently was a revival of part one, which is 30 minutes long.

Esperanto (Revival), 2014. Photograph by Reiko Yanagi. Rebecca Chaleff and Christiana Axelsen.

RM: Yes, and could you describe at that moment, the economies that Molissa Fenley and Dancers was circulating in…

MF: The 80’s was a really great time for my company. We had a lot of sponsorship and we had commissions.

RM: For instance, I remember Cenotaph …

MF: Cenotaph was a commission by Jacobs Pillow.

RM: I also remember Geologic Moments was commissioned by BAM?

Geologic Moments, 1986. Photograph by Sandi Fellman. Silvia Martins, Molissa Fenley and Christopher Mattox.

MF: Yep. That’s right. Geologic Moments at BAM. Also at BAM, Hemispheres in 1983…

Molissa Fenley and Dancers, 1985. Photograph by Chris Callis.

Elizabeth Benjamin, Molissa Fenley, Silvia Martins, Scottie Mirviss, Jill Diamond.

RM: With settings by…

MF: Francesco Clemente.

RM: Please describe the media that you conceived with Francesco Clemente, what you call the setting…

MF: The visual element we called it…

RM: The visual element for Hemispheres.

MF: It was a series of ten drawings. There were four packages of ten drawings a piece. So, there are forty drawings all together and they’re in four packages. It’s a little package, it’s the size of maybe like a 5” by 7”… maybe it’s a little more square. And these were passed out to people as they entered the space, as the audience came in they were given this package.

RM: So, there was, of course, the optical, the visual and the tactile.

MF: Yes. Also there was a sense of intimacy because the visual element was actually in your hands as you watched the dance. So you would have ten, and say you came in with a friend, you came in with three friends, well, you would have package number one and the person next to you would have package number two and the next person package number three. So you would imagine, Oh, I have this in my packet, the sort of like commerce going on… I like that one my friend has. Or, I want to trade, realizing that not everyone had the same thing. I think for me the idea of Hemispheres was, of course, left brain/right brain. It was West Hemisphere versus East. It was North Hemisphere versus South. Left brain/right brain had a lot to do with the idea of the intuitive mind versus the more analytical mind and these drawings pertained to perhaps the intuitive mind. It would be one image—a line drawing, pen and ink drawing—that was printed. A visual hit of something and that would go to the receptivity aspect of the brain that has to do with taking in images. And does that image then correlate to anything that is flying around in your own mind? You look at art and there is often that sense of, I know that, or I understand it, or I don’t understand it.

RM: In Recognition.

MF: Right. So [laughs] Do you want me to talk about In Recognition?

RM: We’ll come back to In Recognition.

MF: I think the thing that is interesting is that you’re suggesting that these titles of mine actually pertain to states of mind. In Recognition does have to do with a sense of looking at something and having an Ah ha! moment, which is also a Eureka concept. You see something and it registers and your own memory then gets activated. Is this an image I know? Is this an image I don’t know? Does this image have a memory for me? Does it not? Is this a new image? Is this an image I have a history with? So, I think that that’s what’s going on in the audience prior to watching Hemispheres. Then the curtain opens and Hemispheres begins. It was choreographed with a lot of patterning; phrases that would take place in terms of pattern but then an expectation that had been set up would shift. It’s not a pattern dance, because a pattern dance, in my mind, is something that is consistently manifesting in the same way. “Same way” being a very inaccurate term because it’s never the same, it’s now and now and now. You know, it’s moving through time.

RM: And, moving through your own personal hemispheres.

MF: Right. So that metabolically you are shifting and you are changing.

RM: And the literal hemispheres in which you have…

MF: That you are in. As I choreographed the work I would think, well, this movement is from the Western Hemisphere, this is from my intuitive mind, this is from the North Hemisphere, this is from a place of winter.

RM: And also in your body, your body has literally traveled through hemispheres. Born in Nigeria…

MF: Born in America but moved very young to Nigeria.

RM: Raised in Las Vegas.

