Nadja Millner-Larsen: I thought this conversation should be mediated by this philosopher’s stone that you gifted me a couple weeks ago. Although, I believe my stone might be more accurately described as a study for another philosopher’s stone.

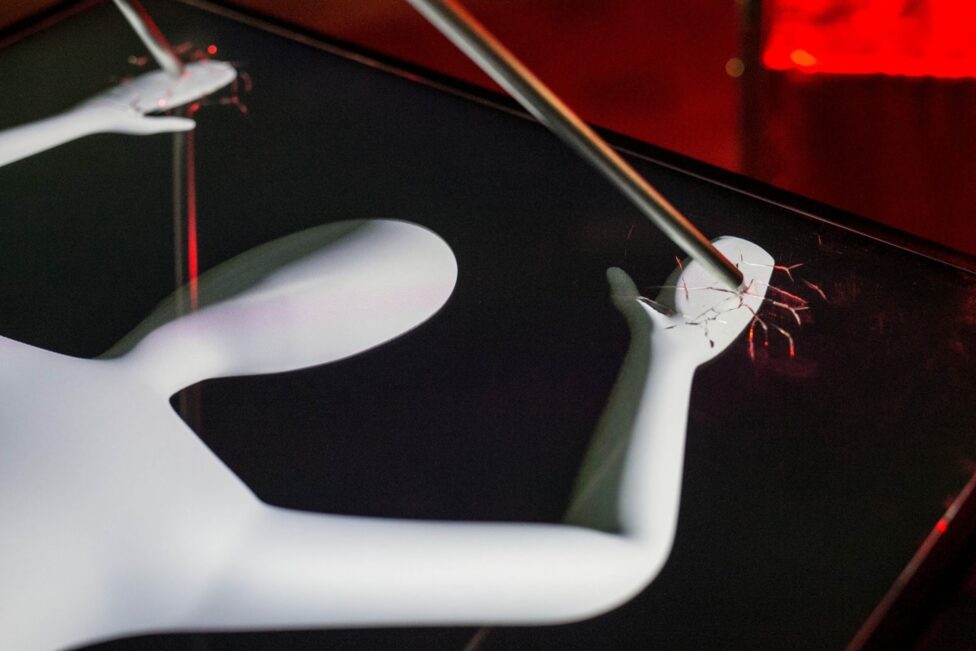

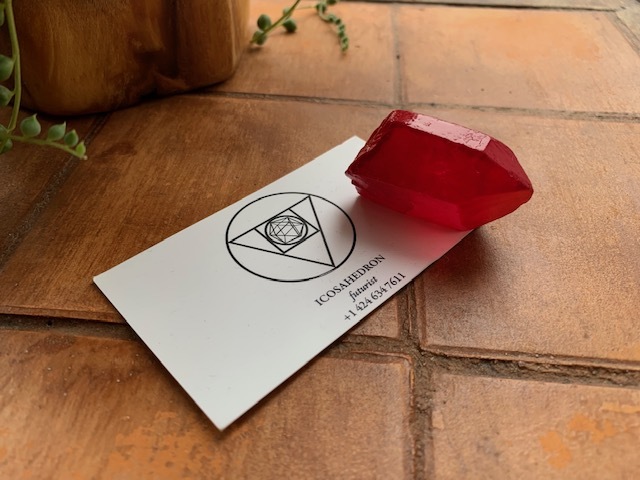

Zach Blas: Yes, another philosopher’s stone is currently sitting on top of a desk at the Walker Art Center. I’ve just premiered a new installation there called Icosahedron, which is an interactive artificial intelligence work that takes on California futurism and also the global tech industry’s obsession with predictive technologies today, such as predictive policing. I developed an AI that was trained on twenty texts both influential to and critical of Silicon Valley ideology—so from Ray Kurzweil to Ayn Rand, Ram Dass to Yuval Noah Harari. I chose twenty texts in order to structurally align the AI with the Magic 8-Ball, as this toy has an icosahedron, or twenty-sided die, inside that sets the limits of what it can predict. I was also quite fond of using the Magic 8-Ball as an object in which to serve critique, giving such Silicon Valley elite the level of criticism they deserve—childish. The installation itself is like a high fantasy of an elite tech worker’s desk—I like to imagine it’s Peter Thiel’s. Instead of a computer on this desk, there is a crystal ball with an elf inside that you can ask questions about the future. This emerges from my longstanding interest in Thiel’s company Palantir Technologies that gets its name from the crystal ball wizards use in The Lord of the Rings. In the past, I’ve called this “metric mysticism,” which describes how Silicon Valley companies deploy magic, mysticism, and fantasy to conceptualize working with data.

