Ronaldo Wilson: How are you doing? It’s good to see you!

jaamil olawale kosoko: You too! I’m curious about this artwork in back of you.

RW: Oh, this is a painting where I committed to painting with X-Acto knives. They’re pretty large, I’d say, two feet by three feet, or something like that pretty large scale for me — a series of family portraits. This one is of my father, from a sequence, somewhere in the middle of 100 drawings that evolved into these shapes. I started these when he was quite sick. I didn’t know he was going to die — but I realized as I was making these pieces, they were important. I might take some of the drawings to Provincetown where I’m going to go back to work with the artist Fred Liang. I worked with him virtually last year in a drawing intensive class at the Fine Arts Work Center, out of which this drawing emerged, but I’m going to work with him in person this summer in Printmaking, so I’ll perhaps revisit these works. What about yours? What’s happening behind you?

JK: A similar but different portrait, a moving portrait of my brother, actually. I am basically working with light and projection. This is the visual capture of fractals moving in space. So in this way, this portrait of him is reimagined, translated, broken into light and movement, and, I can continue to visit him, be in his aura, if you will, even when I’m working within this digital space.

RW: I love it. It’s very powerful. The dimensions of light fractals, as you say. But also really tenderly the way you get to be with him.

JK: With so much of my work, I’m trying to figure out immortal strategies for staying in touch, for conversation and communion with the non-living, with those I’ve lost to understand how I might continue to engage with them now, even in their afterlives — because they still move with me. They still activate, and operate, and stir, and inspire. I feel them. Memory is funny, right? Even after such a long time, the memory and those essences linger; they still inspire me to create work and impact my execution of art making quite deeply.

RW: Yeah, it’s beautiful. I understand what you’re saying. I’ve been sitting with your Wendy’s Subway book. I’ve been reading it. It’s Black Body Amnesia, right?

JK: Yeah, that’s it. Did you forget? Did you have an amnesic moment?

RW: It’s interesting, I was nervous, and had a moment of shame in forgetting the title, but I was so invested in the contents of your book that I decided to not be ashamed and just blurt out what I felt was the title! I was just now thinking about the urgency of forgetting as a formal mode of revisiting the “liveness” that you talk about in your work in terms of a couple of things. One, is this idea of what liveness is, how it’s simultaneously an act of accretion within the living moments as it manifests between the living and the dead. Secondly, in this way, I think there’s a kinship around physicality in our work, people we’ve sort of floated with, in lineage, and conversation. But I think there’s something around knowing that the kind of fragility of death and of living, and understanding how to hold onto the kind of livewire resin, what it is that you are called to remember in life as the material for an art making practice. I was thinking about my dad — I’m writing a lot about him now. I was invited by the critic and curator Genji Amino to write in conversation with his grandfather, the Japanese American sculptor Leo Genji Amino on race and abstraction for his first and only retrospective volume, and in doing so, I found myself writing about my relationship to my father, a kind of ekphrastic project that had to do with these really physical, living acts, hitting a backhand on the rise in tennis, opening up the shot to make sure that I get enough top on the ball to not be afraid of a high kicking serve — something my dad taught me, which I knew was really important. Those are the things I hold onto. I knew this was valuable when he was teaching it — precious, as precious as when he died. That information, I think, is maybe something I want to interpose in our discussion in kinship, our material approaches in understanding the value of our mutual appreciation of lineages, which has to do with also being curious and surprised and, you know, not afraid of them, and I can only say that because of my answer to your question with the title of your book, which I moved through within a kind of living dance of shame!

JK: Never, no need. No need for the shame dance to emerge.

RW: It’ll probably be a funny dance.

JK: I mean, if either you or I are creating a dance of shame, I’d be really curious to see that actually. Having seen only a glimpse of you live at McDowell, which was just such a treat — and I think that was the moment where I really leaned into this interdisciplinary, multidisciplinary, multi-sensory, interdimensional, intertextual way in which you’re blending images, and moving through them, and processing while re-processing while dubbing and creating — it’s just such a treat to observe. I feel we share a similar connection to objects — it feels like we have a similar sort of connection to objects, masks, masking, garmenting.

RW: Yeah, completely. It’s wonderful to hear you talk through it and to find these shared points because I think counterintuitively, or maybe even directly, that is our relationship to interiority.

JK: Oh my god. That part.

