Gillian Walsh: What was so moving to me about seeing this performance is that dance, as you know, is such an obscure form. It’s not in language, a lot of people don’t understand it, and often the people who see dance and care about it are other dance people. So to come to Borough Hall, just protesting every day, showing up different places, different actions, and then see this dance happen unexpectedly, so seamlessly in between people giving speeches and marching really set me on fire. It was amazing to see this whole audience of people coming together for the purpose of this movement, seamlessly making space for a stage, sitting down, and watching this dance so attentively and really receiving this work. It’s very unusual to see a large group of people in the public really focus so intentionally on dance. How did you get involved with this action?

Tiffany Rae: I’m sure it is no mistake, I’m sure it is Gods doing, but it was literally last minute. I’ve just been protesting, I’m just looking up protests and I see this student march is looking for speakers. I said, okay, great, I should just sign up. I messaged them and said I didn’t mind speaking, but that I’m also a dancer and choreographer and if there was a way I could perform or do something. And I didn’t think they got back to me because they had a lot of followers and likes and I thought they wouldn’t even see my message because a lot of people are probably trying to do it but they wrote me back two days before the protest and were just like, hey I would love for you to the dance. And then from there, I tried to get five good people, because you know, it’s quarantine, it’s hard to get people but we made it work. And they way the audience separated too just to sit down.

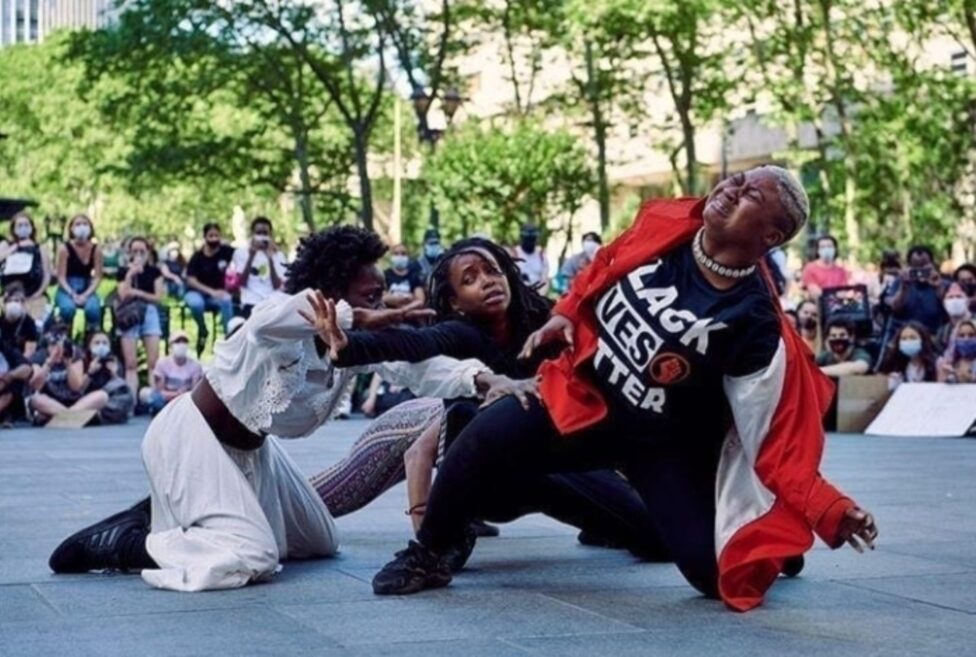

GW: Yes! I was so shocked I’ve never seen an audience behave like that in my life. They really just separated and sat down no problem and they watched with real focus. Underground is such a full-blown and complete multiple person choreography which really separates it stylistically from other dances I’ve been seeing out in the protests. I’ve seen a lot of great dance at protests, mostly spontaneous and improvisatory. I love seeing people dancing at protests, but what struck me about Underground is it’s a fully choreographed multiple person choreography straight out of quarantine. How did you make Underground?