NML: I love how your practice employs all these talismanic objects that produce a particular visual lexicon for each piece: the philosopher’s stone, the crystal ball, even Nootropix’s book in Contra-Internet: Jubilee 2033 (2018) and the sex toys in the SANCTUM (2018) dungeon. These objects seem to function as mobile prostheses for the artwork that extend beyond their immediate appearance in a particular film or installation or lecture-performance. Like the philosopher’s stone, they become enchanted thought-tools that take on a life-world of their own which tends to bleed into new projects.

ZB: Yes, you’re definitely right that works bleed into each other, and I usually do imagine objects exceeding their installation context. I’m quite interested in diagrammatic thought, so I see the art objects as mappings that might try to conjure other futures or map unexpected historical relations or tease out an impulse driving a technical system or structure.

NML: I’m wondering about the status of horror and cruelty in your recent work. I have always thought of you as a kind of concrete utopianist, but there is a pretty menacing aspect to some of the material you’re producing right now. Your previous work has often referenced the violence of the image at an informational or computational level and we’ve seen references to 1970s punk (the “no future” refrain) but there is a more explicitly violating tenor that has emerged in your turn to body horror. Why has this become a useful genre for you to think with and make work with at this particular moment?

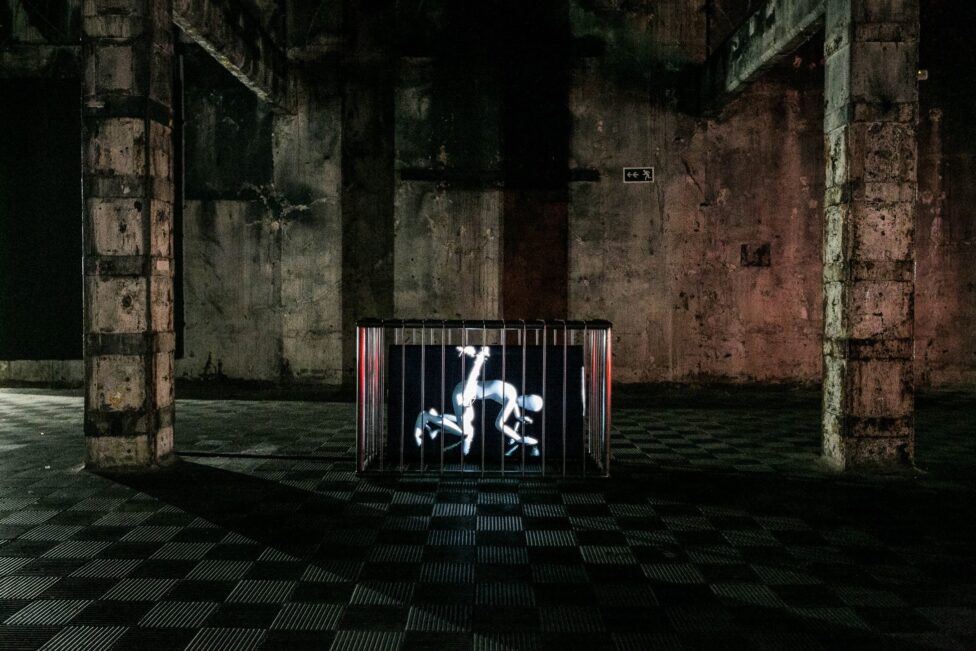

ZB: My work isn’t always just cruising utopia anymore. I partially see this as a break with my hacktivist/tactical media training. But also, when facing such complex technological systems of power, making a beeline to utopia doesn’t always make sense. I’m making work at the moment that is more about trying to understand power in these technical systems, whether artificial intelligence, biometric recognition, or the internet. For instance, SANCTUM, a large-scale, immersive installation that I made in 2018 at Matadero Madrid takes on airport security—as well as broader dynamics of exposure and digital surveillance—through a re-imagining of body horror cinema. I became quite obsessed with “generic mannequins,” which are the bodies displayed on the visual interface of airport body scanners. These cartoon figures—almost like the chalk outlines of dead bodies—visualize areas of the body that require additional, physical security inspection. I began to wonder what the after-hours life of the generic mannequin is at the airport, or put another way—what is the political unconscious of the airport? Part of that question is about space, for me. To address this, I created an installation that blends together a sex dungeon, detention center, religious temple, and weapons factory. With the generic mannequin as a main protagonist, I was trying to explore how digital surveillance and security today appropriate dynamics of BDSM and fold elements of this sexual practice into its machinations of power. This began to look like a new form of body horror to me. Unlike embodied things, the generic mannequin—as both digital and disembodied—can’t speak, can’t scream out, and doesn’t have insides or blood. Nor do they have genitals. If you are cruel to them, does this have any impact?

