Conversation between Peggy Shaw and Lois Weaver where they take on the names, “The General” and “The President”.

The President: So, a while ago, I think it must have been 1992 or 1993, we were working on Lesbians Who Kill and as a part of that we did an interview for Movement Research and we took the characters of May and June that we used in that show and we interviewed each other and we called the interview May Interviews June. Ok, at the moment we’re working on a piece that’s based on Dr. Strangelove and you and I take on the characters, or we take on the archetypes of the characters of a President and a General and of course it’s a satirical look at that, but a humorous look at that. But it’s definitely a kind of position that we both take in that performance. So why don’t we give this a go and let’s call it the President Interviews the General.

The General: Ok.

The President: The first thing I thought I would ask which is kind of an immediate flip is to ask you what kind of question do you think the General would ask the President.

The General: How come he hasn’t fired me yet?

The President: And why in the context of this performance or even in this global context would you expect to be fired?

The General: Because currently our country is run by someone who fires everybody every day. Or they quit. So I just realized when you asked me that question that was the first thing that came to my mind, since I’m going to answer on impulse.

The President: Right so that your character is such that, your character actually operates on impulse doesn’t she?

The General: Yes that’s true. Someone was asking me yesterday if, they were very confused about how do I do the show if I have no memory? And I said I didn’t know really. *laughs* What show? I said what show? I guess I could get fired for having no memory in theater.

The President: You could get fired in theater for having no memory.

The General: Our company just enhances the show. It just adds another layer it means we have to figure out how I can perform without a memory?

The President: And how do we live in the world without a memory as we get older? To what extent does our memory mean anything, do our memories mean anything? Is it all that important if we’re able to live? This is what I’ve been thinking about, if we’re really truly able to live day to day and in the moment. I think it’s a waste of energy as we age to worry about the things we’re losing such as aspects of memory or memories. And I think for me, the need is to concentrate actually on what’s happening in the moment on a day-to-day basis.

The General: I learned today in cleaning my apartment, I remembered that when I moved to this new apartment because I had a stroke that I was trying to keep the philosophy that Deborah Miller had when her dad moved in with her which is to restrict him to only one wall of memories and then everything else in the apartment would be new. So today, I removed all my paintings from the wall, I threw away things that I thought had some meaning at one time, but I don’t remember what. So it’s kind of like the reverse of New York City. In New York City they remove a building and I can’t remember where I am, but in my apartment when I remove a painting or picture I stay in the present because I don’t have to worry about the memory.

The President: We’ll talk a little more about age further on, maybe in the conversation. Talking about the present, let’s give a better introduction of what the piece Unexploited Ordinances is based on and why we’re talking about the General and the President. It is based on a present moment and how would you describe that present moment?

The General: Well even though this country won’t say it out loud we’ve had a coup of our government and several years ago when Lois and I became obsessed with Dr. Strangelove and working with elder people, because we’re elders, we didn’t realize that we would be, that we were sensing what was going to happen. Right now we’re trying to all live through an anarchy that’s happened. Not a good anarchy. The government has been taken away and services are being taken away and money is being taken away from all the millions of people in North America. So through our performance we’re trying to talk about what exactly is happening and it changes every day.

The President: When we started, you’re right, we started by becoming obsessed with Dr. Strangelove. That’s one of our ways of working, we become obsessed accidentally sometimes with something and end up figuring out a way to put it into the work. So we did, but we were looking at a sense of urgency, probably in terms of time, particularly as it relates to age. We’re getting older, we don’t have much time, time is running out, have we fulfilled our potential, will we fulfill our potential. If we look at our potential, is that a dangerous thing or a resourceful thing? We thought “Well, Dr. Strangelove in its use of the doomsday construct might be useful in that way,” but now it feels terrifyingly relevant because, as opposed to it being something that became a constructional metaphor it has become a terrible possibility or even a fear that we’re really, really living with.

The General: Well we used to call it, what was it called? Collective Consciousness.

The President: Yeah, that’s what we’d call it.

The General: And suddenly we would find ourselves all thinking about the same thing. We have sometimes even made a show using the same scene, the same props, in the same scene that someone 30 years before had used without us knowing it. It’s a cosmic consciousness of some kind.