TR: I actually put that piece together last year believe it or not. It was a really big performance for 30 dancers at the Sybarite showcase. It’s this big dance showcase, especially if you’re a hip hop dancer in New York or LA. I had been dancing with other people there for years and I decided it was time to do my own piece and really send the message up there for the dance community about our culture and about how Black Lives Matter. Black culture has influenced the dance community so much and it’s really hard for a Black girl, especially for Black dancers.

GW: How do you feel like your activism and dance inform one another and work together?

TR: Dance is what speaks to me most so that’s the language I use. And I don’t just talk about Black Lives Matter, I talk about gay lives, I talk about the thick girls in the dance community, and I just talk about everything. This is the time to get together and talk about what’s going on and create about it, whether you’re doing art, whether you’re doing poetry, whatever you do. This is the time to create for the movement that’s going on. Enough is enough, it’s 2020. We should not be still talking about this. But after seeing some of the videos going around, I’m like, have we made any progress? People are saying like, Oh Rayshard Brooks, he resisted arrest, but he should not have been shot, period, and nobody deserves that. He had a daughter, he had family. People gotta understand, if it was a white person or another race, it wouldn’t have come to that. Go back to the Charleston shooting where the 21-year-old white male shot and killed people in church, and the cops took him to Burger King to get him a burger. I find that really ridiculous…. If a Black man came and killed nine white people in a church, they would have never stopped to get him a burger…

GW: No, they would’ve killed him.

TR: They would have killed him. And that’s just a fact. Enough is enough. I love that everyone is involved, I need everyone to be involved. I feel like it’s everyone’s job now. Black lives are really under attack. There’s a lot of times where I’ve been profiled, I remember me and my fiancé were outside the projects in the Bronx and a cop ran up behind us for on reason. I’m just like, we really have to get them out of our neighborhoods, because that’s just ridiculous.

GW: The version of Underground I saw at Borough Hall had five performers – what was it like as a 30 person dance?

TR: I wanted to talk about what it’s like to fight for something all your life, and you can’t even reach it. There’s a dancer who’s dressed like a police officer, he represents not just police but white supremacy. He represents all the problems right now, and grabs our lives out of our hands. Our breath is taken out of our bodies, we can’t breathe anymore. We can’t fight any longer, there Is nothing more we can give. I had a child, a little boy, standing over us and representing the next generation. I wanted to show the trauma that’s really being passed down generation after generation. I don’t think people understand that the type of trauma slavery has done to us. And we’re still fighting today, 2020, and it’s kind of ridiculous. That’s where I started with this piece. I talk about dancing, slavery, the current times of growing up in the hood what that has put on us. That put a lot on us. People don’t realize that a lot of Black people are put into systems where we’re set up. Set up to fail.

GW: When did you start making dances?

Photo: Jenny Anderson

TR: I feel like I’ve been doing this since college as far as using dance to talk about the problems that I go through. I went to Queensborough and I’ve been dancing for a long time before that too, my mother was a dancer. She’s always been dancing, she went to college for dance and dancing ever since. I was actually in her belly when she was teaching dance. Once I turned five and she didn’t have someone to babysit me, she would take me to work at the dance studio and instead of me sitting on the side, I would dance and I would get up and try to learn. From there, I’ve just been dancing ever since and she taught me everything.

GW: What kind of dance did your mom do?

TR: She really did it all, ballet, African, West African, modern, contemporary, jazz. She just didn’t do hip-hop. I started out doing ballet and modern and jazz at the studio with my mom and then from there, we were in the projects and she didn’t have money for me to go to dance classes. I couldn’t afford to take classes, so I went to the community center, and I learned hip-hop and that’s where I started to infuse everything. I support defunding the police because all that money that’s going into Police could be going into our community, especially the community centers. Because for people like me, if it wasn’t for the community center, I probably wouldn’t be the person or dancer I am today. That’s why I’m so important to defund the police.