NML: So the body you mobilize in this work is reduced through a violent operation that while not appearing as horror—there’s no blood and guts—is nevertheless subject to a slew of technocratic cruelties inherent to the management of borders and populations. One of the things I find really generative about your practice is how you re-pose conceptual categories from theorists of technology and surveillance in the space of the artwork in a way that gives them a renewed legibility and urgency. Obviously, there is all the work you have done with the category of opacity, but it’s interesting to see you picking up on media theorist Katherine Hayles’s distinction between the body and embodiment in order to mobilize this new version of body horror.

ZB: I like to think of classic body horror films, such as The Fly by David Cronenberg, as embodiment horror, rather than body horror. And yes, I take a cue from media theorist Katherine Hayles’s distinction of the body vs. embodiment. For instance, the generic mannequin could be understood as a body, a biometric grid of a face could be a body. This particular interpretation of the body, in relation to embodiment, I find quite exciting to explore in relation to body horror. In part, because we’re actually living through this today, but also some of the major tenets of body horror cinema have to be reconsidered. As you mentioned, this newer, digital body horror does not exactly work through graphic, gory depiction. I think it has something to do with abstraction instead .

NML: This is really interesting to me because I kept wondering if your body horror work might bring Hayles’s distinction in conversation with another one that Hortense Spillers makes in “Mama’s Baby, Papa’s Maybe” between body and flesh. For Spillers, the “body” corresponds to a captive body and “flesh” to that of “liberated subject-positions.” Working from different contexts, both Hayles and Spillers posit the body as a violent abstraction from embodied flesh. Spillers is theorizing the discursive production of the captive body as an effect of Euro-American enslavement and its recurrent “crimes against the flesh.” Produced through the racial gendering of human cargo, the body is a particular organization of flesh but flesh could be organized otherwise. This raises a whole series of questions regarding the forms of flesh that fall out of liberal discourses of moral subjecthood and how such forms are both the condition of possibility for the making of the captive body as property and its site of potential contestation. This came up for me in relationship to your work in SANCTUM because it seems the viewer is forced to imagine a kind of pain (and desire!) that can’t be experienced by the flesh, only the body. At the level of appearance, this is a real departure from how classic body horror mobilizes the visuality of flesh – Cronenberg’s Videodrome being the primary example in my mind, when “the new flesh” totally merges with media.

ZB: That’s a great link between Hayles and Spillers! In SANCTUM, I created a scenario in which one of the generic mannequins is being harvested by having two douche hoses attached to its mouth and crotch. The hoses are sucking out a kind of metal liquid that gathers in a glass cube below. In the world of SANCTUM, this liquid, which I often imagine as bits of flesh that are residual, stuck to the captured body, and therefore transformed, is then used to make a variety of sex toys and torture objects. These objects are distributed throughout SANCTUM to provide both pleasure and punishment to the generic mannequins. So there is a constant feedback loop, between bodies and flesh. Additionally, the monitors are not to go unnoticed in SANCTUM, as they are, in another way, an embodied material substrate—or flesh?—to the mannequin’s normative body. I think of the extracted liquid as both coming out of the generic mannequin but also the monitor.

