Leslie Cuyjet: I’m interested in a teaching practice as a creative practice, as a generative practice. And I know that you’re really engaged in teaching work and making work. I don’t want to treat this like an interview where I am asking all of the questions. Let’s treat this as a conversation that we would have in one of these Movement Research residency cohort meetings.

mayfield brooks: Yes! I received notice of the Movement Research residency at around the same time I started the farm in the Bronx. That was 2017.

LC: You had just moved back to New York?

mb: I moved back in the late summer of 2016. I was in a Performance Studies PhD program in Northwestern. The first year, we were able to get a masters degree and then decide, depending on the circumstances, whether to continue or not. Getting into that program was a highlight for me, I was really excited and I had a lot of hopes and one of the promises that they made to us as grad students was that there would be a focus on both practice and research. After the first quarter, I realized that the focus on practice was not their priority. It was a huge learning curve to train myself, discipline myself, to write and read at the speed that they required. So the first quarter was just super stressful and it just continued to be stressful. But, I figured out how to get into a rhythm with it and I figured out how to really get my practice going through the classes and through my own will, and I got through it. But in the end, I didn’t want to pursue the PhD. So I got my masters and moved back to New York. I had just gotten my MFA in 2014 at UC Davis, which is where I started developing Improvising While Black. I worked with undergrads and I taught dance classes and really started to come into my own with all of the work that I had been doing for many many years. My focus had always been improvisation. So once I actually got to grad school and had the time and space and support to develop this practice that I am now fully engaged with, Improvising While Black, it just came. And now fast forward, five years later, I feel that Improvising While Black is in a really fertile place because I am working with movement in a way that is informed by a kind of playfulness and improvised thinking. Everything that I move towards within the framework of Improvising While Black is almost like an afterthought. I’m not trying to push anything in the practice. The practice has to be fluid and constantly in an unknown.

LC: It’s in the action of the practice. The ritual of it and coming back to it is the learning of what it is.

mb: The kernel that this practice sprung from, was my experience of being incarcerated. So that experience, it affects the body, you know, the way you move in the world, it affects the way that you think.

LC: When were you incarcerated?

mb: Uhhh psheeeewww two thousand…it was 2003. Uh, so basically I was driving while black in the presidio in San Francisco. It was late at night. I was coming from up north. I had been driving for hours. And the speed limit in the presidio, it’s like a park, a national park, I don’t know, 35 miles per hour or something? I was going, maybe 15 over, 35 or whatever. And this cop pulls me over, he’s on a motorcycle, and decides to do a background check and apparently there was something there…

LC: oh fuck…

mb: They take my car. They handcuff me. He called for backup…

LC: Oh my god, how terrifying!

mb: It was terrifying. Then they put me in a cell in the presidio. They actually have like a cell there. Like an old school dungeon type cell. [chuckles]

LC: Like an old time sheriff’s office.

mb: Right. And then I was like, can you just take these handcuffs off? And they wouldn’t. I’m one person what am I gonna do? I’m not being aggressive. Then they put me in a car with these two white cops who bring me to…and this is like in the middle of the night okay…who bring me down to 850 Bryant which is the actual jail in San Francisco. On the way there these cops start blasting heavy metal music and turning their sirens on and just laughing and–

LC: Total tactic…

mb: Yeah! And then I get there to the jail and they put me in this cell and I’m with all of these women who look at me like, what are you doing here? [laughs] I was coming from Humboldt. …Humbolt is like super hippie, hippie country, in northern California, out in the woods. Ridiculous. They were just like, why are you in here? And I’m like I really don’t know why I am in here.

LC: I actually don’t know.

mb: I ended up giving this woman my jacket because she was so cold. Because I knew I was going to get out. My roommate came eventually and picked me up in the morning.

LC: That’s awful, I’m so sorry.

mb: I went back and I found out that, first of all, it had been a traffic ticket that I had gotten from five years before that turned into a warrant. They somehow mistakenly got it into the system as a criminal offense. So I went to the criminal court and they said, “this is not criminal.” This is a traffic violation. I go to traffic court, and they say “oh, this was adjudicated. You’re fine, you don’t have to pay anything.” Then I go to the police station and I talk to this black woman and she says “I am really sorry this happened to you. Probably the policeman who stopped you was just fulfilling his quota.” So “why did he have to arrest me?!” This is clearly a traffic violation, a non-arrestable offense. There was nothing.