MF: No, no. Born in Las Vegas!

RM: Born in Las Vegas…

MF: [laughs] Born in Las Vegas, grew up in Ithaca, New York, until I was six.

RM: Born in Las Vegas, moved to Ithaca, New York.

MF: Then we moved to Ibadan…

RM: Ibadan, Nigeria.

MF: Then, I’m traveling all over the world with my parents. We’re going everywhere. And then I’m going to boarding school in Ibadan, then boarding school in Spain. And then coming back to the United States going to college and then I’m starting to tour and traveling all over the world.

RM: Yes. Now let’s get back to this universality of all of the hemispheres that you’ve been inspired by. Why Esperanto? Why a dead language? Why a utopic failure?

MF: Well, because then it wasn’t necessarily a utopic failure. 1985, I’ve forgotten the year that Esperanto was started, or tried and failed. I thought that it was kind of interesting that when it was thought of, it was all Latin languages. So, it doesn’t have non-Latin languages, it was not really a universal language. But in my mind it was a progressive thought. And, it was a progressive idea. Now we have binary language, which is universal—the 1s and the 0s, everybody understands that, computer language. But then it was this progressive idea. Is there some way that we could find a distillation of all these different languages? It was to find something that in essence anybody could speak in. Growing up in Nigeria what was interesting to me is that there are about 200 dialects of language in this country. There are the three main languages: Ebo, Hausa, and Yoruba. But within those there are all sorts of sub-accenting and sub, different, smaller languages. For one person of one language, to speak to another person of another language, they’re talking in English because Nigeria was a British colony. So, right there, their universal language was English.

RM: And, the moment of Esperanto, also reminds me of giving hope in the way that you give hope to Censi.

MF: Yeah! Absolutely. It brought life to the idea of an idyllic state. The ideal. The state of… What was I going to say? I lost my train of thought.

RM: And it was originally all female.

MF: Oh! What I wanted to say. Yes. I wanted to say that Esperanto was not only language between humans; it was language between animals. [laughs] Ryuichi Sakamoto, when we worked together, the way we worked together was that I made a scrapbook of images for the piece. There were images of penguins, there were images of Aboriginal art, and there were images… I wish I had it! I sent it. I’d love to have it back. Anyway, it was a scrapbook of ideas or things that I found interesting. And, it was really quite ingenious, I thought, the way that Ryuichi used these different images to come up with different sounds. For instance, there was a whole thing about dolphins that I sent him and he recorded something that literally sounded like you were talking under water.

RM: This reminds me very much, this notion of communication amongst species.

MF: Yes, absolutely.

RM: It reminds me very much of Floor Dances where you have…

The Floor Dances (Requiem for the Living), 2013. Photograph by Ian Douglas.

Molissa Fenley.

MF: Yes, embodied… Not necessarily did I think of myself as a bird encrusted in oil, I felt that I was nature itself defiled.

RM: Yes, I remember that you entered into an empathic and sacred space, in the post show discussion at New York Live Arts with Bill T. Jones. That you entered into a world, and these are quotes from my notes of that post show discussion, where you became in your words “cross species.” You said, “I am the other.” And there’s a rebirth and that ultimately it was “A landscape of love.”

MF: Yes, isn’t that interesting? A landscape of love. That idea is so progressive, an ideal.

RM: In a way, it seems as if these images, I remember when you were making Floor Dances, I remember the oil spill, I remember the images we were all looking at… and you, in your own words, created this landscape of love and entered into this otherworldliness, this empathic sacred space, that had no bounds of specie, had no hemispheric boundaries, a utopic ideal as Esperanto itself.

MF: Yes, absolutely. And a lot of the movement in Esperanto is very, very rhythmic and using a lot of the upper body in ways that to me is suggestive of other cultures.

RM: Suggestive? Why the word “suggestive?”

MF: I don’t take a Balinese mudra and copy it. I don’t want to study Balinese dance.

RM: But, you actually studied and experienced these dances.

