I make dances with objects and sometimes there are no objects and I think about the body going in and out of objecthood. Alexander Calder made objects that dance, independent of dancers. I didn’t really know much about him until the exhibition Calder: HyperMobility at the Whitney Museum where I have had the opportunity to activate his sculptures. As a dancer, the experience has been an inversion of my process.

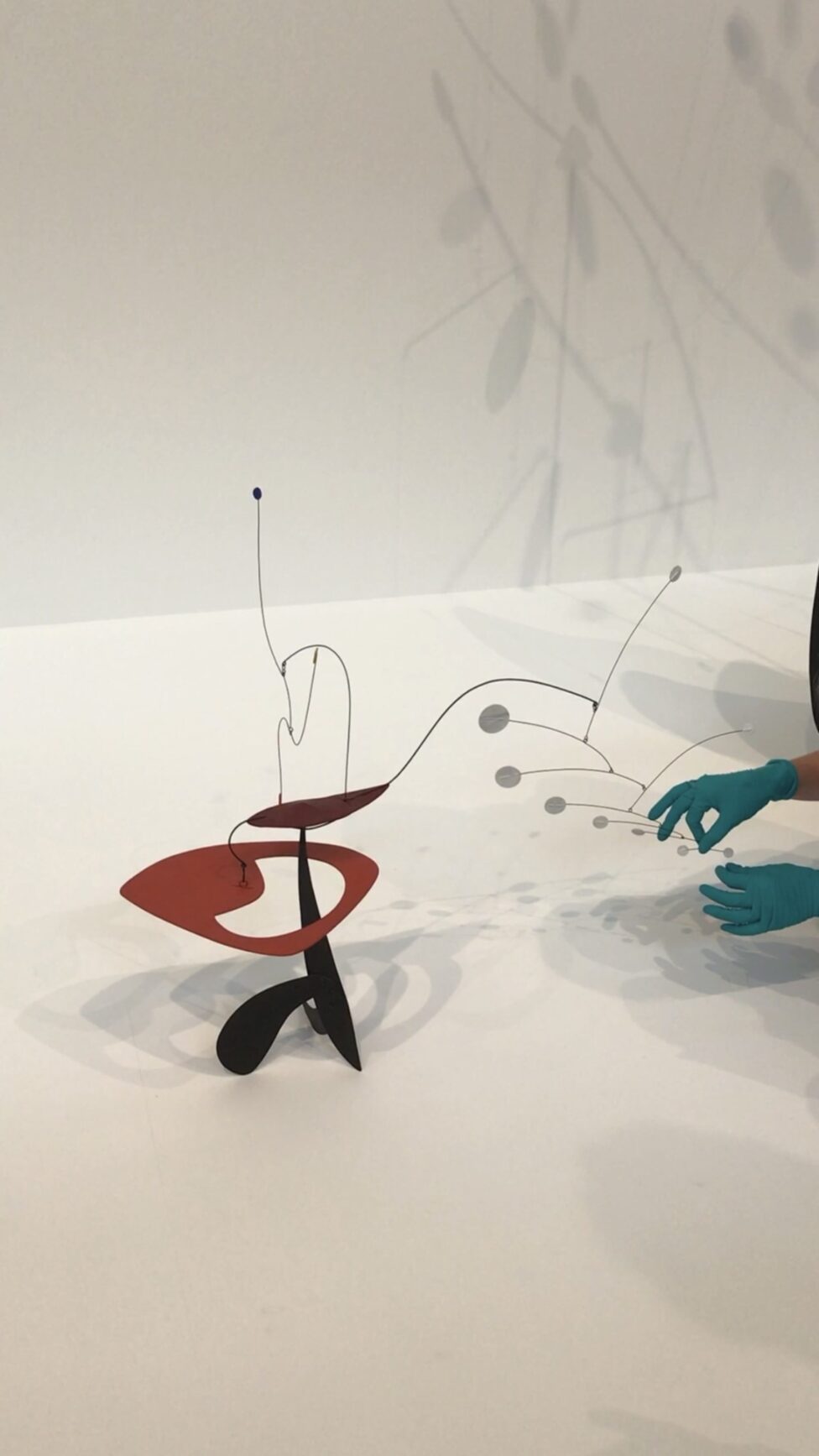

For the last four months, my job has been to move four sculptures every hour on the hour in front of a large crowd of museumgoers. There are very specific points on the sculptures that are to be touched. Alexander S.C. Rower, Calder’s grandson and president of the Calder Foundation, taught the Whitney art handling staff how to move the sculptures through tutorials, kinesthetic transmission. This is also how dance is passed down from generation to generation, one body teaching another body the movements.

The mobiles, standing mobiles, and motorized sculptures in the exhibition are positioned on a platform that is like a stage around the perimeter of the gallery. All of my movements to approach the sculptures have to be specific and choreographed. I have to open my body to the audience the proscenium way. I think about the line of my body in relationship to the form of the sculpture. I consider my hand as an ornament that must complement the sculpture.

When I activate the sculptures I like to stay still and watch for a very long time until the movements slow down at the very end. If I walk away immediately after touching the sculpture, the audience thinks the activation is over. The stillness of my body helps viewers to stay focused on the movement of the sculptures.

The works have a way of forcing you to be present in the moment. But they can also transport you. Touching Autumn Leaves, Red Post (1941) is like climbing a tree and shaking the branches to watch the leaves fall. Aspen (1948) is to be touched with an up and down and circular push simultaneously. The plate and the rods with the small white discs at their tops bob around as if they were on a gelatinous sea. I like this piece for its liveliness and elegance; it gave me the feeling of being on my family’s fishing boat on the Pacific Ocean.

Once I begin to think of each sculpture as having its own dance score, I become more engaged with each activation I perform. For example, Red Sticks (c. 1943), is a mobile with six red wooden dowels and two wooden elements at the bottom. The Calder Foundation wrote the following description on their Instagram account: “The motion of the titular elements is variable. They create X’s in the air passing each other by and trick the eye with foreshortening, such that the piece looks nearly unrecognizable from one moment to the next. Although the wooden dowels seemingly move around a central axis, the strings that hold them together are subtly staggered, further contributing to the constantly expanding and contracting wingspan of the work”.

To properly activate Red Sticks, you stand directly underneath it and push the third dowel from the top in a ¼ circle with a long wooden stick that has volara at the tip. This moves the third dowel, which then triggers the rest of them to move in concert with one another. They create X’s and the wooden elements sway back and forth.

© 2017 Calder Foundation, New York / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

As a choreographer I read Red Sticks as a dance score with a composition of six dancers in red costumes; the figures stand in a line on the stage, then the third dancer in line turns and makes contact with the closest dancer in proximity and they create an X with the passing of their bodies. This has a domino effect up and down the line- it happens in succession, but then by chance, depending on the weight shift of their bodies. The second and fourth dancer could be synchronized at the same time as the first and third are moving in opposing directions.

I have activated this Red Sticks many times over the course of the exhibition. The score started out the same but there were always interesting new variations to the order. The sculpture never stops moving completely. It makes fast, large circles for a few minutes and then slows down to very subtle movements that are more dispersed. In a minimalist dance, the smallest movements are magnified and stillness may be the only movement. Stillness is my favorite move.