RW: This is the kind of tribal connection. Perhaps there’s something deeply palpable and important understanding that there’s a PICC line to the heart of the object, the heart of what we’re getting at. I just love our shorthand understanding of the importance of the object, as well as the gallery, and dance — but we don’t trade up for any of these for anything. I think we’re rendering what’s important across these disciplines within our own interiority. And I feel that in your work — I felt this as soon as I saw you for the first time at McDowell, actually. The first time I saw you walking, I was like, oh, okay.

JK: Interiority.

RW: Shrouded in black hat and gorgeous fabrics, moving along the McDowell terrain. I was like, oh, okay. He’s alive, internally. This one has heart! To me, it was this kind of signal. I’m thinking about your conversation with Bill T. Jones in Black Body Amnesia. I love the way your rendering of Afropessimism, and your encapsulation of it as a way into the thematic that fuels some of your practice. You remind me: We can’t forget Baldwin. We can’t forget Lorde. We can’t forget Clifton. I can’t forget all these people who I know are getting at the same material in related ways, but I think it’s just a different language. But what I love is that I trust you because you’re getting at questions of mourning, of loss, of indelible sorrow through objects and performance. Your archive is really, I think, another connection that we share. What I love is the multiple of ways you’re testifying to these different figures and studies. Testifying. Test-if-why! All of the ways you’re playing with material, I think, are extremely important. I don’t think they’re arbitrary. They’re not interchangeable.…because these things break. They fall apart. They melt. They rip.

JK: They do. I’m in the practice now of finally really being able to showcase this archive through bookmaking, through exhibition-making, through installation-making, through performance-making, through film and video and moving-image. This work is finding an outlet, really by any means necessary, a moment to be present, if only for a moment. I’m doing the best that I can to really create the circumstance and the container, the environment, to best showcase these worldings, as it were, because I do feel like we are in this practice of seriality. For me, there’s something that is speaking to this way we’re thinking about vision and recycling. There’s something about passionate non-attachment, with allowing the things to break, acknowledging the temporality. I think that’s why performance, as a practice, feels important to me — because it reminds me of the delicateness of the moment. You know, we’re only fractions of ourselves in the timespan of the universe. It’s like, did we even happen? This is something I’m really thinking about: systems of interiority. For me it is so important. It’s a non negotiable, Ronaldo. I need a certain amount of personal, private incubation, refuge, interior space-making, world-making time or else I’m just absolutely useless. I don’t know. It’s so important to me.

RW: There’s a great intentionality in your work in that regard.

[image description: Ronaldo V. Wilson crouches in a garage space, his left arm extending forward and his face cast downward. The space is empty. Light presses in from the windows across the garage door and on the adjacent wall. The image is blurred with the remnants of motion. Video still from Wilson’s My Virgil Heart, 2017. Courtesy of the artist.]

JK: Yes. I think there’s something intimate, too. There’s something about the intimacy as it is connected to that solitude. Or maybe it’s not solitude. Maybe that’s not what’s being communicated. I don’t think it’s solitude, per se. But it is an expression of selfness, and a need, really, to testify, to share.

RW: Yes, for sure Jaamil. I think the profundity with which you’re exploring the kind of cyclical nature of death, what you call a “re-inheritance,” has to do with the subtlety of the ways you reveal knowing. I haven’t had the pleasure of seeing you in performance live yet — but maybe it was one in Berlin in your book — where you recount wearing your brother’s shoes in memoriam and simultaneously as a kind of performance catapult. I think of Kevin Beasley – his sculpture of light blood-like tinged polyurethane coated sneakers hanging as death-life speakers. He does all this amazing textured, sonic work. You know his work. I don’t know why I thought of that, but I think it has to do with how you negotiate these tentacular relationships, building connections to mourning in which one is utterly alone, in what might be the heart of how you also re-render Afropessimism, right? Which might be the Blues, or really what I see as rigor in the face of catastrophe. How we wear it. But I really respond deeply to what you’re doing because I have no language for it. I just feel it. The theory, I might say something about it. But your work, I just don’t think I can say as much as I experience it. I really simply enjoy the idea of just thinking of us working together in this world that you’re constantly deconstructing building, refashioning, and simultaneously mining through deep excavations of grief, and even deeper ways through which to live.

JK: I do feel, of course, the connection you’re making. You know, I’m with you there. But this last point, just around ways in which we continue to cycle back or move back towards ways of reimagining. I’ve been thinking a lot about Black radical death studies as a way of acknowledging, or bringing a deeper attention to my practice of living. Because there’s been so much of it, I just have a deep intimacy with it, with death. I feel like as Black people we’re kind of forced into this deep intimacy with death and dying, you know? It’s inescapable. I think what you’re observing is an attempt at accepting this relationship, this brutal truth, and figuring out how I might propose a way of performing through it for myself?