The President: Sometimes I used to think that there is this river of material like an underground water table that’s running under us and that when you’re drilling down, which is part of what you do when you’re making a show, you drill down you pick up that material, and it might be some material that someone else, as you said, has used twenty years ago, or five years ago, or five minutes ago and you pull that up. So, I never have really believed that things are truly original. That we, like matter, get recycled into other matter. That’s how performance material gets recycled into other ideas, I sort of think that.

The General: Well, I laugh when I see people accusing movies of stealing their ideas because there’s so many millions of people in the world and at one time or another we all have the same ideas and whether someone developed one or not. I wonder if even the exact tune of a song can be thought of by somebody else. That’s what cosmic consciousness is to me, there are no original thoughts.

The President: And one of the things I was interested in in looking back at this conversation that we had that many years ago and reflecting forward, one of things that’s different now is that everything is so accessible all the time, all the information, all the films that were ever made, all the music that was ever written, all of that’s constantly in front of us in a digital stream and for that reason it’s very hard to distinguish between what we perceive from the outside and what we invent from the inside.

The General: I also think that from my own experience and, if I can speak for you also, is that when you’re under the radar so to speak, when you’re on the fringe, there have been many millions of lesbians and people of color in the past that have created things and they were never published as music or as a play and so I think, I don’t agree that there’s all the music that’s ever been written you can find on the web.

The President: No, no.

The General: There’s always been alternative groups making beautiful work, but it’s just never been published.

The President: Right.

The General: I wonder how much the web influences our cosmic world because, say if you weren’t on it for five years, say you decided not to be online for five years, then I wonder if you would create something also of cosmic consciousness, perhaps with someone else who’s on the web, I don’t really know. It’s a tool we use rather than thrift stores or old recordings that we find. It is a tool, but sometimes it’s kind of boring.

The President: We’re bombarded. It’s almost impossible to escape and so we might hear things without intentionally listening, they come into our consciousness, and so I think that possibility is far more prevalent than it would have been back in 1993 when we were working on Lesbians Who Kill as May and June.

The General: Probably a lot of the most original stuff on the web is stuff that was made in the 20’s and 30’s that people have downloaded and put on the web. Like last night, I don’t know how this happened, I went to some dark cartoon web past that had horrifying racist cartoons and combined with beautiful jazz music I don’t know where I was, but I went deeper and deeper and found these horrifying cartoons that were made in like the 20’s by a guy, it begins with ‘L’, I forget his name. I don’t know if they had permission but they were put to the tune of Louis Armstrong singing behind the video, behind these horrifying images that were more dangerous than I’d ever even imagined.

The President: Wow.

The General: I just wonder who got the permission to do that. There’s one of Louis Armstrong’s band singing “I’ll Be Glad When You’re Dead You Rascal” to Betty Boop. I mean it’s just, anyways.

