A note from Jmy James Kidd, guest-editor

I wanted to work on this Cancer Dancer project for reasons similar to why I have created the organizations / communities / spaces throughout my life like AUNTS is Dance and Pieter Performance Space – something I needed that wasn’t available yet, or available to me, or available in a way I found inviting. I would have loved to have found the support / inspiration / camaraderie of a range of written experiences, images and videos by dancers who had or have cancer in their lives when I got my diagnosis and went through many, many treatments. Arriving on the “other side of cancer” I found myself cleaved into me as cancer patient that couldn’t really believe what I just went through and a new me that was completely lost and empty – who am I, who am I now? Reaching out to other dancer people that I know and that I don’t know, responding to my own writing prompts, peering into and sharing my own experience with myself and others, connecting to these incredible humans that are part of Cancer Dancer is part of my personal integration project that I hope offers insight and support to dancers as well as caregivers as well as anyone, should they find themselves with a god damn cancer diagnosis. I was interested in Dancers writing as Dancer People; from the rhythms, vocabulary, way of their own dance trainings, practices and lives. So much love to Kyoko Takenaka, Roya Carreras, Lindsey Red-tail, Sue Roginski whose writings had me in tears, laughter and deep respect. A resource guide, compiled by us all, can be found online at Pieter Performance Space.

Cancer Dancer Resource Guide on Pieter website: https://www.pieterpasd.com/cancer-dancer-resources

In butoh and Japanese traditional arts, the concept of MA “間” is continually reiterated. The silence or space in between two notes, or your body in between embodying two different realities or states of being; whether that be the silence in between two hits on the wadaiko, or the unnameable space in between embodying two textures merging together. Like starting a meditation practice, attempting to grasp this concept can be maddening. Sure, theoretically that’s beautiful, but we live under capitalism, and I need to keep it moving. I need it to work, for it to be a profound experience, right away. I need four advils for my period. Japanese cough suppressants for my unrecognizable cough. I need markers of progress. I need a tempo, a script, a choreo; I need cues to know where to land. How can we make space for something that we cannot grasp? How can we be sure that it is happening, that we are understanding the journey “correctly”? How could I ever become so comfortable with an altered state of reality, where nothing is clear, where I wait for answers that I can never quite mark the progress of?

In January of 2024, I planned to join my butoh dance teachers on Yakushima Island in Kagoshima, Japan. Instead, I facetimed my seventy-five-year-old butoh teacher from New York City to tell her that, at not even half her age, I’d just been diagnosed with cancer. She told me, confidently, to forget the chemotherapy I was prescribed: “Just come on over here and heal yourself in nature. There are people on the island who healed their own cancer here!”

That wasn’t really what I needed to hear at the time, as my Hodgkin’s lymphoma was diagnosed at stage 3B, my health deteriorating. I tabled her innocent enthusiasm and went on my way to Los Angeles, where I had chosen family who could thankfully help take care of me and drive me to my appointments. I was one of the lucky ones, I have one of the lucky cancers – almost every oncologist, surgeon, or nurse would tell me, while I endured six months of aggressive chemotherapy, and my whole world shifted. Again, not really what I needed to hear at the time, but perhaps a good precursor to the next year or decade. People tell you their opinions on cancer as if they are facts, project unsolicited narratives based on their experiences, or those of their parents or aunts. Why not test my own threshold for finding my own footing from the beginning of this journey?

I mapped out, journaled, and yang’d my way through – a clear journey for 2024. The moment I accepted and publicly announced my diagnosis to my community, I would enter a year of healing and come out on the other side, healed; a 2.0 version of me with a clear image of before and after. I imagined myself doing butoh dance during my infusion sessions and filming it. Actually dancing and filming at the beginning, I thought hey, aren’t I pretty well-equipped to handle this as an artist and educator? I can follow the footsteps of artists like Fred Ho or Audre Lorde. I signed up for Qi Gong teaching intensives and Reiki one-on-one trainings in-between my infusion sessions. I signed up for the free therapy that was offered to me through cancer support centers and talked through all of my family traumas. I sent letters and boundaried all of the abusive people in my life. I imagined recording my solo album with all this time I had to myself and planned to finally master my meditation practice. I would be diligent about watching all the movies, no, cinema, on the forever list of essential films I finally had the time to watch. I would become a macrobiotic king and flourish, sharing sugar-free recipes and someday writing a cookbook.

Instead, at some point, I lost my drive for any of these things. I stopped making music or moving my body or making sense of anything. I was in bed for one week straight at a time, ordering rubbery fried chicken on Uber Eats and eating out of plastic containers. I became terribly afraid of creating negative associations with the things I loved during such a nauseating time. Some things that I ate the day of my chemotherapy I still cannot eat to this day. So I stopped eating the things that I loved most. I stopped making music. And I stopped dancing and working so diligently at my healing practice. Rebelling, if you will, to do nothing. Come to think of it, it was the first time in my life where I felt I was allowed and encouraged to rest: not hustling, not being on call, not applying to another grant or project as I had every waking or even dreaming moment of my life as a freelance artist. Not rest as resistance, but rest, just as rest.