RW: I think of a poem — the poem that you wrote called “Stank.”

JK: Oh, sure, yeah.

RW: I think a lot about how that operates, death in life. Part of my mother’s mourning of my father is eased with my sister’s family dog, “Bear”-on loan, but basically living full time with my mom, cute little thing that last week brought in a dead bird for my mom: “That dead bird smells like death!…That dead bird smells like death!” I couldn’t escape my mother’s repeating phrase. I know my mother has a very particular relationship to death, her parents were assassinated, she worked in the Philippines in leper colonies, and she also worked in convalescent homes most of her adult life and lost mostly all of her patients, a sort of quotidian relationship to death. All of those factors you’re talking about come into these lived moments, lived histories. One thing I know, in terms of scholarship and working as a scholar and as an artist, is there’s no kind of secondary work that can quite get at it. Death smell. Maybe it’s my literary response. I have to get rid of Proust. I think of your writing of your care of your uncle. I have to release J.L. Austin. Get rid of all that they promise to absorb another essence. At some basic level, I think that what you’re talking about is gesture as critical death study. Touching it, through the worlding you’re talking about — building the whole performance around sensation. And the trust in knowing that there’s a body of work that emits from this. One of the things I was thinking about is Audre Lorde’s Zami, and your own Biomythography. I remember encountering Lorde’s life-changing work as a young reader before I’d ever even thought about “memoir,” before I ever thought about “biography” as categories. And of course, I was thinking about your work in relationship to Lorde, myth and how your work offers a similar freshness..

JK: Yeah, for sure. And what could be possible? So much of what that text and the genre, if you will, were able to open up for me was a kind of queer home where I had not had one before. It really felt like she created this space, this gateway, that is like, here’s a blueprint for a way that you can piece together your own context, how you describe yourself, who you are. It just gave me permission to write the kind of book and to put the kind of book together that I wanted to put together. It helped to have that creative license and to work with Wendy’s Subway and Omnivore — an incredible team of people to really listen to that vision and help me pull it together and execute it. I feel so incredibly grateful for that to have been my first major experience pulling a text like this together, so that I know that process, because I imagine it won’t always be that way.

[image description: jaamil olawale kosoko, dressed in a draped brown dress and gold-beaded headdress, stands with their torso contorted to the viewer’s right and arms extended outward on a rocky beach. The sky is an ominous blue. Photo by Freddie Koh. Courtesy of the artist.]

RW: I can relate. My first book Narrative of the Life of the Brown Boy and The White Man, is speaking to Lorde’s text a little bit, particularly in how I understood the importance, to borrow your language, the blueprint of its erotics, its sense of primacy. Years ago, I was invited to a commemoration for Lorde’s Zami at the Schomburg, and I remember talking about the sequence where a very young Lorde is holding an even younger baby-girl on the porch in a snow-suit, trying to excavate the erotics of that moment, enlivened by the possibility of the nurturing and, for me, the pedophilic. It was a fancy room, and I was just maybe thinking or writing out loud, and recall reading my piece and upsetting different folks at this event, but like you, for me, Lorde’s work gave me, too, a way to try to exact perhaps an illicit erotics. You don’t know that you’re going to be in these conversations, say some 20 years later, and you realize, oh, this is why this book was made! This is why Lorde’s story was told in such a palpable form, for us. I’m also still taken in Zami where she’s older, eating metal and plastic computer chips in the factory she worked at, ingesting materials clearly carcinogenic. Her work reveals instructive moments, (let’s hold close her Cancer Journals), like yes this is red hot and complicated, and I also have to figure something else out as a writer and artist, a lineage that reveals such life and death, right?

JK: When I think about that — going back to this idea of inheritance, and inheritance as a result of loss – I’ve been trying to really re-cast my memory of loss, specifically familial loss, with my parents and siblings. How might I think about this differently? How might I repurpose and use and cherish the memories of these people, and transcribe them, because I do really feel like it’s a part of my obligation, Ronaldo, through telling my story, to tell their stories as well. So when I am performing, even as the soloist that I am, I feel that I’m in community with my mother, and my father, and my brother, and my sister. There’s this family that is very much present that I’m still trying to acknowledge and just say, “Hey, I feel you. I know you. I’m doing this for us, for our legacy, for our memory. Your lives were not in vain. You meant so much to me. And I will let the world know — whoever cares about me and my world — know that truth.”