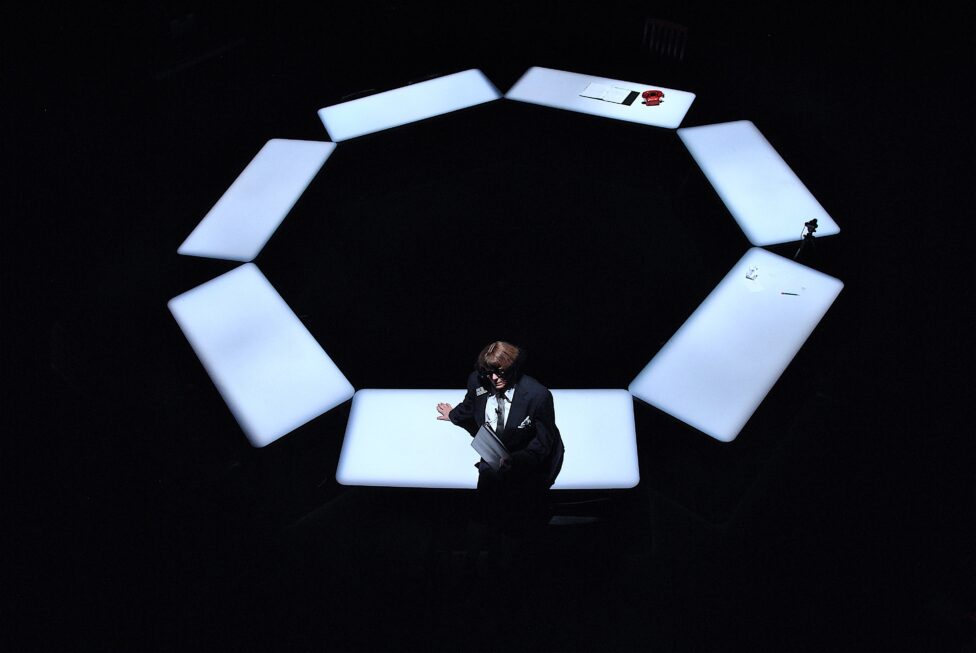

Photo: Peggy Shaw (The President) in UXO, 2018. Photo by: Matt Delbridge

The President: Actually that makes me think of the next question I wanted to ask in relation to again, looking backward to Lesbians Who Kill, and into the current present and maybe into the future. One of the things about Lesbians Who Kill is that it’s centered around the story of lesbian serial killer Aileen Wuornos and it wasn’t so much a biopic about her but it was a way for us to investigate ideas about violence against women, and our relation to that, and our potential violence against men in retaliation to that kind of patriarchal setup.

The General: In the beginning of Lesbians Who Kill Deb wanted to investigate, are we guilty because we think about killing men?

The President: We talk about that in the old interview, a bit like: is thinking it making it so, or does it make you guilty? That’s rooted in our sense of, in 1993, about what was women’s status in the world. But the question I was going to ask is, what kind of misogyny could bring about a kind of violence that we were experiencing or noticing then? I was just going to ask you do you think that has changed?

The General: Oh yes, absolutely. I mean misogyny is worse now. We were playing around with guns and pistols. We had guns. I don’t think we would choose to do that now. I think that guns have been taken over by old white men now and shoot ‘em up movies, and I think they’re much more consequential now. In the 90’s in the 80’s all our friends, women friends, were talking about taking shooting lessons and getting guns and now nobody wants anything to do with it.

The President: Well that’s a relation to violence. It sounds like that there’s much more proliferation of violence in general. We’re surrounded by the potential for violence. From thinking about Syria to all the way back to thinking about the Florida school shoot, to even thinking about the potential for someone to get shot on the street or police violence. I think we’re much more surrounded by it. I’m wondering, to go back to my original question, where do you think misogyny sits inside of that? Do you think we’re more misogynist than we were in the 90’s? I’m not sure.

The General: Well by ‘we’ I assume you mean our culture, not us?

The President: Yeah, not us.

The General: It is more misogynist because even though on the outside it looks like women have jobs now, whatever, they rise up in companies to a certain point, but not all the way. And a lot of them are quitting because it’s such a horrible way to live, around all those stupid old men, and the young ones. I feel like my own misogyny has changed. I think I’ve gotten much more enlightened about misogyny. It used to seem much simpler to me in that when you sing that song “Boogeyman” it’s very simple you just go out and you kill the perpetrator but now it feels so deeply embedded in our culture that I feel we’ve had to really stretch our brains to go down there and find out what is misogyny? It’s not a simple thing.

The President: No, and I think that’s really represented in all the things that we experienced around Hillary Clinton running for President. That level and those layers of misogyny were massive and hard to name you know, in various ways, and hard to point at. It’s always been hard to identify and hard to point at, but it felt so much more systemic and ominous.

The General: Now it does

The President: Yeah, now it does.

The General: The… I just forgot what I was going to say.

The President: That’s okay it might come back.

The General: Wait, one second, one second… Humor. Our humor has changed. What people found funny then was not the same as what they find funny now. Although sometimes I feel like when we use old jokes from the 70’s and 80’s and 90’s, people laugh harder now than they did then, in a weird way. They find them funnier. Like the word feminism. The same thing has happened to the word liberal that happened with the word feminism. They destroy it and undermine it and label it and keep it. I mean I heard a rant today by a white republican guy who was talking about “The Left runs all the universities and all the newspapers,” no he said the liberals run all the colleges! So bizarre! Well yeah, you know you’re not going to be running a college because you don’t know anything. *laughs* The anti-intellectualism that Jill Dun was warning us about ten years ago seems to have been like a flu, like the Lyme Disease of the mind.