MF: Well, from afar. I haven’t done them myself physically. So what I want to do is take the idea that I see and filter it and do something that is reminiscent. To me it’s my idea of what they’re doing without learning the actual thing. I want to take the actual shape, like the way the hand is angled. For instance, in Balinese dance the hand is used in a very extreme way. I don’t want to do that but I want to do something that is taking my physical self and doing something that is extreme. That’s angled, sculptural, could possibly have something… I think suggestive is the right word. I want to say that it’s a filter and it’s through my sensibility rather than wanting to do the actual dance itself. I want to know about the actual dance so that when I do something, and I have my hip out, say, I can acknowledge that’s kind of Indian, but it’s not really because I’m not Indian. It’s kind of Tibetan, well kind of, but I’m not Tibetan. I am doing something that is taking an empathic sense of what something is and filtering it through my particular physical self. My physical body really understands Tribhanga, the three bends… the head’s going this way, hips going this way, knee going that way. That all to me is…

RM: Almost discovering/uncovering a universal language like Esperanto.

MF: Yeah, I think so.

RM: And, why do you think the female bodies of the Esperanto original cast… Do you feel that the female bodies at that moment in time and space of Molissa Fenley and Dancers… Esperanto, Hemispheres, Cenotaph…

MF: Hemispheres, Esperanto, Cenotaph… they were all female.

Molissa Fenley and Dancers, 1985. Photograph by Chris Callis.

Molissa Fenley, Elizabeth Benjamin, Silvia Martins, Scottie Mirviss, Jill Diamond.

RM: Did you feel that these universalities, these archetypal Esperanto’s, are more legible through a female form?

MF: Not necessarily. I think that what I really liked was the idea that having grown up in Nigeria, the men danced with the men and the women danced with the women. There’s a tribal thing, and I really liked the idea of a kind of ritual taking place. To me, the ongoingness of Esperanto, from part one through two through three, it’s the same women going through this pretty long process: very physical, very demanding, huge movement through space as well as very delicate movement through space, huge shifts of dynamic range.

RM: Geologic shifts. Shifts in tectonic plates at geologic moments.

MF: Yes, all that too.

RM: Which also reminds me of the solo where “you approached the drop of a cliff…”

MF: In Nullarbor, yeah.

Nullarbor, 1993. Photograph by Tom Brazil. Molissa Fenley.

RM: The Nullarbor, is where? Australia?

MF: Yes. It’s the southern coast of Australia. It’s called the Nullarbor. It’s a plane that goes right to the edge and it’s a 200-foot drop. It’s limestone. And the Nullarbor [no trees] is a plane leading right up to it. But yeah, it’s just a drop off.

RM: Back to the Geologic Moments of Esperanto.

MF: [laughs]

RM: Let’s talk now about this notion…

MF: This is an aside. But I think it’s going to be very interesting to have this conversation be about these senses of progression, of idealism and utopia and moving forward and not getting bogged down in money matters. Because, money is not progressive, the work that I do is for all. It is not for one body over another.

RM: How, then, do you feel about the notion that what you’ve done is read as a political act?

MF: I think that’s perfectly great! See, for me, it is a political act. In the sense that I have chosen to go the route of my own life.

RM: Which brings me back to Redwood Park…

Redwood Park, Part 2, 2014. Photograph by Julie Lemberger. Christiana Axelsen and Evan Flood.

MF: Okay, with Censi…

RM: And this notion… I have a sense with you… as this kindred spirit with the early, what we call, the first generation of Modern Dance pioneers in many hemispheres. This notion of you not coming necessarily from a specific school, i.e. Molissa Fenley in blank company for x number of years, departs, starts own company. I feel like the work of your dance, the labor of your dance… It reminds me very much of the early pioneers, of course they were greatly influenced by each other, it was a Zeitgeist, there was a sense of communication, there was a cross-fertilization. But you, from the start, like an Isadora, like a Graham, like a Ruth St. Denis, really spent no significant time…

MF: In anybody else’s ideology or vocabulary.