The only things I really stuck with were photography and filmmaking. These two mediums, I felt, allowed me to time-travel and plant seeds, to be able to process and make meaning of this time later.

I was the most depressed, panicked, confused, and mad I had ever been. I was grieving miserably, but for once in agreement with my body’s state and not fighting it, masking it, or trying to make sense of it all. I was fuming and spiraling at the dis/ease and worry I had held in my body for so long, perhaps because of intergenerational family traumas. I was livid at my doctors who misdiagnosed me for years and years, still owing money to this day for years of misprescribed medication that had made me sicker. I was mad at this country’s healthcare system – that I am only alive because somehow I was lucky enough to have generous friends who fundraised for my cancer treatment through the goodwill of our community, while my tax dollars helped fund free healthcare for a genocidal state abroad.

I was upset for my friends who were upset for me when I still drove myself to auditions the day after chemotherapy even though it was dangerous for me to be around people, being extremely immuno-compromised and anemic, just for the chance not to lose my health insurance next year and to prove that I had worked, and prove my deserving – my deserving to live, to have healthcare. So many of us in the so-called United States have to prove that we are worthy to live. Worthy because we are good, working, obedient people. Then, maybe, we would be granted the ability to not worry about our parents getting murdered in a hate crime; our aunties being kidnapped by ICE; our friends and partners being shot by the police for making a U-turn; our trans siblings losing access to the medicine they need for their survival; and on, and on and on. But we know none of these things are guaranteed, regardless of our efforts to prove, to understand, and to know, and that is devastating.

“Is the pain and despair that surround me a result of cancer, or has it just been released by cancer?” Audre Lorde in her book, cancer journals, talks about the “function of cancer in a profit economy.” As I looked around in my everything-is-chaos, the mountain-is-burning 2024 state, I couldn’t help but see cancer as a synonymous word with what everyone was feeling around me: the function of genocide in a profit economy, the function of the American healthcare system, racism, fascism, war, apathy, and so on and so on. Truly at many points during and after my chemotherapy journey, I couldn’t even tell what I was stressed, crying, or screaming about. Was I stressed about being diagnosed and about having to continue chemotherapy even though I was in remission? Or was I stressed about our crumbling planet, or that I was helping to fund genocide and couldn’t be out in the streets? Or that my community around me was telling me to please rest and keep my stress levels down, while internally, it felt more painful to suppress my stress than to be one with everyone, screaming into the abyss? When Lorde states that “imposed silence about any area of our lives is a tool for separation,” yes, this was about being public about cancer, but it felt just as relevant to being vocal about the fight for life and liberation in Palestine. It’s just as relevant to the violence and micro-aggressions that all of us hold in our bodies every day, that some say turn into the root of disease.

Cancer has been a way for me to connect to the grief left in my body, and to the grief in knowing that all things are interconnected, to the unknown. It has been the lens for me to murkily feel and connect to the deep, unexplained, unerupted grief of the world, and to connect with others experiencing it too, whether they willingly volunteered for the journey or not. It doesn’t mean that I understand or can explain it, but I do feel it deeply.

“Hold your sorrow to a degree of eloquence, whereby everyone around you will be fed by your efforts to do so.”

– Stephen Jenkinson

“There is some strange intimacy between grief and aliveness, some sacred exchange between what seems unbearable and what is most exquisitely alive. Through this, I have come to have a lasting faith in grief.“

– Frances Weller

I was truly at an all-time low mentally, emotionally, and physically. I began to accumulate stress about trying to find work immediately to pay for my apartment in Los Angeles after chemotherapy. I didn’t think I could afford it with all of the upcoming medical appointments. I panicked and sublet my place. I visited my butoh teacher, who nudged me again: “Go to Yakushima. You’re not healed yet. Drink the water there, and heal in nature.” This time, her advice resonated.

When words fail us, how can we lean into lessons from nature to teach us about the strength and resilience of our bodies? How can we remember to lean into the unknown – the unknown which is the core abyss, the birthplace of creation for our artistic practice?

Chemotherapy felt like a psychedelic drug in so many ways, so many life revelations screaming all at once, so many life lessons happening so quickly and urgently. How do you want to spend this time? What is important to you, right now? What did you learn from this experience? What are you going to share with the world?