GW: What shifted when your dance life moved from the studio to the community center?

TR: It was more of a community, people from all walks of life, people I saw from around my neighborhood all coming together to learn something and dance at the center. It was an amazing time, it was my first time doing hip hop. I would do competitions with my mother, but it was like jazz and modern and contemporary. And with this, it was all hip hop competitions. And it really was a lot of experience. I think at the time we had a lot of funding, so we were able to go do this and that, but once the funding stopped, we stayed at the center.

GW: What were the competitions like?

TR: It’s an amazing feeling because you see all types of dancing, all types of movement styles. I’ve been competing since I was five, whether it’s a jazz competition or in the community center, or with my mom. I also was a cheerleader and we won a National Championship.

GW: In Underground there’s so much movement and so many choreographic influences coming together. I noticed so many different styles, I saw some contemporary, Ailey, modern and hip hop, and dance theater. Each dancer had such a different aesthetic character, I’m curious about how you’re bringing your choreographic influences together in there.

TR: The four categories I started with for this piece were the underground, the hood, the bloods and myself. The first category was the underground, the first generation, slavery time, so I had people who represented 400 years ago, when slavery was really, really brutal. I wanted to demonstrate a fighting for freedom pushing through with grace. Not exactly peaceful, but a graceful fight. I thought of the feeling of Harriet Tubman bringing people from the underground. I wanted it to be graceful, turning and flowing, trying to reach the north star, using their legs and their whole bodies to reach up. Even then you see they’re crawling, they’re trying to reach up. The second one, I called them the hood, I wanted to express what actually happens in the ghetto, like current day and how people really can’t catch a break. It’s the now, people in the hood today, the people who are so directly affected by what our ancestors went through and what has passed down from generation to generation. We have a lot of teens who are dropouts, especially a lot of gay teens who are dropouts. There’s a lot of teens who have no place to go, and we become the stereotype of how all Black people are. So this character is representative of people who don’t have a voice but they’re just trying to fight. The hoods were more hip hop influence. There’s a lot of anger, and just not having it anymore. Not so graceful, not so much modern, it’s straight hip hop. Full hip hop.

The third one was the bloods, they’re more like enough is enough. This is the actual blood shed, people who died for us, burning things down, this is Malcolm X. This character is almost like our spirits in a way. So with the bloods, I had the movements be sharper, more aggressive. I tried to make it more modern-based infused with hip-hop, and more gestures with arms and body. And for the last category, myself, I was more of all of that in between. Because for me, I’m the one that actually made it, even though for generations, we’ve been hurt, we’ve been knocked down, but I was able get a college education, I was able to do this and that and look, even still, I’m that token one who “made it”, but I still can’t get what I need. I’m that person that didn’t have to go through all of that but I’m still experiencing racism, I’m still experiencing colorism, I still experience this. As far as the choreography of everything, a lot of the movement is from me freestyling and improvising and it’s just what spoke to me of the characters. I want to show that all these dances are all one within me.

GW: There was a really interesting blend of style, there was a lot of concert dance which was so unexpected at a protest and so much true visceral power woven into the theatrics of all of it. There’s visual moments that are very representative and theatrical, and then there’s these moments that are so emotional and subtly embodied through different recognizable forms. Can you talk about the ending?

TR: We are out of breath, our breath is being taken away. And this was last year that I made this and it’s crazy that even today, it has so much meaning, especially with what happened with George Floyd. They took his breakaway, he couldn’t breathe. And I didn’t tell the dancers how to do it, I just showed them from my improvisation, I would tell them I want you to do it yourselves. I want you to have your own improvisation, I want you to feel what this means to you. I said, imagine someone taking your vocal cords from you, how would you react… I want you to try to catch your breath but your breath is gone. And all of that last part is a freestyle, nothing planned. Sometimes it might be more angry and active, sometimes it’s sad and melting away, it changes. And even at Borough Hall like we were supposed to be all down on the ground at the end but like I said that parts all improvisation and whatever you feel in that moment.