LC: That’s almost worse. I mean I’m glad there was no reason they manufactured into something that was justifiable. But when you go through something like that and they’re like, “oh JK.” It’s like what?! That feeling that not only you’ve been treated unfairly, but you’ve been had. Like it was a scam. You’ve been scammed.

mb: And then, who knows what’s on your record after that. So that experience, even though it had happened ten years earlier, before I went to grad school, really affected me…

LC: Stays with you…

mayfield brooks photo: Malcolm X Betts

mb: And of course if affects how I think about what it means to be a black body and move through the world, what it means to be a black dancer and move, and what it means to have family members who are constantly in and out of that system. I started reading a lot of afro-pessimist writers. Some, who are just in the constellation of that thinking, not necessarily claiming the title. Saidiya Hartman talks about a “captive body,” this idea of the unthought. How the violence towards black bodies is so gratuitous that it’s not even something that’s thought of, and the reification of that. It was really important for me to center that in my work within the question of blackness. Not necessarily as an identity but as a structural position. So what comes out of that? And how can I play with that? How can I trouble that? How can I keep asking questions about that? I ended up writing my whole MFA thesis on this and doing a whole dance performance thesis on this and started locating somatic practices that made sense for this exploration. One of these somatic practices was limiting my senses. I had done Authentic Movement, but for me I had to come out of the framework of that practice and bring it into my own understanding of what it meant to be blindfolded. So instead of being blindfolded, I wore a veil. I started with a blindfold, but then I wondered what would a veil be like? I had always experimented with limiting, using scores that had to do with taking away the use of one body part. And how the movement can shift or my approach to dance or a space can shift while working in a sensory realm.

LC: That makes a lot of sense. Thinking about what you’ve shared about your project Letters to Marsha and how that idea of a phantom presence is also the phantom limb that you’re working with in your physical practice.

mb: The material just feels so abundant. Every step of the way, something surfaces. With Letters to Marsha, it became really clear to me that this ancestor came into my periphery in a way that offered me something, offered me hope. It was right around the time that I started working on the farm, and started working with Movement Research. It’s that post graduate school space where you’re in an incubator and you’re supported then you come out, and it’s like–

LC: Fly little chicken, fly!

mb: No job, no anything. I ended up having to work 7 days a week and I was working at least five different jobs. I remember this job that I had was in Chelsea, and I realized that the Chelsea Piers were not that far away and that Marsha had been there and, I just felt her presence. And it’s funny because I had this poster of her that was always very comforting to me and I had been carrying it around because I moved every year my last four years in San Francisco. Then I remembered that it was my friend, Micah Bazant, who had created this beautiful poster of her and I carried it around and I realized I didn’t have it and so I was like I need to find this poster, but I left mine in California. Micah told me to watch this documentary about her life. It’s on YouTube. It’s called, Pay it No Mind: The Life and Times of Marsha P. Johnson. And they’re just interviewing her and her friends. I watched that and I was like, oh my god. Everything she is saying felt so in alignment. I felt like the way she presented herself, her aesthetic, flowers, everything was so familiar. I said, I need to start communicating with this ancestor. And that opened up a whole other set of practices within Improvising while Black. I was working on the farm and I was trying to get it started. I started an herb garden and it was really important for me to have flowers in that garden in homage to her but also I wanted to attract pollinators. I wanted to create a kind of ecosystem that was very much alive. Not just grow vegetables and perennials. And that was my vision and it didn’t take that long. It really took off and at the same time I started studying her as a historical figure. I didn’t want to approach it in an academic way. I wanted to approach it as a curious person. As a friend.