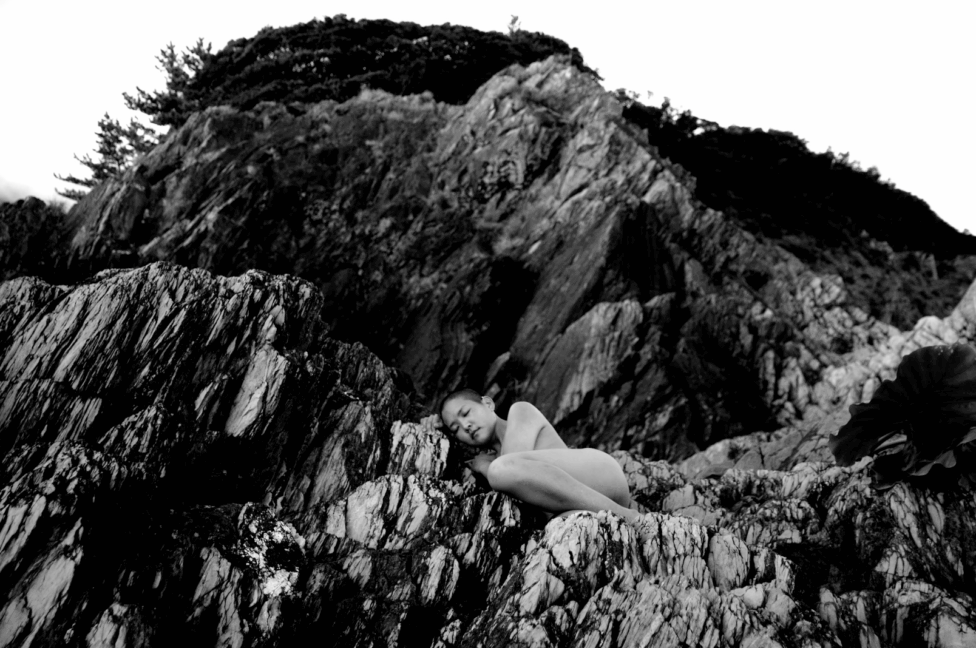

Whenever I feel my mind racing and excavating so hard that my head begins to hurt, I try to return to my body. But at the time, my body felt so foreign to me. I hadn’t danced in nearly six months. I lost a lot of weight. I’d been sick for years even before that, having been misdiagnosed for so long, internally holding on by a thread at every performance. Chemo brain and steroids clouded any internally-guided intuition left in my mind and body.

Not even two weeks after my port surgery removal, while the stitch was still bandaged, I sublet my place and spent my accrued miles on three flights to Yakushima Island.

I met a beautiful dancer and light-filled being named Meibi in her sixties, the friend my teacher mentioned who had healed her own cancer. She was diagnosed with breast cancer in Tokyo and decided to move to Yakushima to be in nature with cleaner air. She told me this unbelievable story of how one evening during a rainstorm, she remembered the moment the cancer left her body after she was laughing so hard with her friends all night that her belly hurt. She went to the oncologist the next day and they told her that the tumor had shrunk and disappeared.

I had such an incredible time and wanted to stay in Yakushima, but my indecisiveness was at an all-time high and I decided to keep my flight back to New York, as there was a huge typhoon warning across Japan.