RM: Yes, because we could look for example at Paul Taylor and we could see very clearly – principal male in the Graham Company. We see this very clearly with Merce Cunningham, in his own words “putting Graham’s torso on ballet’s legs.” And, of course making history, historiography. But very much like, say, a Miss Ruth, taking on these hemispheres, inventing her own school, her own training methodology.

MF: Which is part of it too, I’ve done that.

RM: I feel like if there is such a thing as a Modern Dance “tradition,” you’re coming from the tradition.

MF: I’m coming from the tradition that you made it up yourself. [laughs] You made it up yourself from watching and extracting the things that are interesting for the progression of this particular pursuit. So that means, if there’s an Aboriginal dance that’s interesting, then I want to know about it. I want to have access to it, so that it can influence what I do. It can be inside the brain as the vocabulary gets made.

RM: Yes, and this notion of the iconoclast. Which I personally associate with what we call this canon, whether its Eastern or Western, whatever the hemisphere is, we have these individuals that emerge and then become institutions. We see it with Kathak. We see it in all sorts of Eastern traditions. We see it in the Grand Compositions of the Tang Dynasty. These individuals emerge and become institutions. I personally feel you’re of this universal Esperanto.

MF: [laughs] Yes.

RM: Now, you talked about… Let’s go back to Esperanto at the Judson. All female originally and at the Judson we have men…

MF: Two men, two women.

RM: Why?

MF: Well, I’m extremely pragmatic. I work with who’s available to me.

RM: Now, let’s talk beyond pragmatism.

MF: I really liked these two men in Redwood Park and as I was putting together an evening at the Judson, I asked them can you come do your part at the Judson?

RM: That’s very pragmatic.

MF: Well, okay.

RM: Beyond pragmatism, beyond economies that you don’t want to talk about…

MF: [laughs]

RM: Beyond pragmatics.

MF: I like these two dancers, Evan [Flood] and Matthew [Roberts]. I like the way that they worked with Chris and Becky. I felt that they were able to do my movement in a way that was different from the women. I thought it was an interesting, new attack. Evan had a very clear attack and Matt did everything really in a smooth way. What I found interesting was that the four of them brought Esperanto into a very different place from where it had been originally. It is years and years later. It’s 20 years later from the original. The original was ’85 and this is 2015 practically. So, it’s an older dance.

RM: Almost 30 years.

MF: Yeah, and I felt that those four dancers danced it like it was made yesterday.

RM: Now that’s very interesting. To me, I felt like perhaps I was watching Separate Voices.

MF: Yeah, no, I could see that. For someone like you who knows my work really well, I can see that. I felt that it was a good gamble. [laughs] And that it was interesting for me, now this has to do with my being kind of incapacitated during this whole process, and it wasn’t until I got close to the Judson that I was able to do anything.

RM: Which, we know you experienced before in full sight, onstage at the Joyce.

[On January 24, 1995, opening night at New York’s Joyce Theater, Fenley collapsed to the floor, twenty minutes into the program’s first solo. The curtain was closed and the rest of the season was cancelled due to a serious knee injury.]

MF: Yeah, you know, it’s a dancer’s life. Once it was a dance injury and now this was a stupid, falling on the street, human being injury. But, injury it was and so I needed to be able to work.

RM: However, your body has been able to renew itself. You never thought you could do Floor Dances again.

MF: I didn’t, and then I finally realized I could. It was just a miracle to be able to bring that piece back. To be able to live that piece physically and mentally again for myself was so moving, I could barely stand it. I was just in heaven to be able to experience that piece again. Older now, years and years of experience, years and years of environmental horror taking place. To go back to something that was, in my mind, the first time that I was aware that the environment is really a big problem. We were just starting to wake up to it. Of course, it had been a problem for quite a while, but I personally was just starting to wake up to it.

RM: And your body was able to renew itself.

MF: Yeah, just the way that the earth renewed itself up there, in Alaska, with all the oil. Finally reseeded and…

RM: And of course, it’s timelier than ever because we have, perpetually, one environmental disaster after another, across hemispheres.