RW: It’s beautiful what you say because what I hear you talking about goes back to this notion of material, that your actual presence is the material memory which occurs in performance — maybe in language, in gesture, maybe in story. I think that’s our vocabulary. And that vocabulary is something truly profound, which addresses both the memory and the respect of the family, but also the curiousness and the messiness of stinking bodies, of shit left on the sheets, vomit, all that stuff of life. I have these crystal clear revelations when I’m swimming. And I realized when I was swimming today that I just have to face the facts: I am fully invested in experimental strategies, and making work that is just sometimes not going to be read, and people are just not going to understand — or maybe they’ll get it maybe they won’t — but I’m fully committed to this for the rest of my life. I’m just going to keep doing this and I know that this is the way I have to go on. I could do these other things, right? Get an agent, do this, do that because I kind of feel something’s happening in the work gaining a certain visibility, but I still want to maintain this idea of perhaps what you’re calling to “know the truth.” Perhaps mine is that I’m always going to do the thing that’s just wrong. Do the wrong thing.

JK: Do the wrong thing in the best way possible.

RW: Right? It opens up that glimmer you’re talking about. It opens up the ears just enough to hear, or the nose just enough to smell, or to see the little blues. I love your attention to — let’s not call it the accident, right?

JK: The circumstance, the situation.

RW: Brilliant. Thank you! Thank you! Mature artist, Thank You!. I’m still emerging…I’m just a poet who happens to be like, okay, I’m gonna try this now. Like, okay, this feels good. I think that that’s where you’re deeply attuned to what you’re making as an artist and confident around it, and rightfully so!

JK: I love it. I fucking love it.

RW: It’s important. It reminds me of Gwendolyn Brooks’s Report from Part Two where she includes all of these pithy, deeply profound introductions for writers. Some of them are just, like, two or three sentences, right? She returns to the word “confidence,” what it means to be a confident poet seems everything for her. Welcome to the stage. And it’s just so right. Just the confidence you have in knowing the situation, the circumstance is the accident, is why.

JK: It also makes it less fearful, because I think I’m really excited about reimagining the fear. All of the things that I think scare me, I’m like, “Oh, okay, I have to lean into that. That’s information. Why is this exciting me? Scaring me? There’s something hot here. I have to move further in that direction.” I’m learning to listen to the fear in a different way, to accept it, and to accept it as information to allow for whatever we want to call the next moment. It makes that even more powerful. I also feel I’ve created a circumstance that allows for failure to exist without being the be-all-and-end-all. Like, we need this failure. Let us all get used to this failure. Let us all laugh at this failure. Let me make a comment about it. Let us reimagine it together so we can go someplace else, so we can move beyond it. I love those happy accidents, you know, those accidental, performative moments, because I think they open up so much incredible information and opportunity.