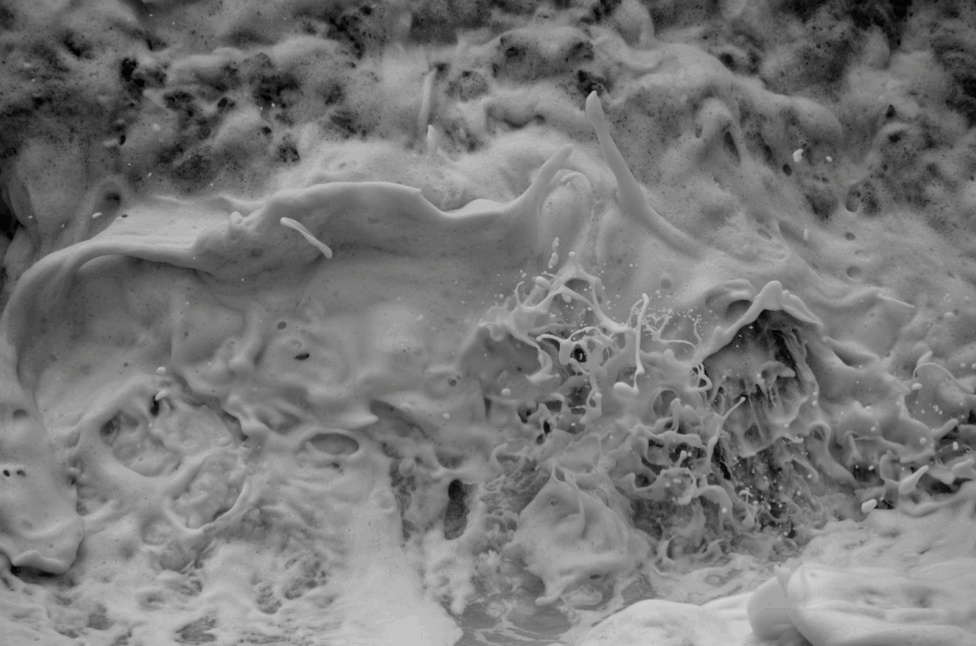

Arriving back to New York, my yearning to be back in Yakushima grew exponentially by the hour. I wanted to be in the thick of the storm with my new friends who lived there, so so badly. I felt the strong beat of this metaphorical storm from an apartment in New York, journaling every night while requesting hour-by-hour photo updates from my photographer friend in Yakushima.

The typhoon paralleled my year battling cancer. We just have to sit through it. There is nothing to do but sit inside and wait. Wait for the worst of it to pass. After the storm creates destruction, it leaves room for new sprouts that were previously stunted or lacked exposure to the sunlight due to the louder and taller trees blocking them. The sprouts finally thrive and are able to grow and create a new environment. Something about meeting my impatience with physicality, forcing my body to physically sit through a storm, made the prospect of flying all the way back to Yakushima even more enticing, and exactly the crevice I wished to indulge in. I was painting a vivid inner world and feeling it all in my body as if I was there experiencing it, like performance art in my body.

I couldn’t take my yearning anymore, so I sublet my place again and flew all the way back to Yakushima the next month even though the storm was over. Mind you, this was still all in the same year I went through chemotherapy.