MF: Across hemispheres and it is becoming harder and harder than ever, probably, for the earth to recover from things like that because the climate now is such a mess.

RM: Now, let’s go back to Esperanto at the Judson. I also think that it is very interesting that you are the only choreographer who has ever set a work on the Bill T. Jones and Arnie Zane Dance Company and it was Esperanto. And, if I remember correctly it was specifically because of Bill T. and Arnie at that time?

Esperanto, 1993 with the Bill T. Jones / Arnie Zane Dance Company. Screen Shot of VHS video by Molissa Fenley. Molissa Fenley, Maya Shiffrin, Odile Reine-Adelaide, Heidi Latsky and Andrea Woods.

MF: No, Arthur.

RM: Excuse me, Arthur, at that time felt like the females of the company weren’t getting enough dancing? Could you describe how this came about?

MF: Yeah, I remember it very well. I was having dinner with Bill and I said, I was going to be 33, no, 35, and I wanted to give myself the present of reconstructing Esperanto. I was working as a soloist and I didn’t really want to go out and just audition a bunch of people. And, I was very close with both Odile and Heidi that were in the company and I thought, wow, why don’t I ask Bill if I can use his dancers! I was doing it at The Kitchen for my company, for my show, and then he decided to do it for his show at the Joyce. Originally it was Odile, Maya, Andrea, Heidi and me, [at The Kitchen], and at the Joyce, Arthur was supposed to dance my part. But, Arthur had a hard time learning the part. There wasn’t enough time to get it together; the counting was really hard for him. The counting was impossible! It just wasn’t going to work. So, I ended up dancing my part at the Joyce.

RM: That’s so interesting.

MF: Well, it goes to prove that a dancer is not like a machine that can do anything. An athlete who is a great runner is not necessarily a great swimmer. You train for something. And Arthur was brilliant in Bill’s work and in his own work, but it was really hard for him to do this particular work of mine.

RM: I can understand that. But, you said something super interesting I’d like to pick up on… this notion of the women and counting.

MF: Yes, it’s really mathematical. And you have to be able to do things, like…Say there are three measures of five. That’s fifteen counts. Someone is doing three measures of five and someone else is doing five measures of three. And then you end up at the same time. So, you start at the same time, then you go off and are in this paralleling thing. Fifteen counts being put together and accented in different ways. Five packages of three, versus three packages of five. That could be really hard for people who don’t know how to do that, or don’t have experience of doing that.

RM: Has it been your experience that male bodies have had…?

MF: You, you were a great counter!!

RM: I am a great counter.

MF: [laughs]

RM: Thanks to you.

MF: There are a lot of women who can’t do it either.

RM: Okay! I’m just curious about that.

MF: I don’t think it’s a female versus male thing.

RM: That’s interesting because you did say there’s a moment you felt like that, at that moment, with Esperanto, with the Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Dance Company, you did say, there was a moment where it seemed like the women were picking up the counting.

MF: Because I was presenting the women with me at The Kitchen, there wasn’t really time for Arthur to learn my part. I’m sure he could have done it with more time. He was really asked to be a fast study. It wasn’t fair.

RM: Okay, understood. This kind of work is not a fast study. So you haven’t experienced this notion that…

MF: Women and counting? No.

RM: Terrific.

MF: If I lead you to believe that, it’s wrong.

RM: I don’t know that you ever did. But, we have to look at the breadth of you career… you have spent much more time onstage with women and your own body, than with men inhabiting the same space and time. With Esperanto, did you feel that, I think this is pretty clear; you were speaking the language through your body…

MF: Definitely.

RM: In this progressive hope of communicating across hemispheres, across language barriers?

MF: I think that just as a dancer to get yourself to the point where you can do something like, Esperanto, is such a progressive thing for humanity. It’s just so great when someone spends an enormous amount of time doing something, training, so that they can do something well.