The President: And also, if you look back to the 90’s when we were working on Lesbians Who Kill and you looked at the words like lesbian and the words like feminist or the words like serial killer, or any of those categories that we were working in for that piece. One of the things that we were looking at for that piece was certain kinds of complicity. How might we be complicit for this woman serial killer who killed 8 men because she had been a sex worker and had been abused. How might we feel like, we might have done the same thing in the same position? And there were also different kinds of complicity with working class women, that’s a position we took for these characters May and June and non-academic feminism, an experiential feminism, these were all things we were looking at and like you said, looking at with humor. And I think that would be more complicated now, don’t you think?

The General: What words? The points, the words would be different now. Like instead of serial killer it would be school shooter? What the media does is they take words and they disseminate them and there’s no subtlety to the public use of these words.

The President: But it’s not just the media. You’re talking about what the Right is doing to the Left in terms of demonizing the word ‘liberal’. I feel like the Left is doing the same thing to the Left in the ways that it’s demonizing words like ‘feminist’ and ‘lesbian’, you know what I’m trying to get at?

The General: Are you talking about gender politics?

The President: Yeah, like the language police. Thinking about those terms in 1990 and thinking about those terms now and how we might play them in these two different kinds of performances feels very different. It feels like we don’t have the same broad strokes in terms of the different ways we might be complicit with loads of other different factions of the population and yet at the same time I think we are all yearning for what was called intersectionalism something, where we look at the ways in which we have all these different kinds of oppressions within each individual and within each group and it’s difficult to have this broad humor that we were playing around with in Lesbians Who Kill.

The General: ‘Cuz we were broad.

The President: Yeah, cuz we were broad. And even in the title. I mean, we often said “Lesbians Who Kill, we don’t even have to do the show!” It’s was the title itself.

The General: Amy was telling me this morning she went with her sister to see that Peter Hujar show at Morgan Library and there was a woman, teaching people about the photographs and the time, and they were all young, and she came upon different people like “now you may think this is a woman, but this is a transgender woman, she’s still a woman, but she’s called a transgender woman.” And she was educating these kids. Isn’t that wild, I couldn’t believe it? She was like a New York sixty-year-old teacher with her students. It’s so cool!

The President: That’s really cool. That’s amazing. The names are different, the terms are different but do you think our ideas are different now from what they were in the 90’s? Again, thinking about approaching Unexploded Ordinances, what are the different ideas or different ways of looking at ideas now than when we approached Lesbians Who Kill in the 90s. Anything come to mind?

The General: I don’t know. I mean I was wondering about that this morning when thinking about these questions. I was wondering, “Do we work differently now than we did in the 90’s?” I think well one thing is that we decided, because we could, to take longer making the show instead of getting it up in a month and performing it for a year to make it. In this show we decided to make it and to take a long time making it. But I think our methods are almost identical, maybe I’m wrong. I don’t know. I have to think about that.

The President: A couple of things come to my mind. The first thing that comes to my mind is that what we have always done is use an inspiration like the Aileen Wuornos story to in some ways tell our own story. And so we begin, we don’t tell her story, we tell our own story within that concept and we do that by cycling through different kinds of popular culture references. So that’s how we did that. Now you’re right we are still doing that, we’re telling our own story through this idea of Dr. Strangelove and this idea of an Unexploded Ordinance, and I might come back to that in a minute as well, and these popular culture references, but in a way I feel like we’ve turned our attention from our own story to other people’s stories in some way. That our desire to have more dialogue in the performance with the audience or just having more dialogue with people in general has shifted the focus from us just talking about ourselves to us creating these opportunities for other people to talk about what they’re concerned about. And I think that’s a big difference

The General: I think one of the differences, is that this is one of the first shows where we haven’t had to make it totally obvious that we are lesbians and we have desire and sexuality. This is not a… I mean I guess you could call it a radical lesbian show, but we’re not radically lesbians in this show. In the 80’s or 90’s we always made sure we kissed or people knew we were in a relationship or whatever. But in this show our relationship is there because people know it now, and there are certain things that are accepted about it in the show which is personal, but part of the popularity of this show is that, and I worry about that a little bit, this is a show for the general public.