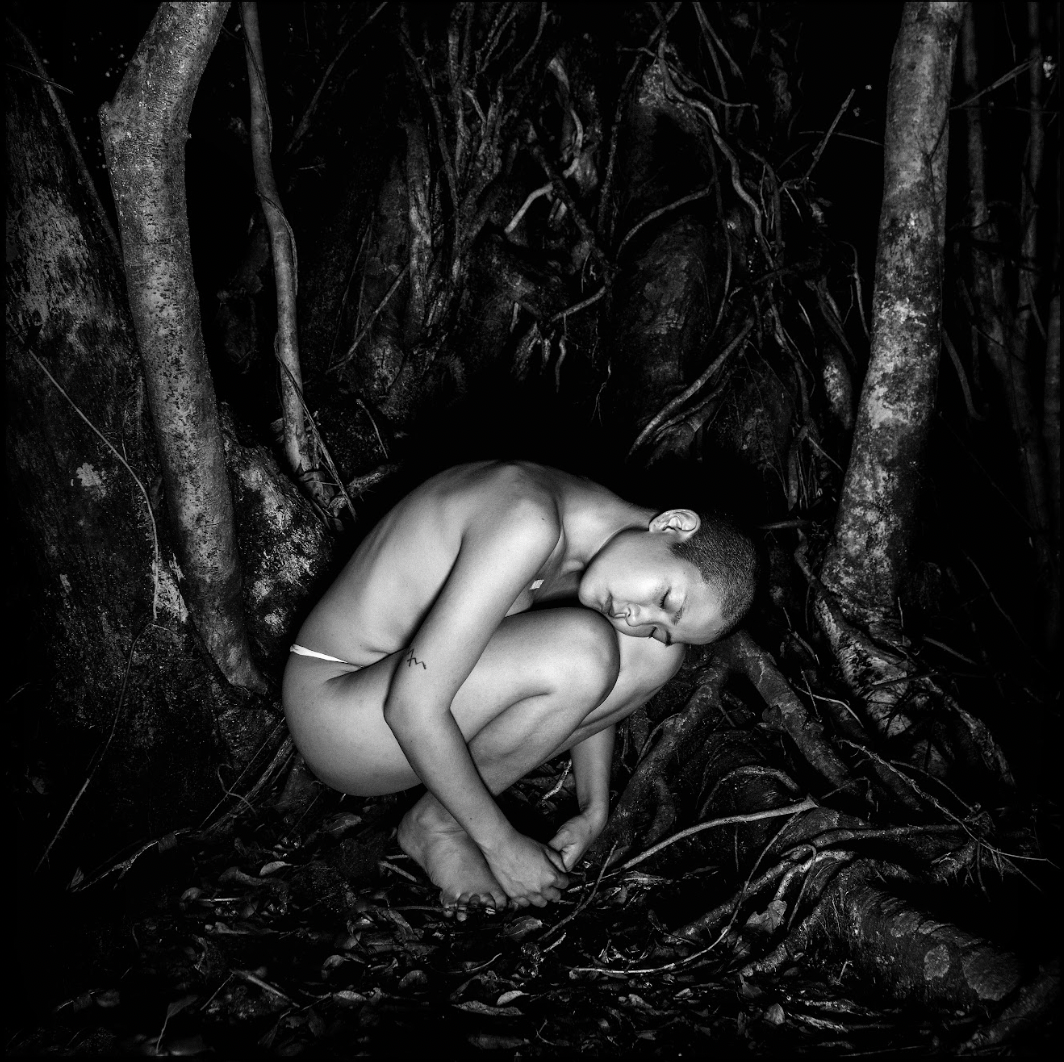

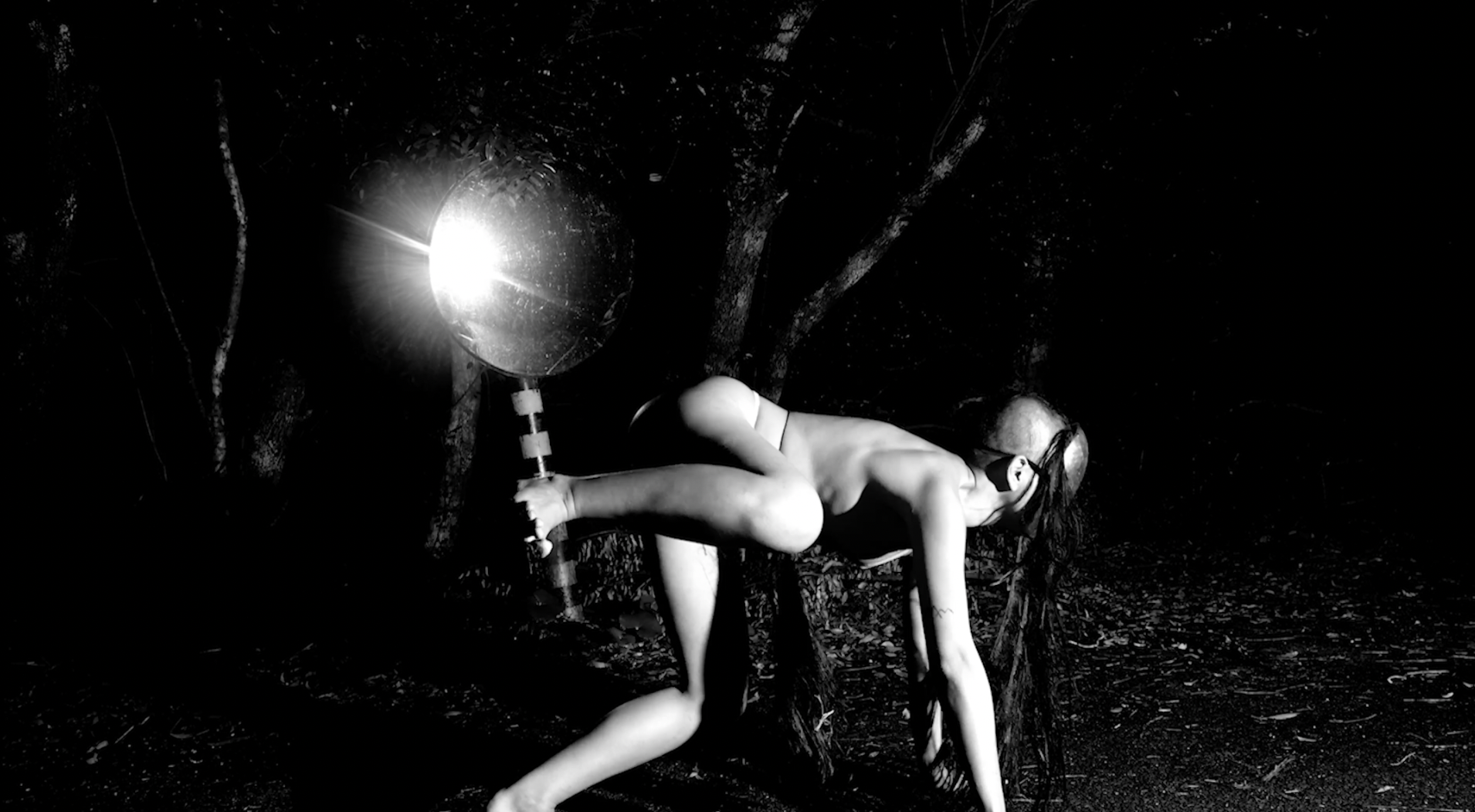

This time, I brought some materials for a vision I had of a character. I filmed footage for a new multi-media dance piece there – of a monster with a mirror searching rigorously for itself on the island, and eventually, being awe-struck by the beauty of the sunrise, where it finally relaxes. The monster’s body then transforms back into Amaterasu, the sun goddess. I resonated with Amaterasu’s story so deeply throughout my journey with cancer; where there is light, there is also shadow. We do not try to change the shadow. We also embrace it. For there is no light without shadow.