RM: Which reminds me very much of Energizer at the NYLA season, this notion that there is not at all a sense of exhaustion. There is a sense of the accelerated; you called it something like, accelerated meditation and a state.

Energizer (Revival), 2013. Photograph by Ian Douglas.

Peiling Kao, Christiana Axelsen, Cassandra Neville and Rebecca Chaleff.

MF: Yes, it’s definitely a meditative state. Because you’re working at such a degree of the mind, the body, everything is really paramount, it’s really extreme. And so, that’s going someplace. There’s some kind of transformative thing going on there.

RM: I remember particularly, in the pieces I learned and performed of yours, Geologic Moments, as your student at ADF [American Dance Festival] and Cenotaph that I performed as a solo at DTW [Dance Theatre Workshop]. I remember you rehearsing with me and telling me, because I had hit a wall, working so hard everyday at DIA [DIA Arts Foundation] while you were on tour, and you told me that if I just kept going, if I kept progressing, if I kept pushing, not only would I break through that wall and transcend what I had perceived as a limitation of my body…“I can’t get past minute 11. Period. Should we just call this whole fucking thing off?” And you said keep working progressively. You will push through that perception.

MF: You will find a well of action, you will find of reservoir of energy that you never even knew was there.

RM: Yes. And I did.

MF: It’s really true. The same thing happened in Esperanto. The two dancers, Chris and Becky, who had been in Energizer, were prepared for something like Esperanto. That was just excellent preparation for them.

RM: Yes.

MF: Matt and Evan were new to this kind of extreme thing and they’d be like AARRRGGHHH. I remember once Evan saying “I love Redwood Park!” and I said, “I want you to love Esperanto just like that.” [laughs] And so, we worked and we worked, and we worked, and we had one night to perform it. And, it was the sort of thing that you could have done it for a week after that, you know? Because you’re now at this high and you think “Where’s it going to go?” It just gets better and better. That’s what he finally realized. I think it was the day before, it was like, “WOW! I have really gotten through. I am now at this other state.”

RM: Yes, and the same thing, of course, with State of Darkness.

MF: Oh, yeah! Working with Peter Boal on that, working with Jonathon Porretta. Yeah. [laughs]

State of Darkness, 1988. Photograph by Jack Mitchell.

RM: This notion that just when you think there is no way that she is going to finish, it must be coming to a decrescendo, you actually accelerate for the last, what would you say, several minutes of the score?

MF: Seven minutes of the score.

RM: For the last seven minutes of the score.

MF: Yeah.

RM: Now going back to Esperanto, what was it like, for you, to see your archive coming to life?

MF: Pleasure, just total pleasure. This stuff just sits in a video box. That’s what’s so terrible about it. It just sits in a box and no one gets to see it.

RM: Well, if memory serves me, I remember that you actually said something about this notion that your memory and your body were more reliable, at certain moments, than your note taking and other forms of media that you were using for Energizer at NYLA.

MF: Yeah, that’s because both of those dances, both Energizer and Esperanto, I physically danced, myself, many, many times. So there’s an imprint of trace there. Of one action into another, what follows what. So, in reconstructing it, you’re looking at the video and you’re going this this this this this… And suddenly you’ll go back into the space and do this this this this and I’ll say Oh! This follows! Because, it’s just like it’s right there. The door opens, and Oh yeah that was afterwards. But that’s not every time.

RM: But it was definitely a part of your process when you revisited Energizer at NYLA how many years after the premiere?

MF: Oh about 35. I mean, 1980, and this was 2013. 33 years.

RM: Yes, yes. So, it stayed with you, some parts of it.

MF: Also, I have a very particular vocabulary. If there’s something like that, there will be, I just know choreographically what I might do.