LC: Referring to Marsha as an ancestor, it makes me wonder about our lineage. How are we connected? Whenever I go home, I go straight for the photo albums on my parents shelves and it feels like a creative interest. I want to look at and consider my lineage, in this creative way. It’s almost a ritual. There is nothing new there, it is always the same images, in the same order. A relic of a lineage feels important to my life as an individual and as a creative individual.

mb: When I am thinking about or engaging with Marsha, I’m sitting at the feet of my auntie. The auntie that is now here for me. Also, someone who can understand me. Because of her life story, I can approach my life story more freely. To approach her life in an academic sense felt like it would be erasing that aspect of the relationship. The way that it has filled my life is unbelievable. I feel like I have been walking with an ancestor for the past three years, who continually fills my life. My duty to her is to continually be the recorder, to be the one who listens, who writes, who archives, who is present. Sometimes I wonder if I will be writing her the rest of my life.

LC: What does it feel like to write these letters? I am curious because of my interest in my great-aunt who I am trying to figure out how best to resurrect in our minds, specifically in dance history, because she was omitted. I have always been interested in what it feels like to engage in this letter writing practice. I know her granddaughter, I have connections to her, but for some reason I am not drawn to picking up the phone and talking to her granddaughter. There is a more indirect path that feels more directly connected to the path I want to have.

mb: What happens for me is that I am creating an imaginary space. As part of my practice, I wanted the imaginary to be at the forefront of the work. That space has been so attacked, the way Toni Morrison, when she is an interview, people attack her. She holds her ground. She is working within that imaginary space but it is based on real life stories. They come to her, she channeled them. That is the space that I am working with. That is what I want to bring into embodiment — who can we be fully in our imagination and drop all of the expectations of what you are supposed to do or what you think you are doing. Let’s get scared. Approach something you don’t know. It can be really uncomfortable but once people go into that space there is something that gets released. As my relationship with Marsha develops, I see my practice bursting open into this elemental space. Lately I have been working with decomposition as a conceptual framework. I put my body under compost, under decaying flowers, the echoes of Marsha, and I let the weight of that organic material literally change the way my body is or what my body can do. It is becoming a practice. It is an interesting shift in the work. It wasn’t expected.

LC: It so clearly ties the dirt and matter of your farming into your work, into your performance. I met Ysanet Batista last month who is super passionate about food justice, and who was working on her first cookbook proposal. We were cooking together and as soon as we were done, she said that everyone could go start dinner but that she had to write. In the action of cooking, she had gotten so many ideas. When she was making a potato salad, she was cutting the steamed potatoes in her hand with a really dull knife, she said “this is how my grandmother did it, we didn’t have any sharp knives, we would over-boil the potatoes and cut them in our hands, this has to go in my cookbook!” We were wrist deep in the food and I watched her light up with all these ideas. It makes me think about you and being body deep in the dirt, pulling weeds from the garden and you’re like I need to get in the dirt.