The President: Well yes it’s a show for the general public in that we are expressing an interest in a wide variety of opinions so it’s not just a lesbian opinion or even an LGBTQ opinion or even an older opinion, and we haven’t talked much about age or the Unexploited Ordinances side of things, but we are interested in what everyone’s worried about at the moment.

The General: And we’re interested in finding the truth.

The President: The truth and a connection. Part of what this show is about and this is interesting when you think about the difference between this and Lesbians Who Kill, is that we’re interested in making wide connections with a lot of different kinds of people who may even have a different opinion from us. Whereas Lesbians Who Kill, we were isolated in a car waiting out the storm and doing what we could do in terms of our own intimacy with each other to survive that storm. I think with Unexploded Ordinances we put ourselves into the center of the storm and said “C’mon y’all. If we’re going to survive we’re going to have to do this together. We’re going to all have to come out in the rain and manage this together.” So that feels like it’s different.

The General: And we’re trying at the same time, we have all the other things we’re dealing with, which are about desire, like wanting to show that old people are very interesting and funny and that old people are much more than people think they are. I don’t know what I was going to say.

The President: That’s good that you said that because I was going to go back to that with the title. Unexploited Ordinances whereas Lesbians Who Kill is a very obvious, out there title, you think you know what the show is about when you hear it. Unexploded Ordinances is a more literally hidden idea, literally Unexploded Ordinances, a buried bomb, or a buried piece of ammunition that hasn’t exploded and we’re using that as a metaphor for people’s unexplored potential and particularly how that is true for older people and how that might be a risk or a resource if you uncovered it. So it’s a kind of more hidden idea, the title, but when you get into the performance it’s kind of more open and out there and interested in what people have to say and actually, you’re right, we’re trying to find the humor and the beauty in older people and people in general, as well as their potentials and how those potentials might be a clue to how we’re going to survive?

The General: What we found is that it’s really hard to have men around the circle because they’re so disruptive. They stop everyone else from talking.

The President: *laughs* I know, well there is that. There is still the issue with the patriarchy. Some reason that word patriarchy is on my mind today. It’s not a name or a word that I carry around with me all the time, but it’s definitely on my mind today. But I think we have to wind it up a little bit with one more question. It goes back to, is this a radical lesbian show? And probably not, because we’re not performing as radical lesbians, we probably are performing as feminists. But I think it is a queer show. I think that we are queering a lot of things. I think we’re queering the theatrical experience because we’re inviting the audience onstage to perform and talk with us and they didn’t expect to do that. I think we’re queering Dr. Strangelove in the way that we take this on as women when it’s such a male, not just male dominated, it’s practically a totally male film. So I think that we are queering it.

The General: I think that we’ve combined the two things that we’re both working on. The strong drive behind the show was you because you had a concept which was a little different for us. Because of your social engagement work, that is not specifically radical lesbian, you wanted to combine that work with our performances which were lesbian, or we were in it. And all of a sudden we were in a cast of fourteen instead of just us. So it’s a combination of your new work, which is social engagement and our old work and we throw our old work in there often during the show because it’s very entertaining.

The President: Absolutely, and speaking of that, let’s end with what we started with. Let’s talk about the President and the General. You take on the idea like I said earlier, the archetype of the General, kind of in the character of George C. Scott. And he has, or she has, you as she, the General, have some Trumpian bombastic kind of characteristics and I take on the character of Peter Sellers as the kind of mild mannered, conciliatory President and we work those archetypes, but we also play and try to find the humor in those reenactments of those characters I suppose you could say. So I just want to know what do we like about doing that? What do we like about the General or the President? What do we like about taking on those characters that seems to work for this performance?

The General: The initial thing that came into my head was, as women we have the privilege now, or we have the opportunity to be the President and the General. And the combination of us as women and these outrageous comic characters of George C. SCott and Peter Sellers. But that’s nothing new for us. In order to have power, or more power in our shows we always embodied these male idiots. And we made them funny because rather than them, in the history of humor men made women funny, we’re making men funny. We’re making fun of men.