I was certainly still very much a mess mentally, emotionally, physically, and spiritually during my time there. It’s easier to reflect now that the space in-between is filled, and to be grateful for the spectrum of the year I had in the 間; how my crazy artistic practice saved my will to live on so many levels.

Maybe it really was drinking the unfiltered water directly from the mountain, or running and dancing around with my bare feet touching the earth for hours at a time – or simply just the time that passed sweating out the chemo drugs out of my body over the course of a few months – but my year did bookend with Yakushima and butoh, and I finally felt I returned to my body the following year.

In the midst of my running, I realized that I hadn’t been in a state of longing for a while. I hadn’t craved to be anywhere, do anything, write a single word, or make anything creative. I was grateful just to have the desire to create and to process the meaning later.

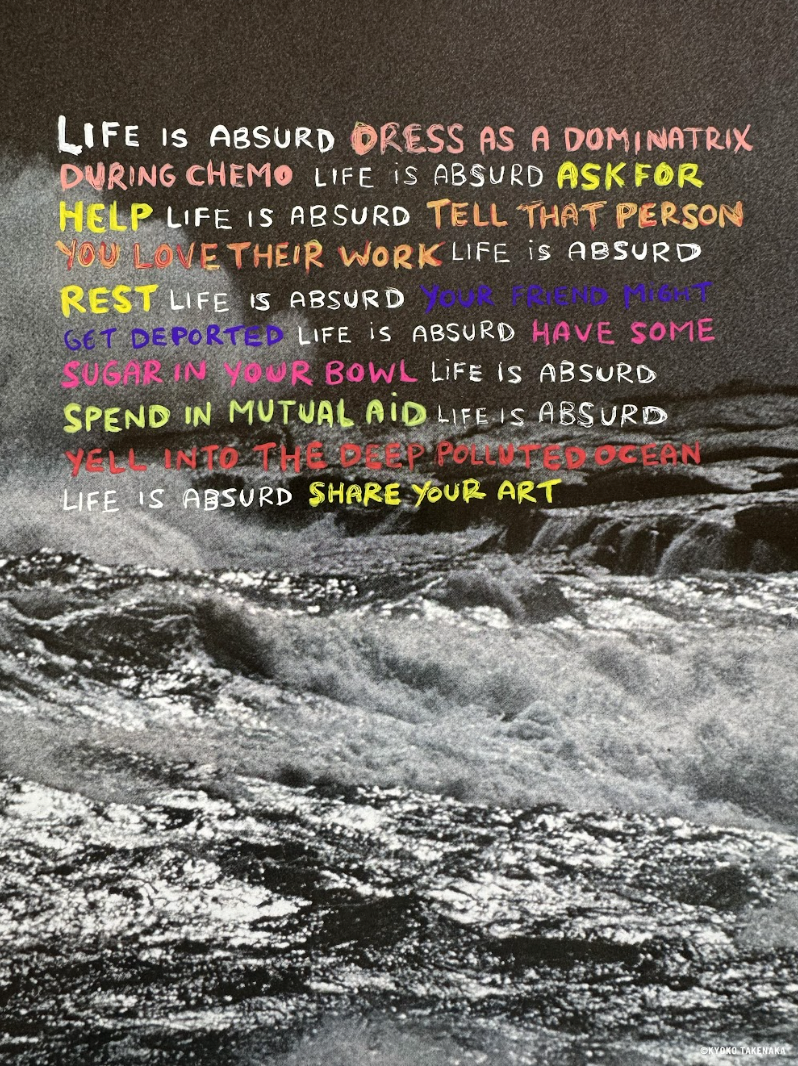

I am currently in remission and in better shape than I have been in many years. Now, whenever I get overwhelmed about planning a performance, a production, an audition, or being stubborn about picking up my favorite rice vinegar at the more inconvenient grocery store in the U.S., I simply repeat to myself: “Life is absurd,” before I do anything. Life is absurd, you had cancer. Life is absurd, make your art. Life is absurd, say no. Life is absurd, be gentle.