NML: It is really interesting to think about this recursive relationship between the generic mannequin and the sex toy-tool and the embodied personae from which this loop has been extracted. It makes me think of another contemporary example of body horror cinema in the film Get Out, where there is again this slippage between the site of the body, of flesh, and of objecthood. On a bit of a side note, I got really excited about watching the new Lorena Bobbit documentary when I saw that Jordan Peele was involved in the project because I thought he might somehow filter some of the more radical provocations regarding the body/embodiment from Get Out into this overdetermined story of dismemberment. But Bobbit’s amputated phallus is, of course, presented as a fetish object. The turn from contemporary body horror to documentary presents an occasion to rehearse all these tired medical/psychological discourses that naturalize the body as sovereign and whole. So in the first 20 minutes the viewer sees gory images of the lopped off member, a series of conventional re-enactments of the reattachment surgery, talking head interviews with various surgeons, doctors, law enforcement officials, etc. This is all intercut with some pretty remarkable archival footage (John Wayne Bobbit’s brothers on the Jenny Jones show) and interviews with journalist struggling over how to name and address the dick in print. All of this is clearly meant to underscore the continued cultural obsession with masculinity and its genital referent. But in the absence of any kind of discourse (visual or otherwise) regarding the “body” itself as a problematic site you get this kind of meeting of body horror and 20/20 true crime that renders all those issues around the reduction of personhood to the body (all that stuff that came up so brilliantly in Get Out) entirely moot. I found myself imagining how something really wild could have happened here—if it wasn’t hamstrung by the idioms of conventional documentary—where the dismembered penis gets rendered otherwise, perhaps becomes a dildo, maybe even travels through some dildotectonic contrasexual inversion experiment. You can tell I was thinking about another lecture-performance of yours – in which you perform a masturbating arm dildo exercise adapted from Paul Preciado – and wondering how you would be processing this documentary!

ZB: Preciado has a wonderful way of describing the difference between a dildo and a penis: a dildo could never be understood as a plastic penis, but a penis could be thought of as a meat dildo. The dildo is an anti-patriarchal diagrammatic form for Preciado, and according to the Contrasexual Manifesto, you can map out your entire body as a dildo, that is, the dildo as a diagrammatic technology can undo all sorts of gender/sex norms!

NML: There was a period in which you and I almost collaborated on a project on catastrophe, and we were thinking at the time about the mutually constitutive catastrophes of climate change, neoliberal governance and technocratic realism. That ship has long since sailed, but I do still think, in my own work now, about how the catastrophic has come to define our experience of the contemporary, and how that shapes our critical or aesthetic investments. Given this austere landscape, I’m wondering what place a certain politics of refusal might still play in your work, even as it perhaps moves away from the legacy of tactical media through which much of your earlier work was shaped.

ZB: I’m in the early stages of developing a film installation that explores Silicon Valley elites’ obsession with preparing for global catastrophe. Several of these persons, Peter Thiel included, have acquired property in New Zealand, as this is their exit strategy for when the world ends, whether that is ecological, social, a mix, etc. I have read that they use a euphemism to refer to these various potential global catastrophes, which is simply The Event. But for everyone else, it can be such a challenge to articulate refusal in the face of such epic crises. How does one refuse in a securitized world? Of course, there are micro-gestures. But how can this scale up?

NML: Yeah, it would require not only a technical intervention but also an ontological and epistemological one. What would it mean to refuse the contemporary horror show of surveillance and capture? You have to basically destroy a culture that sees those forms of transparency as necessary to its functioning.

ZB: I approach opacity, the flesh, and embodiment as ontological pathways to push against capture. I like imagining opacity as an onto-tactic, a combination of the ontological and tactical. Opacity is something that must be produced at the tactical level and just exists at an ontological one. I agree with you that a politics of refusal today would need to grasp both of these dimensions and work with them. In previous works, such as the anti-biometric masks I made, I understood that by enacting a tactical gesture around opacity an ontological claim is also being made. There are many variations on the concepts of refusal, opacity, and invisibility circulating today. One of my problems with some articulations of these ideas is that they need to be robustly developed in relation to the unequal dynamics of struggle. Some persons in this world are focused and consumed with issues that are a bit more immediately pressing than de-subjectification. Practically speaking, so many of these theories of refusal or de-subjectification are written (whether directly articulated in the theory or not) for a white male subject.

NML: Absolutely. The end of the world is not simply a process of de-subjectification. A number of scholars echoing Fanon (I’m thinking primarily of those working from an Afro-pessimist position) have argued that the end of the world is a process of resetting the coordinates of the colonial encounter, which requires an explosion. Decolonization isn’t a process of divestiture. It’s a re-foundational rupture.

ZB: How are you researching these ideas in relation to Black Mask?