The President: We’re sort of taking on the concept of masculinity aren’t’ we? And that’s another thing that we’re queering and we’re doing it with humor we’re not just lambasting the idea of a male president or a male general, we’re satirizing it or making it funny.

The General: That’s another layer to the funniness of Dr. Strangelove. It makes it a different kind of funny because it’s women being the general and the president. I think it goes back to us originally trying to figure out what humor is anyway. Does it always have to be at someone’s expense? Or is it just a new thing that we’ve been trying to do? Because we’re doing Mike Nichols and Elaine May it makes it a different type of humor, but people still recognize that it’s their timing and that slickness that they had, they still recognize that, but it’s us taking on those roles which makes it a different level of humor.

The President: Right and more layers of humor so it becomes a more complex humor than just a mother and a son on the telephone. We’ve taken Nichols and May as the mother and son on the telephone and become like the president and the premiere of Russia in the film talking about the bomb about to drop and it’s Lois and Peggy. It’s sort of like three layers of things happening at the same time by taking on these characterizations. Talking about laughing about people or making people funny or making characters laughable we’ve always said that in order to do that, we’ve had to find aspects of those characters that we love or we absolutely identify with even if we do find those things problematic. What is it that you like about playing the General? What is it that you like about playing that part in this particular performance?

The General: I like it because it’s me playing a general. It gives me a certain right to be bombastic and ridiculous and interruptive in a planned way, rather than just the disruptive way. It’s planned into the show so that my aggression or my dimension of sometimes starting to sing or whatever is planned and not just masculinity taking over.

The President: That makes me think of something that you’ve been saying recently where you’ve been talking about trying to soften the effect of the Trump in you. Do you think it gives you the opportunity to, in other words, just talk about that for a few minutes?

The General: If Trump was not president, he’s very funny. I can’t believe he says things that I say about the government. He looks at things and says “This is ridiculous!”

The President: Right, right.

The General: He’s very funny especially lately as he’s losing it. He’s getting funnier and funnier.

The President: Well he’s dismissive and disruptive and anarchistic, gives no regard to protocol in the way that you like to be sometimes.

The General: Only when you’re trying to control millions of people and their minds and their money, that’s very disruptive. I don’t think I would have that kind of influence. But I do think that he is funny. So part of it, it’s almost like performing with a child fire thing, performing as Trump you can do anything you feel like because that’s okay, that’s acceptable. Because I just stand up suddenly and tell a joke and that’s very much in character. And you as Peter Sellers, you just fall right asleep.

The President: Well yeah, the thing I love about playing this version of Peter Sellers, is that I love being in the role of the moderator. I like being a diplomat. I think that would have been one of my other professions had I not gone into performance. I like the idea of looking at different ideas and listening to them and weaving them together and trying to come up with a solution. I do like moderating conversations and trying to help people to understand or express the thing that’s close to them and have that happen in public. So that aspect of being a conciliatory presidential diplomatic character, that’s something that satisfies something in me, but the other side of that is the absurdity of someone who’d not just fall asleep, but just could fall down on the table or fall off the table or could get ready to speak and then just not speak. You know that ability, it’s similar to yours but it’s a different quality which is also somewhat associated, I think, with age and something that we also talked about at the beginning of the conversation. That when you get to a certain age and your memory goes, well that’s kind of okay. When you get to this point where your behavior wasn’t, isn’t or can’t always be appropriate you go with that. So I think we’ve both found ways to look at inappropriate behavior in this particular kind of urgent, governmental, public setting and trying to make that okay so that we all feel somehow okay being who we are in this current context I think.

The General: Are you sure this is being recorded?

The President: Yeah, it’s all being recorded.

The General: Okay good.

The President: I think we’re done.

The General: I thought “Oh shit, I hope you’re not like Holly Hughes and forgot to turn it on.”

The President: No no, I think we’re done I’m going to stop now.

The General: Yeah, okay.

Lois Weaver (The President) and Peggy Shaw (The General) in UXO, 2018. Photo by: Theo Cote