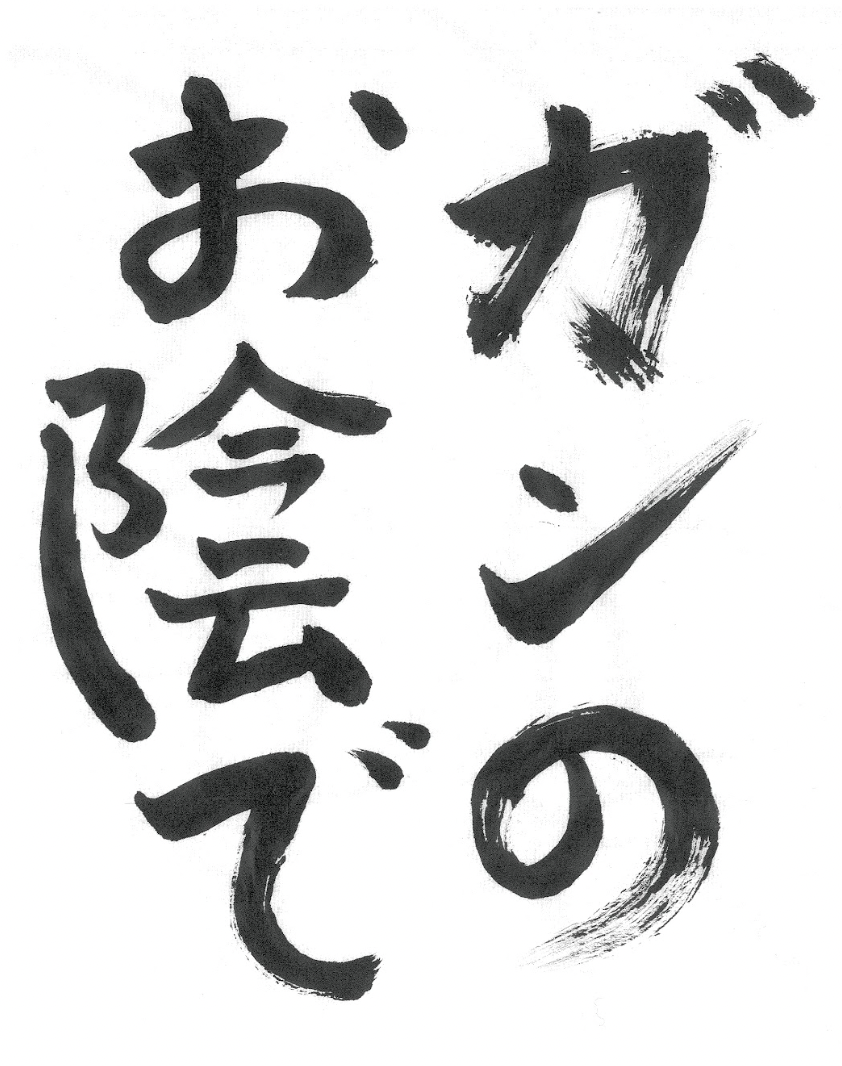

がんはひらがなで。(Cancer is spelled in hiragana).

意味は自分で。(the meaning is yours).

Usually in Japanese, most words can be spelled both in hiragana or katakana and kanji. The kanji characters provide context for the meaning behind the word, while hiragana or katakana is the word’s phonetic spelling. For example, you could spell the word for mountain as 山 (kanji; it literally looks like a mountain) 、やま (hiragana) 、or ヤマ (katakana).

What I find really interesting and grounding is that the word for cancer, ”がん”, is mostly spelled in hiragana or katakana even on official sources or newspapers. There are no kanji characters for it unless you are speaking of a certain type of cancer, which is the only time the kanji form is used.

I interpret that as – it just is. There is no meaning behind cancer. Or, there is no set reasoning conditioned to it. It is yours to make meaning out of, softly, like a mother explaining something to their child for the first time. A question like, “why is the sky blue?” You try to grasp onto a concept as you explain it, seeing which direction you will take as you improvise your way through. Will you give a scientific explanation, or tell the story of Seiryū, the blue dragon, or a Greek goddess, or just be honest and say, “I don’t know”?