RM: Yes, I understand that. So it’s almost… sure, your body becomes an archive that is, in a lot of ways… What we think of as a traditional archive, for instance, I’m thinking now at Mills College, it’s housed in the Mills College special collections, the Molissa Fenley archive. So, that we would consider a more traditional archive… shall we say? Or, a more traditional idea of an archive? I also remember, back to Energizer, this notion, when you and Bill T. Jones were in conversation post show; you were quite defiant that you’re not minimalist. You said, I think I can quote, that “it’s not minimalist at all.” And, that one needs to realize its complexity. The choreography is intact, and that what is different, is the people doing it. But, let’s go back to the acceleration, this trance meditation. This pushing past, this energy expenditure, the increase that heightens as the dance continues, that does not fatigue you.

MF: The same thing with Esperanto. The last five minutes, all of a sudden… it’s like chechechechechecheche…you know it just goes really fast. For me, when I remember getting to that point it was ecstasy. [laughs] Ecstasy!!

RM: An ecstatic state.

MF: Completely.

RM: Now, back to Esperanto at the Judson. Seeing, feeling, all the various ways that you reconstructed how much of the original?

MF: First act which is 30 minutes.

RM: Yes. What did you see, hear, experience while watching? Esperanto being danced in costumes that were not the original costumes by Jean Paul Gaultier?

MF: They’re lost. Terrible.

RM: What did it feel like?

MF: I felt very happy. I felt very accomplished. I felt like it was a really great thing to revive the work for this new audience. I think that my audience had not seen a piece like that. Well, there was Energizer but, again, that was the first time that something like that was brought back. My early work, I feel, came and went very quickly. That whole period between 1980 through 1990, that’s ten years worth of work and there’s a huge amount of it. And I am now, really methodically, bringing dances back because I think that… personally, I want to have them in my world again. But I also think that it’s good for people to see it, because it’s a part of our culture.

RM: Would you have liked more people to see it, for example, in comparison to its premiere?

MF: I’m not sure what you mean.

RM: Let’s talk about its American premiere. Let’s go to the North American hemisphere. I’m sorry, the hemisphere that encompasses many Americas.

MF: Western hemisphere, yeah. Okay.

RM: That New York premiere was at the Joyce.

MF: And it was also on the same program as Cenotaph.

RM: Yes, let’s stick with, before we get to you and Cenotaph. I want to stick with this notion of wanting people to see it. And, in comparison to its premiere in this hemisphere, at the Joyce Theatre, which seats x number of people, with how many performances?

MF: How many performances? Probably a week’s worth—six or seven. And then it toured quite a bit.

RM: Let’s stick right with that premiere. Would Molissa Fenley have, perhaps, preferred that…

MF: It was at the Joyce this time? That’s a larger hall.

RM: Not necessarily at the Joyce. That more people would have experienced it than did, when you gave us the gift of one evening, for those of us fortunate enough to have been there.

MF: Well, it was very nice to do for one evening, and it would have been very nice to do more. I’m very happy to have brought it back into life, because it wouldn’t be so hard to bring it back. If I had a gig, I could get those dancers and put it together.

RM: And there’s the pragmatist who is circulating, practically, in an economy…

MF: Well, I don’t know if that’s pragmatism, that’s just a blatant wish. I wish it had more work. I wish it had more jobs. Yeah. I would love to show my work more. I just don’t have the avenue for it. I find that I have to manufacture them myself. NYLA was great, because they invited me.

RM: For their Replay Series. Yes. In Recognition, with your longtime collaborator Philip Glass, I’m almost certain I recall you wanting to wear Arnie’s ashes.

MF: Oh wow. I’d forgotten that. That could well be.

[phone rings]

RM: In Recognition.

MF: Did you see it at Serious Fun? That was the festival that was at Lincoln Center. Alice Tully Hall. And I wore white as a kind of mourning. But, I don’t remember that about the ashes, but that sounds right to me. That sounds like something I would have said. Yes!! This is really ringing a bell. Do you remember my saying that? Otherwise you wouldn’t have come up with it.

RM: Yes, I remember. And if I recall, In Recognition, which brings us back to another hemisphere, Sakamoto brings us back to Japan, is actually from the Mishima film score.

MF: Yeah, that brings us back to the whole seppuku thing.

