One year ago in January, I took Jeanine Durning’s workshop, What we do when we do the thing we do before we know what we are doing. We met 3:30-6pm for five days, notebooks in hand. We’d start in a circle and sometimes end in one. The workshop began on a Monday and ended on a Friday. The Monday was MLK, Jr. Day. The Friday was the Presidential Inauguration of Donald Trump. These “holidays” created margins for our practice (whether or not we desired this).

Through Jeanine’s nonstopping practice, we were out-dancing our own logics and moving quicker than we could think. We were finding new availability, testing preconceived boundaries, or at least going through the motions. It became clear to me that the improvisational practice we produced together valued NOT KNOWING WHAT’S GOING TO HAPPEN NEXT and SURPRISING YOURSELF.

I’m sitting in a circle, burning up with a question. I’m heartsick and bleary eyed from marching to Trump Tower the night before and the one before that. I’m feeling meaningless inside cyclical anxiety. I’m seeing a future that feels equally unpredictable and entirely known. This workshop is framed by the week that held it. Monday for Martin, Friday for Donald. Dancing for what?

I ask something like: the nonstopping that we have been cultivating seems to prize moments of not-knowing and assumes that getting yourself lost through your own patterns is a good thing. I’m feeling a sincere clash between this common improvisational desire to surprise myself with something new or something different and a deep opposition to fetishizing not-knowing. Not-knowing seems to be very valuable in dancing and very terrifying in our new (and old) American political world.

With Donald Trump’s election, I feel a constant sense of not-knowing and this produces fear and dread. How can we say not-knowing is a good thing? Why do we chase these moments inside of dance and hold them up as pliable or useful or generative when, in other contexts, they are deadening or even deadly?

In truth, I don’t remember the response I got. Something about the pursuit (I think). I had inadvertently exerted all of my extroversion in the question. But I still want to know an answer. I’m still searching for an answer, and with it, a better question.

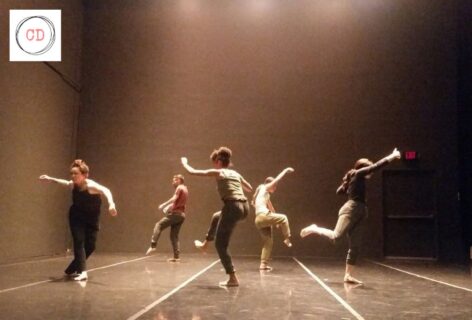

Image by Londs Reuter

I’ve continued asking fellow artists about not-knowing and surprising yourself. Some responses I’ve liked:

- Surprising yourself creates new neural pathways. For better or worse, these experiences contribute to human growth and development.

- Nothing Donald Trump does is actually surprising. I’m creating a false comparison.

- I’m creating a false comparison because Donald Trump’s material and my material as a dancer are in no way comparable.

- All experiences are new experiences, unless we exist only in our patterns. The opposite of allowing sensory experience is not allowing sensory experience, or going on “auto-pilot”—I don’t want to live on autopilot.

- We never really know what’s going to happen next and a dance practice can build our capacity to tune into and out of this awareness.

- We have enough dance techniques that, though they may have at one time included incertitude, are now completely Known (the steps, the body, the style). Would you seriously advocate against not-knowing when the alternate means recreating only what we already know?

And then I went back to Jeanine, who remembered this question. She recalled the full stop the question produced and her response to it. Jeanine acknowledged that not-knowing is indeed material to nonstopping. It is elemental to nonstopping. Because the material is not known, a dancer can have a “self observational and self reflexive relationship to thought, action, intention, relation, etc.” An aim of Jeanine’s practice is to sharpen attention and heighten adaptability. Predetermined materials would undermine such a pursuit.

While I’m still not convinced that NOT KNOWING WHAT’S GOING TO HAPPEN NEXT and SURPRISING YOURSELF are good things, I no longer see them in opposition to our political reality. I now see them as a tool for social action. Nonstopping can facilitate a critically-needed perspective. Jeanine explained to me how a practice of nonstopping allows a dancer to heighten her reactivity to a momentary shift. As American culture shifts and unearths some of its ugliest truths, we can heighten our ability to name evil when we see it and act against injustice when we see that, too.

While nonstopping relies on not-knowing, the main work of the practice rests in the dancer’s reaction. Nonstopping allows a dancer to move beyond materials and their individual value(s) and instead question her relation to them. In a political moment that is forcing individuals to question their relationship to systems of power, a nonstopping practice can heighten a person’s capacity to witness bullshit, understand that they are implicated in its formation, and act accordingly. Nonstopping demands that we see ourselves as creators in the world around us, whatever that world may be—as fleeting as that world may be—or in the case of Donald Trump, remain.

Photo by Londs Reuter