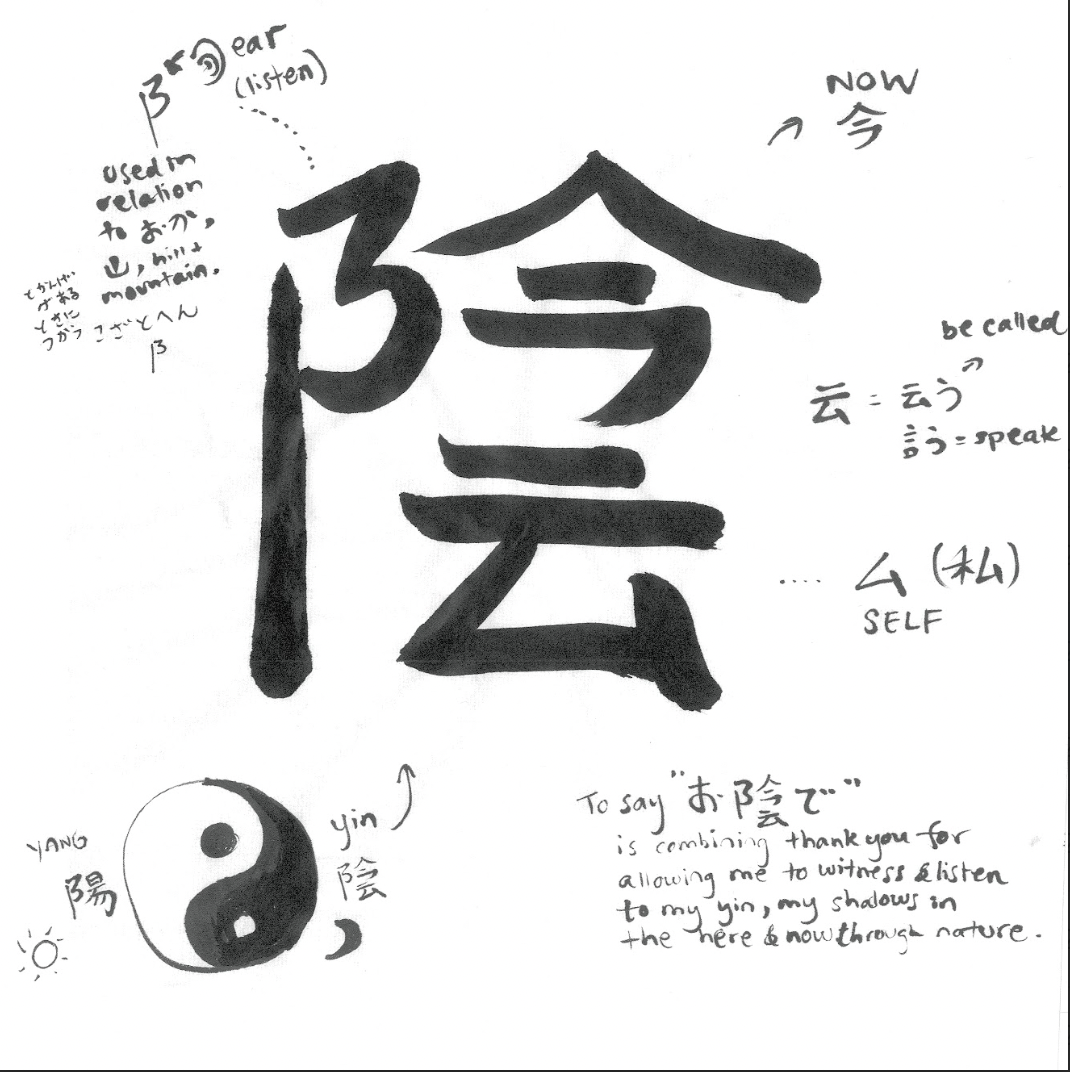

Okagesama (thanks to) is such an interesting phrase as well. Okage ”お陰” roughly translates to “thanks to”. For example, when you are thanking a mentor who introduced you to an opportunity, you would use this phrase, “okagesamade” (thanks to you).

For me, looking up the kanji characters helps me be present with what I’m actually saying or hearing. It was my friend Meibi in Yakushima who first told me, ”ガンのお陰で” (Thanks to cancer)… I live an aligned life, I get to live in Yakushima.” When she first said it, I couldn’t quite get on the same page just yet. I had just finished chemotherapy, and was still the most depressed I’ve ever been in my entire life. To be so close to death in my physical body and to come out the other side, and to get to live in my physical body thanks to so much community support means that I actually have to choose to live now. And I have to, get to, choose the life I want to live. That can feel daunting.

What’s interesting is that this kanji character “陰” for okage, or thanks to, is the same character as “yin” in yin and yang. Yin also means shadow. It is associated with, among other things, feeling (vs doing). My friend Stephanie told me that “yin always comes first, and yang comes second”. It’s better if we feel intuitively towards a direction, and then we take action. But for most of my time in treatment, I tried to refuse, and did the opposite; I took 10 flights in two months and just ran, ran, ran. Yakushima, many friends would tell me, is known as a yin island, and I certainly did just sit with so many of my feelings and let nature hold me unconditionally in my mess to teach me slowness and desire again.

If you break down the kanji character of the word Ma “間”, the character is made up of the radicals gate “門” and sun/day “日”. Maybe all I can ask for myself is the spaciousness to continue to explore – perhaps without having to put in words – what 「がん」or cancer has meant for me. That is the gift of my artistic practice, and something that deeply ties me to my desire. I can let the meaning reveal itself in small visual metaphors and movements, moment by moment. The only thing that is guaranteed is another sunrise each morning, and if we choose, our gratitude for it.

While preparing for a new performance, my butoh teacher told me last week, “Artists are always trying to make meaning out of performances before they do it. How boring. It is not up to you. That is up to the audience”.

I am still an artist grasping for correlation and meaning, but my butoh practice reminds me to keep exploring – relentlessly making space, making space, making space – and listening deeply to my yin, the yin that does not speak through words.