RM: And do we remember the actual track of the Mishima score?

MF: No. I’d have to look it up. I don’t have it on my tongue.

RM: I have the CD, we’ll check.

MF: Okay, I know I’ll recognize it.

RM: Now, how long is that solo? Is it the length of that piece of music?

MF: I think it’s 11 maybe, 9… it’s short.

RM: Let’s talk about that moment, In Recognition. The year?

MF: That was 1987 going into ’88. Separate Voices was 1987, so, and that was the piece with Doug Johnson and Robert Mason and Scottie and Silvia and me at the Joyce.

Separate Voices, 1987. Photograph by Sandi Fellman. Molissa Fenley.

RM: Yes, but let’s go right to… Arnie Zane passes?

MF: Well, no, he saw the piece.

RM: He saw the piece. Who is the piece In Recognition of?

MF: Him!

RM: Why?

MF: I loved Arnie Zane. Arnie and I were very close. We had been on tour together, way back during The Kitchen tour in 1980. It was Bill T. Jones and Arnie Zane dancing together and Lynne Allard and I, we were dancing Energizer as a duet. And, half the time Bill was not there and I would room with Arnie. We roomed together several times and we were quite close. I’d always felt that I was kind of in his family. And, so I felt like I wanted to make something for him, while he was still alive, and dance it for him as a thank you. Thank you for being my friend. Also, it was a kind of cathartic thing. We were all just a mess because people were dying left and right. All of our friends, lots of our friends… it was a destructive period. Because it was so clandestine still and the culture was so weird with AIDS back then. I wanted to make something that Arnie got to experience. And, I remember, I danced it for him at the DIA upstairs. He was sitting there and afterwards I came and sat on his lap and gave him a big hug. And he said, “it’s just so weird to see something called In Recognition because I’m not dead yet.” And I said, “I know. It’s in recognition of our friendship.” It was in recognition of my friendship with him, but also in recognition of him as an artist, and as a person, who had been, we could talk art together, it had always been…

RM: Another landscape of love.

MF: Yeah. Absolutely.

RM: And let’s conclude with your own Cenotaph.

MF: Cenotaph was, I don’t even know what Cenotaph was. That was an odd piece. The music was by Jamaaladeen Tacuma. I didn’t get the score until practically the week before we went on stage. So it was made all to just counts. It was really intense counting. It was like, five six five six…

RM: Why the title?

MF: I don’t know. I’ll have to think about that. It’s in recognition to the dead, but it’s a monument to the dead and they aren’t buried underneath it. So, it’s a monument idea, monument of the past. So, a monument of tradition. [Cries] I don’t know!

RM: And what…

MF: What am I monumentalizing?

RM: In Cenotaph. In the ballet. In the work.

MF: Pure movement, complexity, love. It was kind of a new language, a new physical language.

RM: Cenotaph is a memorialization. It’s a monument of memory and of the dead.

MF: Yeah. But it was in 1985. I’m sure that it pertains to many things. I can’t actually say that it’s one thing or another. I think it was just a sense of remembering things that have taken place. Sort of like a Proustian thing—time of remembrance past.

RM: Could you elaborate on the Proustian remembrance past? The sense of that:

MF: Here I am at a certain time in my life. Things were moving in a different way at that time for me. My company was… I could tell that my company dancers weren’t all that happy. I wasn’t all that happy. I had a very unhappy personal life. I don’t know.

RM: The persistence of some kind of memory.

MF: Yeah.

RM: And let’s conclude with going back to the NYLA season. In that post-show talk, I remember your saying something to the effect…the first reading might be feminine energy. But, you said you encompass both.

MF: A male and a female. As a human energy.

RM: And that it is ultimately a humanist worldview.

MF: Yes.

RM: And that said, what does the Futurist, Molissa Fenley, envisage her own Cenotaph to be?

MF: Whoa. I don’t know.

RM: Let’s stop there.

MF: [laughs]

RM: 90 minutes, I told you. And this could go on and on and on…

MF: and on…