GW: The dancer in the white dress reached up at the end.

TR: Her character was reaching up like, I got y’all, I died for y’all. And because she really put herself in the piece 100% and really felt it, she was able to be like okay this is the moment in the story where I change it, this is the moment where I’m gonna say I died for you and I’m still reaching for you. I’m still reaching for all you guys and I’m still here.

GW: It felt like everyone in the whole audience really felt the power of that moment too. There was a stillness in the air. There is a box that everyone reaches for in Underground and is ultimately stolen by the police officer character. What is the box?

TR: I wanted to express the pain and trauma of generations and generations of what my community has been through. Even today, I go to the store and I’m getting followed around, they don’t know who I am, they don’t know that I went to college, they don’t see that I’m a good person, they just see, this Black girl with her fiancé, two gay Black girls and they’re just following us and I’m just like, what world are we living in? So it doesn’t matter if I “made it” or I got some successful job, it doesn’t matter. I still can’t reach that box, I still can’t get the box. That’s why at the end, I showed the police officer, the white person, grab the box, because sometimes it’s not even intentional, sometimes you don’t even know you’re grabbing it, it’s not even your fault, sometimes that’s just destined because of the history that we have built. Generations of this unfairness. That’s what I wanted to show in my piece, and I wanted that to read. Each character is trying to reach for the box each time but it just doesn’t work, but the white performer could come through and he could grab the box any time he wants, because that’s just the way of life.

GW: What do you hope this movement can accomplish?

Photo: Jenny Anderson

TR: Our community has nothing. Kids are going hungry because schools are closed. They’re making sure Black families aren’t educated. They’re not making it easy. I feel like in this movement I can’t be naïve and be like I want equality now, it’s not gonna happen overnight. We need money put into our communities, we need to totally defund the police. This is a priority. I heard they’re trying to cut a billion dollars of police funding, if you can cut a billion and be good how much do they even have?

GW: About 6 billion.

TR: That is sick. That is sick. That is disgusting. We need access to housing. All we have is NYCHA, the projects, where a majority of Black communities are living. It’s literally a 10 year wait to get it to NYCHA. It’s ridiculous. We need housing, we need jobs and we really need education. I had to stop college when I was about to graduate because I didn’t have money, I didn’t have anything, I was struggling, and that’s just the process to me. I don’t have parents giving me money and support. I have to worry about where I’m gonna sleep, how I’m getting housing, how I’m gonna pay my bills. In the Black community, even children and teens have to worry about paying bills, so we can’t focus on our life like our white counterparts can. They get to focus on school, they get to focus on their careers, while we can’t focus on our careers, that’s why we have no careers. We need more programs, we need education, we need more opportunities, we need more support for people who have been in jail. I think they feel like they’re doing enough by giving us a little bone sometimes, and the problem is that sometimes we accept it. Instead of us accepting it we need to really say no and reject the small reforms. We deserve more. This isn’t just an idea, this is my life story. All of this has been passed down and down again and again. I’m breaking that chain. I’m not having it and I’m not gonna settle. Especially as a Black woman, it’s time for us to get together, I feel like we’re at the bottom of the totem pole. Did you hear about the recent killing of Toyin Salau? It just keeps happening. And even with Breonna Taylor there’s still no Justice for her. There’s not as big of an uproar for Breonna Taylor as there is for George Floyd. We have to put the same energy for our Black women as well, and those cops that killed her need to face consequences. It’s ridiculous. And look at her, she did everything she had to do, she has a great job, an apartment with her boyfriend. And look, it doesn’t matter. She was shot and killed in her own apartment and there’s no consequences for that. At this point, we need some new structures put in place, so that’s the overall goal right now. We need our communities funded now, we’re not gonna keep waiting for somebody to die. We need to keep it up.

GW: Can you talk about your previous piece, Made for Now?