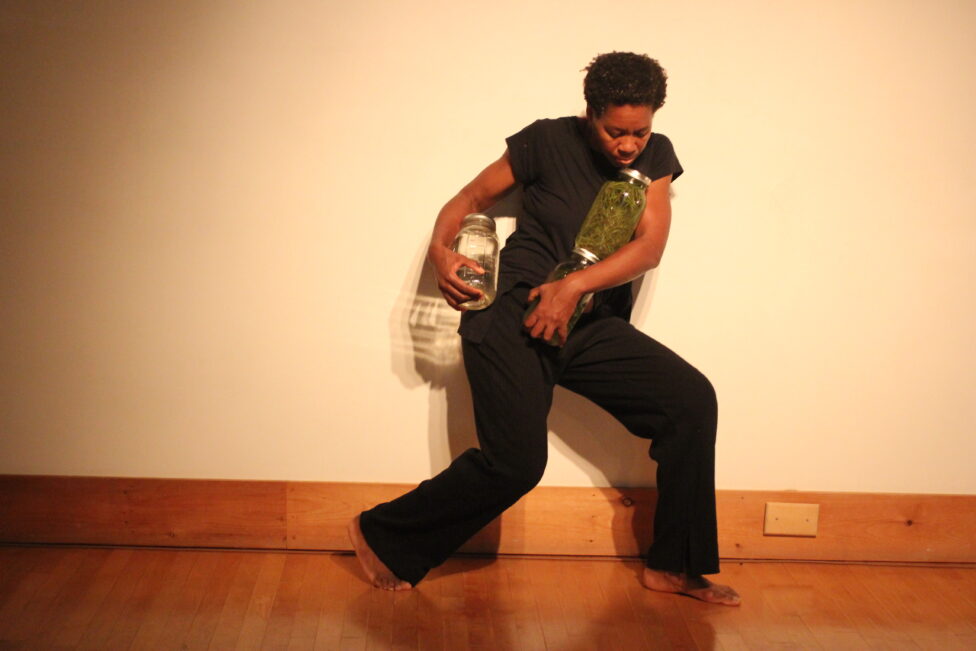

mb: It worked out that way, and it was important for me to do a harvest Viewing Hours. I had done a spring one at The Kitchen in April. That moment at Mt. Tremper was glorious. I arrived at Mt. Tremper in October, it was peak foliage. I had to trust the process. I needed to get water from the creek, I needed to get compost, I had a lot to do and it was only me doing it. Until I invited people for a black sleepover. I invited you! I wanted to bring black folks to this land, I wanted to share this space. About 10 people came. And I did the ritual for them too. It was so beautiful to be there with folks and emerge from it and sit with folks and really commune with folks and the folks that were there. And then I performed it that evening for the public showing. I danced myself out of the dirt and went into the studio and took a shower and then the dance continued. The water I had gotten from the creek was in all of these mason jars and I had this whole choreography where I danced with jars. I introduced them, I am dancing with the Esopus creek that flows into the Hudson, and they are going to be my dance partners tonight. The hilarious thing that happened was that the jars, once I started dancing with them, exploded. There is a photo of me with the jars that I have to show you. They broke! There was glass everywhere!

LC: WHAT?!! Whoa!

mb: There was one jar that didn’t break. I was holding the one that didn’t break and stepped back and all these people knew what to do, they came in and cleaned up the water and the glass. I went and put on another costume and came back out and was like that wasn’t expected and then helped clean. I was playing the Julius Eastman music and it perfectly matched the clean up. A whole choreography emerged. So this is what happens when you work with ancestors, I said to the audience. It was incredible. I am going to do the piece at JACK in January. I am thinking about that transition. It is going to be in the winter in a whole other seasonal situation. I am working with an urban farmer and the florist who I worked with at the Kitchen. We’ll see. I plan to get under the material and come out. What is gonna happen after that?! The elemental aspect of this piece is so strong. I guess now there is a cleansing aspect. When I come out of the dirt I have to shed that layer and move into the watery space. When I first started Letters to Marsha, it was really narrative and now it is elemental. This is what I have been working towards; what is the impression of this process and how to communicate that to the audience.

LC: I am engaged in all these research practices and processes. I was in rehearsal with Stephanie Acosta. I love what she is doing. She comes with a whole library set up in the studio. We write and we talk and we move some and I had this assignment to work on a score. I go over to the library and I looked through a Kerry James Marshall book and then I went and moved. What came out was so different than what I was pre-planning. It was like a twenty minute free-write, leafing through that book, just loosening up the brain by taking in this information and then leaving it to go move. I wasn’t thinking about it, but it was there, it was in me. I am always interested in that, what is that transfer?

mb: It is just being with whatever you are working with. I brought books, I brought letters, and when I set up the space, all the books were there, all my writing was there, all the different costumes I had worn over the past years were there. I had a slideshow of Marsha and a cacophony of her voice that went along with the slideshow. Flowers and letters were strung up around the room. I made a love song playlist, the letters are love letters; letters about wondering how do I love myself, how do I love others, how do I love my ancestors, how do I love in order to heal. That is the crux of the work. How do I heal the tragic story of her death. All these endings. Her body in the water, our ancestors bodies in the water. I created an installation with all the material that had been informing the piece. It doesn’t have to show up anywhere in the performance but if that is something that you are working with, it will get in there. There is an embodiment of all of the different layers of the work if you open up to it.

Letters to Marsha with Viewing Hours (a diptych) will be at JACK in Brooklyn, January 30 – February 1, 2020.