NML: Debates about the politics of refusal and, in particular, the legitimacy of anti-colonial violence have become central to my research on Black Mask, an anarchist anti-art group active in New York in the 1960s, who were white by the way. To me, theirs is a politics of refusal that is particularly anti-redemptive in the sense that it doesn’t offer a “positive” alternative program but, rather, operates in a register of destruction that is expressly non-tactical. I am revising a chapter in my book right now about Black Mask’s 1968 transition into the group Up Against the Wall Motherfucker, a name they lifted from Baraka. Their first action under that name was organized in the midst of a sanitation strike when the streets of downtown Manhattan were covered in trash. The Motherfuckers took a symbolic portion of that garbage from the overflowing trash cans of the Lower East Side up to Lincoln Center – which miraculously remained garbage-free – where they threw it into the fountain. Obviously, the action’s transfer of refuse from downtown to uptown performed a critique of the uneven distribution of social services, and the attendant stratification of “high” versus “low” culture. But I’ve been focusing on how and why the group described this as a “non-tactical” action. In my understanding, it was non-tactical in two ways. First, it wasn’t explicitly organized in solidarity with the striking sanitation workers or to clean up their local neighborhood (after all, cleaning up the streets would make them scabs) and second, it operated within a modality of unreadability (beyond a “fuck you”) that the group associated with the form of the riot. The idea for the action came from a moment during the 1965 Watts rebellion when a group of protesters transferred a portion of trash from Watts to Beverly Hills. I see this use of refuse as paradigmatic of the group’s politics of refusal. Inspired, at least in part, by the writings of Fanon, the group took actions which sought to extend rather than resolve crises (like the sanitation strike) and could in part be seen as contributing to a project of bringing about the “end of the world.”

ZB: Non-tactical is so provocative today! Especially in relation to the popularity of social practice art—its institutionalization and perhaps even more specifically its mission of civil good. What do you think Black Mask would do if they were still active and asked to keynote a social practice conference?

NML: I don’t really see them attending a conference. Or maybe they would. But so much social practice work is organized to ameliorate the failures of the state or re-invigorate the use-value of art, which I think is fairly antithetical to the Motherfucker project. They were less interested in mitigation than they were in destruction. Regardless, the target has shifted now. In Black Mask’s time, one goal was to show the ways in which the state is entirely incorporated in the art world. Especially in the form of the police. So the idea was to perform actions that would put the police in a position of defending art, showing that they were therefore internal to art’s process of self-definition. The garbage action got the police to defend high culture by guarding Lincoln Center, thus showing the collusion between state violence and the culture industry. At other actions, at MoMA for example, the group’s protests sought to make that alignment between policing and museum culture more visible. I think you’re right that today there is this kind of entrepreneurial spirit to much social practice, so then the goal for a group like Black Mask (I imagine) would be to show the constant alignment and realignment between corporate volunteerism and the interests of the art world.

ZB: And how security plays into all of this! With its foreclosures of so many actions before they can be actualized. Most institutionalized art today is deeply complicit with security, and security lets certain futures march forward and others die. I wonder how you would bring about a different end of the world today—like in New York for instance, where you live? What story might you tell?

NML: Have you ever read Ishmael Reed’s Mumbo Jumbo?

ZB: No.

NML: I was led to Ishmael Reed through some of my work on Black Mask. Mumbo Jumbo is an amazing novel with a really complicated plot that I probably can’t do justice to right now. But basically there’s this African diasporic epidemic called Jes Grew that manifests as a dance – a chronic ass-shaking – that has quite literally gone viral. Jes Grew’s carriers include Papa LaBas of the Mumbo Jumbo Kathedral and the multiracial Mu’tafikah, a group of ex-art history students who loot New York’s museums (or, in Reed’s recasting, Centers for Art Detention) as part of a radical repatriation effort. Meanwhile, a conspiratorial group called the Wallflower Order is working to contain Jes Grew by grooming a “talking android,” a lobotomized black man filled up with white supremacist content (like a more weaponized Logan King in Get Out). The talking android is meant to infiltrate and sabotage the spread of Jes Grew, whose carriers are enlivened with the counter-modern rhythms of jazz, ragtime and blues. Reed writes about Jes Grew as a kind of anti-plague that will put an end to civilization as we know it, if those working to suppress it can be stopped. So I guess this is more psychedelic than denunciatory, but I’d start my story there – when Jes Grew has taken over the world.

ZB: My story would take place in England and start with a factual premise: in 2017, a storm carried sand from the Sahara and North Africa to London, turning its environment dusty and red.

NML: That actually happened? I’m looking it up…oh yeah: Storm Ophelia whips up dust from the Sahara! Maybe a sandstorm will come from Mexico? I’m trying to think of something in closer proximity to New York. Caribbean sandstorm unleashes viral dance!

ZB: End of the world!

NML: Well I should probably stop recording because we have to get you to the airport to engage in one of your choreographies of body horror.

ZB: Everyone becoming a generic mannequin: that’s one way I hope the world doesn’t end!