TR: I create not just about Black Lives Matter, but gay lives and I try to do a lot for the gay community in general. Made For Now was about gay homeless people and giving back to that community. It was about my life, when I was about 21 I was homeless and I was in a drop-in center, a gay drop in center, and it was really hard. Once I got out of the situation, I just started wanting to create more about my life and others I knew along the way that went through the same thing. I wanted to show how the Center actually helped, and just putting work out there to say there’s so much more and you’re not alone. I used some of the workers from the center in the project, and I also dedicated that piece to the center, too. I really want to see more funding go into the gay Black community especially centers that help Black gay teens. They don’t have the funds and resources they need. They don’t have the real estate, the apartments, the space to put teens in, there are so many gay teens living on the street, living on the trains. So that’s really why I did that dance.

GW: You have this quote that I really liked in your interview in the Cut where you were saying dance takes you out of reality, that dance is a place to kind of imagine a different reality, and I feel like that really speaks to how it can be used as this activist tool, or a potentially utopian tool, not necessarily just in an explicitly politically active way, but just a way to imagine different worlds and different ways of relating to one another.

TR: Yes, dance is therapy for me. It’s a conversation you have with yourself and your body. It lets me know that things are gonna be okay. It’s therapeutic for everyone. Since I started dancing when I was five whenever I felt sad or depressed or anything else – I would dance. I don’t go to therapy, I’ve never been to therapy, dance is my therapy. It’s a lot bigger and has the ability to express far more than words and brings a different conversation. I feel like if I didn’t have dance I’d be in the worst place possible. I think dance has saved a lot of lives especially in the gay community and the ballroom scene. People vogue and compete with their houses and it takes you to a different place. It takes your full energy and sometimes you forget everything else. Right now is a time I’m dancing so much more than ever, because there’s so much pain. So sometimes I do just need to do something fun, some hip hop or one of the Tik Tok dances. That pain needs to be released. Dance just brings you into a different reality of something that’s not really there, it can help you imagine that things are different.

GW: Even if it’s not a specific scenario or a specific vision that you’re imagining it’s the experience of dance being able to change your state from whatever is happening to something different, so whether it’s a really simple change in emotional state or an energetic thing or a projection of an alternate reality that could occur, it’s such a powerful mode for change, like both very subtle and individual, and collective. What changes would you like to see in the dance world?

TR: Type casting is number one, as far as the commercial hip hop industry. Black girls are not getting booked, I remember there was a Lizzo audition, and they specifically called for thick Black girls, and there were still white people out there and I’m just like, guys, let us have just one thing! I feel like I work so hard, but I don’t get the recognition that I should be getting and I think it’s simply because of my skin color, being a Black girl, and as far as the dance industry, it’s harder for us girls who are thicker as well.

GW: Was it shocking to see white dancers show up to the Lizzo audition anyway?

TR: No, of course they did. For the dance community it’s really nothing new. You still have white people who do afrobeat, and a lot of white people who do hip hop, and we accept them because I guess dance is more of an accepting community than the regular outside world, but we do have to remember that there are a lot of people who just take the culture, take everything, they make money from it and that’s it. They exploit us. So that definitely needs to change. We need more opportunities for Black women in general.

GW: What are your hopes for your dancing and choreography?

Photo: Jenny Anderson

TR: I definitely feel like it’s so important for me to do my own work because at the end of the day, I can’t just rely on anybody else, because obviously the community right now is not supportive of Black women so I have to make it myself. We have to do it for us. My goal is to just keep doing what I’m doing and try to reach a bigger and bigger audiences. I want to bring the message to as many people as possible. My goal as a dancer is definitely to go on a tour and eventually to be a tour choreographer and I want to open a dance studio when I’m well established – Tiffany Rae Dance Studio – for my community. Hopefully I can get some funding. I definitely want to provide a place for people in my community who can’t afford dance class like myself when I was little so I want to give back in that way.