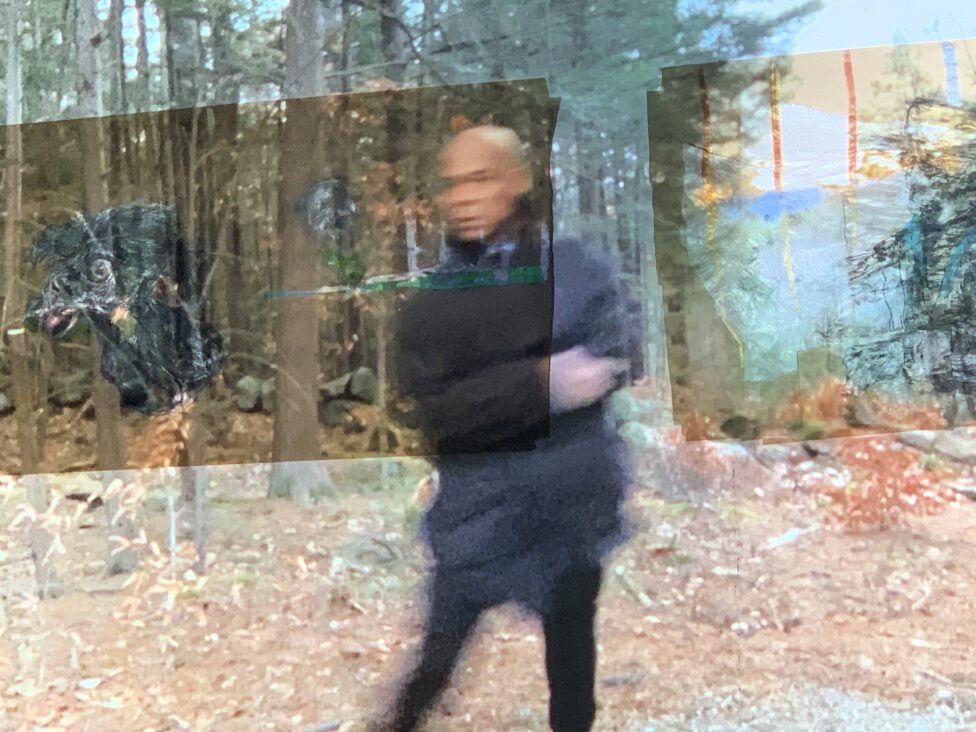

[image description: Ronaldo V. Wilson stands at the edge of a forest with his arms crossed over his chest and his right leg bent slightly behind him. On overlay of other images, including that of a black-haired bird, hover above each of his shoulders. Video collage still, Noa, Lio, and Uba, 2021, by Ronaldo V. Wilson. Courtesy of the artist.]

RW: I’m thinking about what you said earlier in this context: we are all fractions, right? I wouldn’t be able to relate to this as directly if I hadn’t dedicated myself to a regular drawing process over the years. That was important. The first drawings I ever committed to appear in Farther Traveler, a practice of just sitting with these these lynched, photographed Black bodies, and rendering them as human beings in just pen, my writing pen, actually. In fact, I didn’t even know there was a difference between a writing pen and a drawing pen, so when I started an actual studio practice with an art teacher, he pointed out the distinctions. To me, they were the same thing, but I realized, over time, that the mark of a drawing marker is so different from the pen. Perhaps this is a part of being a fraction, of recognizing these fine distinctions, especially in looking back at my drawings and illustrations over time. In drawing — I don’t even know what’s happening. I suddenly see a face. I see my mother. I see my brother. If I am drawing my mother, at some point the image looks like my brother as a child, my young mom, then my niece, moving between the real and the imagined. Drawing does something to the psyche, whereas when I talk about it, I just can’t speak any more without feeling close to weeping.There’s this urgent feeling of connection not marked in the same way as writing, perhaps allowing me a way to get closer to all of the mistakes. And I respond to what you’re saying in terms of performance in the drawing, because I think that’s really my purest form of expression. What I think I was born to do is to draw, and everything else just is sort of an accident, to go back to that word. That’s a scary thing to say, but if I lean into that reality, who knows?

JK: I love your fearlessness, though, and the approach of the gesture, of the mark, the marking gesture, the gestural mark. I feel there’s a similar intention and purpose for me in regards to why make that mark, that gestural mark? I’ve been exploring drip painting, and that’s been opening up a whole other dimension of creativity and color and shape and world-making, to really just zoom into these colors and how they’re pushing against each other, colliding, molding, melting. It’s a very sensual practice. It’s been really nice for me to explore that a bit.

RW: What you say makes me think about that moment when you’re in conversation with Bill T. Jones, and he says, “First the body is wet, then it’s dry.” And I think of these drip paintings in relation to your fearlessness and care, your committing to the emission, and the recognition of it as the thing, as the being, right? I love that.

JK: The secretion — something about this secretion and the movement and just allowing it to be what it is. I can’t wait to make the visual process film of these paintings. Wow, thank you for this lovely convo Ronaldo. Time to run to the next meeting.

RW: I’ve loved this conversation. It’s right and it’s inspiring. So you have to Go Do You!…My only meeting today is to hang out at my sister’s pool!

JK: Oh, fun. Yes, that’s the assignment. I just ask that you send me a picture at some point of you enjoying this pool time.

RW: All right, I will, for sure. Well, it’s so good to talk with you, and I know we’re going to keep talking. I love sitting with your work. It’s brilliant, by the way, as you know, as you feel, as you are.

[cover image description: jaamil lies on their side across the floor of a white-walled living room. Two beige chairs sit behind them on either side of a white radiator. Small wooden boxes, a sparkling mask and other assorted items side atop the radiator. A large window, its shades drawn, and its thin blue curtains draped along its crown, constitutes the majority of the back wall. Image from kosoko’s Black Body Amnesia: Poems and Other Speech Acts (Wendy’s Subway, 2022). Courtesy of the artist and Wendy’s Subway.]